Chapter 26 Breast imaging

Introduction and rationale

Historically, mammography has always been performed by radiographers; however, in 2000 the Department of Health announced changes to be made to the Breast Screening Programme which meant a 40% increase in skilled staff was necessary.1 To cope with the already critical shortage of radiographers and radiologists and the increase in demand a ‘Skills Mix Project in Radiography’2 was established and a four-tier structure was formed, the four tiers being:

Assistant practitioners work towards National Vocational Qualifications in the workplace, after which they are able to perform basic mammographic procedures under the supervision of a radiographer practitioner. Radiographers have the opportunity to undertake postgraduate training in order to advance their careers into clinical roles traditionally undertaken by radiologists, such as image reading, ultrasound, ultrasound reporting, and performing biopsies under ultrasound or stereotactic guidance.2

Mammography is widely used in the investigation of symptomatic breast disease and is the modality used for breast screening. The Million Women Study calculated the sensitivity and specificity of mammography by following over 120 000 women after their screening mammogram, showing sensitivity to be 86.6% and specificity 96.8%.3

Asymptomatic mammography

The National Health Service Breast Screening Programme (NHSBSP) invites all women aged 50–70 years who are registered with a general practitioner (GP) to attend for a routine 3-yearly mammogram. Asymptomatic women with a significant history of breast cancer are offered yearly mammograms between the ages of 40 and 49.4 Such women may also have a mammogram if they are taking part in a research trial.

Communication with women undergoing mammography

Essential communication stages:

• Before the mammogram, so that the woman knows what to expect and what is expected of her

• During the mammogram to ensure that she knows what is currently happening and to enable her to voice any concerns or indicate any discomfort she may be experiencing

• After the mammogram so that she knows when and how the results will be imparted

Breast screening

In 1957, the Commission of Chronic Illness in the United States defined screening as ‘the presumptive identification of unrecognised disease … by the application of tests, examinations or other procedures which can be applied rapidly’.5

No screening test can be considered perfect, but the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that there was sufficient evidence for the efficacy of breast screening of women between 50 and 69 years.6 Some essential considerations for a screening programme include:

• Is the disease an important health problem for the population?

• Can the population at risk be readily identified?

• Does early treatment lead to a better outcome?

• Are the benefits of screening greater than the harm caused?

• Does the screening identify the disease at a preclinical stage?

• Is treatment of the preclinical disease widely available?

• Is the screening modality acceptable to the target population?

In the UK mammography is currently offered every 3 years to women between the ages of 50 and 70. A pilot study currently underway may result in the age range being extended to 47–73 years.7

Mammography has been the screening modality used for every randomised trial that has shown a significant population reduction in breast cancer mortality.8–11 It has a high sensitivity in the detection of breast cancers, particularly invasive carcinomas and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).3

Publication of the Forrest Report5 on breast screening and the subsequent implementation of the NHSBSP revolutionised mammography in the UK. The report made numerous recommendations: projections that should be undertaken on each breast; the screening interval; interpretation of the mammograms; assessment and follow-up; and implementation of quality assurance and quality control procedures at every step of the programme. Recommendations regarding the setting up of an advisory committee and the Pritchard Report12 then led to guidance on quality issues. Recommendations made in the Forrest and Pritchard Reports do not pertain only to screening mammography services, as they are pertinent wherever mammography is offered, thus ensuring equity of provision for all women.

Breast disease demonstrated with mammography

Benign breast conditions

There are a number of benign breast conditions that may manifest on mammograms. Some examples are:

• Benign breast change: There is no evident disease process and changes are often brought about by hormonal variations. Conditions such as mastitis and fibroadenosis would come under this umbrella.

• Cysts: Cystic changes in the breast are very common and, as with most benign breast conditions, tend to be bilateral.

• Fibroadenoma: These are often found incidentally as they are usually too small to feel. Larger lesions occur in younger women. Fibroadenomas in postmenopausal women do not grow (except in women on hormone replacement therapy) and new lesions seldom appear.

Benign breast conditions and their mammographic appearances

| Cysts | Visualised as an increase in density usually with smooth edges |

| Fibroadenoma | Has no specific characteristic features but is usually smooth, rounded, well defined, and causes displacement of the surrounding tissues. When calcification occurs the lesion is said to have a ‘popcorn’ appearance |

Breast cancer

United Kingdom breast cancer facts and statistics:13

• Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women

• The lifetime risk of developing cancer of the breast is 1 in 8

• 80% of breast cancers occur in postmenopausal women

• 5–10% of breast cancers are hereditary

• 90% of breast lumps are benign

• Around 300 men are diagnosed in the UK each year

• Breast cancer can be divided into two main types:

In situ carcinoma: this is contained within the breast ducts or lobules, although it has the potential to become invasive

In situ carcinoma: this is contained within the breast ducts or lobules, although it has the potential to become invasive Invasive carcinoma: this has spread from the ducts or lobules into the surrounding breast tissue. It has the potential to metastasise, via the blood or lymphatic systems, to other parts of the body and may ultimately shorten the patient’s life. Invasive cancers are graded histologically from 1 to 3, according to how similar the breast cancer cells are to normal cells of the same type. The higher the grade the more different the cancer cells are from normal cells and the more rapidly they reproduce14

Invasive carcinoma: this has spread from the ducts or lobules into the surrounding breast tissue. It has the potential to metastasise, via the blood or lymphatic systems, to other parts of the body and may ultimately shorten the patient’s life. Invasive cancers are graded histologically from 1 to 3, according to how similar the breast cancer cells are to normal cells of the same type. The higher the grade the more different the cancer cells are from normal cells and the more rapidly they reproduce14Cancer type and mammographic appearance

| Cancer type | Appearance |

|---|---|

| DCIS | Microcalcifications |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | Usually spiculate mass, but often has calcification and parenchymal distortion |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | Similar to ductal carcinoma but microcalcification is less common |

Dose implications for the breast undergoing mammography

It is important to remember that mammography uses radiation and therefore has the potential to induce carcinoma by the biological effects of radiation. The risk is considered to be low for the patient undergoing a single mammogram because the dose is well below the threshold for deterministic effects, and the reproductive cells are not exposed to primary radiation. Risks are highest in young women and are estimated to range from 9.1 fatal carcinomas induced per million per mGy in the 30–34-year age group, falling to 7.5 fatal carcinomas induced per million per mGy in the 45–49-year age group and 4.7 fatal carcinomas induced per million per mGy in the 60–64-year age group.11

For women of screening age in the UK the risk of radiation-induced breast cancer (including non-fatal tumours) is approximately 1 in 100 000 per mGy. Radiation dose for women attending the NHSBSP is taken to be on average 4.5 mGy per two-view screening examination. The risk of radiation-induced cancer for a woman attending mammographic screening (two views) by the NHSBSP is about 1 in 20 000 per visit, and it is estimated that about 170 cancers are detected by the NHSBSP for every cancer induced.15

Digital mammography

The NHSBSP approved the use of digital mammography for breast screening following the results of the Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (DMIST), which enrolled almost 50 000 women. Each woman in the trial underwent both film mammography and digital mammography and various factors were recorded, such as the age of the woman, density of the breast, thickness of the compressed breast, and radiation dose. Digital and film mammograms were reported separately before being compared, and it was determined that the sensitivity of film mammography was comparable to that of digital mammography in women with fatty breasts. However, in women with dense breasts the trial demonstrated significantly improved sensitivity of digital mammography over film mammography. Furthermore, the trial revealed that the radiation dose with digital mammography was 22% less than with film mammography.16 In 2007 the Department of Health stated that all screening units should have at least one digital mammography set by 2010.17

Alternative and complementary imaging techniques

Magnetic resonance mammography (MRM)

MRM is increasingly used as an adjunct to mammography and ultrasound, although it currently has disadvantages such as high cost, limited availability and several contraindications (women with pacemakers, pregnant women, those with claustrophobia and women who are unable to lie in the required prone position, which is necessary when using a breast coil). It is, however, particularly useful for:18

Nuclear medicine

There are two main uses of nuclear medicine in breast imaging:

1 Sentinel node biopsy. This involves the use of technetium-labelled colloid to label the first axillary lymph node to drain the breast – the sentinel node. If this node is metastasis free then axillary clearance can be avoided. Sentinel node status is able to accurately predict axillary lymph node status in over 95% of cases.19

2 Scintimammography. This involves the use of technetium-labelled sestamibi and, used as an adjunct to mammography, is comparable to MRM in both sensitivity and specificity in the demonstration of both palpable and impalpable tumours.18

Digital breast tomosynthesis

Some newer digital mammography sets have this function. The woman is positioned as for a normal mammogram, but with a little less compression. The tube then moves over the breast in an arc, taking a series of low-dose images as it moves. Once these images have been reconstructed (a matter of seconds) a three-dimensional image is produced which is displayed as slices throughout the breast, much like a CT scan. This is particularly useful for dense breasts as it eliminates the problem of overlapping tissue. The use of tomosynthesis as part of a breast screening programme has been trialled in the US and results so far have demonstrated that, when performed as an adjunct to digital mammography, there is a 30–40% reduction in women being recalled for assessment.20,21 When tomosynthesis is performed without digital mammography the recall rate is reduced by 10%.20,21 Research is currently under way at King’s College Hospital in London to look into the potential of using tomosynthesis within the NHS breast screening programme.22

Mammography technique

Equipment

The purchase, commissioning and quality control of suitable equipment are essential for the provision of a quality mammography service.23 Equipment must be acceptable to both the operator and the client: it must be light and easy for the operator to use, and there must be no sharp edges in the sections of the unit that come into contact with the client. In addition, handles are necessary to help the client maintain the correct arm position for the oblique projection and for support, if necessary.

The machine consists simply of an X-ray tube connected to a breast support which houses the imaging detector on a C-shaped arm, with a moveable compression paddle between the two (Fig. 26.1).

Functional requirements

• High-voltage generator. The generator must supply a near DC high voltage with ripple less than 5%.

• Kilovoltage (kVp) output. Most modern mammography machines have automatic selection for kVp in order to optimise contrast. The generator provides a constant potential and the high voltage applied to the tube must be from 22 to 35 kVp in increments of 1 kVp.

• Focal spot size. The focal spot should be as small as possible to ensure adequate resolution, for example 0.3 mm for general mammography and 0.1 mm (small focus) for magnification views.

• Tube current (mA). In order to keep exposure times to a minimum (and thus reduce the likelihood of movement unsharpness) the tube current should be as high as possible. At 28 kVp the current should be at least 100 mA on large focus.

• Grid. A grid is essential to ensure optimum image quality; this may be incorporated within the detector on some digital systems.

• AED. An automatic exposure device is essential because of the wide variation in breast sizes and compositions. (As there is a need for high radiographic contrast and hence the system has low latitude, there is little scope for error in the selection of mAs.)23

Viewing images

Digital mammography images can be viewed on any monitor linked to the network. However, for reporting purposes high-resolution 5 megapixel monitors are required.24

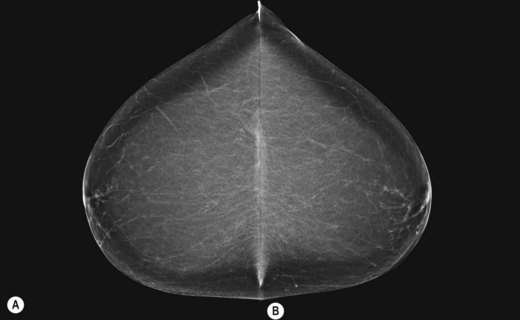

It is recommended that craniocaudal (CC) images are viewed ‘back-to-back’ with the posterior aspects of the breasts touching (Fig. 26.2A,B). Mediolateral obliques are viewed with the pectoral aspects touching (Fig. 26.3A,B). These strategies facilitate vital comparison of similar areas of each breast for each projection.

Figure 26.2 Mounting craniocaudal images for viewing.

(Permission to use images by courtesy of IMS Italy).

Mammographic projections

Craniocaudal (CC) (Fig. 26.4A,B)

Positioning

• The mammography unit is positioned with the image receptor (IR) holder horizontal and the height adjusted to slightly above the level of the inframammary angle

• The client faces the machine, standing approximately 5–6 cm back from it

• The client’s arms hang loosely by her side and her head is turned away from the side to be examined

• The breast is lifted gently up and away from the chest wall (the mammographer will use the left hand to raise the right breast and the right hand to raise the left breast)

• With the mammographer supporting the breast, the height of the unit is adjusted so that the IR holder makes contact with the breast at the inframammary fold and the breast is at approximately 90° to the chest wall

• The client is asked to lean slightly forward until her rib cage is in contact with the machine. The breast is carefully placed onto the IR holder, ensuring that no skin folds are created underneath the breast

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree