and Arumugam Rajesh2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

(2)

Department of Radiology, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Tr Leicester General Hospital, Leicester, UK

Case 4.1

Brief Case Summary:

Case 1: 16 year old male with umbilical discharge

Case 2: Newborn male with midline mass

Case 3: 63 year old male with hematuria

Case 4: 44 year female with pelvic pain

Imaging Findings

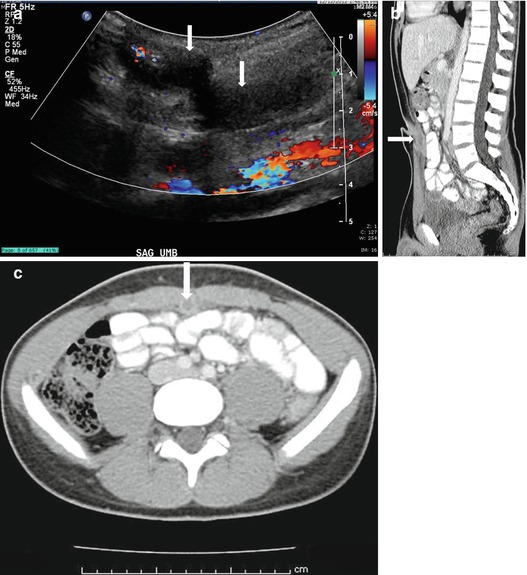

Case 1: Sagittal transabdominal ultrasound image of the abdomen demonstrates a bilobed hypoechoic mass extending through the anterior abdominal wall, without detectable vascularity (Fig. 4.1a). Sagittal (Fig. 4.1b) and axial (Fig. 4.1c) images from a CT scan of the abdomen performed with intravenous and oral contrast demonstrate a sinus tract extending through the anterior abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus (arrows, Fig. 4.1b, c).

Fig. 4.1

Case 1. (a) Sagittal transabdominal ultrasound image of the abdomen demonstrates a bilobed hypoechoic mass extending through the anterior abdominal wall, without detectable vascularity. (b) Sagittal and (c) axial images from a CT scan of the abdomen performed with intravenous and oral contrast demonstrate a sinus tract extending through the anterior abdominal wall at the level of the umbilicus (arrows, b, c)

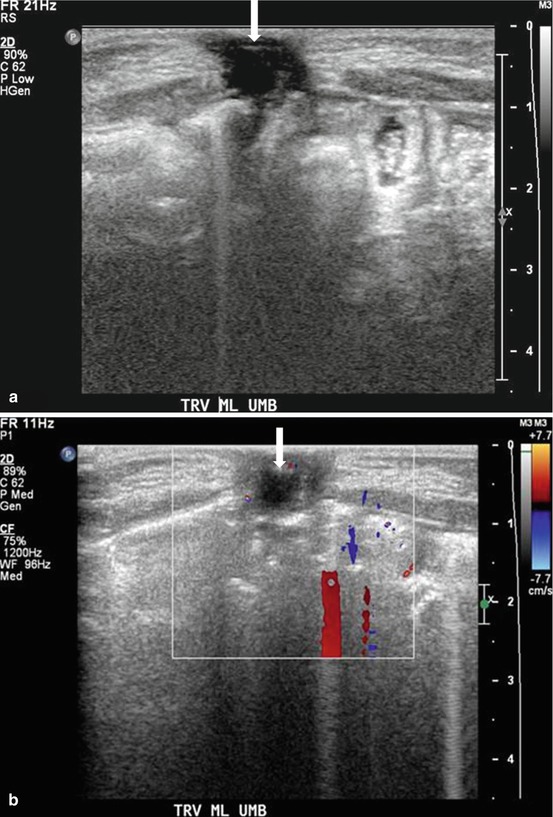

Case 2: Transverse gray scale (Fig. 4.2a) and color Doppler (Fig. 4.2b) images at the level of the palpable abnormality demonstrate the presence of a hypoechoic midline mass in the region of the umbilicus without internal vascularity.

Fig. 4.2

Case 2. (a) Transverse gray scale and (b) color Doppler images at the level of the palpable abnormality demonstrate the presence of a hypoechoic midline mass (arrow) in the region of the umbilicus without internal vascularity

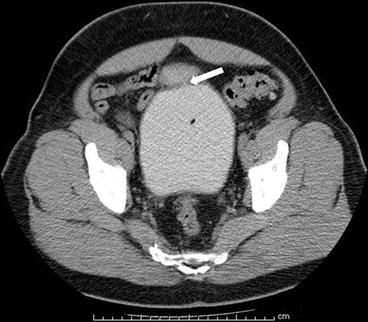

Case 3: Axial image from a CT scan of the pelvis (Fig. 4.3) performed in the excretory phase demonstrates the presence of a focal contained collection of contrast connected to the anterior bladder wall via a thin stalk.

Fig. 4.3

Case 3. Axial image from a CT scan of the pelvis performed in the excretory phase demonstrates the presence of a focal contained collection of contrast connected to the anterior bladder wall via a thin stalk (arrow)

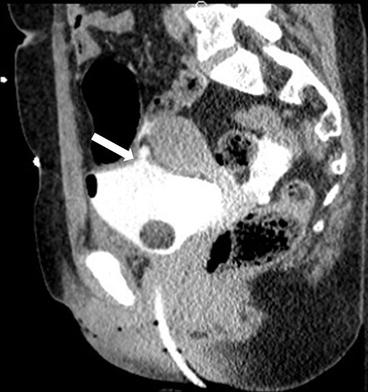

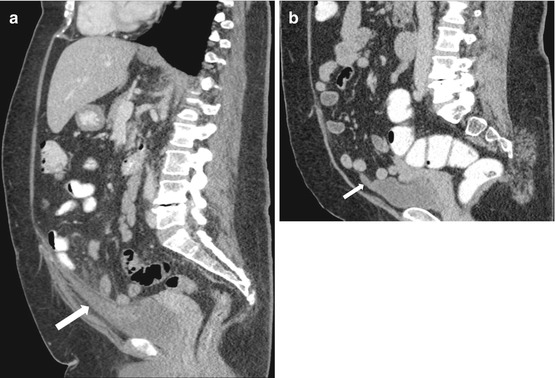

Case 4: Sagittal image from a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed with intravenous and oral contrast demonstrates the presence of an inflammatory tubular mass which is contiguous with the anterior and superior aspects of the bladder (arrow, Fig. 4.4a). Sagittal image from a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed 3 years earlier demonstrates a tubular hypoattenuating mass in the same location (arrow, Fig. 4.4b).

Fig. 4.4

Case 4. (a) Sagittal image from a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed with intravenous and oral contrast demonstrates the presence of an inflammatory tubular lesion which is contiguous with the anterior and superior aspects of the bladder (arrow). (b) Sagittal image from a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed 3 years earlier demonstrates a tubular hypoattenuating lesion in the same location (arrow)

Differential Diagnosis

Congenital urachal abnormalities (urachal sinus, urachal cyst, urachal diverticulum, patent urachus).

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Case 1: Umbilical–urachal sinus

Case 2: Urachal cyst

Case 3: Urachal diverticulum

Case 4: Urachal diverticulitis

The urachus is a midline tubular structure which connects the bladder apex to the umbilicus. It is derived in part from the allantois (an outpouching near the base of the yolk sac) as well as the ventral aspect of the cloaca. During fetal development, the urachus undergoes progressive obliteration, such that it exists as a non-functioning fibrous band at the time of birth (also known as the median umbilical ligament). It is located in an extraperitoneal location, posterior to the transversalis fascia and anterior to the parietal peritoneum.

Congenital abnormalities of the urachus arise from failure of appropriate obliteration. Four discrete categories are recognized, and are as follows:

1.

Patent urachus (50 %): the tract remains patent from the bladder apex to the umbilicus.

2.

Umbilical-urachal sinus (approximately 15 %): the tract remains open at the umbilical end.

3.

Urachal diverticulum (approximately 3–5 %): the tract remains open at the bladder apex.

4.

Urachal cyst (approximately 30 %): The tract closes at the umbilical end and at the bladder apex, leaving a midline cystic structure.

The patent urachal variant is most symptomatic, often presenting as persistent urine discharge from the umbilicus after birth. Furthermore, patients with a patent urachus often have other genitourinary tract abnormalities, with posterior urethral valves or urethral atresia found in up to one third of cases. The remaining variants are often asymptomatic unless complicated by infection.

Findings can be seen on ultrasonography, particularly in the pediatric population, or may be incidental seen on CT or MRI. The presence of a midline hypoechoic mass, either isolated as in a urachal cyst, associated with the umbilicus as seen in a urachal sinus, or associated with the bladder as seen in a urachal diverticulum, is often seen. Superimposed infection may be suspected with the presence of thick, irregular walls and multiple low level internal echoes. Cross-sectional imaging demonstrates the presence of a midline fluid-attenuating mass, although the presence of hemorrhage or infection may give density values higher than simple fluid alone. The presence of a thick, irregularly enhancing rim with adjacent fat stranding suggests the presence of infection.

Incidentally discovered congenital urachal lesions in adults usually require no further treatment. Surgical excision should be considered for incidentally discovered lesions in the pediatric population given the potential risk of malignant transformation. Infected congenital urachal remnants require antibiotics with or without drainage, followed by consideration of resection, particularly in the pediatric population.

Pitfalls

Patent urachus, umbilical-urachal sinus and urachal diverticula usually pose no diagnostic dilemma as a combination of ultrasound and CT or MR is sufficient for a definitive diagnosis. Urachal cysts can look similar to other benign entities such as a mesenteric cyst. An isolated cystic peritoneal metastasis from a mucinous primary may potentially have a similar appearance, although the presence of additional lesions and ascites is almost always present.

Teaching Points

1.

The urachus connect the bladder apex to the umbilicus. It normally obliterates at the time of the birth and remains as an extra peritoneal fibrous structure called the median umbilical ligament.

2.

Congenital urachal abnormalities result from a failure of this involution. Four categories exist: patent urachus, umbilical-urachal sinus, urachal diverticulum, and urachal cyst. These are most commonly asymptomatic with the exception of a patent urachus which may present with umbilical discharge.

3.

Infected lesions require antibiotic with possible drainage. Incidental lesions in adults require no treatment, while most lesions regardless of symptoms in the pediatric population are excised due to the risk of potential malignant transformation.

Case 4.2

Brief Case Summary

76 year old female with abdominal pain and fever

Imaging Findings

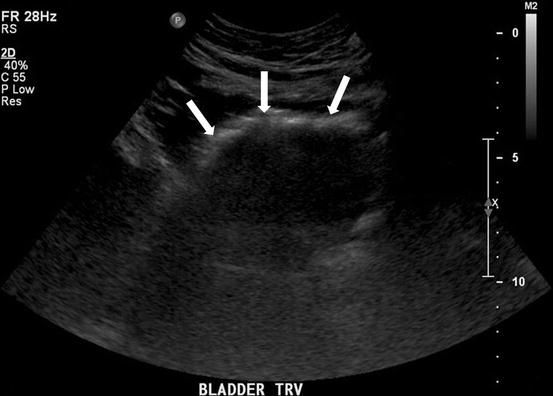

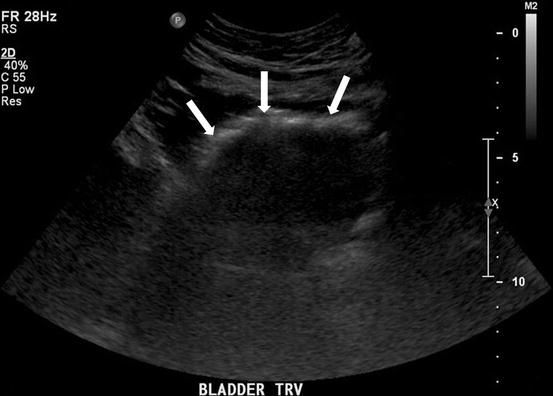

Plain radiograph of the abdomen demonstrates multiple lucencies in the mid pelvis (Fig. 4.5). A transverse gray scale US image demonstrates the presence of an abnormal curvilinear region of increased echogenicity over the anterior aspect of the bladder with the presence of posterior “dirty” shadowing (Fig. 4.6). Axial CT image (Fig. 4.7) at the level of the pelvis on lung windows demonstrates the presence of abnormal lucency’s in the bladder wall (Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.5

Plain radiograph of the abdomen demonstrates multiple lucencies in the mid pelvis (arrow)

Fig. 4.6

A transverse gray scale US image demonstrates the presence of an abnormal curvilinear region of increased echogenicity (arrows) over the anterior aspect of the bladder with the presence of posterior “dirty” shadowing

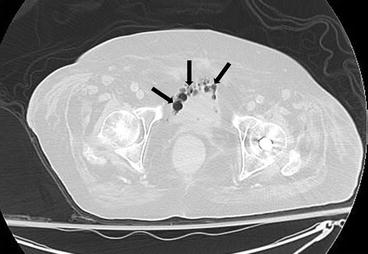

Fig. 4.7

Axial CT image at the level of the pelvis on lung windows demonstrates the presence of abnormal lucency’s (arrows) in the bladder wall

Differential Diagnosis:

Emphysematous cystitis, recent Foley catheterization/cystoscopy, colovesicular or enterovesicular fistula.

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Emphysematous cystitis.

Emphysematous cystitis (EC) is a rare complicated form of cystitis, characterized by the presence of air within the bladder wall and lumen. Risk factors for developing EC include the presence of diabetes, history of recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI) and conditions that promote urinary stasis such as neurogenic bladder or bladder outlet obstruction. Elderly diabetic females are the most commonly afflicted patient demographic. A variety of both bacterial and fungal organisms have been implicated, with Escherichia coli, Enterobacter aerogenes and Klebsiella pneumonia among the most commonly cultured organisms. The exact pathogenesis is debated but is likely related to fermentation of urinary glucose or albumin by organisms leading to the production of carbon dioxide bubbles that subsequently accumulate in the bladder lumen or wall. Clinical symptoms are typically indistinguishable from an uncomplicated UTI with patients complaining of dysuria or increased urinary frequency. Occasionally patients may be asymptomatic or present with pneumaturia.

Imaging can readily diagnosis EC and EC is often diagnosed on imaging. Conventional radiography demonstrates the presence of curvilinear lucency’s in the lower midline pelvis, corresponding to the bladder wall. Bubbles of gas may also be seen within the bladder lumen itself. These findings can be confirmed sonographically where collections of intramural air are seen as curvilinear regions of increased echogenicity associated with posterior “dirty” shadowing. Further imaging with a CT examination is useful to confirm the diagnosis, as well as look for any signs of upper tract involvement, which typically require more aggressive treatment. Furthermore, CT can typically exclude other causes/mimickers of air in this location such as a colovesicular fistula or an underlying abscess.

Treatment is conservative and includes a combination of bladder drainage and antibiotics with appropriate control of comorbid conditions. Surgical options are reserved for patients who fail conservative therapy. Overall mortality rates are approximately 7 % in contrast to emphysematous pyelonephritis, where mortality rates have been reported up to 50 %.

Pitfalls

Colovesicular or enterovesicular fistulas can mimic emphysematous cystitis though this distinction is usually apparent on cross-sectional imaging. A history of Crohn’s disease, diverticulitis, or radiation treatment is associated with the formation of colovesicular fistulas. Foley catherization and/or recent cystoscopy can result in residual amounts of air typically isolated to the bladder lumen

Teaching Points

1.

Emphysematous cystitis is a form of complicated UTI characterized by air in the bladder wall and lumen, most often seen in elderly diabetic females.

2.

Treatment requires bladder drainage and antibiotics. Surgical intervention is rare, and reserved for failure of conservative management or severe infections.

3.

Cross-sectional imaging should be used to detect upper tract disease which requires more aggressive treatment and is associated with a higher morbidity and to look for mimickers of EC such as colovesicular fistula.

Case 4.3

Brief Case Summary:

40 year old man, an immigrant from sub-saharan country who presented with dysurea.

Imaging Findings:

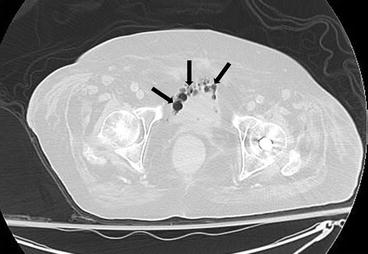

Axial CT image through the bladder (Fig. 4.8) shows curvilinear calcifications in the bladder wall. On a more caudal axial CT image (Fig. 4.9), calcifications are also seen involving the right ureter.

Fig. 4.8

Axial CT image through the bladder shows curvilinear calcifications (arrows) in the bladder wall

Fig. 4.9

On a more caudal axial CT image, calcifications are also seen involving the right ureter (arrow)

Differential Diagnosis

Tuberculosis, primary carcinoma, radiation/cyclophospahamide cystitis, amyloidosis.

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Bladder schistosomiasis

Genitourinary schistosomiasis is caused by Schistosoma hematobium, a parasitic fluke that is endemic in parts of Africa. Transmission is through contaminated water wherein the larvae penetrate human skin, pass through the lymphatic system, lungs, and liver at which time the larvae travel to the portal vein. After maturation, the worms travel to the pelvic veins and deposit eggs on the bladder wall inciting a granulomatous reaction causing cystitis. Calcification of these dead eggs causes the typical bladder and ureteral wall calcifications.

The clinical features depend on the stage of the disease ranging from dermatitis at the time of larvae penetration to urinary symptoms like dysuria, suprapubic pain, hematuria and local perineal lesions in later stages. Diagnosis is made by microscopic examination of urine.

Urinary bladder and lower ureters are the most commonly affected organs. Later stages of the disease may also show involvement of entire genitourinary system.

Earliest change is persistent ureteric filling on IVP followed by distal ureteric dilatation due to lack of peristalsis. Strictures with fibrosis and calcification are seen in later stages. The ureteric calcifications are fine initially followed by coalesced areas showing a circular pattern on axial CT and as linear parallel lines on X ray. Ureteritis cystica represents as bubble-like filling defects due to deposition of ova in ureteral walls and may be seen in children.

Bladder changes comprise of wall thickening, haziness initially followed by calcification, fibrosis and contraction with reduced capacity. The calcifications are more common in younger patients and can be varied in distribution. They may involve one side or both, the trigone or bladder base, and can be fine, granular, or thick and irregular. The imaging findings correlate to the pathologic course of disease with nodular wall thickening in the acute phase which progresses to a fibrotic, thick-walled bladder with calcifications in the chronic phase. Bladder decalcification is possible if there is resorption or excretion of the deposited eggs.

A syndrome called bladder neck obstruction can be seen where the eggs are deposited predominantly in the bladder trigone resulting in muscle hypertrophy followed by fibrosis and atrophy leaving elevated mucosa. This protrudes into the bladder lumen mimicking a mass like lesion causing obstruction of the bladder neck.

In children, mucosal inflammation may also cause formation of bud like masses in lamina propria which in turn may differentiate and result in cystitis cystica and cystitis glandularis.

Schistosomiasis is a strong predisposing factor for development of squamous cell carcinoma in endemic areas. It may present as a sessile focal mass or focal wall thickening arising from the trigone or lateral walls. Extravesical spread is common and carries a poor prognosis.

Pitfalls

Tuberculosis affecting the urinary bladder results in a small capacity bladder with wall calcification, which can be easily differentiated from schistosomiasis where the bladder usually has a normal capacity until late chronic stages as the calcifications are submucosal. Tuberculosis generally affects the kidneys first unlike schistosomiasis which primarily affects the ureter and bladder.

Causes of bladder calcification other than schistosomiasis generally produce focal nodular calcific areas.

Teaching Points

1.

Bladder and ureters are the main organs affected by the parasite schistosomiasis. The kidneys are affected only in late stage of the disease

2.

Curvilinear bladder wall calcifications is the classic imaging feature of bladder schistosomiasis which is best delineated on noncontrast enhanced CT where ureteral involvement can also be assessed.

3.

Chronic infection with schistosomiasis is a strong predisposing factor of squamous cell carcinoma.

Case 4.4

Brief Case Summary:

Case 1 41 year old female pedestrian hit by car

Case 2 57 year old female with gross hematuria following instrumentation of urinary tract.

Imaging Findings:

Sagittal (Fig. 4.10) and axial (Fig. 4.11) images from a CT cystogram demonstrates a focal bladder defect at the bladder dome with extravasation of contrast between loops of bowel. In another patient, axial (Fig. 4.12) and coronal (Fig. 4.13) images from a CT cystogram shows a focal defect in the right lateral bladder wall and extra vesicular contrast is visualized in the space of Retzius consistent with an extraperitoneal bladder rupture. Of note, both patients have a Foley catheter through which contrast was instilled for the CT cystogram.