Biliary Tree

Primary imaging of the biliary tree depends increasingly on CT, ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging, and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and with diminishing reliance on invasive endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Multidetector CT (MDCT) with thin sections and multiplanar reformats can clearly demonstrate the normal anatomy, anatomic variants, stones, tumors, and inflammatory disease of the biliary system.

Anatomy

The bile ducts arise as biliary capillaries between hepatocytes. Bile capillaries coalesce to form intrahepatic bile ducts. Intrahepatic bile ducts branch in a predictable manner corresponding to the segments of the liver. Interlobular bile ducts combine to form two main trunks from the right and left lobes of the liver. The 3- to 4-cm-long common hepatic duct is formed in the porta hepatis by the junction of the main right and left bile ducts. The cystic duct runs posteriorly and inferiorly from the gallbladder neck to join the common hepatic duct and form the common bile duct (CBD). The 6- to 7-cm-long CBD courses ventral to the portal vein and to the right of the hepatic artery, descending from the porta hepatis along the free right border of the hepatoduodenal ligament to behind the duodenal bulb. Its distal third turns directly caudad, descending in the groove between the descending duodenum and the head of the pancreas just ventral to the inferior vena cava. The CBD tapers distally as it ends in the sphincter of Oddi, which protrudes into the duodenum as the ampulla of Vater. The CBD and the pancreatic duct share a common orifice in 60% of cases and have separate orifices in the remainder. In any case, they are in such close proximity that tumors of the ampullary region will generally obstruct both ducts.

Thin collimation (1–2.5-mm) MDCT with dynamic bolus intravenous contrast enhancement reveals normal intrahepatic ducts in about 40% of patients. Normal intrahepatic ducts are 2 mm in diameter in the central liver and taper progressively toward the periphery. The common hepatic duct is usually seen in the porta hepatis, and the CBD is routinely visualized descending adjacent to the descending duodenum. It is fair to use the generic term common duct to refer to both the common hepatic duct and the CBD because the cystic duct junction marking their anatomic partition is not routinely visualized on CT. The normal common duct does not exceed 6 mm in diameter in most adult patients. In elderly patients the normal common duct diameter increases by about 1 mm per decade (i.e., 7 mm is normal for patients in their 70s, and 8 mm is normal for those in their 80s). Contrast medium enhancement improves identification of both normal and dilated bile ducts by enhancing blood vessels and the surrounding parenchyma. Bile ducts are seen as lucent branching tubular structures. The bile ducts may be difficult to differentiate from blood vessels without contrast agent administration.

Technique

Evaluation for biliary obstruction is the most common reason to perform CT of the bile ducts. Water is preferred as an oral contrast agent in this clinical setting because high-density contrast in the duodenum may cause streaks and obscure stones in the adjacent CBD.

- •

The patient drinks 300 mL of water in 15 to 20 minutes just before CT examination.

- •

Thin sections (0.625–2.5 mm) with MDCT provide high-resolution images of the bile ducts.

- •

Multiphase imaging is commonly used. Stones may be seen best on noncontrast images. Scanning during the arterial phase demonstrates pancreatic lesions best. Delayed imaging at 15 to 20 minutes after intravenous contrast medium administration shows the delayed enhancement characteristic of cholangiocarcinomas.

- •

Isotropic voxel imaging allows high-resolution image reconstruction in multiple anatomic planes and in three dimensions.

Biliary Obstruction

CT is about 96% accurate in determining the presence of biliary obstruction, 90% accurate in determining its level, and 70% accurate in determining its cause. The major causes of biliary obstruction are gallstones, tumor, stricture, and pancreatitis ( Table 12.1 ). A rare but interesting cause of biliary obstruction is Mirizzi syndrome . A gallbladder stone impacted in the cystic duct induces cholangitis or erodes into the common duct to cause obstructive jaundice. Tumors include cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic head carcinoma, ampullary carcinoma, gallbladder carcinoma, and benign tumors of the bile duct such as biliary cystadenomas and granular cell tumors.

|

CT diagnosis of biliary obstruction depends on the demonstration of dilated bile ducts. The biliary tree dilates proximal to the point of obstruction, whereas bile ducts distal to the obstruction remain normal or are reduced in size. When cirrhosis, cholangitis, or periductal fibrosis prohibits dilation of the bile ducts in obstructive jaundice, the CT findings will be falsely negative. The CT findings of biliary obstruction include:

- •

multiple branching, round or oval, low-density tubular structures, representing dilated intrahepatic biliary ducts, coursing toward the porta hepatis. ( Figs. 12.1–12.3 );

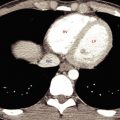

FIG. 12.1

Dilated bile ducts.

Postcontrast image showing dilated bile ducts (green arrowheads) in the liver as low-attenuation round and oval structures or as tortuous tubes. Note that in cross section the dilated bile duct (green arrow) is slightly larger in diameter than the adjacent portal vein (blue arrow) . The diameter of normal intrahepatic bile ducts should not be larger than 40% of the diameter of the adjacent portal vein.

FIG. 12.2

Dilated bile ducts.

(A) On noncontrast CT dilated bile ducts are difficult to recognize, appearing as ill-defined foci of low attenuation difficult to differentiate from unopacified blood vessels. (B) Following intravenous contrast agent administration the dilated low-attenuation bile ducts (green arrowheads) are much better defined and the enhanced now high-attenuation blood vessels (blue arrows) are now well seen.

FIG. 12.3

Dilated common duct.

Postcontrast coronal plane CT in a patient with pancreatic head carcinoma (not shown) reveals tortuous dilatation of the common bile duct (green arrow) in the porta hepatitis, as well as dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (red arrowhead) . The gallbladder (GB) , incompletely shown on this CT slice, was also dilated.

- •

dilatation of the common duct in the porta hepatis seen as a tubular or oval, fluid density tube greater than 7 mm in diameter;

- •

dilatation of the CBD in the pancreatic head seen as a round fluid density tube larger than 7 mm;

- •

enlargement of the gallbladder to more than 5 cm in diameter, when the obstruction is distal to the cystic duct.

Clues to the cause of biliary obstruction are illustrated in Fig. 12.4 .

- •

Abrupt termination of a dilated CBD is characteristic of a malignant process ( Fig. 12.5 ) even in the absence of a visible mass. Common tumors causing biliary obstruction include pancreatic head carcinoma, ampullary carcinoma, and cholangiocarcinoma. A small mass may be recognized at the point of biliary obstruction by careful inspection of noncontrast, arterial phase, portal venous phase, and delayed postcontrast CT images. Occasional benign biliary tumors may cause similar findings.

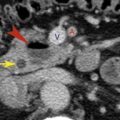

FIG. 12.5

Malignant tumor obstructing the common bile duct.

Magnified images from sequential slices of contrast-enhanced CT, proceeding from superior to inferior. (A) The common bile duct (red arrowhead) , in the head of the pancreas (P) , is mildly dilated to 10 mm. The nearby pancreatic duct (yellow arrow) is also dilated. (B) The common bile duct (red arrowhead) and the pancreatic duct (yellow arrow) become narrowed as they encounter the tumor in the head of the pancreas. (C) Both ducts disappear within the subtly defined tumor (curved red arrows) . Pathology confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A , Superior mesenteric artery; D , duodenum; V , superior mesenteric vein.

- •

Gradual tapering of a dilated duct is seen most commonly with benign disease such as inflammatory stricture or pancreatitis ( Fig. 12.6 ). Calcifications in the pancreas are a clue to the presence of chronic pancreatitis.

FIG. 12.6

Benign stricture of the common bile duct as a result of chronic pancreatitis.

Magnified sequential postcontrast CT images demonstrating progressive tapering of the distal common bile duct (red arrowheads) as it passes through the head of the pancreas. The pancreatic head is deformed, and multiple calcifications (curved yellow arrows) and cystic changes indicate chronic pancreatitis.

- •

The presence of choledocholithiasis ( Fig. 12.7 ) may be difficult to recognize because of the wide variation in the CT appearance of gallstones. Stones differ in CT attenuation from fat density to calcific.

FIG. 12.7

Stone in the common bile duct.

Magnified image of the distal common bile duct near the ampulla in a patient with biliary obstruction showing a gallstone (red arrowhead) as a slightly high-attenuation focus with the common bile duct. A thin rim of bile (green arrow) partially surrounds the obstructing stone. Ao , aorta; D , duodenum; IVC , inferior vena cava.

Choledocholithiasis

Stones in the biliary tree are a common cause of pancreatitis, jaundice, biliary colic, and cholangitis. However, stones in the bile ducts may also be asymptomatic. Most stones (95%) in the bile ducts form in the gallbladder although stones may also develop primarily within the bile ducts, especially when the gallbladder has been removed or is chronically obstructed. CT demonstrates approximately 75% of stones in the CBD.

- •

Gallstones in the bile ducts are seen as calcific (calcium bilirubinate stones), soft-tissue (mixed stones), or fat (cholesterol stones) density structures. Stones may be isodense with bile and not visualized by CT (15%–25% of gallstones). Stones may also contain nitrogen gas and show foci of air attenuation.

- •

The stone may appear as a central density surrounded by a rim or crescent of lower-density bile—the target or crescent sign ( Fig. 12.7 ).

- •

Low-attenuation stones may be defined by a higher-attenuation outer rim, called the rim sign.

- •

Abrupt termination of the CBD proximal to the ampulla is suggestive of a stone in the CBD.

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma is a slow-growing adenocarcinoma arising from the epithelium of the bile ducts. It may occur as a complication of choledochal cyst, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), Caroli disease, intrahepatic stone disease, or clonorchiasis. Prognosis is poor, with recurrence rates of 60% to 90% after surgical resection. The growth patterns of cholangiocarcinoma are mass-forming intrahepatic (see Fig. 11.27 ), periductal infiltrating, and intraductal growing. Tumors occur in the periphery of the liver (10%), in the hilum (25%), or in the extrahepatic bile ducts (65%). The tumors are hypovascular and markedly fibrotic, resulting in poor contrast enhancement and limited CT detection especially on early postcontrast scans. Delayed scans at 10 to 20 minutes after contrast medium injection are recommended for optimal tumor detection.

- •

Intrahepatic mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma appears as a homogeneous tumor with irregular borders and remarkably low attenuation. The mass is highly fibrotic and often shows only weak peripheral enhancement on early postcontrast images (see Fig. 11.27 ). Delayed images (up to several hours) may show central or diffuse enhancement. Bile ducts peripheral to the tumor are often obstructed and dilated.

- •

Periductal-infiltrating lesions grow along the bile ducts in an elongated, branching pattern. Irregular narrowing of the duct produces obstruction. Tumor-involved ducts are narrowed with thick walls, whereas peripheral ducts are dilated with thin walls. Visible tumor mass is minimal. Cholangiocarcinomas occurring at the confluence of the right and left hepatic bile ducts are frequently small and infiltrating, causing early biliary obstruction ( Fig. 12.8 ). These have been termed Klatskin tumor.