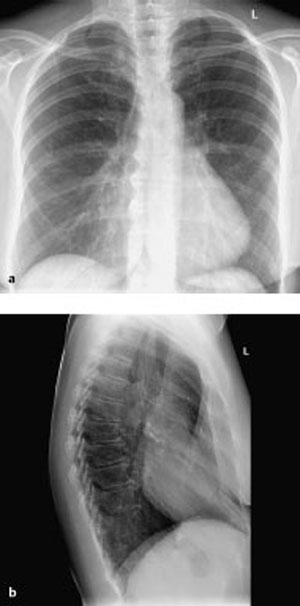

11 Chest Wall and Pleura Most common thoracic deformity. Developmental anomaly, usually clinically silent Radiographs, CT. Right paramediastinal opacity with slight leftward shift of the heart shadow so that the right margin of the heart is no longer concurrent with the right margin of the mediastinum The axial image shows marked indentation of the sternum with loss of the normal convexity of the anterior chest wall, which instead appears concave. See the radiographic and CT findings. Usually an asymptomatic incidental finding. Surgical correction is indicated where the ratio between the transverse and sagittal thoracic axes (“pectus index”) is greater than 3.25. Severity and whether surgery is indicated.

Pectus Excavatum

Definition

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Often associated with mitral valve prolapse.

Often associated with mitral valve prolapse.

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings

On the lateral film, the sternum appears significantly posterior to the anterior contour of the ribs

On the lateral film, the sternum appears significantly posterior to the anterior contour of the ribs  The retrocardiac space is significantly narrowed.

The retrocardiac space is significantly narrowed.

CT findings

CT findings

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Differential Diagnosis

Middle-lobe atelectasis | – Normal sternum |

Middle-lobe pneumonia | – Clinical aspects – Normal sternum |

Tips and Pitfalls

Can be misinterpreted as middle lobe pathology.

Selected Reference

Goretsky MJ et al. Chest wall abnormalities: pectus excavatum and pectus carinatum. Adolec Med Clin 2004; 15: 455–471

Fig. 11.1 Pectus excavatum in a 60-year-old woman. The plain chest radiograph (a) shows an opacity in the right paramediastinal lower lung field with a slight leftward shift of the heart silhouette. The contour of the heart is not concurrent with the right margin of the mediastinum. The findings suggest pectus excavatum. The lateral film (b) confirms this diagnosis.

Pneumothorax

Definition

Air in the pleural space.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Most often a sequela of trauma or biopsy  Spontaneous pneumothorax has an annual incidence of 10: 10 000.

Spontaneous pneumothorax has an annual incidence of 10: 10 000.

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Primary: Spontaneous pneumothorax  Often associated with apical bullae and hereditary connective tissue disorders (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome).

Often associated with apical bullae and hereditary connective tissue disorders (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome).

Secondary: Traumatic  Iatrogenic

Iatrogenic  Emphysema

Emphysema  Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis  Cystic lung disease (lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis)

Cystic lung disease (lymphangioleiomyomatosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis)  Parainfectious or postinfectious (Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, staphylococcal pneumonia)

Parainfectious or postinfectious (Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, staphylococcal pneumonia)  Neoplastic (metastases of osteosarcoma).

Neoplastic (metastases of osteosarcoma).

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

Plain chest radiograph (expiration film is not required).

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings

Pleural line parallel to the chest wall with a space free of pulmonary parenchyma lateral to the lung itself  Note: Typical signs can be absent in chest radiographs obtained in the supine patient

Note: Typical signs can be absent in chest radiographs obtained in the supine patient  Signs of anterior pneumothorax include a deep sulcus, unusually sharp diaphragmatic, cardiac, and mediastinal contours and increased transradiancy in the upper abdomen

Signs of anterior pneumothorax include a deep sulcus, unusually sharp diaphragmatic, cardiac, and mediastinal contours and increased transradiancy in the upper abdomen  Tension pneumothorax is characterized by mediastinal shift and a flattened, caudally shifted diaphragmatic dome.

Tension pneumothorax is characterized by mediastinal shift and a flattened, caudally shifted diaphragmatic dome.

CT findings

CT findings

Directly visualizes the air-filled pleural space  Even anterior pneumothorax is readily demonstrated.

Even anterior pneumothorax is readily demonstrated.

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

Pleural line with a space free of pulmonary parenchyma.

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Sudden chest pain (90% of cases) and dyspnea (80%).

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

Drainage  Bullectomy or pleurodesis may be indicated to treat recurrent pneumothorax

Bullectomy or pleurodesis may be indicated to treat recurrent pneumothorax  Tension pneumothorax and recurrent pneumothorax require treatment

Tension pneumothorax and recurrent pneumothorax require treatment  Treatment is advisable in pneumothorax exceeding 25% of the volume of the hemithorax or about 500 mL.

Treatment is advisable in pneumothorax exceeding 25% of the volume of the hemithorax or about 500 mL.

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

Usually good.

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Demonstrate lesion  Extent.

Extent.

Fig. 11.2 Spontaneous pneumothorax in a 17-year-old boy. The plain chest radiograph shows a mantle of avascular space around the left lung, bordered by a medial pleural line. The paramediastinal portion of the lung creates an unusually sharp contour of the aortic knob.

Fig. 11.3 Tension pneumothorax in a 27-year-old man. CT shows severe, mantlelike pneumothorax in the right lung with midline shift to the left and a flattened and displaced right diaphragmatic dome.

Differential Diagnosis

Bullous emphysema | – CT is recommended to differentiate this from encapsulated pneumothorax |

Artifact, skin or drape fold | – Mach effect (either stopping short of or entering the pleural space) that mimics a pleural line |

Tips and Pitfalls

False-negative or–positive findings.

Selected Reference

Seow A et al. Comparison of upright inspiratory and expiratory chest radiographs for detecting pneumothoraces. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 166: 313

Wintermark M, Duvoisin B, Schnyder P. Trauma of the pleura. In: Schnyder P, Wintermark M (eds.). Radiology of blunt trauma of the chest. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2000: 57–70

Pleural Effusion

Definition

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

Common causes include increased hydrostatic pressure (heart failure), reduced plasma osmotic pressure (in cirrhosis of the liver, nephrotic syndrome, renal insufficiency), infection, pneumonia  Less common causes include tumors, transdiaphragmatic passage of ascites, and collagen diseases.

Less common causes include tumors, transdiaphragmatic passage of ascites, and collagen diseases.

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Etiology, pathophysiology, pathogenesis

Transudate: Increased hydrostatic capillary pressure or reduced plasma osmotic pressure, protein concentration of 1.5–2.5g/dL  Exudate: Increased capillary permeability (inflammatory or neoplastic), protein concentration > 3g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase > 200 IU, protein concentration ratio of pleural fluid to serum > 0.5, lactate dehydrogenase in pleural fluid ≥ 2/3 of serum lactate dehydrogenase.

Exudate: Increased capillary permeability (inflammatory or neoplastic), protein concentration > 3g/dL, lactate dehydrogenase > 200 IU, protein concentration ratio of pleural fluid to serum > 0.5, lactate dehydrogenase in pleural fluid ≥ 2/3 of serum lactate dehydrogenase.

Imaging Signs

Modality of choice

Modality of choice

Ultrasound, plain chest radiographs.

Ultrasound findings

Ultrasound findings

Anechoic or hypoechoic band posterior to the chest wall demarcated by hyper-echoic visceral pleura, which contrasts against the lung  Echo inhomogeneities, septa, and pleural thickening suggest an exudate.

Echo inhomogeneities, septa, and pleural thickening suggest an exudate.

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings

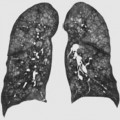

Findings depend on the extent of the effusion and patient position (erect or supine)  With increased volume of effusion there is rounding of the costophrenic angles

With increased volume of effusion there is rounding of the costophrenic angles  Lateralization of the diaphragmatic dome in subpulmonary effusion, distance between the gastric air bubble and base of the lung > 1.5 cm

Lateralization of the diaphragmatic dome in subpulmonary effusion, distance between the gastric air bubble and base of the lung > 1.5 cm  Obliteration of the diaphragmatic contour and loss of retrodiaphragmatic vascularity

Obliteration of the diaphragmatic contour and loss of retrodiaphragmatic vascularity  Basal shadow with meniscus sign

Basal shadow with meniscus sign  Hemithorax shadow with mediastinal shift

Hemithorax shadow with mediastinal shift  With the patient supine: Reduced transparency of the hemithorax and apical cap.

With the patient supine: Reduced transparency of the hemithorax and apical cap.

CT findings

CT findings

Effusion initially accumulates in the posterior pleural recess  Several signs distinguish pleural effusion from abdominal fluid—diaphragm sign (pleural fluid lies outside the diaphragmatic contour)

Several signs distinguish pleural effusion from abdominal fluid—diaphragm sign (pleural fluid lies outside the diaphragmatic contour)  Interface sign (fluid is sharply demarcated from liver or spleen in ascites)

Interface sign (fluid is sharply demarcated from liver or spleen in ascites)  Displaced crus sign (pleural effusion displaces the diaphragmatic crus cranially and anteriorly)

Displaced crus sign (pleural effusion displaces the diaphragmatic crus cranially and anteriorly)  Bare area sign (ascites separates the liver from the diaphragm only as far as the coronary ligaments).

Bare area sign (ascites separates the liver from the diaphragm only as far as the coronary ligaments).

Pathognomonic findings

Pathognomonic findings

See “Radiographic findings.”

Fig. 11.4 Massive pleural effusion on the right side in a 60-year-old man. The plain chest radiograph shows a full, homogeneously dense shadow in the right lower half of the chest. The lateral portion of the shadow rises like a meniscus, extending here to the minor interlobar fissure.

Clinical Aspects

Typical presentation

Typical presentation

Dyspnea depending on the volume of effusion and the underlying disorder.

Therapeutic options

Therapeutic options

Depend on the underlying disorder.

Course and prognosis

Course and prognosis

Depend on the underlying disorder.

What does the clinician want to know?

What does the clinician want to know?

Etiology  Drainage of encapsulated fluid accumulations.

Drainage of encapsulated fluid accumulations.

Differential Diagnosis

Malignant pleural effusion | – Often massive – Unilateral – Nodular pleural thickening in pleural metastases – Positive cytology |

| Tuberculous pleural effusion | – Protein-rich (75g/dL) – High lymphocyte content (> 70%) – Positive culture in only 25% of cases |

Empyema | – Enhancement of visceral and parietal pleura – Split pleura sign |

| Collagen diseases | – Especially systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener granulomatosis, rheumatoid arthritis |

| Chylothorax | – Density is 0 HU or less – Most common cause is trauma or lymphoma |

Tips and Pitfalls

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree