CHAPTER 7 Breast Cancer Mimics

A variety of processes, both benign and malignant, may mimic primary breast carcinoma.1–4 Many of these can be distinguished from breast cancer on the basis of imaging findings alone. However, some may ultimately require histopathologic confirmation. The most common benign causes of masses in women are fibroadenomas and breast cysts.5 High-quality imaging, including diagnostic mammography and high-resolution ultrasound and strict adherence to interpretive criteria can, for the most part, distinguish fibroadenomas and cysts from breast cancer. However, because there is sufficient overlap in the appearance of benign and malignant lesions, a new or enlarging solid mass that is not classically benign (e.g., hamartoma or lipoma) requires biopsy. In addition to lesions related to the duct-lobular system, mimics of primary breast cancer may also be caused by a wide spectrum of pathologic disorders arising in mesenchymal structures of the mammary gland. These include tumors arising in the stroma of the breast that are breast specific, such as pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH) and phyllodes tumors, as well as tumors arising from non-breast-specific stromal structures, including fibrous tissue, vascular structures, lymphoid tissue, nerves, and skin. These non-breast-specific tumors include focal fibrosis, fibromatosis, malignant fibrohistiocytomas, vascular malformations, angiosarcomas, neurofibromas, lymphomas, and liposarcomas. In addition, cancer mimics may also be caused by inflammatory processes (foreign body reaction, mastitis, and abscess), trauma (hematoma, fat necrosis), lactational changes, and metastasis from extramammary malignancies.

EPITHELIAL BREAST LESIONS

Sclerosing Adenosis

Although most breast calcifications are benign, clustered microcalcifications that do not appear classically benign on mammography (e.g., milk of calcium, vascular or rim calcifications), usually require biopsy. Sclerosing adenosis, a form of fibrocystic change, is a frequent mimicker of breast carcinoma. The mammographic findings of sclerosing adenosis include microcalcifications, a circumscribed mass, an ill-defined mass, a spiculated mass, focal asymmetry, and focal architectural distortion.6–8

Papillomas

Benign papillomas are another common breast lesion that can mimic carcinoma. Typically they present with bloody nipple discharge and occur in perimenopausal women. Mammographically, they present as single or multiple circumscribed or irregular masses, with or without microcalcifications. Sonographically, they may present as a complex intracystic lesion, intraductal lesion, or a homogeneous solid lesion. Because papillomas cannot be distinguished from papillary carcinoma or ductal carcinoma on the basis of clinical features or imaging features, biopsy is necessary.9

Radial Scars

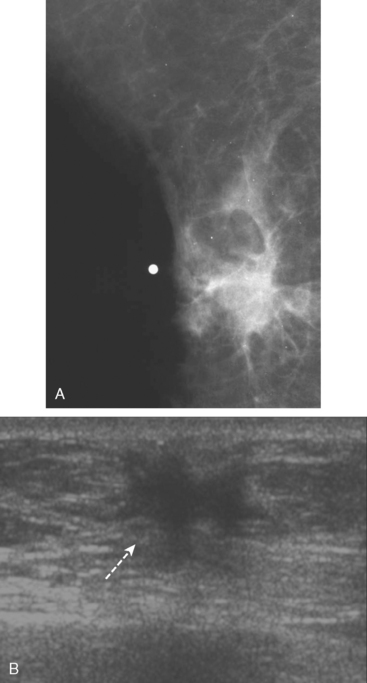

Radial scar (RS), also known as a complex sclerosing lesion, is a benign lesion that is often mistaken for carcinoma because of its spiculated appearance (Figure 1).

The pathogenesis of RS remains obscure. It has been postulated that these lesions arise as a result of unknown injury, leading to fibrosis and retraction of surrounding breast tissue. Although imaging features such as lack of a central mass and long, thin, radiating spicules help to suggest the diagnosis of RS, because they are commonly associated with atypia and malignancy, biopsy is necessary.10–11

LESIONS OF THE BREAST STROMA (BREAST SPECIFIC)

Pseudoangiomatous Stromal Hyperplasia

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia is a mesenchymal lesion composed of myofibroblasts, which sometimes includes glandular components. It is frequently a microscopic incidental finding in breast biopsies but may occasionally present as a round or oval circumscribed or partially circumscribed mass mammographically.12–15 The sonographic appearance may be variable, with most presenting as a solid, hypoechoic mass without posterior acoustic shadowing. They typically occur in premenopausal women and pathologically may be mistaken for angiosarcoma.

Phyllodes Tumor

Phyllodes tumor, also called cystosarcoma phyllodes, are unusual fibroepithelial tumors composed of epithelium and a spindle cell stroma and can exhibit a wide range of clinical behavior. Radiographically they present as a rapidly growing, hypoechoic, circumscribed mass.16 They are classified as benign, borderline, or malignant based on histopathologic features. However, histologic classification does not always predict outcome. The prognosis of phyllodes tumors is favorable, with local recurrence in about 15% of patients overall and distant recurrence in about 5% to 10%.

LESIONS OF THE BREAST STROMA (NONBREAST–SPECIFIC)

Focal Fibrosis

Focal fibrosis, also known as fibrous mastopathy, is similar to pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia. These lesions typically occur in premenopausal women and present as a circumscribed mass, irregular mass, or focal asymmetry and are hypoechoic on ultrasound. They are composed of dense collagenous stroma with sparse glandular and vascular elements.17–18

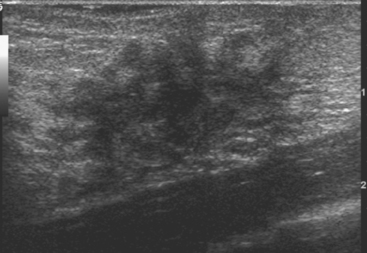

Fibromatosis

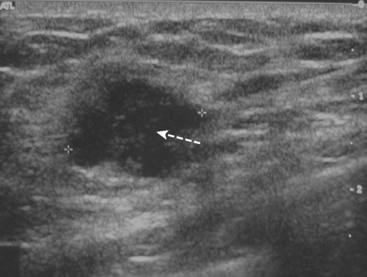

Fibromatosis, also known as extra-abdominal desmoid tumor, is an extremely rare low-grade infiltrative tumor composed of well-differentiated fibroblasts. The lesions tend to develop in the pectoralis fascia and may be fixed, causing retraction of the pectoralis muscle, skin, or nipple. On mammography, fibromatosis usually appears as a spiculated mass simulating carcinoma.19 On ultrasound, the lesions manifest as an irregular hypoechoic mass with posterior acoustic shadowing (Figure 2). Biopsy is necessary for diagnosis. Although fibromatosis does not metastasize, there is a high rate of local recurrence.

Diabetic Fibrous Mastopathy

Diabetic mastopathy is an unusual form of stromal fibrosis with lymphocytic infiltration, which typically occurs in premenopausal women with juvenile-onset insulin-dependent diabetes (type 1). Patients present with solitary or multiple nontender, hard masses. Mammography shows generalized dense tissue, and ultrasound shows an irregular hypoechoic mass with posterior acoustic shadowing (Figure 3).

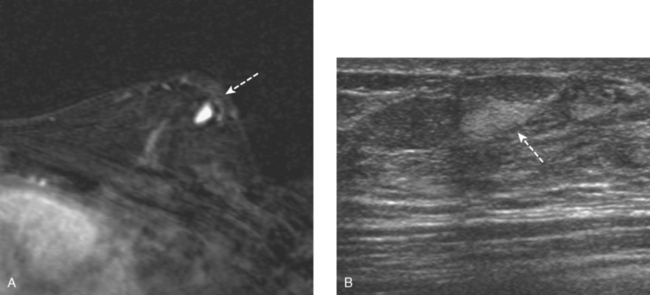

Vascular Tumors

Vascular tumors of the breast are uncommon and include hemangiomas and angiosarcomas.20 Hemangiomas are extremely rare, are usually smaller than 2 cm, and can be differentiated from dermal hemangiomas by their distinct separation from the epidermis. Mammographically, breast hemangiomas are small, well-defined, lobulated masses. On ultrasound, their appearance may be variable, being either circumscribed hypoechoic masses, mixed echogenicity masses, or ill-defined hyperechoic masses (Figure 4). Angiosarcomas of the breast are more common than hemangiomas and are usually larger in size. Radiographically, they present as an ill-defined calcified or noncalcified hypoechoic mass. They may occur in the chest wall as a rare complication following radiation therapy for primary breast cancer.

Neural Tumors

Breast tumors of neural origin are rare and include granular cell tumors and neurofibromas. Granular cell tumors are uncommon benign tumors of probable Schwann cell origin that occasionally present as a breast mass. They occur more frequently in the upper inner quadrant, corresponding to the cutaneous sensory territory of the supraclavicular nerve. Granular cell tumors occur in middle-aged, premenopausal women, usually as an irregular or spiculated hypoechoic mass with posterior acoustic shadowing. Wide local excision is generally the preferred treatment because these tend to recur if incompletely excised. Neurofibromas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors, usually occurring in the subcutaneous tissue and occasionally are found in the breast. Mammographically they appear as multiple, well-defined, benign-appearing cutaneous masses. On ultrasound, they appear as well-defined hypoechoic masses with posterior acoustic enhancement, located in the subcutaneous tissue. Clinical history usually makes the diagnosis obvious. Neurofibromas occurring in the breast are rare, are usually associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 in the pediatric patient and occur in a periareolar location.

INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION

Granulomatous Mastitis

Granulomatous mastitis of the breast is a rare entity that often presents as a palpable mass. The clinical and imaging findings may be confused with inflammatory carcinoma of the breast. The diagnosis should be suspected in patients from endemic regions. In addition to infectious causes such as tuberculosis and fungus, granulomatous mastitis may also be due to autoimmune diseases, such as sarcoidosis, or it may be idiopathic in nature.21–23

MISCELLANEOUS BREAST LESIONS

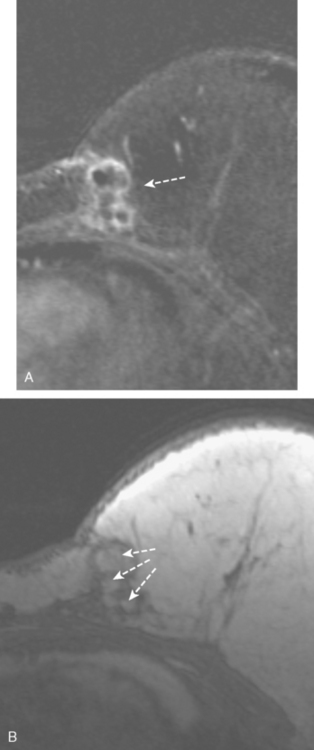

Fat Necrosis

Fat necrosis is a benign, nonsuppurative process related to breast trauma, usually from prior surgical procedures. On mammography, fat necrosis can produce changes that are similar in appearance to malignancy (Figure 5). It can appear as a hypoechoic, shadowing mass with spiculated margins that may contain indeterminate microcalcifications and can cause skin retraction.24–25 The presence of central fat or dystrophic rim calcifications is usually diagnostic. Correlation of the imaging finding with the clinical history can aid in the diagnosis.

Metastasis

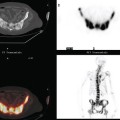

Metastatic disease should be considered when there is bilateral axillary adenopathy or multiple bilateral irregular solid masses. The most common metastatic lesions in the breast, in order of frequency, are due to lymphoma; melanoma (Figure 6); lung, ovarian, renal cell, and cervical carcinoma; and leukemia.26

Metastatic involvement of the breast from an extramammary malignancy is uncommon, with an incidence of between 0.8% and 6.6%. Rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common extramammary malignancy to metastasize to the breast in the pediatric age group but is rare in adults.

1 Iglesias A, Arias M, Santiago P, et al. Benign breast lesions that simulate malignancy: magnetic resonance imaging with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2007;36(2):66-82.

2 Porter GJ, Evans AJ, Lee AH, et al. Unusual benign breast lesions [review]. Clin Radiol. 2006;61(7):562-569.

3 Harvey JA. Unusual breast cancers: useful clues to expanding the differential diagnosis. Radiology. 2007;242(3):683-694.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree