Study

Patients

Age-gender

Primary tumor

Sacral level

Adjuvant treatments

Procedure/margins

Survival

Bergh et al. [4] (2001)

11

N/A

CS (high proportion of grade 2 and grade 3 CS)

N/A

N/A

None (4 cases)

DWD (8 cases)

Resection (2)

NED (2 cases)

Ext Hemipelvectomy (4)

NEDLR (1 case)

Sacrectomy (1)a

Fourney et al. [5] (2005)

1

39M

CS

L5–S1

None

Resection/W

DWD 33 months

1

37M

CS

Hemisacrum

None

Ext Hemipelvectomy/M

AWD 78 months

1

59M

CS

Hemisacrum + SIJ

None

Resection/M

AWD 65 months

Hsieh et al. [6] (2009)

1

46F

CS

N/A

None

Resection/M

NED 32 months

Chan et al. [7] (2014)

1

62M

Well-differentiated CS

S1–S5

Rxt

Debulking/IL

NED 1.5 years

Possover et al. [8] (2014)

1

33F

Grade I CS

L5–S3 + SIJ

None

Resection/Wb

NED 17 months

Li et al. [9] (2014)

1

46F

CS

N/A

None

Hemisacrectomy/W

AWD 25 months

1

35F

CS

N/A

None

Hemisacrectomy/W

NED 29 months

1

51M

CS

N/A

None

Hemisacrectomy/M

DWD 21 months

1

38F

CS

N/A

None

Hemisacrectomy/M

NED 23 months

1

42M

CS

N/A

None

Hemisacrectomy/W

NED 69 months

Zang et al. [10] (2015)

1

43F

CS

S1–S3

None

Debulking/IL

NED 29 months

19.2 Epidemiology, Presentation, and Diagnosis

CS predominantly arises in elderly patients (range, 30–70 years) with a peak incidence in the sixth decade [14]. CSs can occur in all bones, but rarely involve the spine: the prevalence is reported between 6.5 and 12% in the mobile spine and approximately 2–5% within the sacrum [3, 4, 15–17]. Considering only the spine, roughly 19–20% of CSs arise in the cervical spine, 30–48% in the thoracic spine, 20–33% in the lumbar spine, and 16–20% in the sacrum [4, 15, 18].

Primary CS is usually eccentric and involves the proximal part of the sacrum, destroying the sacroiliac joint [4, 5]. Secondary CS can develop from benign lesions most frequently in diffuse disease such as enchondromatosis, Maffuci syndrome, or Ollier’s disease [19].

Clinical occurrence of CS varies widely. Tumor remains clinically silent for a long time before the patients finally experience pain in the area of the lesion, or pain can be present for weeks to years. Swelling and sacral mass at presentation, as well as neurological symptoms, are associated with large tumors. Radicular symptoms are seen in roughly 24% of patients [18]. In huge tumors, skin ulceration and hemoserous discharge may be observed [7].

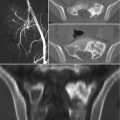

19.3 Imaging

An adequate staging of sacral CS includes complete imaging assessment and histologic evaluation. CS presents radiographically as a mixed lytic with typical dense areas of calcifications in the extraosseous soft tissue component of the tumor [20, 21]. CT scan and MRI show the same appearance of CS of the extremities. Additional imaging studies include a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone scan could be useful in distinguishing central to peripheral CS [21] as well as for early diagnosis of silent lesions in the rest of the spinal column. The appropriate imaging studies allow for a better understanding of the extent of the lesion as well as a differential diagnosis, but biopsy is a key diagnostic method for sacral CS and should be carefully planned according to the definitive surgery.

19.4 Pathology

Histologically, CSs show abundant blue-gray cartilage matrix production and irregularly shaped cartilage lobules varying in size and shape. These lobules may be separated by fibrous bands or permeate bony trabeculae. Mitotic figures, hypercellularity, mild to moderate nuclear atypia, double-nucleated cells, and myxoid changes in the stroma can be observed [15, 16, 19, 20, 22]. CSs are pathologically classified as conventional (80–85%), clear cell (1–2%), myxoid (8–10%), mesenchymal (3–10%), and dedifferentiated (5–10%) subtype [19, 22]. Moreover, they are grade on a scale of 1 (low grade) to 3 (high grade) based on nuclear size, nuclear staining, and cellularity [22, 23].

19.5 Treatment

Sacral CSs are rare and thus difficult to manage. In general, surgery is the most accredited treatment modality, as no chemotherapy has been demonstrated to be effective against CS as well as conventional radiotherapy [5, 6, 15, 16, 18]. Resection with wide margins is the procedure of choice in sacral CS, since this is the most effective way of reducing recurrence rate [6].

19.5.1 Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment consisting of either curettage (debulking procedures) or en bloc resection has been described for both primary and recurrent tumors [5, 6, 10]. Sacral tumors are often large and achieving adequate surgical margins during resection is challenging, because of difficulties in accessing the lesion, risks for damages of neighboring organs, and risks for massive blood loss due to an extensive vascularity. Moreover, CS usually involves the sacroiliac joint [9, 24]. Therefore, the surgical expertise required to remove these tumors is usually found only at centralized tumor treatment centers [4]. Nevertheless, in some cases, intralesional curettage, or debulking procedures, are more appropriate [7, 10], as well as been reported for CS of the mobile spine [25].

Results following curettage are contradictory, probably due to the different behavior of tumor in relation to histologic grade. In the mobile spine, two groups reported their large experience showing local recurrence or progression of disease in all cases treated with curettage, with poor oncologic outcome [15, 25]. York et al. found a recurrence rate of 69% and 20% in patients treated with intralesional or wide margins, respectively [18]. Good results with intralesional excision combined with radiotherapy have been reported in cases of low-grade well-differentiated chondrosarcoma [7]. Other case reports reported no evidence of disease or recurrence in patients treated intralesionally for sacral CS [10].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree