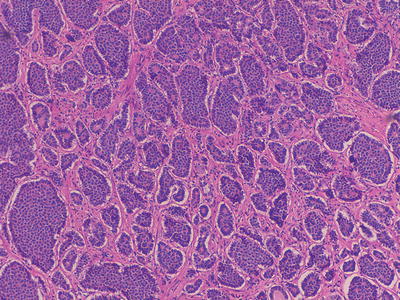

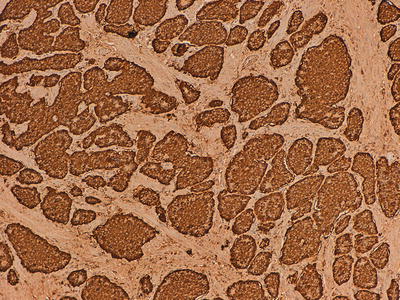

Fig. 32.1

Low power microscopic image of a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumour in the terminal ileum, showing its polypoid structure and infiltrative base into the wall of the small bowel

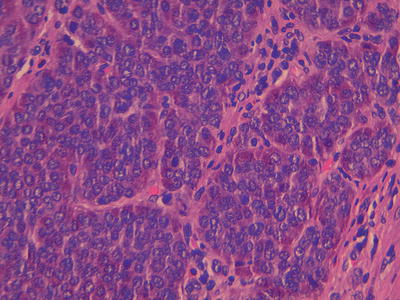

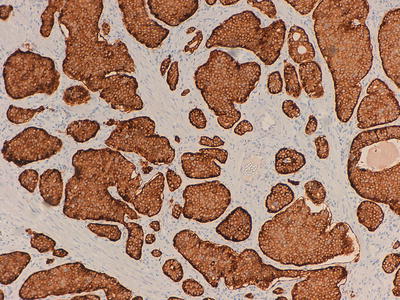

Fig. 32.2

Medium power microscopic image of a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumour in the terminal ileum

Fig. 32.3

High power image of a well differentiated neuroendocrine tumour with the classical nests of cells with stippled nuclear chromatin, within the cytoplasm there are red staining secretory granules. A single mitoses is seen in the centre of the field

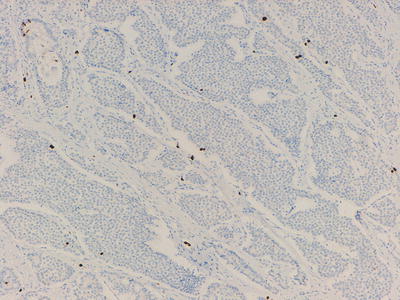

Fig. 32.4

Immunohistochemical marker for chromogranin A, a component of secretory granules

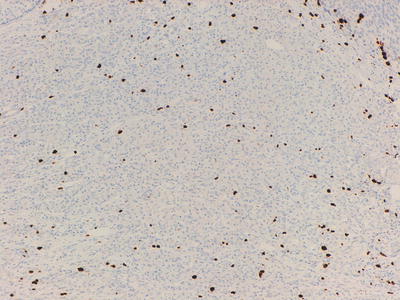

Fig. 32.5

Immunohistochemical marker for synaptophysin, a small vesicle antigen

These tumours are then graded using both the mitotic rate (mitoses per 10 high power fields) and Ki-67 proliferation index (immunohistochemical marking of proliferating cells, percentage in a sample of 2,000 cells), see Table 32.1 and Figs. 32.6, 32.7, and 32.8.

Table 32.1

NET pathological grading based on mitotic rate and Ki-67 index

|

Grade 1

|

Grade 2

|

Grade 3

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mitotic rate per 10 HPF

|

<2

|

2–20

|

>20

|

|

Ki-67 index (%) brackets are for pancreatic tumours

|

≤2 (5)

|

>2 (5) – 20

|

>20

|

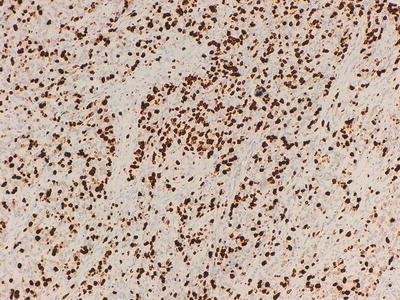

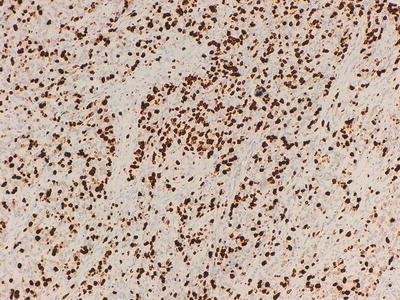

Fig. 32.6

Ki-67 labeling of cells in a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumour, <2 % of cells are highlighted (Grade 1)

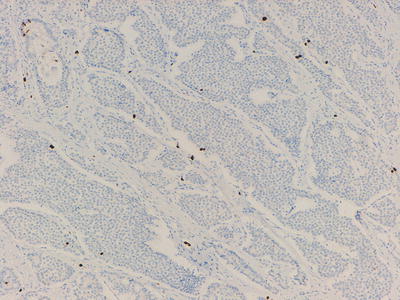

Fig. 32.7

Ki-67 labeling of cells in a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumour, >2 %, but less than 20 % of the cells are highlighted (Grade 2)

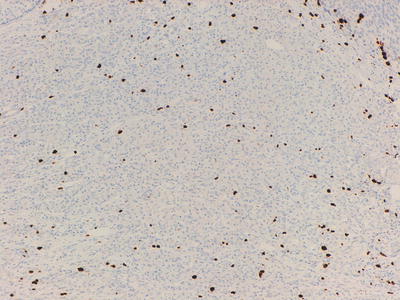

Fig. 32.8

Ki-67 labeling of cells in a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumour, >20 % of cells are highlighted (Grade 3)

At other end of the spectrum are poorly differentiated NET , which have a different histological appearance. Generally these tumours form an infiltrating tumour mass with very poorly differentiated morphology. The cells have very little cytoplasm, the nuclei are hyperchromatic, necrosis is prominent and mitoses obvious. These tumours do stain with neuroendocrine markers, but much less strongly and reliably. Ki-67 can highlight up to 100 % of the cells. These poorly differentiated NET are also what have been previously called small cell carcinoma. Although these tumours fall onto a spectrum with the well differentiated NET there are very few examples of tumours that sit in the middle of the range. There are however occasional well differentiated NET with a higher than expected Ki-67 index, that can fall into the grade 3 category, usually reserved for tumours of the poorly differentiated/small cell type.

There are occasional tumours which may have mixed exocrine-endocrine features, usually there is an obvious adenocarcinoma, which focally has areas which resemble a NET and will stain appropriately. These should generally be managed as a standard adenocarcinoma. This problem is compounded in the appendix, where goblet cell carcinoids (GCCs) occur, as these tumours also show both endocrine and adenocarcinomatous differentiation, to varying degrees. Tang has sub-classified GCC into three distinct types, with different prognoses [21].

In the lung, although much of the work on grading NET was done in this area, the terms carcinoid, atypical carcinoid and small cell carcinoma are still used. The carcinoid of the lung looks morphologically similar to that in the GI tract, with a similar immunophenotype. The differentiation from an atypical carcinoid is the presence of >2 mitoses per 10 high power fields, nuclear pleomorphism and necrosis. Similarly small cell carcinoma has the same diagnostic features as in the GI tract.

32.6 Clinical Presentation

Local symptoms are dependent on the site of the tumour. For example, patients with NET originating in the gastrointestinal tract may have symptoms including dysphagia, haematemesis, bowel obstruction or obstructive jaundice. Likewise pulmonary NET may result in dyspnoea, haemoptysis, cough and lobar collapse. Some small, non-functional tumours may be found coincidentally. However, functional NET secrete peptides which can result in the development of carcinoid syndrome. This is usually due to metastases in the liver releasing serotonin and tachykinins into the systemic circulation. Typical symptoms consist of flushing, palpitations, diarrhoea and abdominal pain [22]. In severe cases, and sometimes precipitated by anaesthetic induction, it may lead to a carcinoid crisis with life threatening bronchospasm, tachycardia and haemodynamic instability. Patients are managed by high dose octreotide and aggressive fluid resuscitation. One out of every five patients at diagnosis may develop carcinoid heart disease from endocardial thickening of the right-sided chambers. Restriction of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves commonly cause right-sided valvular defects [15, 23].

Functional GEP-NET may arise from the various endocrine glands in the digestive tract and include insulinomas, gastrinomas, VIPomas, glucagonomas, and somatostatinomas. Thus, corresponding symptoms will result from over secretion of the respective peptides. Patients with an insulinoma typically present with symptoms of low blood sugar. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome results from oversecretion of gastrin causing peptic ulcers, abdominal pain and diarrhoea [16]. VIPomas cause watery diarrhoea, hypokalaemia and dehydration. Glucagonomas may result in the development of diabetes mellitus, diarrhoea, venous thrombosis, and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Classical dermatological changes include necrolytic migratory erythema (NME) and cheilitis [24]. Somatostationomas may cause diabetes mellitus, cholelithiasis and steatorrhoea. Constitutional symptoms include anorexia, weight loss and lethargy.

32.7 Prognosis

Prognosis may vary depending on a number of factors including site of origin, stage at diagnosis and pathological grading. The 5 year survival of all patients with NET remained at 60–65 % between 1973 and 2002. The highest 5 year survival rate of 74–88 % was seen in those with rectal primaries and lowest for pancreatic primaries at 27–43 %. The typical 5 year survival for patients with locally advanced poorly differentiated NET was 38 % and 4 % with metastatic disease. Conversely, for patients with well differentiated disease the figures are 82 % and 35 % respectively [1, 2]. Thus having a primary pancreatic tumour with poorly differentiated histology and extra-hepatic metastases were considered to be negative prognostic factors [25].

32.8 Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on clinical history, measurement of biochemical markers, imaging and histological confirmation.

32.8.1 Biochemical Markers

Chromogranin A is present in chromaffin granules of neuroendocrine cells and is usually raised in NET . Concentration correlates with tumour burden [26]. 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), the main metabolite of serotonin is the breakdown product of serotonin and may be detected in urine. Measurement of HIAA may achieve a sensitivity and specificity of 73 % and 100 % respectively [27]. Furthermore, depending on the specific origin of the NET, correlating biochemical markers may be detected (Table 32.2).

Table 32.2

Specific NET and associated biochemical markers

|

Subtype

|

Raised biochemical markers

|

|---|---|

|

Insulinoma

|

Chromogranin A, insulin, blood glucose

|

|

C peptide, pro-insulin

|

|

|

Gastrinoma

|

Gastrin

|

|

Glucagonoma

|

Glucagon, enteroglucagon

|

|

VIPoma

|

VIP

|

|

Somatostatinoma

|

SOM

|

|

Pancreatic polypeptidoma

|

Pancreatic polypeptide

|

|

MEN 1

|

Chromogranin A, insulin, glucagon, pancreatic polypeptide

|

32.8.2 Imaging

For localization of the primary tumour and staging purposes multimodality imaging including the use of CT, MRI, endoscopic ultrasound, somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SSRS) and positron emission tomography (PET) may be employed [15]. SSRS involves the intravenous injection of radiolabelled somatostatin analogue. Gallium-68 labelled octreotide PET may assist the detection tumours not apparent on conventional CT [28]. Iodine-131-labelled metaiodobenzylguanidine (131I-MIBG) scintigraphy is useful for identifying tumour uptake and may also be used for therapeutic purposes.

32.9 Treatment

32.9.1 Surgery

Radical resection in localized NET is the only curative approach in patients with NET. Patients may undergo elective resection but occasionally those with bowel NET may present with acute bowel obstruction requiring emergency resection.

32.9.2 Medical Therapy

Traditionally, interferon alpha (IFNa) therapy has been used. It activates T-lymphocytes and causes apoptosis . In patients with functional NET , improvement of symptoms due to hormonal hypersecretion and tumour reponse of around 10 % have been reported [29–31]. However, a range of associated toxicities such as fatigue, headache, myalgia and depression mean that long term use may not be tolerated and its use has become less common place in current management.

Known subtypes of somatostatin receptors are SST1, SST2a, SST2b, SST3, SST4 and SST5. Somatostatin analogues include octreotide and lanreotide are commonly used, but newer generation analogues like pasireotide block a wider range of these G protein-coupled transmembrane receptors. Treatment leads to the down regulation of peptide secretion in functional tumours thus providing symptomatic improvement. Beyond its functional ability, evidence from the PROMID trial suggested an anti-proliferative effect. Eighty five patients with locally inoperable or metastatic well differentiated midgut tumors were randomized to octreotide or placebo [32]. The median time to tumour progression was found to be significantly longer with octreotide compared to placebo (14.3 vs 6 months). Benefit was seen in both functional as well as non-functional tumours. CLARINET (Lanreotide Antiproliferative Response in patients with GEP-NET ) was a large phase III randomised controlled trial assessing the effect of lanreotide on progression free survival (PFS) in non-functioning well to moderately differentiated NET. In the treated group, a significant extension of PFS was reported (HR 0.47; p = 0.0002) [33]. Side effects included pain at the injection site, anorexia, nausea, diarrhoea, lethargy and hypoglycaemia.

32.9.3 Arterial Embolisation

Systemic radionuclide therapy with 131I-MIBG is useful as a therapeutic adjunct in managing diffuse metastases demonstrating tracer uptake. Biochemical and radiological response rates reaching 40–60 % and 10–15 % respectively have been reported [34, 35]. However, repeated use may increase the risk of radiation nephritis, pancytopenia and myelodysplasia.

In patients with liver-only metastases, hepatic arterial embolization may be used alone or with infusional chemotherapy. Radioactive microspheres like yttrium-90 injected into tumour sites deliver a high concentration of therapeutic radiation with a sharp fall off which minimizes damage to normal tissue. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) under radiological guidance employs rapidly alternating electric current which generate heat leading to tumour necrosis at the target site.

32.9.4 Chemotherapy

One of the earliest trials using chemotherapy was in the 1980s showing modest tumour activity. A randomised controlled study compared 5-fluorouracil (5FU) combined with streptozocin versus doxorubicin showing similar response rates of 22 % and 21 %. However, this did not translate to any survival benefit [36]. In 1992, a randomised trial using streptozocin combined with doxorubicin reported a combined biochemical and radiological response rate of 69 % and a median survival of 26 months [37]. Follow-up investigation in 2004 compared this two drug combination with the addition of 5-fluorouracil vs triple combination with streptozocin/5-fluorouracil/cisplatin. Radiological response rate was reported at 36 %, 39 % and 38 % respectively rate with a median overall survival of 24, 37 and 32 months respectively [38].

Studies investigating capecitabine monotherapy, taxanes, topotecan, and gemcitabine have yielded response rates of between 0 % and 10 % [39–43].

Temozolamide has been used in together with other drugs with varying success. Combination of temozolomide with anti-angiogenic drugs like thalidomide and bevacizumab have reported overall response rates of 24–45 % [44, 45]. Addition of capecitabine, an oral anti-metabolite, however achieved a response rate of 70 % in a very small study [46]. Variation of tumour sensitivity to this alkylating agent could be due to the mediating effect of methylguanine DNA methyltransferase (MGMT). It is postulated that the varied expression of this regulatory protein could account for the effectiveness of the drug, and the absence of MGMT may explain the sensitivity of some tumours [47].

Combination of platinum with a topoisomerase inhibitor has shown some activity. Firstline treatment with carboplatin plus etoposide versus cisplatin plus etoposide demonstrated equivalent response rates of 30 % vs 31 %, and overall survival of 11 vs 12 months respectively [48]. However, it is postulated that tumours with Ki-67 of <55 % were less likely to respond to platinum based chemotherapy regimens [49].

32.9.5 Biological Targeted Therapy

32.9.5.1 Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) are small molecules which disrupt intracellular signalling involved in tumour growth, differentiation and progression. Sunitinib malate is a TKI with activity to receptors including VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFR-α and PDGFR-β). An initial phase II trial of 107 patients with progressive advanced NET used sunitinib at 50 mg o.d. every 4 weeks of a 6-weekly cycle [50

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree