Cartilage-Forming (Chondrogenic) Lesions

Diagnosis of a bone lesion as originating from cartilage is usually a simple task for the radiologist. The lesion’s radiolucent matrix, scalloped margin, and punctate, annular, or comma-shaped calcifications usually suffice to establish its chondrogenic nature. Yet determination if a cartilage tumor is benign or malignant, often creates a problem for the radiologist and even for the pathologist. All cartilage tumors, regardless if benign or malignant, exhibit a positive reaction for S-100 protein, a helpful diagnostic hint. Histologically, cartilaginous lesions are usually recognized by the features of their intercellular matrix, which has a uniformly translucent appearance and contains less collagen than do the bone-forming tumors. The tumor cells are located in rounded spaces, called lacunae, as in normal cartilage. In benign cartilage tumors, like enchondroma, the tissue is sparsely cellular. The cells usually contain small darkly stained nuclei. The tumor tissue is avascular, and areas of calcified matrix are common. Because of their slow growth, enchondromas expand into the endocortex creating small erosions (scalloping). Conversely, chondrosarcomas exhibit pleomorphism, large nuclei, double nuclei, and mitoses. These tumors invade the endocortex, form deep scalloping, and are associated with cortical thickening, periosteal reaction, and not infrequently a softtissue mass.

A. BENIGN CARTILAGE-FORMING LESIONS

Enchondroma

Definition:

Benign hyaline cartilage neoplasm arising in the medullary portion of bone.

Epidemiology:

Ten to twenty-five percent of all benign bone tumors.

Age range from 5 to 80 years.

Most common in the second through fourth decades of life.

Solitary enchondromas are rare in young children, whereas multiple enchondromas are encountered more commonly.

Both genders are equally affected.

Sites of Involvement:

Any bone formed by endochondral ossification can be affected.

Common in the short tubular bones (phalanges and metacarpals) of the hands, followed by bones of the feet, and the long bones, especially proximal humerus and proximal and distal femur.

In the long bones, the tumors are usually centrally located within metaphysis or diaphysis.

Epiphyseal involvement is rare.

Clinical Findings:

In the small bones of the hands and feet typically presents as palpable swellings, with or without pain.

Common expansion of small bones and attenuation of the cortex may cause pathologic fractures, which may resemble aggressive malignant behavior.

In the long bone, tumors are more often asymptomatic and are detected incidentally in the imaging studies obtained for other reasons.

Imaging:

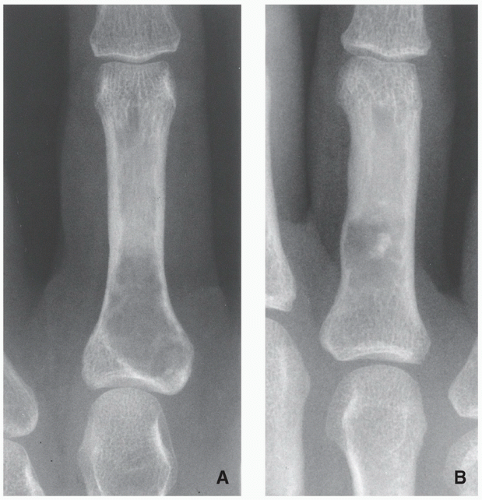

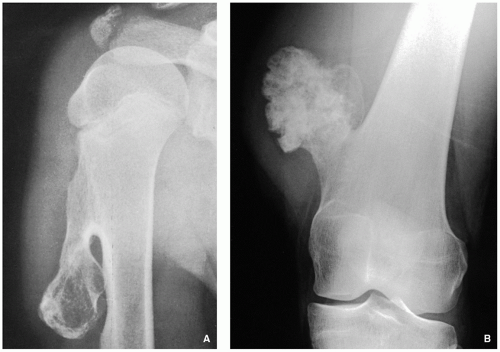

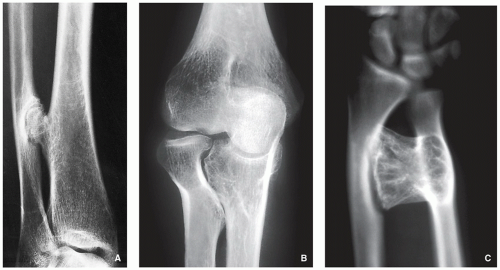

Radiography shows well-marginated lesion that vary from radiolucent to heavily mineralized (calcified) (Figs. 3.1 and 3.2).

Cortex is usually thinned out and expanded in symmetric fusiform fashion.

Calcification pattern is characteristic, consisting of punctate (stippled), flocculent, or curvilinear (in form of ring, comma-shaped, and arc pattern) calcifications, exhibiting “popcorn”-like appearance (see Figs. 1.6C, 1.17, 1.18A, and 3.2).

Lesions in the small tubular bones can be centrally or eccentrically located, and larger tumors may completely replace medullary cavity.

Occasionally, intracortical lesions are present, resembling osteochondromas (see Fig. 3.12).

Shallow endosteal scalloping is usually present (see Fig. 3.2C).

There is no periosteal reaction, unless pathologic fracture has occurred.

Cortical destruction and soft-tissue invasion should never be seen in enchondromas and would be most consistent with chondrosarcoma.

Skeletal scintigraphy shows mildly increased uptake of radiopharmaceutical agent in uncomplicated lesions, whereas the presence of a pathologic fracture or malignant transformation is revealed by marked scintigraphic activity.

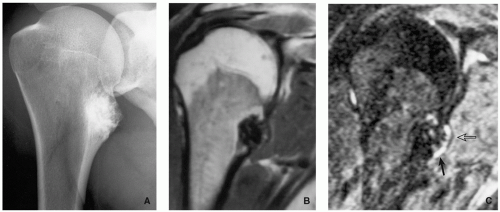

Computed tomography further delineates the tumor and more precisely localizes it in the bone; it shows to better advantage the scalloped borders and matrix calcifications.

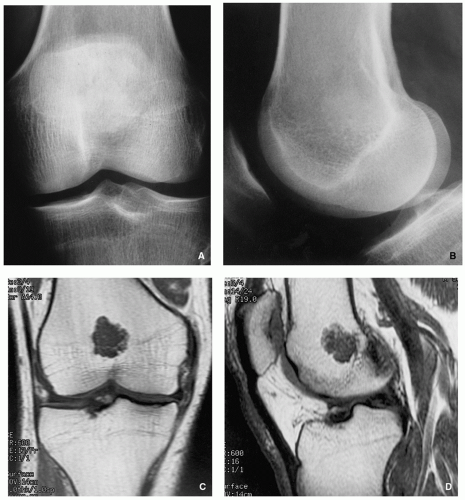

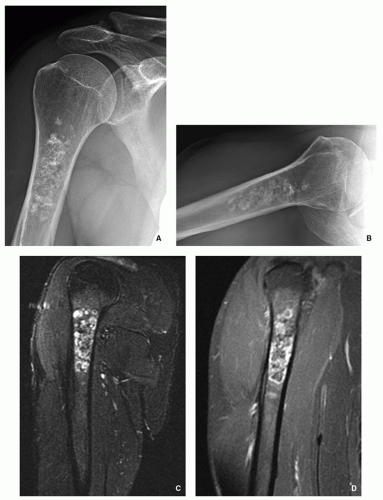

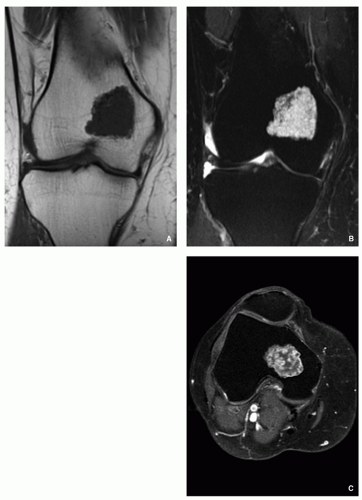

Magnetic resonance imaging—T1-weighted sequences show the lesion to be of low-to-intermediate signal intensity, whereas on T2-weighted and other watersensitive sequences, the lesions will exhibit high signal, with calcifications imaged as low signal intensity structures (Figs. 3.3 and 3.4). After intravenous administration of gadolinium, there is enhancement of the lesion (Figs. 3.5D and 3.6C).

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

Most enchondromas measure less than 3 cm in length, and tumors larger than 5 cm are uncommon.

Cartilaginous multinodular architecture is separated by bone marrow.

Multinodular pattern is seen more often in long bones compared to confluent growth pattern in small tubular bones.

Histopathology:

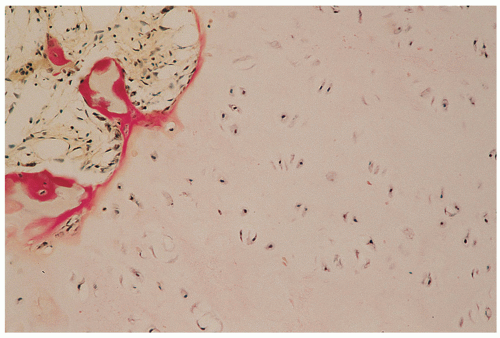

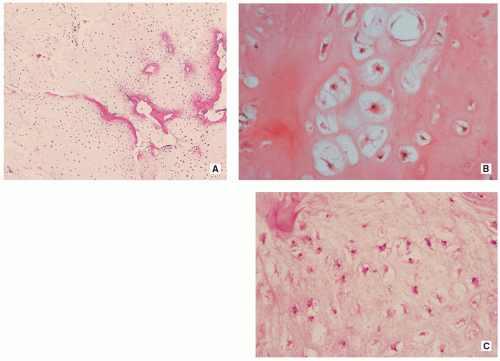

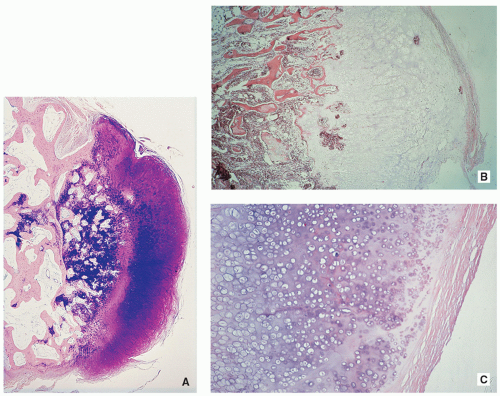

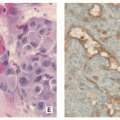

Cartilage nodules may cause shallow impressions on endocortex, but no invasion is present (Fig. 3.7).

Cartilage nodules frequently undergo endochondral ossification (Fig. 3.8).

Cartilage shows low-to-moderate cellularity and contains chondrocytes of variable size located in the lacunae, exhibiting small, round, and hyperchromatic nuclei (Figs. 3.9A,B and 3.10B).

Occasionally, scattered binucleated cells are present (Fig. 3.9C).

Nodules of hyaline cartilage are well demarcated by the surrounding bone and bone marrow (Fig. 3.10A).

Calcifications may be present.

Genetics:

Structural abnormalities involving chromosomes or chromosomal regions 4q, 7, 11, 14q, 16q22-q24, 20, and particularly rearrangement of chromosome 6 and 12q12-q15.

Complications:

Pathologic fracture.

Malignant transformation.

Prognosis:

Solitary enchondromas are successfully treated by intralesional curettage in most cases, and local recurrences are uncommon.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Medullary bone infarct

Well-defined, sclerotic, serpentine border.

Lack of endosteal scalloping.

MRI (water-sensitive sequences) shows characteristic double-line signal intensity pattern.

▪ Low-grade chondrosarcoma

Length of the lesion greater than 5 cm.

Thickening of the cortex.

Deep endosteal scalloping.

Histopathology shows increased cellularity, cytologic atypia, hyperchromasia of the nuclei and binucleasion, and occasionally stromal myxoid changes.

Permeation and entrapment of bone trabeculae.

Enchondromatosis, Ollier Disease, and Maffucci Syndrome

Enchondromatosis—two or more enchondromas not associated with bone deformities or growth disturbance (Figs. 3.11 and 3.12).

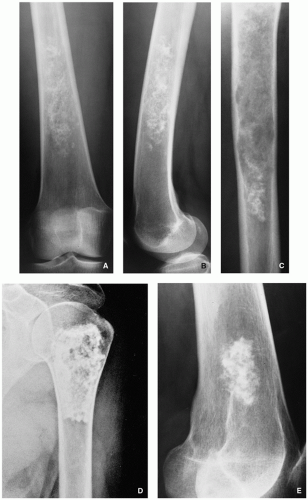

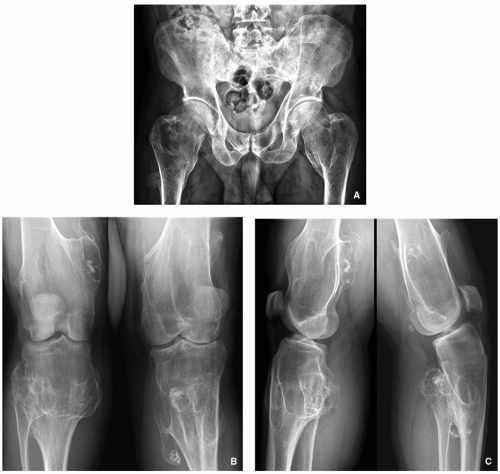

Ollier disease (nonhereditary disorder)—multiple enchondromas with strong preference for one side of the body (monomelic distribution), associated with bone growth disturbance (Figs. 3.13, 3.14, 3.15 and 3.16).

Maffucci syndrome (nonhereditary disorder)—Ollier disease associated with hemangiomas of soft tissue (Figs. 3.17 and 3.18).

Clinical features of both conditions are knobby swelling of the digits and gross disparity in the length of the forearms and legs.

Clinical behavior of these conditions is unpredictable, and there is no specific treatment.

Most serious complication is malignant transformation of an enchondroma in Ollier disease (25% to 30% of affected patients) and Maffucci syndrome (greater than 50%) (see Fig. 3.18).

Patients with these conditions must have lifetime monitoring of their tumors.

Histologically, the enchondromas of these entities are similar to those of sporadic solitary tumors; however, they frequently demonstrate a greater degree of cellularity, demonstrate cytologic atypia, and may contain myxoid stroma, which may suggest the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma.

Periosteal (Juxtacortical) Chondroma

Definition:

Benign cartilaginous lesion, almost identical to enchondroma, but growing on the surface of the bone in or beneath the periosteum.

Epidemiology:

Less than 2% of all benign cartilaginous lesions.

Most common in the second and third decades of life.

Children and adults are equally affected.

Sites of Involvement:

Long and short tubular bones with most common location in the proximal humerus.

Clinical Findings:

Common presentation as palpable, often painful mass.

Imaging:

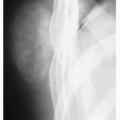

Radiography shows cartilaginous lesion on the surface of the bone, with or without cortical erosion, that may contain calcifications, commonly associated with a buttress of periosteal reaction (Figs. 3.19 and 3.20); larger lesions resemble sessile osteochondromas (Fig. 3.21).

CT and MRI demonstrate separation of the lesion from the medullary portion of host bone (Figs. 3.21 and 3.22).

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

Well-marginated bone surface tumors.

Cortex underlying the tumor is usually thickened and may be eroded.

Most of the time, tumors are less than 6 cm in greatest diameter.

Histopathology:

Can be more cellular than enchondroma, occasionally cellular atypia is present (Fig. 3.23).

Prognostic Factors:

Recurrence rate is low after total excision.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Sessile osteochondroma

Continuity of the cortices of the lesion and host bone.

Continuity of the cancellous portions of the lesion and host bone.

FIGURE 3.16 Magnetic resonance imaging of Ollier disease. (A) Anteroposterior radiograph of the right humerus of the same patient as depicted in Fig. 3.15 shows numerous enchondromas affecting proximal half of the bone. (B) Coronal T1-weighted MR image shows heterogeneous but predominantly low signal intensity of the lesions. |

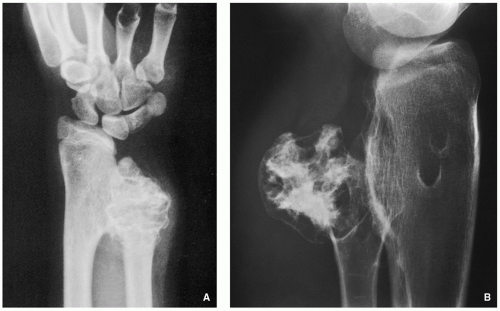

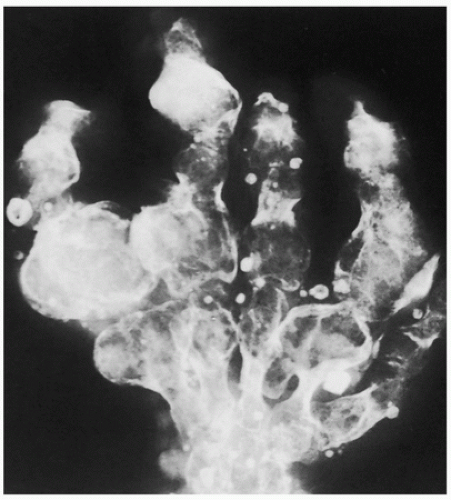

FIGURE 3.17 Radiography of Maffucci syndrome. Typical changes of this disorder consist of multiple enchondromas and softtissue hemangiomatosis, manifested by calcified phleboliths. |

▪ Periosteal osteoblastoma

Thin shell of newly formed periosteal bone usually covers the lesion.

Bone formation within the lesion.

Histopathology shows osteoid and immature bone trabeculae produced by osteoblasts.

Soft-Tissue Chondroma

Sites:

Hands and feet.

Clinical Findings:

Usually asymptomatic.

Imaging:

Radiography shows small (2 to 4 cm) well-defined softtissue masses with chondroid type of calcifications.

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

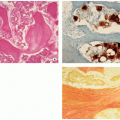

Well-circumscribed cartilaginous nodule.

Histopathology:

Lesion composed of lobules of hyaline cartilage covered by fibrous tissue (Fig. 3.24).

Sometimes partially myxoid, moderately cellular tissue with hyperchromatic nuclei.

May contain focal areas of fibrosis, hemorrhage, necrosis, calcifications, and granuloma formation.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Myositis ossificans

Imaging modalities and histopathology show lack of cartilage formation and classic zonal phenomenon (outer layer of mature bone formation and inner layer composed of reactive proliferation of spindle cells).

▪ Synovial sarcoma

Lower extremities more commonly affected.

May invade the adjacent bone.

Periosteal reaction may be observed.

MRI shows characteristic “triple-signal- intensity” pattern.

Histopathology shows biphasic appearance with gland-like spaces and spindle cell sarcomatous areas; positivity for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and for bcl2 and CD99, but negative for S-100 protein.

▪ Soft-tissue chondrosarcoma

Larger lesion.

Histopathology shows undifferentiated mesenchymal cells with only rare islands of well-differentiated cartilage; frequent myxoid changes; and permeation and entrapment of bone trabeculae.

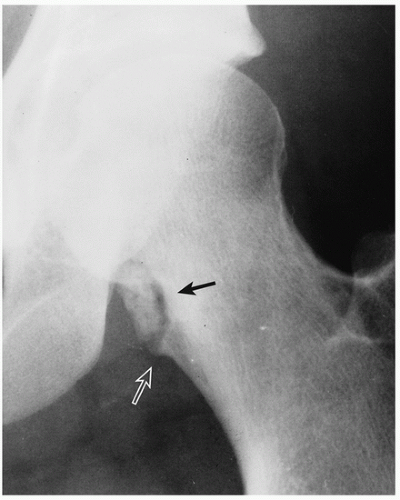

FIGURE 3.20 Radiography of periosteal chondroma. A cartilaginous lesion is eroding the medial cortex of the neck of the femur (arrow) evoking a buttress of periosteal reaction (open arrow). |

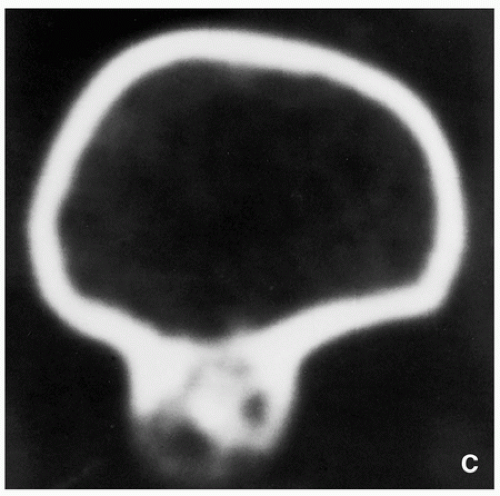

FIGURE 3.21 (Continued). (C) Computed tomography section demonstrates that the lesion is separated from the host bone by femoral cortex. |

Synovial (Osteo) Chondromatosis

Definition:

Benign metaplastic nodular cartilaginous proliferation arising in the synovial membrane of joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths.

Epidemiology:

Uncommon condition.

Mostly seen in adults.

Male-to-female ratio of 2:1.

Sites of Involvement:

Most of the time only one joint is involved.

Most common involvement of the knee followed by the hip, elbow, wrist, ankle, and shoulder joint.

Clinical Findings:

Nonspecific symptoms with recurrent pain, swelling, joint effusion, and stiffness of joint.

Sometimes lesion may present as painless soft-tissue mass adjacent to a joint.

Imaging:

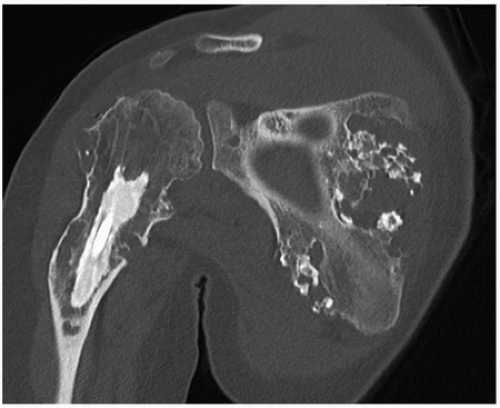

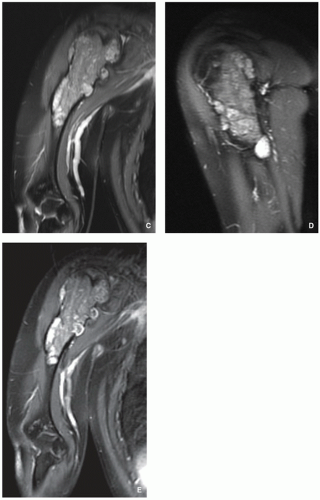

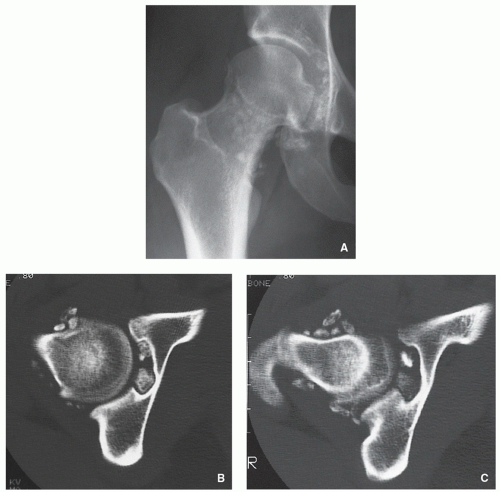

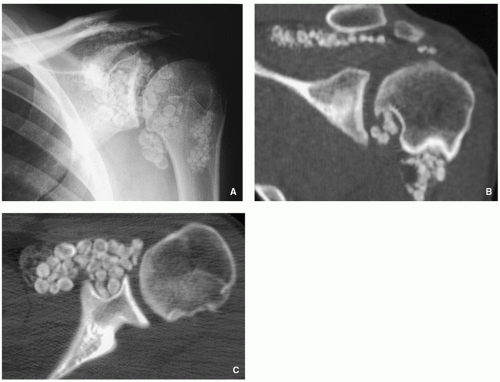

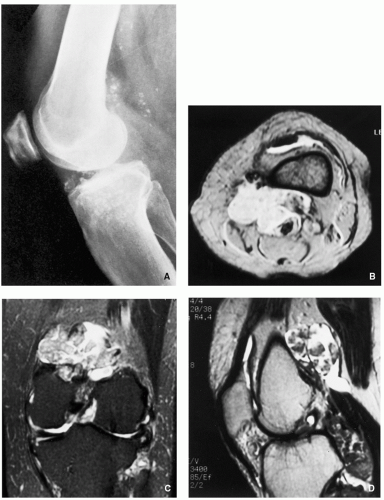

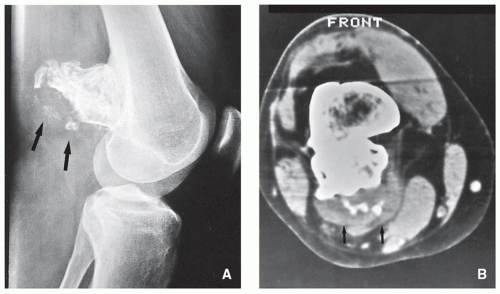

Radiographic findings depend upon the degree of calcification within the cartilaginous bodies, ranging from joint effusion only to visualization of many radiopaque joint bodies (Figs. 3.25 and 3.26). The bodies are small and uniform in size.

CT and MRI demonstrate intra-articular loose bodies (even noncalcified), bone erosion, and (rare) extracapsular extension of the lesion (Figs. 3.27, 3.28 and 3.29).

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

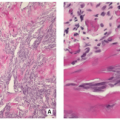

Multiple blue/white ovoid bodies or nodules within synovial tissue (Fig. 3.30).

Nodules may measure from a millimeters to several centimeters.

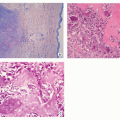

Histopathology:

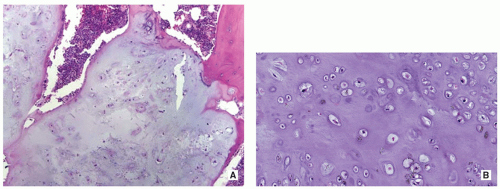

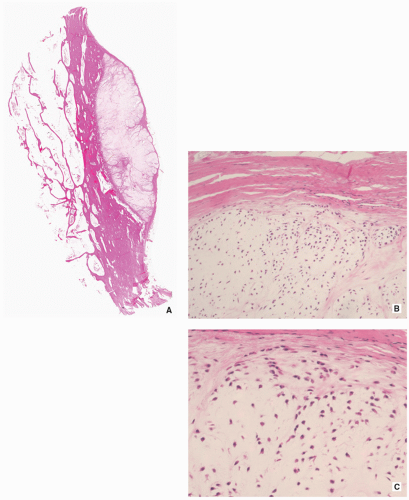

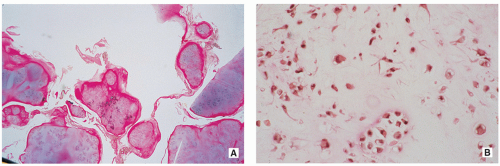

Variably cellular hyaline cartilage nodules covered by a fibrous tissue with synovial lining (Figs. 3.31 and 3.32A).

Chondrocytes may form clusters with plump nuclei, and some of them may show moderate nuclear enlargement and binucleated cells (Fig. 3.32B).

Uncommon mitotic figures.

Ossifications and fatty marrow in intertrabecular spaces may be seen.

Genetics:

Most cases show near-diploid or pseudodiploid karyotypes with some cases showing only simple numerical changes (-X, -Y, and +5, respectively).

Some cases may display rearrangement of the bands 1p13-p22.

Prognostic Factors/Complications:

Self-limiting process with potential local recurrence.

Bone erosion has been described.

Rare cases of chondrosarcoma arising in synovial chondromatosis were described.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Secondary osteochondromatosis (complication of osteoarthritis)

The osteochondral bodies are larger and not uniform in size.

Affected joint shows degenerative changes (osteoarthritis).

FIGURE 3.30 Gross specimen of synovial (osteo)chondromatosis. Multiple blue/white ovoid nodules of cartilage are scattered within the synovial tissue. |

Osteochondroma (Osteocartilaginous Exostosis)

Definition:

Cartilage-capped osseous projection (either sessile or pedunculated) arising on the external surface of a bone exhibiting an uninterrupted merging of the cortex of the host bone with the cortex of the lesion and communication of the medullary portions of the lesion and adjacent bone.

Epidemiology:

Most common benign bone lesion (20% to 50% of all benign bone tumors).

May be solitary or multiple, the latter occurring in the setting of hereditary multiple exostoses.

Solitary lesions account for 80% of cases.

Most common in the second decade of life.

Male-to-female ratio of 1.5-2:1.

Sites:

Most common sites: metaphyseal region of the distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal tibia and fibula.

Clinical Findings:

Most common presentation is that of a hard mass of longstanding duration.

Majority of the lesions are asymptomatic and found incidentally.

Symptoms are often related to the size and location of the lesion, pressure on the nerve or blood vessels, pathologic fracture, or bursitis exostotica.

Imaging:

Radiography shows bulbous, cauliflower-like lesions (Fig. 3.33).

The characteristic feature is continuation of the cortex of the lesion with that of a host bone and communication of the respected medullary portions (Figs. 3.34, 3.35 and 3.36).

Calcifications in the chondro-osseous junction of the lesion (see Figs. 3.33B and 3.34A).

Excessive cartilage-type flocculent calcifications, particularly dispersed calcifications into the cartilaginous cap, should raise the suspicion of malignant transformation (see Fig. 3.46 and Table 3.1).

TABLE 3.1 Clinical and Imaging Features Suggesting Malignant Transformation of Osteochondroma

Clinical Features

Radiologic Findings

Imaging Modality

Pain (in the absence of fracture, bursitis, or pressure on nearby nerves)

Enlargement of the lesion

Conventional radiography (comparison with earlier radiographs)

Growth spurt (after skeletal maturity)

Development of a bulky cartilaginous cap usually more than 2-3 cm thick

CT, MRI

Dispersed calcifications in the cartilaginous cap

Development of a soft-tissue mass with or without calcifications

Radiography, CT, MRI

Increased uptake of isotope after closure of growth place (not always reliable)

Scintigraphy

From Greenspan A, Beltran J. Orthopedic Imaging. 6th ed. Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia 2015:745, Table 18.1.

CT and MRI typically show unequivocally the lack of cortical interruption and the continuity of cancellous portions of the lesion and the host bone (Figs. 3.37, 3.38 and 3.39). These modalities also demonstrate the thickness of the cartilaginous cap.

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

May be sessile (Fig. 3.40) or pedunculated.

The cortex and medullary cavity of the host bone extend into the lesion.

The cartilage cap is usually thin.

A thick cap (greater than 2 cm) may be indicative of malignant transformation.

Histopathology:

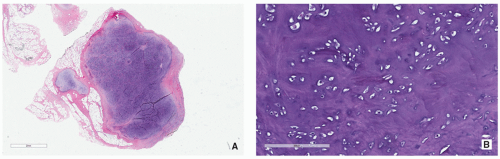

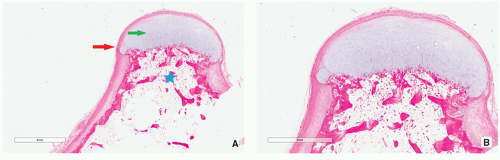

The lesion has three layers—perichondrium (fibrous layer covering cartilage), cartilage, and bone (Figs. 3.41 and 3.42).

The outer layer is a fibrous perichondrium that is continuous with the periosteum of the underlying bone.

Underneath there is a cartilage cap that is usually less than 2 cm thick (thickness decreases with age).

Within the cartilage cap, the superficial chondrocytes are clustered, whereas the ones close to bone resemble growth plate.

Loss of the architecture of cartilage, wide fibrous bands, myxoid change, increased chondrocyte cellularity, mitotic activity, significant chondrocyte atypia, and necrosis are all features that may indicate secondary malignant transformation.

Genetics:

Chromosomal aberrations involving EXT1 gene 8q22-24.1 and EXT2 11p11-p12 defect.

Complications:

Fracture of the lesion.

Pressure/erosion and fracture of the adjacent bone (ulna, fibula) (Figs. 3.43 and 3.44).

Bursitis (bursa exostotica) (Fig. 3.45).

Pressure on nerves and blood vessels.

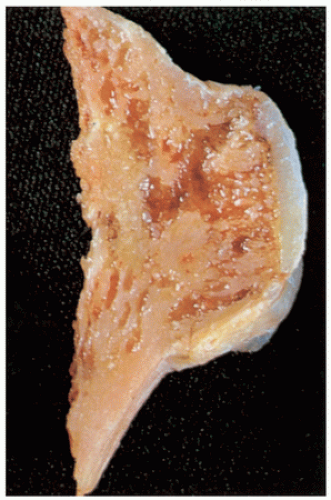

FIGURE 3.40 Gross specimen of sessile osteochondroma. Note continuity of the cortex and medullary cavities, and thin cartilaginous cap.

Malignant transformation to chondrosarcoma (less than 1% in solitary lesions) (Fig. 3.46).

Prognosis:

Excision is usually curative.

Recurrence is seen with incomplete removal.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Periosteal chondroma

Lesion separated from the host bone but may erode the cortex.

Large lesion may mimic osteochondroma but lack cortical and medullary continuity.

Value of attenuation coefficient of the lesion as determined by CT (Hounsfield values) is helpful in differential diagnosis: base of osteochondroma has higher values than does that of periosteal chondroma.

▪ Trevor-Fairbanks disease (dysplasia epiphysealis hemimelica, intra-articular osteochondroma)

Asymmetric cartilaginous overgrowth of one or more epiphyses.

Talus, distal femur, and distal tibia most commonly affected.

Histopathologically almost identical with osteochondroma.

▪ BPOP (Nora lesion, bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation)

Usually affects the metacarpals and phalanges of the hand.

Mushroom-like-shaped osseous or cartilaginous mass attached to the cortex.

Lack of communication with medullary cavity of the host bone.

▪ Juxtacortical (parosteal) osteoma

Homogenously dense, sclerotic, ivory-like mass.

No communication with the medullary portion of the host bone.

Histopathology shows compact, dense, mature lamellar bone, or woven bone formation with transformation to lamellar bone, and osteocyte lacunae.

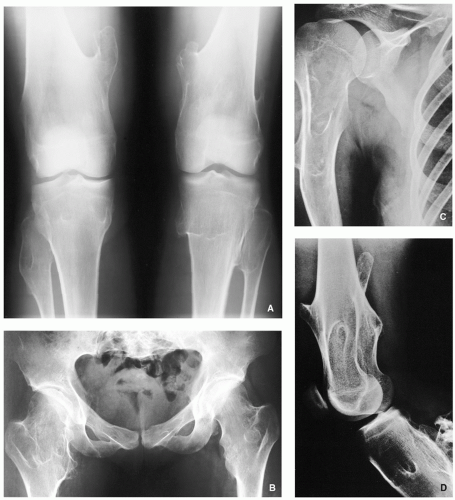

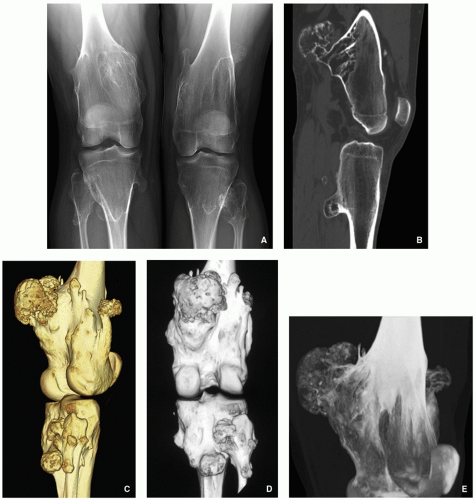

Multiple Hereditary Osteochondromata (Diaphyseal Aclasis)

Autosomal dominant genetic disorder with incomplete penetrance in females.

Male predominance 2:1.

Most commonly affected sites are the knees, ankles, and shoulders.

Imaging features similar to single osteochondromas, but lesions more commonly of sessile type (Figs. 3.47, 3.48, 3.49, 3.50, 3.51 and 3.52).

Growth disturbance (dysplastic changes, retardation of longitudinal bone growth) (Figs. 3.48, 3.49, 3.50, and 3.53).

Histopathologic features identical to those of solitary lesions.

Genetic defect has recently been identified, a novel mutation in genes EXT1 that maps to chromosome 8q24.1, EXT2 that maps to chromosome 11p11-p12, and EXT3 that maps to the short arm of chromosome 19.

Chondroblastoma

Definition:

Benign, cartilage-producing neoplasm usually arising in the epiphyses of long bones of skeletally immature patients.

Epidemiology:

Accounts for less than 1% of primary bone tumors.

Most common between 10 and 25 years of age.

Male predominance.

Patients with skull and temporal bone involvement tend to present at an older age (40 to 50 years).

Sites of Involvement:

Mostly involve epiphyses of the distal and proximal femur, followed by the proximal tibia and proximal humerus.

Patients with tumors arising in the flat bones, vertebrae, and short tubular bones tend to be older and skeletally mature, although rare cases have been reported in children.

Clinical Findings:

Majority of patients complain of localized pain, often mild, but sometimes of many years’ duration.

Soft-tissue swelling, joint stiffness and limitation, and limp are reported less commonly.

Minority of patients may develop joint effusion, especially around the knee.

Imaging:

Typically radiolucent, centrally or eccentrically located, relatively small lesion (3 to 6 cm), occupying less than one-half of the epiphysis (Fig. 3.54).

Matrix calcifications are only visible in about one-third of patients.

Periosteal reaction remote from the tumor (see Figs. 3.56A and 3.57A).

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

Gritty and grayish white mass with areas of hemorrhage.

Histopathology:

Densely cellular tissue composed of an admixture of mononuclear chondroblasts and multinucleated osteoclast-type giant cells (Fig. 3.59A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree