Fig. 10.1

Long 12 mm bladeless trocar used as camera port in obese patients

During the operation, obese patients can have extra adipose deposition in the posterior plane, making isolation of the seminal vesicles and vasa time-consuming. Opening the peritoneum widely here and judicious use of the assistant and fourth arm in this area is helpful. In cases with large amounts of fat and limited working space, the decision to drop the bladder and access the adnexal structures after incision of the bladder neck (anterior approach) may be time saving. Extensive periprostatic fat can complicate the incision of the endopelvic fascia and exposure of the dorsal vein. We meticulously release all this fat, especially at the apex, prior to incising the endopelvic fascia such that ideal visualization of these structures can be achieved (Fig. 10.2). Occasionally excessive bladder fat or even mesenteric fat can push towards the prostate and obscure the surgical field. In this case, either the fourth arm or the assistant can aid with retraction. Additionally, while in non-obese patients a single camera angle (typically 0° lens) is adequate, the surgeon should not hesitate to change lens angles if need be to assist in visualization during certain parts of the procedure. For example a 30° down lens may be helpful during posterior bladder neck dissection. In our experience, the remainder of the procedure is relatively unaffected by the patients weight. As these patients often have narrow pelves, ample urethral length with a watertight tension-free anastomosis should be the goal. Should the shaft of the robotic instruments be clashing with the pelvis (particularly during the anastomosis), the bedside assistant can clutch the arm and move it into a more favorable position under direct vision of the surgical field while taking care to avoid any injury to adjacent organs.

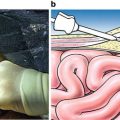

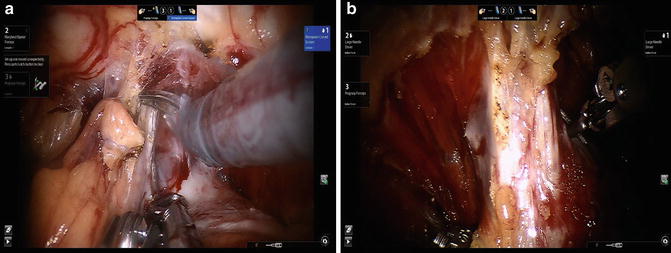

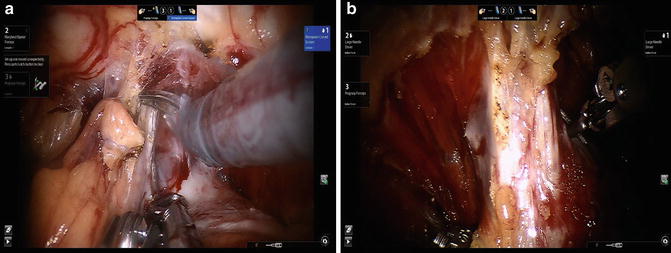

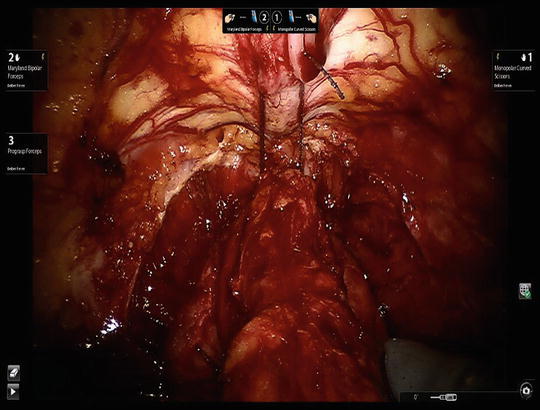

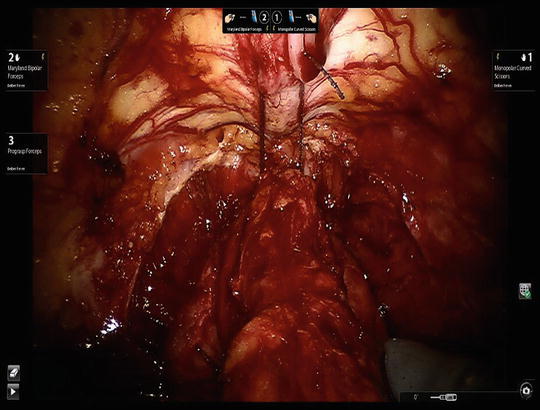

Fig. 10.2

(a) Meticulous removal of apical fat allows significantly improved visualization of the apex (b) in an obese patient with a large gland

Large Prostate

Patients with large prostates can cause a formidable challenge to the robotic surgeon due to decreased working space, impaired ability to retract the prostate to facilitate neurovascular bundle and pedicle exposure, and risk of violating the prostatic capsule during dissection. Existing literature regarding outcomes for large-gland RALP support its utilization and demonstrate feasibility. These studies have consistently documented higher operative times, slightly higher blood loss and lower positive margin rates in patients with glands >60 g compared with small or normal sized glands (Table 10.1) [12–15]. Long-term functional outcomes in this group have not been well characterized; however, there has been a suggestion of prolonged urinary incontinence in this group, most likely due to preexisting bladder dysfunction.

Bladder Neck Identification and Transection

In patients with known large prostates, we prefer the posterior approach where the vasa and seminal vesicles are dissected and the prostate is freed off the rectum early in the case. The bladder neck dissection is notoriously difficult in these patients and having these structures pre-dissected simplifies this step.

The primary technical consideration in patients with large glands relates to the potential for significantly redundant bladder necks requiring reconstruction. In order to prevent this, we spend ample time making a precise determination of the prostatovesical junction prior to division. This can be facilitated by multiple maneuvers. The Foley catheter can be manipulated to see the site of balloon entrapment. Lateral displacement of the Foley catheter during this maneuver suggests a median lobe (see following section). Additionally, the bladder neck can be pinched by the robotic instruments on either side to trap the prostate. In this way the junction can be “palpated” when the prostate feels like it gives way into the bladder (Fig. 10.3). Lastly, the lateral contour of the prostate can be followed to the midline, where the transition from prostatic to perivesical fat signals the end of the bladder and start of the prostate.

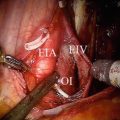

Fig. 10.3

Method of bladder neck identification using “palpation” of the prostatovesical junction

Once the anterior bladder neck is incised, the catheter is visualized, pulled back and towards the anterior abdominal wall by the surgeon’s fourth arm or assistant. The posterior bladder neck is visualized and incised. In larger prostates changing to a 30° down lens can help better orient the surgeon during this step. Once the posterior mucosa has been incised through and through, it is grasped by the surgeon and retracted cephalad. The plane between the bladder and the prostate is entered. Care must be taken to avoid incising back towards the surgeon, which may result in “button-holing” of the bladder trigone close to the ureteral orifices. Expression of cloudy fluid usually suggests caudal deviation and entry into the prostate. Thin clear fibers signal entry into the correct plane, under which the seminal vesicles and vasa can be found. These are brought through the opening (if initially dissected at the start of the operation), retracted superiorly, and pedicle ligation and nerve dissection are performed in the standard manner.

Bladder Neck Reconstruction

An excessively large bladder neck can be tailored using a variety of techniques. If the ureteral orifices are far, we perform an anterior tennis racket repair. The bladder and urethra are brought together posteriorly per routine. As the anastomosis proceeds anteriorly, a separate suture is used to close the bladder anteriorly. Most of the time a single figure-of-eight stitch is all that is needed, but occasionally a longer suture line is required. The anastomosis is then completed.

If the ureteral orifices are close, we internalize them and tailor the bladder neck by the placement of a figure-of-eight closure stitch on each side of the bladder neck. At this point a routine anastomosis can be initiated and completed. The ureteral orifices are now internalized and thus not directly involved in the anastomosis.

Management of Median Lobe

Median lobes are more common in large prostates, and have an incidence of roughly 10–20 % based on intraoperative RALP documentation [16, 17]. Similar to large prostates, the main concern with this clinical scenario lies in the potential to lose the true anatomy of the bladder neck during posterior bladder neck division and potentially injure the ureteral orifices. Although preoperative cystoscopy, cross-sectional imaging or transrectal ultrasound can all identify this variant, we do not believe this should alter the initial approach to the bladder neck and thus do not perform these procedures routinely preoperatively. A Foley balloon deviated off the midline or poor catheter drainage of the bladder can tip off the surgeon to a median lobe. Regardless, we utilize the same approach to the bladder neck as previously mentioned. If a median lobe is suspected, the bladder can be entered slightly more cranially to fully visualize the lobe. Once the catheter is identified and pulled up, a 2-0-polysorb suture is placed in a figure-of-eight fashion through the anterior part of the median lobe. If the median lobe is small it can be grasped with the fourth arm directly without an additional suture. The catheter is released and the fourth arm is used to hold this suture (or median lobe directly) and retract it towards the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 10.4). This allows adequate inspection of the posterior bladder neck and identification of the plane between the adenoma and the trigone. Excessive bleeding during this step could indicate entry into the prostate as the plane between the adenoma and bladder is relatively avascular. Indigo carmine can be utilized if there is concern about the proximity of the ureteral orifices. This is usually not necessary, however, and once the median lobe is sufficiently elevated the posterior bladder neck dissection can proceed as previously described. Large bladder necks frequently result and can be reconstructed as previously described.

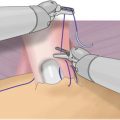

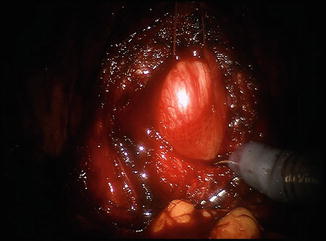

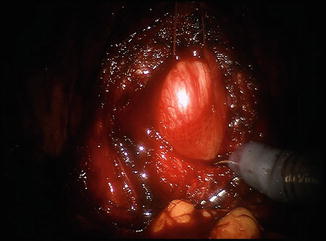

Fig. 10.4

Utilization of suture retraction of large median lobe to aid in bladder neck dissection

The published results of RALP in patients with median lobes suggest that in experienced hands, the presence of a median lobe prolongs operative time but has no impact on perioperative or functional outcomes [16–18].

Previous Bladder Outlet Surgery

Fibrosis at the bladder neck following previous surgery for BPH (Greenlight, HoLEP, TURP) can complicate RARP and cause similar bladder neck concerns as the previous clinical scenarios. Additionally, a thickened bladder wall and scarred urethra may compromise the anastomosis and increase the risk of postoperative incontinence. Unlike the case of a large prostate or median lobe, existing data suggest uniformly worse outcomes in patients undergoing minimally invasive radical prostatectomy after TURP, including higher rates of incontinence and positive surgical margins [19–21]. Given the potential for severe periprostatic inflammation following a bladder outlet procedure (especially TURP), it is advised to wait for at least 3 months prior to performing radical prostatectomy. In our experience, the inflammatory process is particularly pronounced if the prostatic capsule had been violated during the outlet procedure. The prostatovesical junction is often quite scarred and careful attention to the ureteral orifices and the lateral contour of the prostate is necessary to avoid entering an unfavorable plane. Nerve-sparing, particularly at the apex can be difficult, and typical intraoperative cues regarding cancer extent can be lost.

Prior Hernia Repair

An increasing proportion of patients with prior hernia repairs are being encountered during RALP. The use of mesh during inguinal hernia repair was once thought to be a relative contraindication for radical prostatectomy due to obliteration of the space of Retzius. This is especially worrisome with laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair, as the mesh is placed directly into the preperitoneal space and tacked to the pelvic bones. This has not proven to be the case, however, as multiple series in both the open and minimally invasive literature suggest feasibility with no difference in safety, oncologic, or functional outcomes compared to patients without hernia repair [22–24]. Adequate pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with mesh has been a recurrent concern in open and laparoscopic RP series; however, the robotic literature has not shown a difference in adequacy of lymph node yield [24]. Mesh repairs appear to elicit a greater inflammatory response and therefore have been associated with longer RALP operative times [23]. In most cases of repaired inguinal hernias, the edge of the mesh can be located lateral to the appropriate plane of dissection to drop the bladder off the anterior abdominal wall. Occasionally, bowel or bladder contents can become adherent to the fibrotic mesh and sharp dissection is needed to free these structures from the mesh. Rarely, the mesh itself needs to be incised to safely drop the bladder. If the surgeon is encountering difficulty with this step, the bladder can be filled to delineate its borders for safer dissection. If significant disruption to the hernia repair is needed to perform the prostatectomy, permanent sutures can be used to reinforce the hernia defect prior to completion of the operation. In cases of unrepaired inguinal hernias repairs, a tongue of bladder can rarely slip into the hernia sac; this must be treated with caution and the hernia sac extracted from the hernia defect as much as possible prior to ligation, otherwise an inadvertent cystotomy may result.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree