Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

- ◼

Most of the small and large bowels originate from the midgut, except the proximal duodenum (up to the ampulla of Vater), which originates from the foregut, and the portion of the colon distal to the proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon, which originates from the hindgut.

- ◼

The blood supply follows the same distribution, where the bowel arising from the midgut receives most of its blood supply from the superior mesenteric artery, the portion arising from the foregut from the celiac artery and that arising from the hindgut mainly from the inferior mesenteric artery, with rich anastomosis between these arterial branches.

- ◼

Normal intestinal wall thickness depends on the degree of bowel distention and the imaging modality. The normal jejunum wall thickness measures approximately 2 mm and the ileum 1 mm on enteroclysis. On computed tomography (CT), 3 mm for the small bowel and 5 mm for the large bowel are accepted as the upper limit of normal when the bowel is completely distended.

- ◼

When considering the imaging findings that help narrow the differential diagnosis of a pathological bowel inflammatory condition, several factors are important. These include the length of involvement, location of involvement, degree of thickening, and extraintestinal manifestations of the disease. By carefully considering these anatomic considerations, the differential diagnosis can be considerably narrowed.

General considerations

Because the clinical manifestations of patients with bowel wall thickening are broad and overlap with other pathologies, a patterned approach using several key observations can help narrow the differential diagnosis.

Length of involvement

The length of thickened bowel is important in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Certain entities tend to be focal, segmental, or diffuse.

Focal disease (2–10 cm)

- ◼

Neoplasm.

- ◼

Diverticulitis.

- ◼

Infection (tuberculosis/amebiasis).

Segmental disease (10–40 cm)

- ◼

Crohn disease.

- ◼

Ischemia.

- ◼

Infection.

- ◼

Ulcerative colitis (typically begins in the rectum and spreads proximally).

- ◼

Rarely neoplasm (especially lymphoma).

Diffuse disease

- ◼

Usually benign.

- ◼

Infection.

- ◼

Ulcerative colitis (can affect the entire colon).

- ◼

Vasculitis (can affect long bowel segment, small bowel involvement is more common).

Location of involvement

Whereas most pathological conditions can affect any area of the bowel, some pathological entities have a propensity to localize to certain areas.

Cecal region

- ◼

Amebiasis.

- ◼

Typhlitis (neutropenic colitis).

- ◼

Tuberculosis.

Isolated splenic flexure and proximal descending colon

- ◼

Watershed area for low-flow intestinal ischemia.

Rectum

- ◼

Early stages of ulcerative colitis.

- ◼

Stercoral colitis.

Multiple skip regions

- ◼

Crohn disease.

Degree of thickening

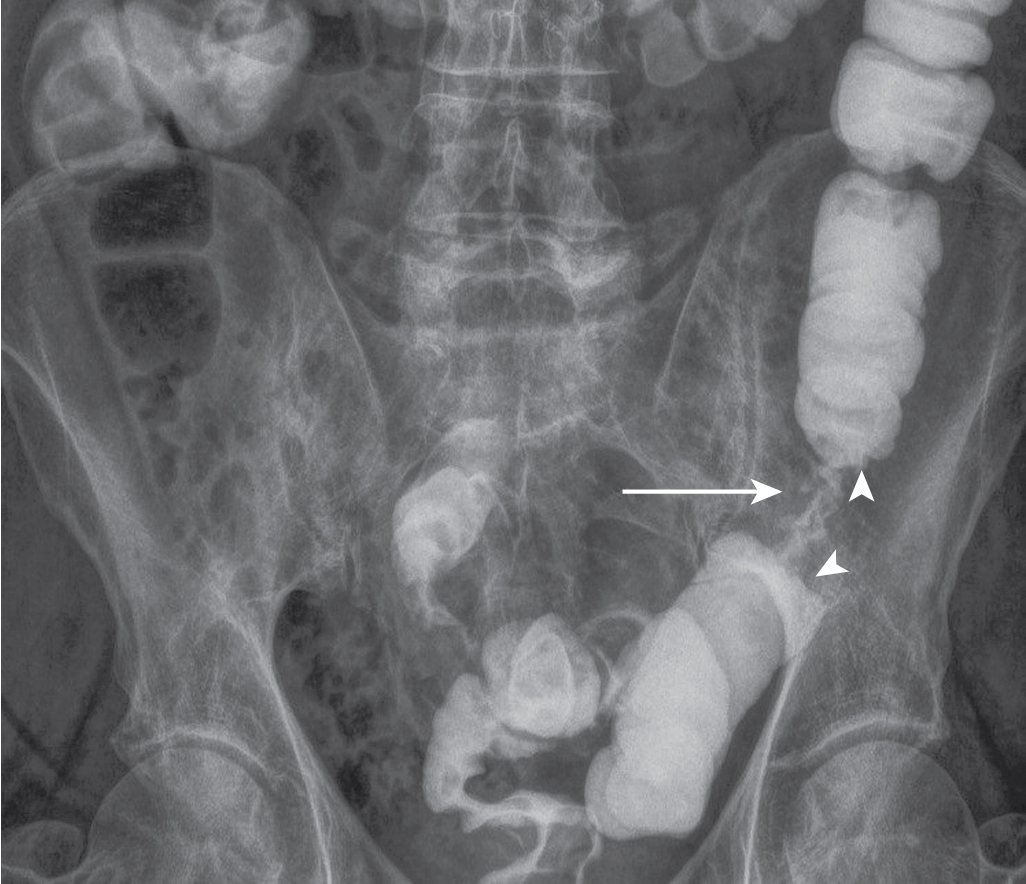

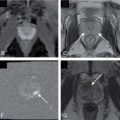

There is significant overlap in the degree of bowel wall thickening among different pathological processes. Mild thickening may be seen in mild inflammation. Marked bowel wall thickening may be seen in pseudomembranous, tuberculous, and cytomegaloviral colitis, as well as bowel neoplasms and vasculitis. Occasionally, the degree of thickening and the imaging appearance of bowel malignancy and inflammation may overlap, for example, the appearance of colon cancer and diverticulitis ( Fig. 6.1 ). In both cases, the disease is focal or involves a short segment of colon and may be associated with marked thickening of the bowel wall. Inflammatory changes in the mesentery have been shown to favor inflammation, and adjacent lymphadenopathy has been shown to favor colon cancer.

Pattern of enhancement

The pattern of enhancement can be important in discriminating different forms of intestinal pathology.

White enhancement

When the thickened bowel enhances avidly.

- ◼

Acute infection and inflammatory bowel disease.

Water halo sign

Edema of the submucosa and hyperenhancement of the mucosa and serosa.

- ◼

Acute infection, active inflammation, shock bowel.

Fat halo sign

Fat infiltration of the submucosa.

- ◼

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

- ◼

Normal variant (obesity or steroid usage).

Gray enhancement (diminished enhancement)

- ◼

Ischemia.

Heterogeneous

- ◼

Neoplasm typically.

Extraintestinal manifestations

When an abnormal segment of bowel is evaluated, the adjacent mesentery, presence and attenuation of abdominal lymph nodes, and status of the vasculature must be assessed.

Abnormalities pertaining to these structures can be helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Low-attenuating lymph nodes are often associated with tuberculosis or Whipple disease. Mesenteric changes including fibrofatty proliferation, sinus formation, and hyperemia in the vessels subtending an abnormal segment suggest Crohn disease. Filling defects in the vessels suggest colonic ischemia.

Techniques and specific disease processes

Radiography

Plain radiographs of the abdomen are obtained in patients with acute presentation to rule out bowel obstruction or perforation. Plain radiographic findings are often normal or nonspecific. Barium studies are rarely indicated for acute disease.

Plain films are helpful in demonstrating bowel obstruction as seen in cases of small or large bowel adenocarcinoma. Barium studies can demonstrate a wide spectrum of findings from “apple core” lesions seen in primary bowel adenocarcinoma ( Fig. 6.2 ), to a more infiltrative process leading to a malignant stricture subsequently causing bowel obstruction.