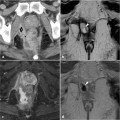

Fig. 26.1

A 38-year-old female patient with long-standing Crohn’s disease, and previous surgical treatment for anovaginal fistula and abscess was investigated due to anal swelling and bleeding. Clinical examination disclosed perianal fistulous tracts with purulent secretion. Contrast-enhanced CT images (a, b) show an inhomogeneous, largely necrotic mass centered in the anus, associated with fluid-containing fistulous tracts in the left ischioanal space. Mucinous adenocarcinoma was treated with abdominoperineal anorectal amputation26 Cancer in Perianal Fistulas

In the presence of lesions of the anal canal, imaging techniques that include endoanal sonography and MRI probes are hampered by the pain experienced by the patient and by technical difficulties during probe positioning. Furthermore, endoanal imaging combines a very high degree of spatial detail with a limited field-of-view that does not allow comprehensive assessment of lymphatic spread [7]. Although CT may visualize anal cancers, MRI performed using external phased-array coils is the imaging modality of choice to assess primary treated lesions as well as recurrent ones, thus allowing pretreatment staging and radiotherapy planning [1, 7]. The acquisition protocols are mostly similar to those described for perianal inflammatory disease and rely heavily on multiplanar T2 sequences. The only important difference consists of the usual lack of post-gadolinium sequences since according to most centers contrast-enhanced MRI acquisitions do not add significant information to those obtained from the intrinsic tissue contrast of high-resolution T2-weighted images [2, 7].

MRI provides a detailed visualization of the anal canal and nearby anatomic structures, with the notable exception that the dentate line is not recognizable. Neoplastic processes show low or intermediate T1 signal intensity and positive, usually intense enhancement after intravenous gadolinium contrast [1, 7]. On T2-weighted and STIR sequences, tumor tissue has an intermediate signal intensity, lower than that of normal ischioanal fat and almost always higher than the internal reference standard, i.e., uninvolved anal sphincters and gluteal muscles (Fig. 26.2) [1, 2].

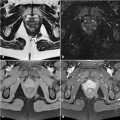

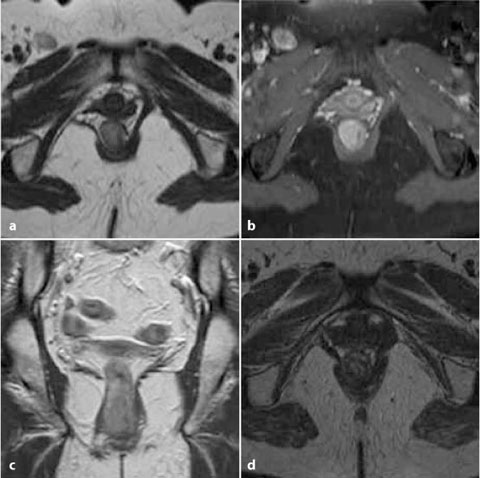

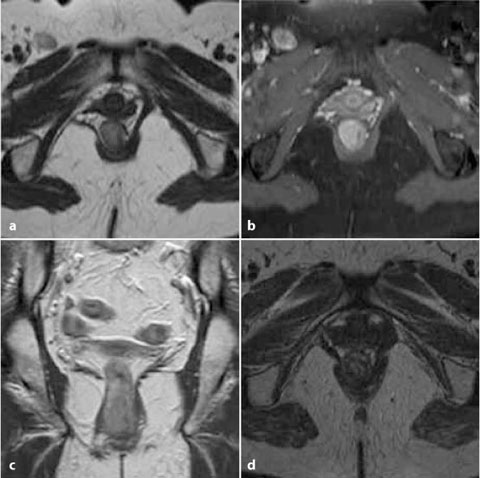

Fig. 26.2

A 46-year-old female patient with clinical and biopsy diagnosis of squamous cell anal carcinoma. MRI was requested to stage the disease. Axial T2-weighted (a), contrast-enhanced axial fat-saturated (b), and coronal (c) T1-weighted images after intravenous gadolinium show eccentric mural thickening of the anus with increased T2 signal intensity and strong homogeneous contrast enhancement with a maximum longitudinal diameter measuring 3 cm. Right inguinal adenopathy, with analogous signal and enhancement features consistent with nodal metastasis was determined. Following chemoradiotherapy, the axial T2-weighted image (d) shows the near-complete disappearance of both the anal neoplastic solid tissue and the lymphadenopathy

In 2010, the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommended MRI as the primary imaging modality for staging anal carcinoma [8]. Accurate staging is essential in terms of providing prognostic information and in guiding the correct therapeutic choice. It is based on the UICC/AJCC TNM classification shown in Table 26.1. Parameters to be assessed by imaging include the size of the primary lesion, the presence of metastasis in the perirectal, inguinal, or internal iliac lymph nodes, and possible invasion of the adjacent organs. At initial presentation half of the patients have shown a superficial (up to T2) tumor and 25% of them regional lymph node involvement [2, 7].

Table 26.1

TNM staging of anal cancer

Primary tumor (T) | |

TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

T1 | Tumor ≤ 2 cm in its greatest dimension |

T2 | Tumor 2–5 cm in its greatest dimension |

T3 |

|