The clinical evaluation of patients with tinnitus differs based on whether the tinnitus is subjective or objective. Subjective tinnitus is usually associated with a hearing loss, and therefore, the clinical evaluation is focused on an otologic and audiologic evaluation with adjunct imaging/tests as necessary. Objective tinnitus is divided into perception of an abnormal somatosound or abnormal perception of a normal somatosound. The distinction between these categories is usually possible based on a history, physical examination, and audiogram, leading to directed imaging to identify the underlying abnormality.

Key points

- •

The clinical evaluation of patients with tinnitus differs based on whether the tinnitus is subjective or objective.

- •

Subjective tinnitus is usually associated with a hearing loss, and therefore, the clinical evaluation is focused on an otologic and audiologic evaluation with adjunct imaging/tests as necessary.

- •

Objective tinnitus is divided into perception of an abnormal somatosound or abnormal perception of a normal somatosound.

- •

The distinction between these categories is usually possible based on a history, physical examination, and audiogram, leading to directed imaging to identify the underlying abnormality.

Introduction

Tinnitus is defined as the perception of sound in the absence of an external sound source. It is further categorized as subjective or objective ( Table 1 ). Subjective tinnitus may be primary, which may or may not be associated with sensorineural hearing loss, or secondary to a variety of conditions, such as conductive hearing loss, auditory nerve disease, and other conditions. Subjective tinnitus is a purely electrochemical phenomenon and is never audible to an external listener. The site, or more likely sites, of origin of subjective tinnitus likely varies between patients, and identification of potential sites is a subject of intense research efforts. Objective tinnitus is the perception of an actual, mechanical somatosound. Depending on the nature and location of the source, as well as the diligence of the examiner, it may be audible to an objective listener. The most common objective tinnitus arises from self-perception of a vascular somatosound, a so-called pulsatile, or more properly pulse-synchronous, tinnitus. Objective tinnitus can be caused by the perception of an abnormal somatosound, that is, abnormal sound production, or a heightened auditory sensitivity to a normal somatosound, that is, abnormal sound perception. Examples of the former include an arterial-venous malformation or a sigmoid sinus diverticulum, and examples of the latter include a variety of conditions resulting in conductive hearing loss or a pathologic third mobile window of the otic capsule.

| Type of Tinnitus | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Perception of an abnormal somatosound |

|

| Abnormal perception of a normal somatosound |

| |

| Subjective | Primary |

|

| Secondary |

| |

The clinical evaluation of the patient with tinnitus is focused on gathering the necessary information to determine the type and cause of this disorder and to formulate thereby an appropriate treatment approach. Although the articles in this issue are focused primarily on objective, pulse-synchronous tinnitus, nonrhythmic, subjective tinnitus is far more common, representing more than 90% of all patients with a chief complaint of tinnitus. Subjective tinnitus, although rarely treated by surgical intervention, also warrants a thorough neurotologic evaluation, sometimes supplemented by diagnostic imaging, with a goal of identifying potentially worrisome or treatable causes. Importantly, because of the high prevalence of subjective tinnitus (30% in individuals 55–99 years old ), many patients will report more than one type of tinnitus, each requiring the appropriate clinical evaluation.

Introduction

Tinnitus is defined as the perception of sound in the absence of an external sound source. It is further categorized as subjective or objective ( Table 1 ). Subjective tinnitus may be primary, which may or may not be associated with sensorineural hearing loss, or secondary to a variety of conditions, such as conductive hearing loss, auditory nerve disease, and other conditions. Subjective tinnitus is a purely electrochemical phenomenon and is never audible to an external listener. The site, or more likely sites, of origin of subjective tinnitus likely varies between patients, and identification of potential sites is a subject of intense research efforts. Objective tinnitus is the perception of an actual, mechanical somatosound. Depending on the nature and location of the source, as well as the diligence of the examiner, it may be audible to an objective listener. The most common objective tinnitus arises from self-perception of a vascular somatosound, a so-called pulsatile, or more properly pulse-synchronous, tinnitus. Objective tinnitus can be caused by the perception of an abnormal somatosound, that is, abnormal sound production, or a heightened auditory sensitivity to a normal somatosound, that is, abnormal sound perception. Examples of the former include an arterial-venous malformation or a sigmoid sinus diverticulum, and examples of the latter include a variety of conditions resulting in conductive hearing loss or a pathologic third mobile window of the otic capsule.

| Type of Tinnitus | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Objective | Perception of an abnormal somatosound |

|

| Abnormal perception of a normal somatosound |

| |

| Subjective | Primary |

|

| Secondary |

| |

The clinical evaluation of the patient with tinnitus is focused on gathering the necessary information to determine the type and cause of this disorder and to formulate thereby an appropriate treatment approach. Although the articles in this issue are focused primarily on objective, pulse-synchronous tinnitus, nonrhythmic, subjective tinnitus is far more common, representing more than 90% of all patients with a chief complaint of tinnitus. Subjective tinnitus, although rarely treated by surgical intervention, also warrants a thorough neurotologic evaluation, sometimes supplemented by diagnostic imaging, with a goal of identifying potentially worrisome or treatable causes. Importantly, because of the high prevalence of subjective tinnitus (30% in individuals 55–99 years old ), many patients will report more than one type of tinnitus, each requiring the appropriate clinical evaluation.

Clinical evaluation of tinnitus

Basic Otologic Evaluation

History

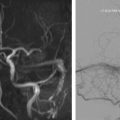

The clinical evaluation of tinnitus begins with a complete history and a head and neck examination. A conceptual challenge in the evaluation of tinnitus consists of the categorization of tinnitus into objective and subjective. Historically, objective tinnitus was considered one that a clinician can also hear as part of the medical evaluation. However, as noted earlier, this is not always the case, and true mechanical somatosounds may not be audible even to the most diligent listener. A more useful clinical definition of objective tinnitus is that which, based on its clinical characteristics, is thought to arise from perception of an actual, mechanical somatosound. Therefore, the first step in the evaluation of tinnitus is a clear characterization of the chief complaint and specifically the acoustic nature of the tinnitus ( Fig. 1 ). Based on the patient’s description, it is almost always possible to determine if the tinnitus is a result of a somatosound. The most common somatosounds are typically described as “a heartbeat in the ear,” “a pulsating hum,” “a whooshing sound,” “clicking,” or “fluttering,” depending on their source. Vascular somatosounds often increase in loudness and rate with physical activity and may be modulated by compression or rotation of the neck or other head movements. In contrast, subjective tinnitus is usually described as a continuous high-pitched beep, ringing, cricketlike sound, roaring, ocean noise, or humming. Subjective tinnitus is less likely to be affected by changes in head position or pressure on the neck, although a subgroup of subjective tinnitus sufferers—those with a so-called somatic tinnitus—may be able to alter the quality of the sound, or even abolish it, with certain actions, commonly jaw clenching or thrusting, or occipital pressure. Both types of tinnitus tend to be more bothersome in a quiet acoustic environment, although some patients with subjective tinnitus have worsening symptoms in the presence of sound.

In addition to categorizing the tinnitus as subjective or objective based on the acoustic characteristics and pattern, additional questioning should determine laterality; duration of symptoms; persistence (constant vs intermittent); exacerbating and alleviating factors, including whether the tinnitus is worse in a noisy or quiet environment, with or following certain activities, dietary factors, or seasonal or daily fluctuations. It is critically important to distinguish whether the tinnitus is bothersome or intrusive, because this factor will influence the treatment options to be offered. Patients should be asked about associated symptoms, such as subjective hearing loss, disequilibrium or vertigo, autophony (hearing their own voice in their ear), otalgia, otorrhea, aural fullness or pressure, and blurry vision. The otologic history should include questions about childhood ear infections, noise exposure, known otologic disease, or trauma. The general past medical history should include questions directed at detecting a history of high blood pressure, vascular malformations, carotid stenosis and atherosclerotic disease, stroke or transient ischemic attacks, rapid weight gain or loss, migraine and other types of headache, visual changes, anemia, and thyroid function. Other pertinent information includes a previous history of cancer or chemotherapy (which may also be associated with weight loss), medications, and family history of hearing loss, ear disease, or vestibular schwannoma.

Physical examination

The physical examination consists of a complete head and neck examination, supplemented by a neurotologic examination that includes evaluation of eye movements for nystagmus, complete assessment of cranial nerve function, and a careful otoscopic examination. Auscultation in multiple locations over the mastoid process and over the carotid arteries is critical in patients complaining of perception of a pulse-synchronous sound. If the examiner can perceive the sound themselves, this increases the likelihood that a cause will be identified, and it also provides the patient with much needed reassurance that there is an objectively identifiable correlate for their subjective perception. The authors prefer to use a digital stethoscope (Thinklabs One; Thinklabs Medical LLC, Quebec, Centennial, CO, USA www.thinklabs.com ) with noise-cancellation headphones for the greatest sensitivity, although conventional electronic stethoscopes or traditional acoustic stethoscopes are also useful. In addition, a Toynbee tube can be used for auscultation within the external auditory canal.

Once tinnitus is classified as objective or subjective based on the history and physical examination, it is important to assess the patient’s hearing. Specifically, it is critical to determine whether there is an associated hearing loss, and if so, whether it is conductive or sensorineural. Hearing is the auditory sensation of environmental movement. Sound is compression and rarefaction of air. Sound waves are transmitted through the external auditory canal to the lateral surface of the tympanic membrane. The tympanic membrane is the lateral border of the middle ear. The sensory cells of hearing, the hair cells, are located in the cochlea, which is a fluid-filled structure in the inner ear. The middle ear is an air-filled chamber that serves as an impedance matching system between the air of the external auditory canal and the fluid of the inner ear. The ability of sound to overcome the impedance mismatch between air and fluid and propagate to the hair cells depends in part on the large vibratory surface area of the tympanic membrane in comparison to the small surface area of the stapes footplate as well as the elasticity of the tympanic membrane and the lever arms of the ossicular chain. Impedance matching also requires equalization of pressure between the middle ear and external auditory canal. Middle ear pressure equilibrates via the eustachian tube, a bony and cartilaginous canal that opens in the nasopharynx, where it is exposed to ambient air pressure.

Processes that disrupt the sound conduction mechanism can lead to conductive hearing loss. These processes can be disorders that prevent sound from reaching the tympanic membrane such as cerumen impaction or otitis externa, violate tympanic membrane integrity such as a perforation, disrupt the ossicular chain such as otosclerosis, cholesteatoma, or necrosis, and/or alter middle ear aeration such as the various forms of eustachian tube dysfunction. Individuals with a conductive hearing loss tend to have a heightened sensation of somatosounds, such that sounds normally produced in the body but typically masked by ambient noise are now audible; this is commonly observed in nonpathologic settings when an individual perceives their heartbeat in the ear resting on a pillow while trying to fall asleep. A second process that can result in a heightened sensation of somatosounds is an otic capsule third mobile window syndrome, most commonly seen with superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD) syndrome. Although third mobile windows can produce a sensorineural hearing loss, they can also result in better than normal bone conduction with a conductive hyperacusis, usually in the lower frequencies.

Careful examination for evidence of abnormality that can result in a conductive hearing loss is a critical part of the evaluation of the patient with tinnitus. In addition to otoscopy, this includes tuning fork tests. The Weber and Rinne tests can suggest a sensorineural or conductive hearing loss. Auditory perception of a tuning fork placed on the lateral malleolus, the so-called lateral malleolar sign, can suggest a third mobile window syndrome or other conductive hyperacusis. Before performing the otologic examination, cerumen should be meticulously removed to allow proper visualization of the entire tympanic membrane. Although sensorineural hearing loss is commonly associated with subjective tinnitus, conductive hearing loss can also result in an identical perception. Therefore, evaluation of a patient with tinnitus is not complete without comprehensive audiometry.

Audiogram

Every patient evaluated for tinnitus should have a comprehensive audiogram. This examination consists of several components: (1) Measurement of pure tone thresholds: Assessment of the threshold at which the patient is able to detect pure tones varying in frequency from 250 to 8000 Hz. This assessment is a behavioral test of a psychophysical measure, because it depends on the patient’s report of the minimal intensity at which a sound was audible. Sounds are presented via air (eg, headphones) and bone conduction (using a bone transducer). If the detection of sound is better when the sound is introduced via bone than via air, a so-called air-bone gap conductive abnormality is implied and quantified. Normal hearing is accepted as a threshold of less than 15 dB at all frequencies tested for both ears. Most of the population starts to lose sensitivity to higher frequencies at puberty, and this progresses with age. Any hearing loss can be associated with subjective tinnitus. (2) Speech audiometry: This determines both the minimal intensity at which spoken words (spondees) can be repeated 50% of the time (speech reception threshold), and the percentage of words that the patient repeats correctly when presented at a suprathreshold stimulus (word recognition score). Beyond the functional significance of the tests, the results can suggest a retrocochlear abnormality, such as a vestibular schwanomma (a cause of subjective hearing loss), when the word recognition is decreased out of proportion to an increase the pure tone thresholds. (3) Acoustic reflex testing: This measures reflex contraction of the stapedius muscle in response to an ipsilateral or contralateral acoustic stimulus. The reflex arc passes through the eighth nerve, auditory and facial nuclei, and facial nerve. This acoustic reflex testing is an objective and quantitative test and can therefore sometimes be helpful in detecting malingerers with inconsistent responses on behavioral tests. Acoustic reflexes are often lost with retrocochlear abnormality, due to abnormality in the afferent limb, and at a very low threshold with most middle ear conductive abnormality, due to an absence of or inability to record the response. However, in a patient with air-bone gaps on pure tone testing, and intact acoustic reflexes, a third mobile window syndrome should be suspected. (4) Impedance testing: This test is another mechanical measure of middle ear function and assesses movement of the tympanic membrane and the pressure in the middle ear cleft, providing objective and quantitative information on the function of the eustachian tube. Acoustic reflex and impedance testing are together referred to as measures of immittance.

At the completion of the history, physical examination, and audiogram, the clinician should be able to determine if the tinnitus is likely objective or subjective and proceed with further evaluation, as needed, using a disease-specific approach ( Table 2 ).