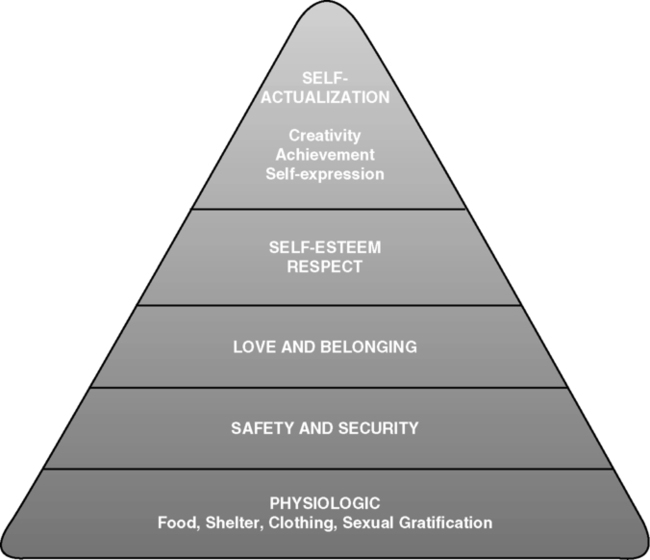

Students who successfully complete this chapter will be able to do the following: • Define communication and the components necessary for communication to occur. • Compare and contrast verbal and nonverbal communication. • Identify communication barriers. • Explain how culture and religion can influence health and illness. • Discuss various approaches used in communicating with patients who require special assistance. • List the advantages and disadvantages of sonographer reports, including the creation of images (films and tapes) for patient use. Maslow arranged these needs from the lowest to highest levels and postulated that lower-level needs must be met before higher-level needs could be achieved. Picturing these needs in the shape of a pyramid, with physical needs forming the base of the pyramid, is helpful (Figure 3-1). Nonverbal communication accounts for a large percent of our daily communications. Nonverbal communication consists of eye contact, facial expressions, body language, gestures, posture, tone of voice, and touch. In some instances the message a patient wishes to impart is contradicted by the accompanying nonverbal expressions. To be effective communicators, sonographers must develop communication skills and the ability to listen and convey interest,compassion, knowledge, and information. Getting feedback is the second most important factor in communication because it assures you that your message was properly conveyed to the receiver (Box 3-1). Supportive communication is more goal oriented and bears more information than social conversation. Important patient information is discussed—how patients feel—and any problems that concern them can be shared. The purpose of supportive communication is to help relieve patient anxiety, anger, or frustration and to learn about any unmet patient needs. By talking through such concerns, the sonographer often can help patients resolve their problems. However, only if sonographers really understand the patient can supportive communication be successful. This can be accomplished by means of the skills listed in Box 3-2. Whenever a listener prevents a conversation from starting or continuing, the communication is cut off. Common reasons why listeners do this are embarrassment, feeling threatened, or distrust of the sender. Such tactics may be conscious or subconscious. Box 3-3 lists responses that stop or cut off communication. Sonographers always should show respect for patients by a willingness to listen—without judgment—to their concerns and feelings. Give accurate information. If you do not know the facts, or if you are not free to discuss them, find someone who is authorized to give that information. Patients must be able to trust your honesty.

Communication and Critical Thinking Skills

Basic survival needs

Communication

Types of communication

Communication factors

Barriers

Cutting Off Communication

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine