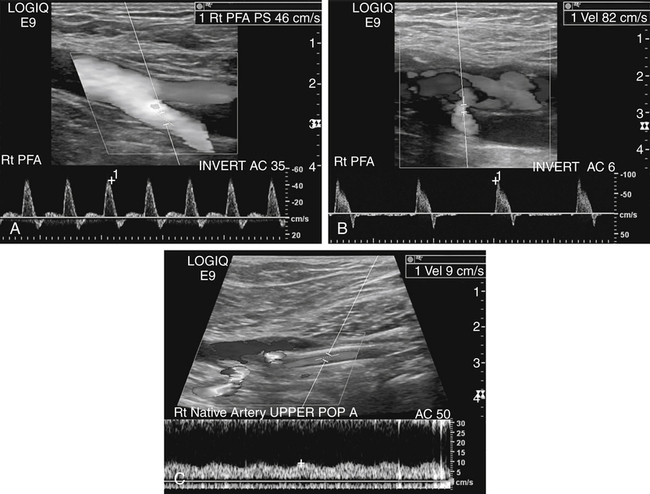

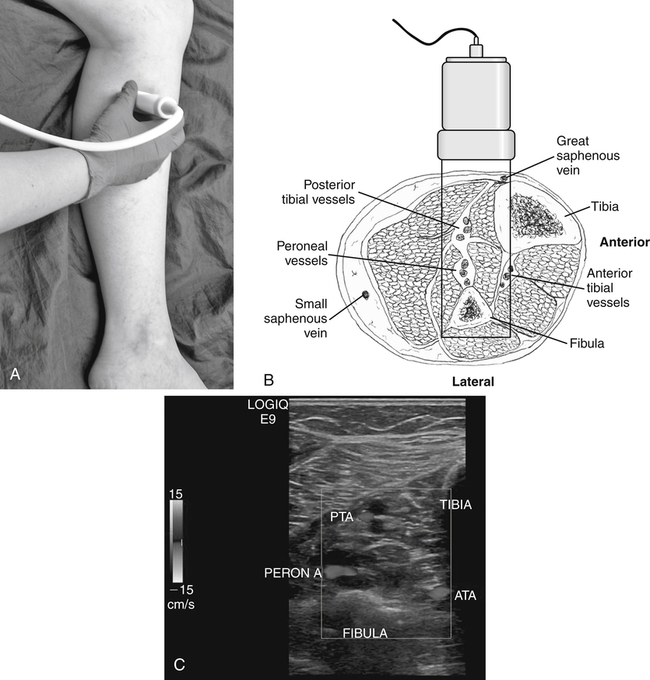

Rebecca Madery and Nicole Strissel • Identify anatomic landmarks for proper vessel identification in the calf. • Differentiate between various causes of arterial disease in the leg. • State symptoms associated with arterial disease. • Describe the duplex Doppler and indirect physiologic studies that can be used to detect arterial disease of the lower extremity. • Describe the sonographic appearance of arterial disease in the lower extremity. • Characterize Doppler waveforms associated with arterial disease. Lower extremity arteries are accompanied by a single vein or, distal to the popliteal artery, paired veins with the same name. Most of the anatomy can be well visualized on most patients with a 6 to 9 MHz linear transducer. Imaging of the distal aorta and iliac arteries requires the use of a curvilinear transducer with frequencies ranging from 3 to 6 MHz. Starting at the aortic bifurcation and working distally to the foot, a normal artery gradually tapers as it gives rise to branches until it terminates as an arteriole. The common iliac arteries originate at the level of the umbilicus from the aortic bifurcation and bifurcate into the external and internal (hypogastric) iliac arteries. The hypogastric artery branches deep into the pelvis to perfuse the sigmoid colon, rectum, and reproductive organs. The external iliac artery continues through the pelvis to become the common femoral artery at the inguinal canal, which bifurcates into the deep femoral artery (profunda) and femoral artery. At the level of the adductor canal, the femoral artery becomes the popliteal artery as it courses posterior to the knee and bifurcates into the anterior tibial artery and the tibioperoneal trunk. The anterior tibial artery branches anteriorly and laterally, passing through the space formed between the tibia and fibula then lateral to the tibial shaft where it eventually terminates on the dorsal side of the foot as the dorsalis pedis artery. The tibioperoneal trunk bifurcates into the posterior tibial artery and peroneal (fibular) artery. From a medial scanning approach, the posterior tibial artery continues more superficially than the peroneal artery, which runs deeper and lies just medial to the fibula. (Fig. 36-1; see Color Plate 55). Arteries of the ankle and foot commonly used for Doppler samples or pulses include the posterior tibial, which can be found about 1 inch posterior to the medial malleolus, and the dorsalis pedis, which is found in the anterior midfoot just over the proximal third metatarsal. Diagnostic examinations used in assessing lower limb arterial disease include physiologic nonimaging vascular studies (segmental pressures, ankle-brachial index [ABI], pulse volume recording [PVR]), sonography, computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, and angiography. To include or rule out vascular claudication as a differential diagnosis, the first examination is typically a physiologic test involving continuous wave Doppler and segmental pressures before and after exercise. Using continuous wave Doppler, the patient should have a qualitative analysis of the common femoral artery, femoral artery, popliteal artery, posterior tibial artery, and dorsalis pedis artery to determine if the blood flow is triphasic, biphasic, or monophasic in nature (Fig. 36-2). To determine the approximate level of disease, segmental pressures and/or PVR’s should be taken. Normally, the pressure gradient between adjacent cuffs, or at the same level on the contralateral extremity, does not exceed 20 mm Hg. A pressure gradient greater than 30 mm Hg is indicative of a significant obstruction between or beneath the cuffs.1 Segmental pressures are taken by measuring blood pressures from the thigh, calf, and ankle (three-cuff method) and comparing that number with the highest brachial pressure (both arms should be assessed unless contraindicated). A four-cuff method may also be used with two cuffs placed on the thigh with the awareness that the cuff closest to the groin may be artificially elevated because of the discrepancy in cuff size and thigh circumference. An ABI can be used if a quick study is necessary or for follow-up of a prior physiologic test. A normal ABI ratio generally is 0.90 to 1.40. An ABI ratio less than 0.90 is considered abnormal; however, individuals with values between 0.90 and 1.10 and greater than 1.40 may be at a slightly higher risk for disease.1 After baseline values have been obtained, the patient should exercise (at the prescribed protocol of that vascular laboratory) and the ABI measurements should be repeated. Patients presenting with a normal ABI may unmask arterial disease after exercise due to the increased demand for blood in the working extremity. The ABI should increase or remain constant in a normal extremity. If pressures decrease significantly but return within 2 to 6 minutes, single-level disease should be considered. However, a significant decrease in pressures after exercise for 10 minutes is highly suggestive of multilevel disease. Symptoms of claudication are not likely to be vascular in origin if they do not correlate with a decrease in pressures. Peripheral arterial disease is the process in which arteries become narrowed and impede blood flow to the limbs, generally the lower extremities. Arteriosclerosis is a general term describing the hardening of arterial walls and the associated loss of elasticity. Arteriosclerosis results in a reduced arterial lumen and, ultimately, decreases blood pressure and flow to the distal limb or organ. A stenosis is considered hemodynamically significant if there is a 50% reduction in diameter or a 75% reduction in cross-sectional area.2 The most common cause of arteriosclerosis is atherosclerosis (ASO). ASO is the result of increased fatty deposits (atheromatous plaque) along the arterial walls. Patients may experience various symptoms depending on the severity of the disease ranging from asymptomatic to debilitating distal ulcerations and eventual limb loss. An aneurysm is a localized bulging or focal enlargement of a vessel by approximately 50%; the popliteal artery is the most common location for a peripheral aneurysm to occur.3 The accepted measurement criterion for a popliteal artery aneurysm is 1.5 to 2.0 cm. However, because the normal popliteal artery diameter measures from 0.4 to 0.9 cm, several studies suggest that, in correlation with an increased diameter of 50%, a focal area of 1.0 cm may be considered an aneurysm if the normal arterial diameter is 0.6 cm.3 Isolated aneurysms are rare in the iliac and femoral arteries. Lower extremity aneurysms increase the patient’s risk of having an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Close monitoring is necessary as significant risks are associated with lower extremity aneurysms including: distal embolization, acute occlusion and rupture.

Claudication

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Normal Vascular Anatomy

Symptoms and Testing

Claudication

Vascular Test Findings

Arterial Disease

Atherosclerosis

Popliteal Aneurysm

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Claudication: Peripheral Arterial Disease