Chapter 2 Clinical-Anatomical Syndromes of Ischemic Infarction

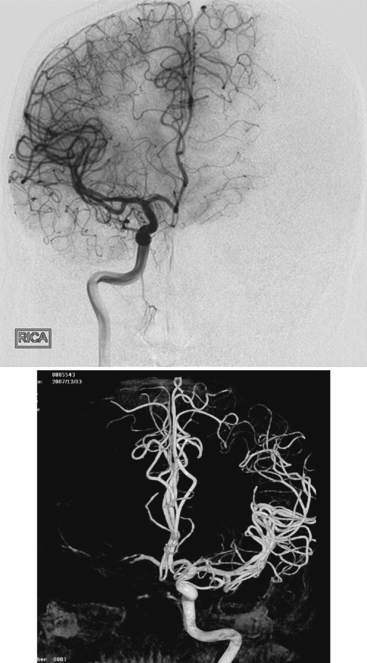

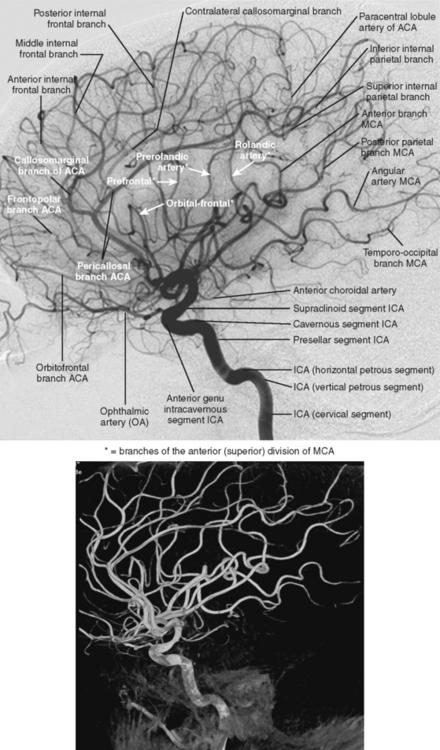

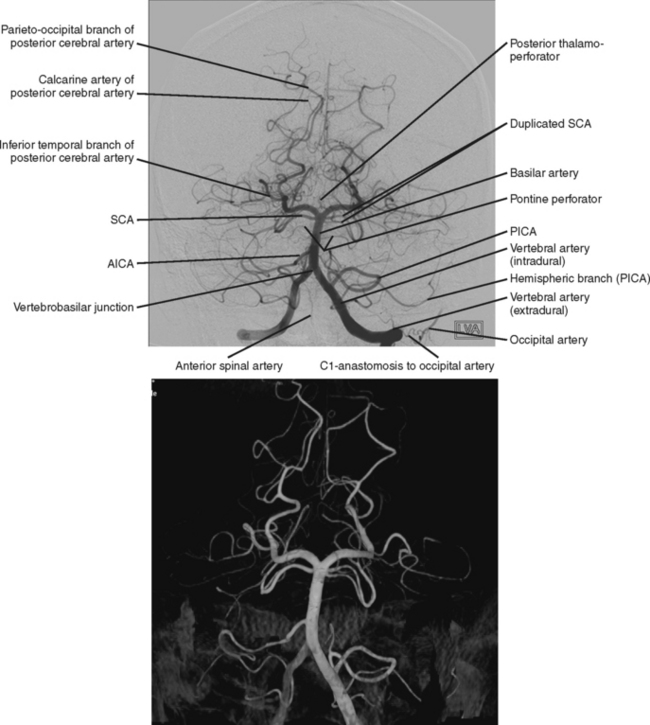

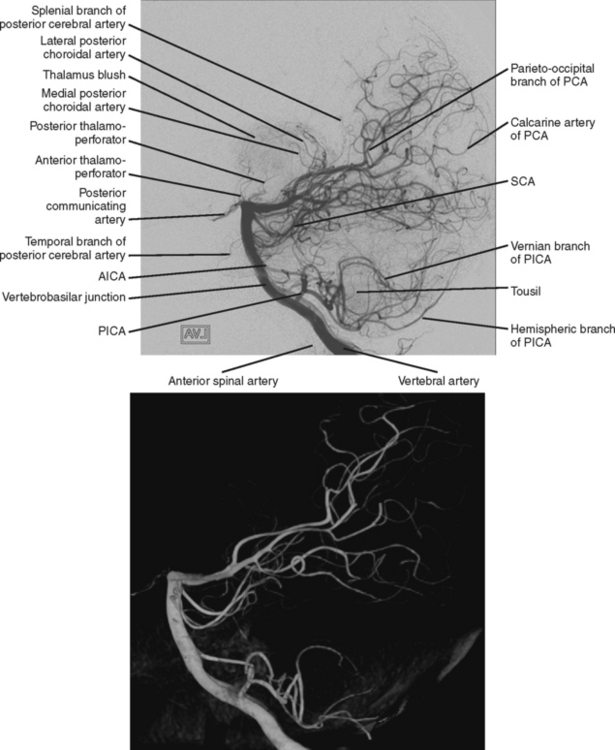

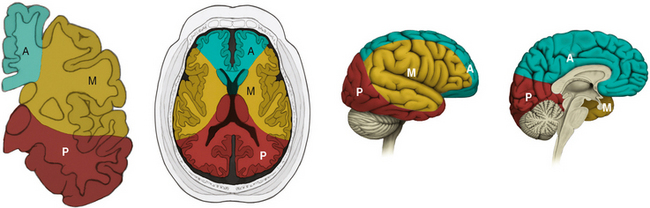

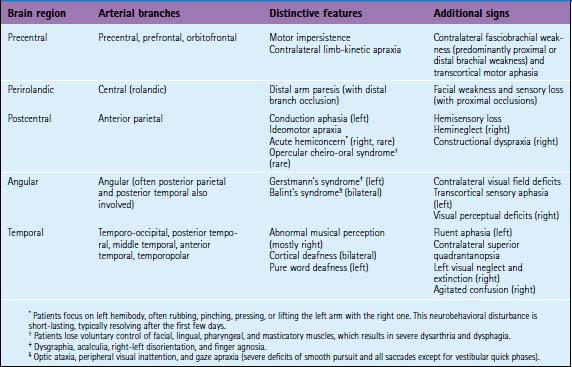

Ischemic stroke can be defined as a sudden focal neurological deficit corresponding to a vascular distribution. Brain imaging techniques allow us to visualize lesions with great anatomical precision. However, optimal interpretation of the information provided by neuroimaging requires having detailed knowledge of the arterial anatomy (Figures 2-1 through 2-4) and the vascular territories of the brain (Figure 2-5).

CAROTID BIFURCATION OCCLUSION

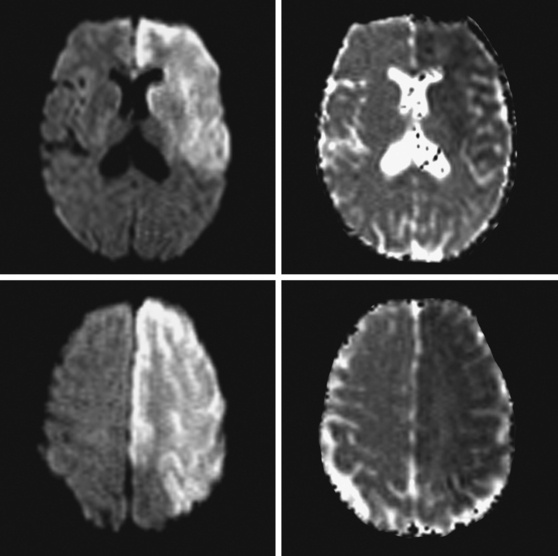

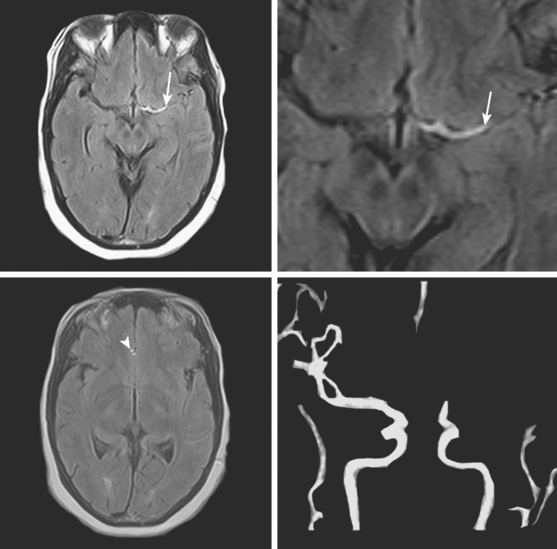

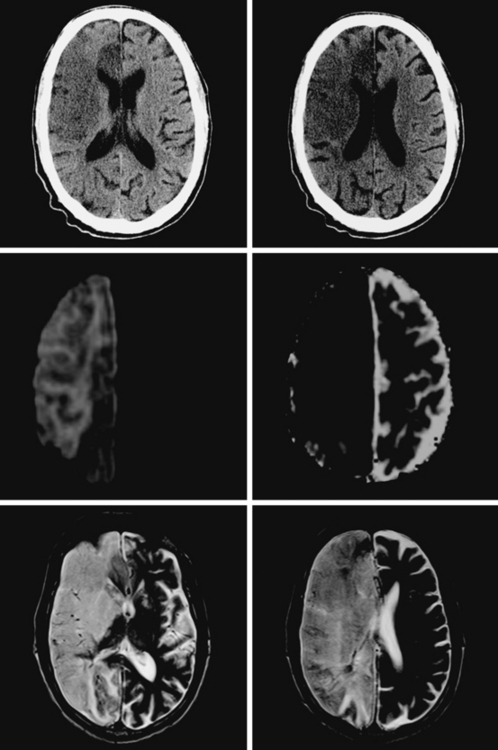

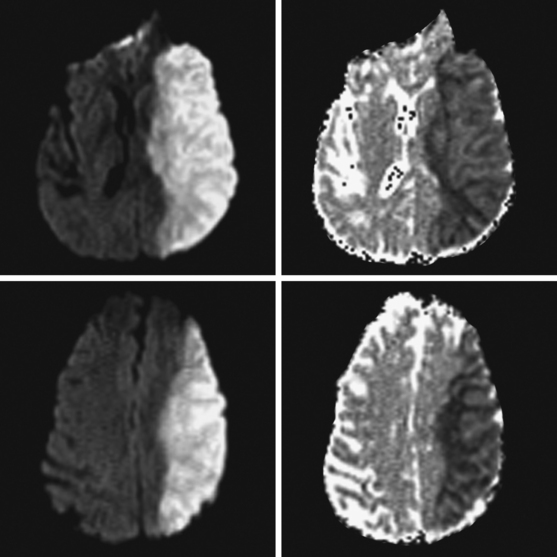

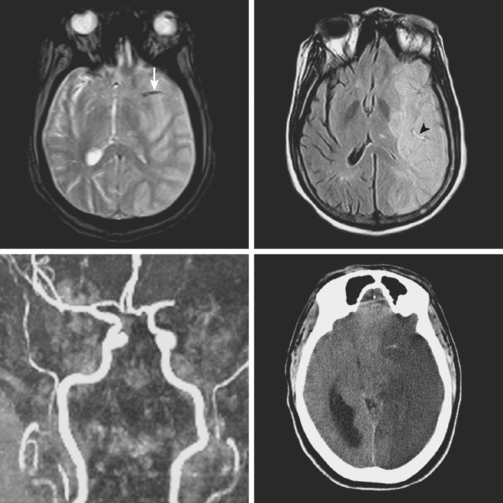

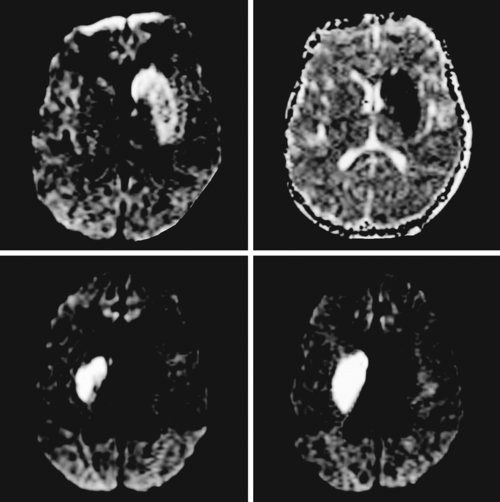

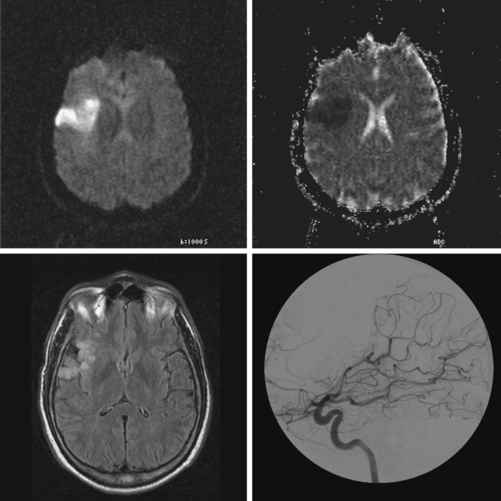

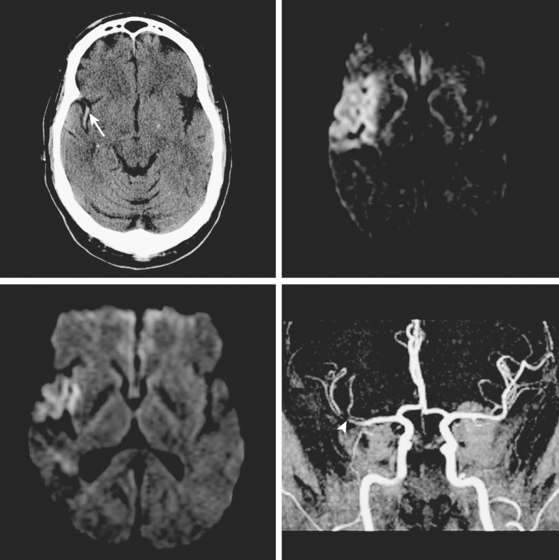

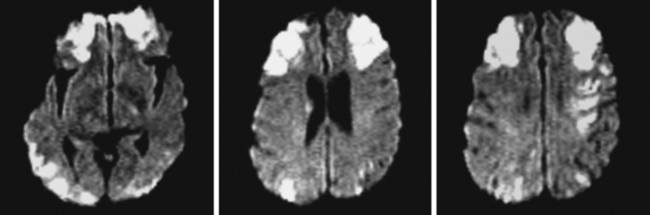

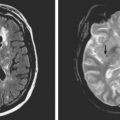

A 61-year-old man with history of coronary artery disease, previous myocardial infarction, and multiple vascular risk factors presented to the emergency department with global aphasia and right hemiplegia for more than 6 hours. On examination, he was drowsy and exhibited forced left gaze deviation, right hemianopia, right flaccid hemiplegia involving the arm and the leg to similar degree, and absent response to pain on the right side. Diffusion-weighted imagery (DWI) of the brain revealed a large area of ischemia in the left hemisphere, including the territories of the anterior and middle cerebral arteries (Figure 2-6). Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence showed no parenchymal hyperintensity but disclosed extensive hyperintense signal in the left middle cerebral artery consistent with fresh thrombus (Figure 2-7). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the intracranial circulation confirmed the presence of a left carotid terminus occlusion (Figure 2-7). The patient was subsequently diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction and a left ventricular mural thrombus. His neurological condition deteriorated over the following 48 hours, and he expired after care was restricted to palliative measures.

MIDDLE CEREBRAL ARTERY OCCLUSION

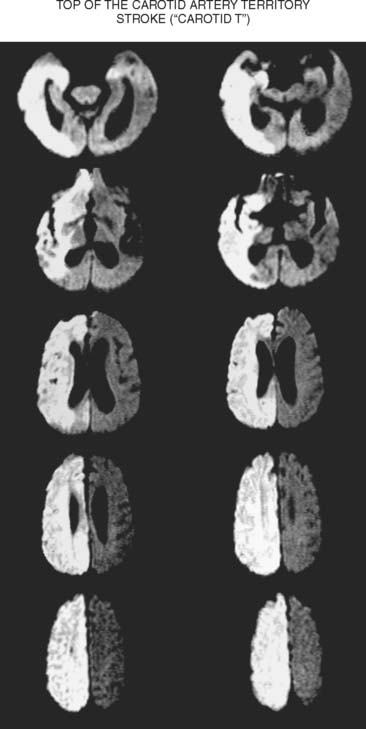

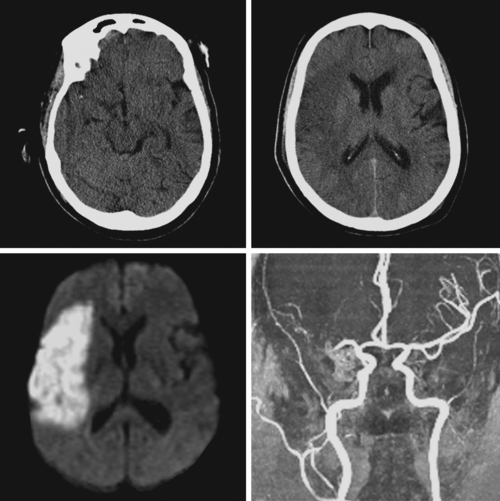

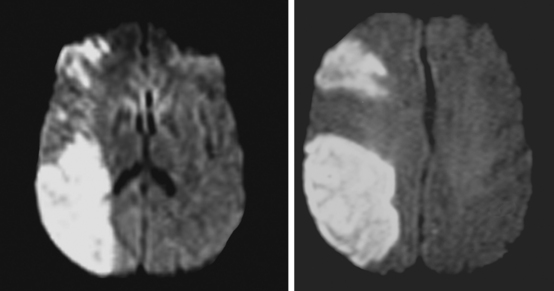

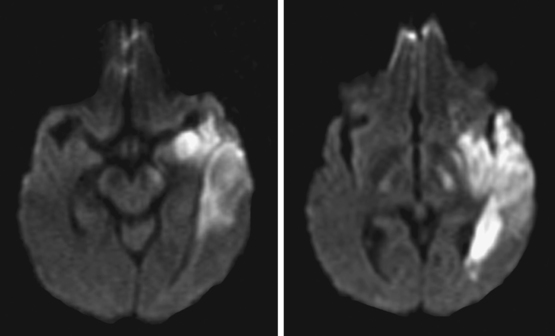

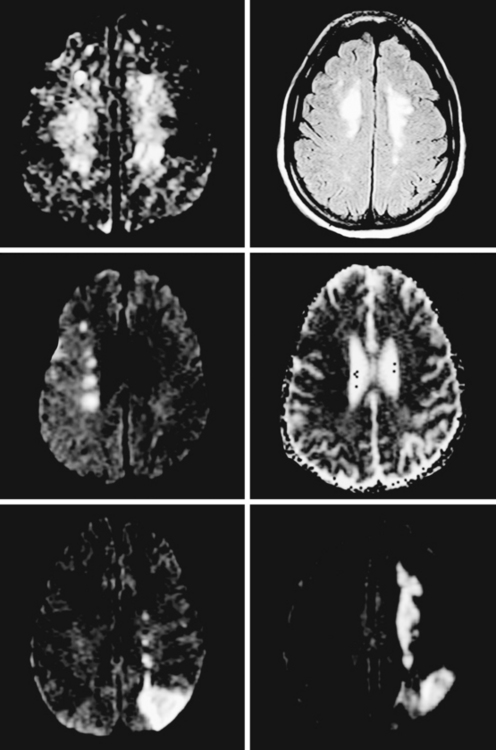

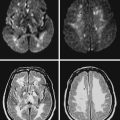

A 65-year-old man with history of hypertension presented with acute global aphasia and right flaccid hemiplegia involving the lower face, the arm, and, to a lesser degree, the leg. He also had a dense right visual field deficit and profound right sensory loss. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with DWI revealed extensive ischemia in the territory of the left MCA (Figure 2-13). T2* sequence disclosed a hypointense signal in the left MCA indicative of acute vessel thrombosis and MRA confirmed the left M1 occlusion (Figure 2-14). Atrial fibrillation was noted on cardiac telemetry. Over the following 48 hours, the patient developed fatal brain swelling (see Figure 2-14).

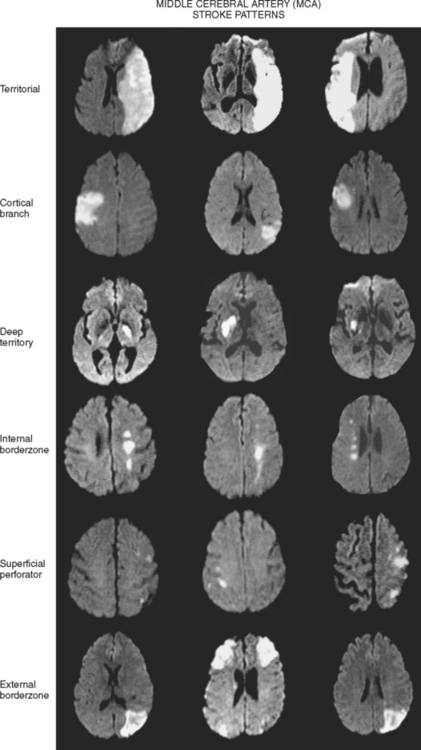

Territorial MCA Infarction

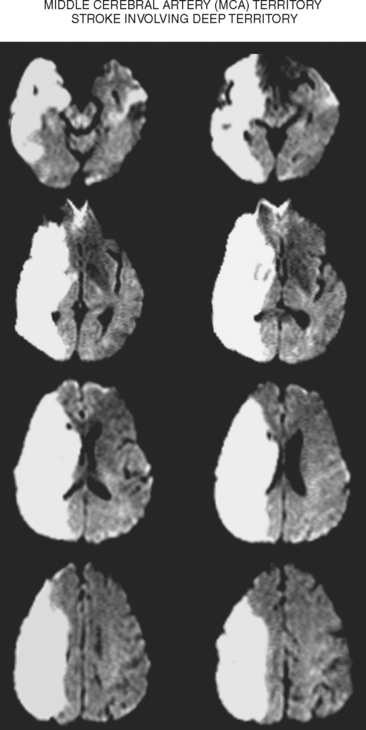

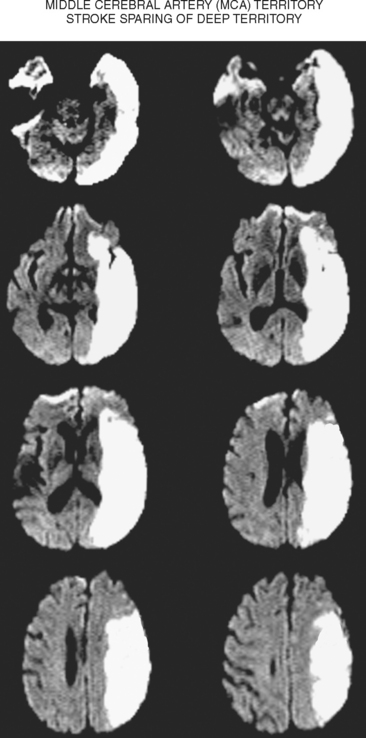

Deep Middle Cerebral Artery Infarction

Superficial Divisional Middle Cerebral Artery Infarction

Superficial Cortical Infarctions

Hemispheric Border-Zone Infarctions

ANTERIOR CEREBRAL ARTERY OCCLUSION

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree