Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

- ◼

There are three major anatomic regions that may contribute to right lower quadrant pain. Organ systems with differential diagnoses include:

- ◼

Gastrointestinal system: cecum, ascending colon, appendix.

- ◼

Acute appendicitis.

- ◼

Acute cecal diverticulitis.

- ◼

Inflammatory bowel disease.

- ◼

Bowel obstruction, ileus.

- ◼

Mesenteric lymphadenitis.

- ◼

Meckel diverticulum.

- ◼

- ◼

Genitourinary/gynecological system: right ovary, right fallopian tube.

- ◼

Tuboovarian abscess.

- ◼

Ovarian cyst or tumor.

- ◼

Ovarian torsion.

- ◼

Ectopic pregnancy.

- ◼

Fibroids.

- ◼

- ◼

Musculoskeletal system: right lower ribs, right anterolateral abdominal wall muscles.

- ◼

Radicular symptoms (disk prolapse/protrusion).

- ◼

Sacroiliitis.

- ◼

Herpes zoster.

- ◼

Abdominal wall or iliopsoas abscess/hematoma.

- ◼

Retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

- ◼

- ◼

Techniques

- ◼

Abdominal ultrasound has limited performance characteristics for adults with right lower quadrant pain. However, in children and pregnant females, ultrasound is the initial imaging modality of choice, especially if appendicitis is suspected as the cause of right lower quadrant pain.

- ◼

If a pelvic etiology is suspected as the cause of right lower quadrant pain in a female, pelvic ultrasound is the initial imaging modality of choice.

- ◼

According to the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria, computed tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast is the primary diagnostic imaging modality of choice for the evaluation of patients with right lower quadrant pain because of its high diagnostic yield and early diagnosis of complications like perforation of the appendix.

- ◼

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast is the next imaging modality of choice in pregnant females if ultrasound is nondiagnostic.

Protocols

Computed tomography

- ◼

Oral contrast is generally not administered in emergency settings because of time delay, inability of patients to ingest large volumes of fluid, and potential need for emergency surgery. Lack of oral contrast may be a disadvantage in patients with paucity of intraabdominal fat, limiting detection of the appendix and subtle inflammatory changes in the right lower quadrant. Identification of bowel wall thickening and luminal narrowing is also limited without enteric contrast.

- ◼

Rectal contrast is also used at some institutions for right lower quadrant pain if appendicitis is the suspected etiology.

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

T2-weighted sequences are the most important sequence for visualization of a fluid filled appendix, adjacent free fluid, and inflammation.

Specific disease processes

Gastrointestinal system

Acute appendicitis

- ◼

Appendicitis is the most frequent cause of acute abdominal pain requiring surgical intervention and is the most common emergent abdominal operation performed in the United States.

Ultrasound

- ◼

In the younger population, ultrasonography may be used as an initial imaging evaluation to avoid ionizing radiation.

- ◼

The typical ultrasound findings of appendicitis include visualization of a noncompressible, blind-ending tubular structure that is distended with fluid and measures more than 6 mm in diameter during graded compression.

- ◼

Appendicoliths may be visualized as echogenic, shadowing foci within the lumen of the appendix ( Fig. 11.1 ).

Fig. 11.1

Appendicolith. The distended, blind-ending appendix contains an intraluminal echogenic focus at the tip (measured with calipers), with some associated acoustic shadowing, consistent with an appendicolith.

Computed tomography

- ◼

Enlarged and distended appendix, with surrounding inflammatory changes, fascial thickening, and small amounts of free intraperitoneal fluid ( Fig. 11.2 ).

Fig. 11.2

Axial computed tomography scan of the pelvis showing a dilated, fluid-filled, inflamed appendix with an intraluminal appendicolith.

- ◼

Arrowhead sign: edema at the origin of the appendix with thickening of the adjacent cecum.

- ◼

There is a wide variation in the diameter of the appendix in normal patients, with sizes ranging up to 1 cm. However, mean values range between 5 and 7 mm depending on whether the appendix is distended with air. Therefore when the appendix measures slightly greater than the standard cutoff value of 6 mm, secondary signs of inflammation should be sought to determine whether appendicitis is present.

- ◼

Filling of the appendix by orally or rectally introduced positive contrast material is a useful imaging finding in excluding obstruction of the appendix and, therefore, acute appendicitis.

- ◼

The most important complication of acute appendicitis that should be recognized with CT is focal appendiceal rupture. Signs of rupture include periappendiceal abscess, extraluminal gas (localized or free), free peritoneal fluid, and focal poor enhancement of the appendiceal wall ( Fig. 11.3 ).

Fig. 11.3

Computed tomography scan after oral and intravenous administration of contrast shows acute appendicitis with perforation. The lateral wall of the dilated, inflamed appendix is interrupted, and there is extraluminal gas and fluid, representing the periappendiceal abscess.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

MRI is frequently used to evaluate for suspected appendicitis in pregnant patients ( Fig. 11.4 ).

Fig. 11.4

Acute appendicitis in pregnancy. A, Coronal fat-suppressed T2-weighted image showing a thick-walled appendix with periappendical inflammation ( arrows ) in this pregnant patient. B, Axial diffusion-weighted image demonstrates intramural edema within the inflamed appendix ( arrows ).

(From Roth C, Deshmukh S. Fundamentals of Body MRI , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.)

- ◼

MRI offers high diagnostic accuracy and is an excellent modality for excluding appendicitis. The appendix may be considered normal when it is 6 mm or less in diameter or is filled with air or oral contrast material.

- ◼

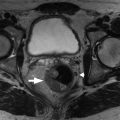

As on CT, MRI findings of appendicitis include enlargement of the appendix and associated secondary findings, such as periappendiceal inflammation ( Fig. 11.5 ).

Fig. 11.5

Acute appendicitis. The axial, fat-suppressed, T2-weighted image (A) shows appendiceal edematous mural thickening ( arrows ) with intraluminal fluid and the corresponding fat-suppressed, T1-weighted postcontrast image (B) demonstrates abnormal appendiceal mural enhancement and periappendiceal inflammation ( arrows ). The coronal, fat-suppressed, T2-weighed image (C) shows the abnormally thickened appendix throughout most of its course ( arrows ). Diffusion restriction is evident in the diffusion-weighted image ( arrows in D).

(From Roth C, Deshmukh S. Fundamentals of Body MRI , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.)

- ◼

As the gravid uterus enlarges, the cecum, and therefore the appendix, may be in atypical locations, displaced superiorly. Therefore it is helpful to identify the landmarks of the terminal ileum and cecum in attempting to localize the appendix on MRI.

Mesenteric adenitis

- ◼

Normal mesenteric lymph nodes measuring up to 4 to 5 mm in short-axis diameter can be frequently seen in up to 39% of healthy adults. The nodes are routinely identified at the mesenteric root or throughout the mesentery.

- ◼

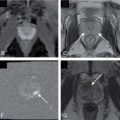

The current definition of mesenteric adenitis is the presence of a cluster of three or more lymph nodes with short-axis diameter greater than or equal to 5 mm ( Fig. 11.6 ).

Fig. 11.6

Mesenteric adenitis. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen showing a cluster of mesenteric nodes exceeding 5 mm in short axis ( arrows ) in this patient with abdominal pain.

- ◼

This definition has been described for adult patients but has limited value in children because mesenteric lymph nodes with a short-axis diameter of 5 to 10 mm are frequently found in the CT examination of children with low likelihood of mesenteric lymphadenopathy.

- ◼

Mesenteric adenitis is divided into two distinct groups: primary and secondary. It is important to differentiate between the two entities because the diagnosis influences treatment options.

- ◼

Primary mesenteric adenitis is defined as right-sided mesenteric lymphadenopathy without an identifiable acute inflammatory process or with only mild (<5 mm) wall thickening of the terminal ileum.

- ◼

Secondary mesenteric adenitis is defined as lymphadenopathy associated with a detectable intraabdominal inflammatory process. The secondary causes include appendicitis, Crohn disease, infectious colitis, ulcerative colitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and diverticulitis.

- ◼

In children, primary mesenteric adenitis is the second most common cause of right lower quadrant pain after appendicitis.

Meckel diverticulum

- ◼

Meckel diverticulum occurs in about 2% of the population ( Fig. 11.7 ). It results from failure of omphalomesenteric duct closure. Almost 96% of Meckel diverticula remain asymptomatic.