Chapter 6

Clinical Assessments and Sonographic Procedures

Students who successfully complete this chapter will be able to do the following:

• List the major specialty sonographic examinations.

• Describe and demonstrate the patient positions commonly used in sonography.

• Discuss patient preparations for abdominal, vascular, obstetric-gynecologic, and cardiac sonography.

• Describe the basic components of the four major specialty scanning protocols.

• Identify the findings and normal values of laboratory tests related to abdominal and obstetric sonography.

3. Cardiac (adult, pediatric, fetal)

6. High-resolution (superficial structures, intraoperative techniques)

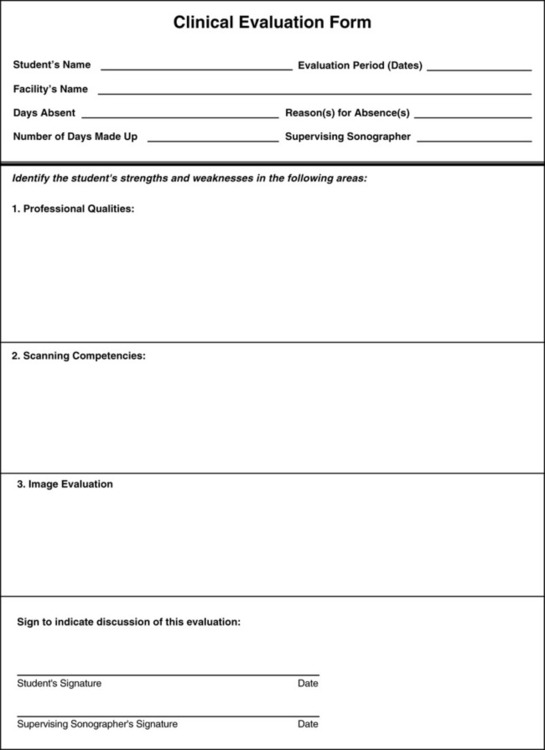

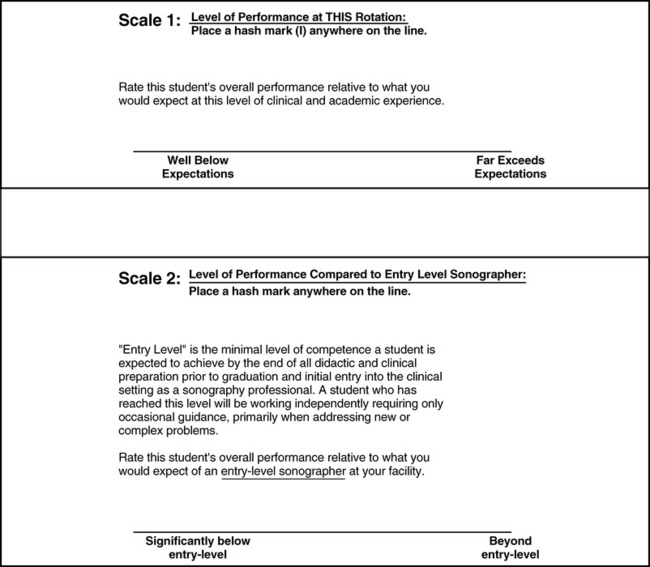

This chapter focuses on the four most widely practiced diagnostic ultrasound specialties: abdominal, obstetric and gynecologic, cardiac, and vascular sonography. Many of these specialty examinations are associated with additional laboratory tests (see Appendix B). For complete descriptions of sonographic competencies and goals, the Sonography Clinical Assessment Notebook (SCAN), developed by the International Foundation for Sonography Education and Research is highly recommended for students, instructors, and working sonographers. It is available at www.ifser.squarespace.com. Regularly updated, the SCAN, and its electronic counterpart, the mSCAN, are valuable compendiums of specialty information. The SCAN and mSCAN contain specialty-specific master proficiency lists and performance objectives, guidelines, clinical evaluation forms, and logbook forms to document satisfactory mastery of specific scanning objectives. A completed SCAN is a record of an individual learner’s clinical competency and professionalism (Figure 6-1).

Patient positioning

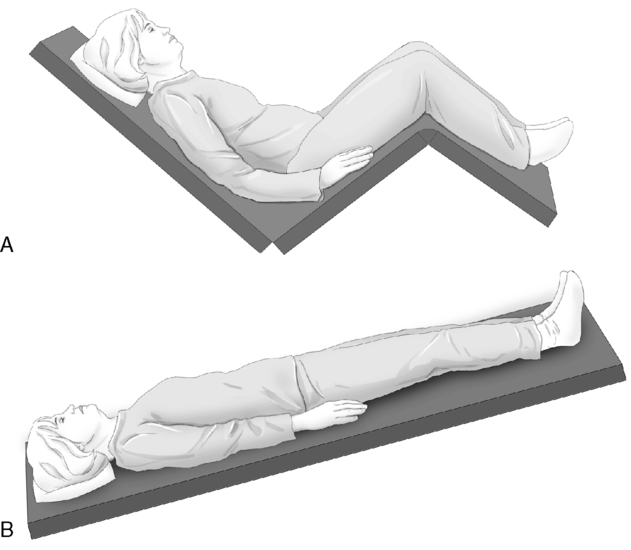

An important part of performing sonography examinations is correct positioning of the patient and knowing when a position change can enhance the visualization of an area of interest. Figure 6-2 depicts the patient positions most commonly used in sonography.

Scanning planes

1. Sagittal: The scan plane is longitudinal (lengthwise) down the patient’s body, dividing the body into right and left sides. The midsagittal plane divides the body into equal right and left sides.

2. Transverse: The scan plane that is horizontal across the patient’s body, or 90 degrees to the sagittal plane.

3. Coronal: The scan plane is a vertical plane at right angles to a sagittal plane. The coronal plane divides the body into anterior (front) and posterior (back) portions.

4. Oblique: Any plane not parallel to the three planes mentioned above.

Routine duties

Later in the chapter, scanning protocols for the four major specialty areas are presented in detail. However, a number of study-related and non–study-related duties apply to all ultrasound examinations. Regardless of the setting (e.g., hospital, clinic) or the type of examination, these routine duties are necessary to ensure quality and diagnostic patient studies and that the ultrasound laboratory functions smoothly and efficiently and can meet laboratory accreditation requirements (Box 6-1).

Patient Preparation

Before commencing any ultrasound study, the sonographer must carry out several important tasks:

• Review the patient’s chart to verify the physician’s order and evaluate whether the ultrasound examination ordered is appropriate, given the patient’s symptoms and clinical diagnosis.

• Check the results of any prior diagnostic tests.

• Mentally review the sonographic protocols most likely to answer the clinical question(s).

• Inform the patient of the purpose of the ultrasound examination.

• Ascertain whether the patient has followed any required pre-examination preparations.

• Conduct a brief, but pertinent, patient history.

• Question the patient about any possible latex allergies.

• Perform a brief physical examination, if indicated by the ultrasound exam.

• Instruct the patient on disrobing.

• Position the patient on the scanning table.

• Select the appropriate instrumentation for the examination based on the patient’s body habitus and the examination objectives.

Technical Reports

In many ultrasound departments, sonographers are required to provide a preliminary report of their findings and observations upon completion of the ultrasound study. To avoid litigation, the preliminary report may be referred to as the technical, or sonographer’s, impression, meaning that, as such, it is subject to reinterpretation. Technical difficulties encountered during the study should be documented and explained. Any report generated by a sonographer should indicate only essential sonographic findings and not attempt to provide a diagnosis (Box 6-2).

Procedural and Diagnostic Coding

In some ultrasound settings an additional sonographer duty is to enter the appropriate current procedural terminology (CPT) coding for each examination (Box 6-3). Initially instituted by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), the task of maintaining and updating the CPT codes has been given to the American Medical Association (AMA). The purpose of the coding system is as follows:

• Provide uniform language that accurately describes medical, surgical, and diagnostic procedures performed by physicians and other health care providers.

• Assist in the assignment of reimbursement amounts to providers by Medicare carriers.

Quality Assurance Testing

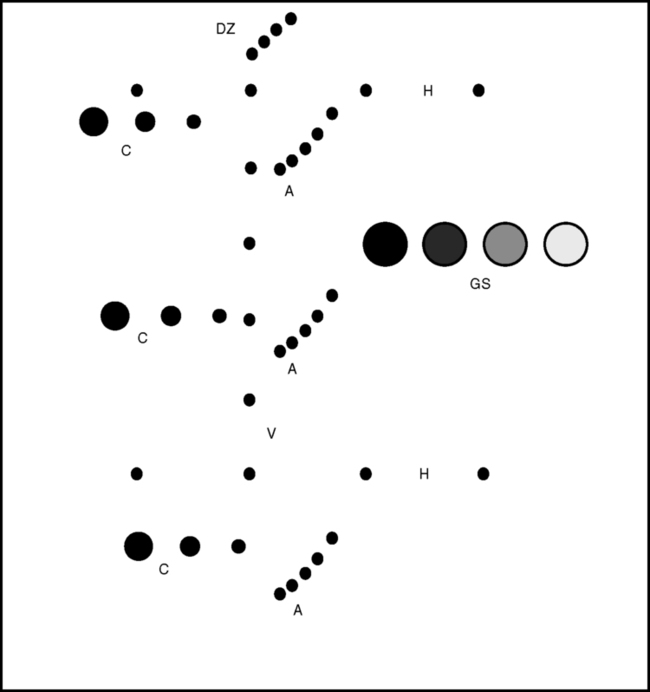

Basic tests of the equipment should be performed on a regular basis and the results recorded in an equipment log or notebook. The areas for testing include instrument sensitivity evaluation, image photography uniformity, and vertical/horizontal measurement accuracy (Figure 6-4).

Transducer Preparation and Care

Strong glutaraldehyde solutions often are used to disinfectant transducers, but growing concern exists over the potential adverse effects of being exposed to glutaraldehyde liquids and vapors. The sonographer should check with his or her institution’s infection control supervisor to be sure that any transducer soaking cups or cleansing stations meet current Occupational Safety and Health Administration and Joint Commission requirements. (These requirements may be found at http://www.osha.org and http://www.jointcommission.org.) Guidelines for cleaning and preparing endocavitary ultrasound transducers are available at the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) website (http://www.aium.org).

Specialty ultrasound protocols

Abdominal and retroperitoneal sonography

Contributed by Robert DeJong, RDMS, RDCS, RVT, FSDMS

Clinical indications include the following:

• Pain in the abdomen, flank, and/or back

• Referred pain from the abdominal or retroperitoneal regions

• Abnormal laboratory or physical findings

• Evaluation of known or suspected abnormalities

• Exploration for primary or metastatic disease

• Evaluation of known or suspected congenital abnormalities

• Evaluation of pre-transplant and post-transplant patients

• Identification of calculi in the urinary tracts

• Assessment and evaluation of tumors, cysts, abscesses, or fluid

• Evaluation of the abdominal arteries for the presence of an aneurysm

• Evaluation of narrowing of the abdominal arteries

• Guidance during aspiration or biopsy procedures

• Location of a foreign object within the abdominal/retroperitoneal organs or cavities

Preliminary Steps for Abdominal and Retroperitoneal Examinations

2. Identify the patient in accordance with the National Safety Patient Goals (NSPGs) published by The Joint Commission.

3. Confirm that the patient’s preparation for the abdominal sonographic examination has been followed.

4. Take the patient’s history and include the following information:

• Location of any pain, (e.g., right or left upper quadrant, general abdominal, or midabdominal)

• Feeling of fullness, fever, nausea, vomiting, burning, belching, or regurgitation related to certain types of food (e.g., fatty foods, fried foods)

• Flank pain or urinary tract symptoms (e.g., hematuria or cloudy urine)

5. Review the patient’s medical history and look for a history of infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, hepatitis), alcohol intake, drug use, personal or family history of carcinoma, known congenital anomalies, previous surgeries, and other disease processes.

6. Obtain a list of present medications, if required, especially before interventional procedures. (This is a National Safety Patient Goal.)

7. Document the findings of normal and abnormal values of laboratory tests, especially aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, amylase, lipase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urinalysis.

8. Review any prior ultrasound or other diagnostic imaging tests, including abdominal radiographs, nuclear medicine, PET scans, CT scans, and MRI. If the images are not available, any reports should be read.

Beginning the Ultrasound Examination

• Mid quadrants: transverse images at the level of the umbilicus

• Lower quadrants: transverse images at the level of the iliac crests

• Aorta and distal aorta, if patient is older than 55 years of age

• Right, left, and caudate lobes of the liver

• Main lobar fissure and gallbladder

• Lateral aspects of the liver and spleen to view diaphragms and pleural spaces

• Adrenal gland area (Note: On pediatric patients the adrenal glands are seen routinely, whereas on adults they are seen infrequently.)

Transverse views should include the following:

• Porta hepatis to demonstrate common duct, portal vein, and hepatic artery

• Liver to demonstrate the right, left, and caudate lobes

• Gallbladder to demonstrate the neck, body, and fundus of the gallbladder

• Pancreatic region to demonstrate the head, uncinate process, body, and the tail

• Right and left kidneys to demonstrate the upper, mid, and lower poles

Left lateral decubitus (right side up) views should include the following:

• Longitudinal views through the gallbladder

• Longitudinal view through the common duct

• Transverse views of the gallbladder at the level of the neck, body, and fundus

• Additional views as needed. Upright scans may be useful in revealing the presence of gallbladder sludge or stones. Prone scans are helpful in visualizing the kidneys, especially when bowel gas obscures the lower poles.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree