Chapter 38 Cervical Discography/Disc Access

Note: Please see page ii for a list of anatomical terms/abbreviations used in this book.

Cervical discography was first described in the literature by Ralph Cloward and George Smith in the late 1950s.1–4 Cervical provocation discography potentially provides a method to obtain pain-generation data with regard to the intervertebral disc.5 Most importantly, data collection includes pain provocation (i.e., none, discordant, or concordant) correlated with the patient’s clinical scenario. Also, it includes contrast volumes and disc architecture (nucleogram, post-disco CT). However, the disc architecture is less useful for cervical discography than for lumbar discography. This is based on the normal anatomy of the disc beyond the second and third decades of life.5,6 During the first and second decades of life, lateral tears may normally occur in the anulus fibrosis before complete ossification. These lateral tears and uncinate fissures may result in the complete transverse splitting of the disc. As a result, the visualization of the “normal” nucleogram may be uncommon. Analgesic response is not typically part of the standard cervical protocol, and it has not been readily studied.7,8

Over the last 60 years, the usefulness of discography has been closely examined. In this chapter, the scope of the content will not delve into this potential controversy, but the debate does continue through today. When performing discography, the final needle-tip target is the nucleus pulposus, which is the geometric center of the disc. As compared with the lumbar intervertebral disc, the position of the nucleus pulposus is slightly more anterior in location. This chapter will describe an extradural oblique technique for efficiently and safely accessing the disc via a single-needle technique. With this technique, there is potentially less necessity for displacement of the great vessels than the traditional right anterior approach. Correlation with MR or CT imaging may be beneficial. The recommended needle gauge is 25 for intradiscal entry, and the needle tip can be modified as described in Chapter 2 to optimize needle navigation.

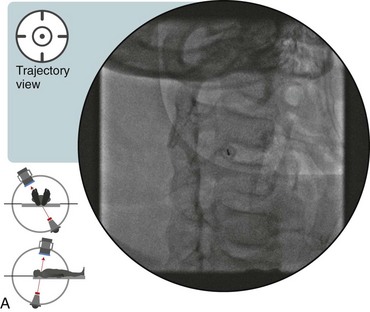

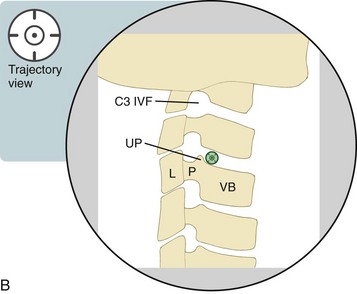

Trajectory View (Figure 38–1)

Trajectory View (Figure 38–1)

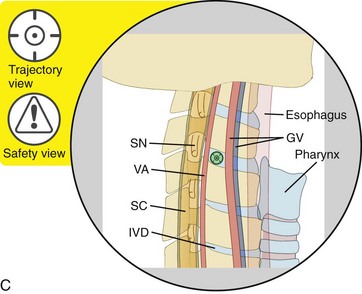

![]() Trajectory View Safety Considerations

Trajectory View Safety Considerations

Avoid the spinal nerve (SN), vertebral artery (VA), and spinal cord (SC) by remaining anterior to the uncinate process.

Avoid the spinal nerve (SN), vertebral artery (VA), and spinal cord (SC) by remaining anterior to the uncinate process.

Avoid the great vessels (GV), esophagus, and pharynx/trachea by remaining far lateral.

Avoid the great vessels (GV), esophagus, and pharynx/trachea by remaining far lateral.

The C7-T1 level may not be accessible, depending on the neck anatomy of each individual patient (i.e., a long neck versus a short neck).

The C7-T1 level may not be accessible, depending on the neck anatomy of each individual patient (i.e., a long neck versus a short neck).

Before using a needle to puncture the skin, palpate the neck to confirm that needle advancement through the skin is not directly over a palpable blood vessel (i.e., an area with a pulse).

Before using a needle to puncture the skin, palpate the neck to confirm that needle advancement through the skin is not directly over a palpable blood vessel (i.e., an area with a pulse).

![]() Notes on Positioning in the Trajectory View

Notes on Positioning in the Trajectory View

Setup is adjusted for each individual level.

Setup is adjusted for each individual level.

Enter from the right side of the neck, because the esophagus lies to the left in the lower neck.

Enter from the right side of the neck, because the esophagus lies to the left in the lower neck.

You may need to displace the great vessels laterally with your index finger.

You may need to displace the great vessels laterally with your index finger.

Upon needle entry into the disc, the initial needle-tip trajectory should be medial.

Upon needle entry into the disc, the initial needle-tip trajectory should be medial.

Confirm the level (with the posteroanterior view).

Oblique the fluoroscope to the right.

The target needle destination is immediately anterior to the junction of the uncinate process and the vertebral body.

The target needle destination is immediately anterior to the junction of the uncinate process and the vertebral body.

The degree of angulation is similar to the trajectory view for a cervical transforaminal epidural.

The degree of angulation is similar to the trajectory view for a cervical transforaminal epidural.

Place a pillow under the patient’s neck and right scapula region to achieve 5 to 10 degrees of neck extension and leftward rotation.

Place a pillow under the patient’s neck and right scapula region to achieve 5 to 10 degrees of neck extension and leftward rotation.

Count down from the C2-C3 level to ensure the proper identification of levels.

Count down from the C2-C3 level to ensure the proper identification of levels.

Tilt the fluoroscope’s image intensifier cephalad or caudad.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree