LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Recognize venolobar syndrome on a frontal chest radiograph, chest-computed tomography (CT), and chest magnetic resonance image and explain the etiology of the retrosternal band of opacity seen on the lateral radiograph.

2. Name the components of pulmonary venolobar syndrome.

3. Recognize a mass in the posterior segment of a lower lobe on a chest radiograph and CT and suggest the possible diagnosis of pulmonary sequestration.

4. Describe the differences between intralobar and extralobar sequestration.

5. Recognize bronchial atresia on a chest radiograph and CT and name the most common lobes in which it occurs.

6. Recognize a cystic mass in the mediastinum and suggest the possible diagnosis of a bronchogenic cyst.

The most common major anomalies of pulmonary development (Table 16.1) span a continuum of maldevelopment involving the pulmonary parenchyma, the pulmonary vessels, or a combination of both (1). At one end of the spectrum, congenital lobar emphysema represents abnormal lung supplied by normal vessels, and at the other end, pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (AVM) consists of abnormal vessels within normal lung parenchyma. Some patients with congenital lung anomalies have mixed features, making exact categorization of the anomaly difficult.

CONGENITAL LOBAR EMPHYSEMA

Congenital lobar emphysema (CLE) is a disorder affecting neonates and young infants, and is usually associated with acute or subacute respiratory distress. It may occasionally present as an incidental finding in adults. Various bronchial and alveolar abnormalities can cause this disorder, and in some cases, the cause is unknown. The most commonly detected abnormality is absence or hypoplasia of cartilage rings of major and branch bronchi, with resultant bronchial collapse during exhalation. This results in inhalational air entry but collapse of the narrow bronchial lumen during exhalation. The bronchial obstruction leads to progressive hyperinflation and air trapping (Fig. 16.1), usually involving only one pulmonary lobe. The left upper lobe is most commonly involved, followed by the right middle and right upper lobes. CLE has two forms: hypoalveolar (fewer than expected number of alveoli) and polyalveolar (greater than expected number of alveoli). The pulmonary vasculature, although frequently attenuated, is usually normal in structure and distribution. Common chest radiographic findings include a hyperlucent lobe, compressive atelectasis of adjacent parenchyma, and contralateral mediastinal shift (1). In some cases, a subtle hyperlucent lobe may be all that is seen. CT best characterizes this abnormality and typically shows a hyperlucent, hyperexpanded lobe; attenuated but intact pattern of vascularity; compression of the adjacent lung; and contralateral mediastinal shift.

Table 16.1 MAJOR ANOMALIES OF PULMONARY DEVELOPMENT

Congenital lobar emphysema

Bronchogenic cyst

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation

Bronchopulmonary sequestration

Pulmonary venolobar syndrome (also called hypogenetic lung syndrome or scimitar syndrome)

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation

Bronchial atresia

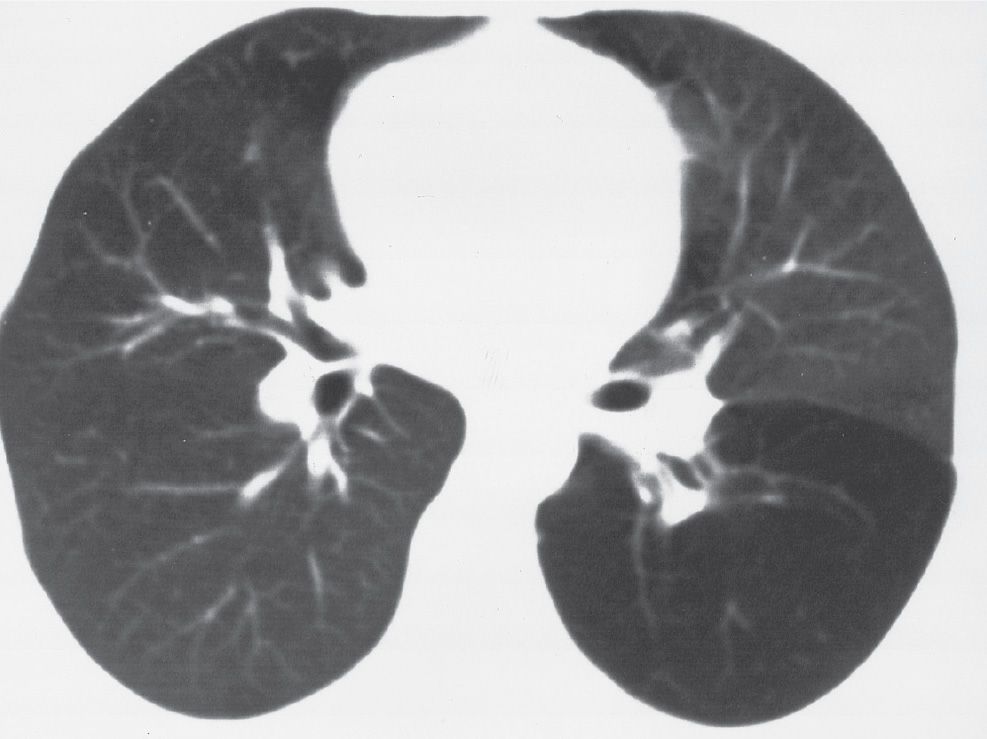

FIG. 16.1 • Congenital lobar emphysema. CT of a 30-year-old asymptomatic woman shows abnormal lucency and diminutive vasculature in the superior segment of the left lower lobe. There was no evidence of an endobronchial lesion on CT or bronchoscopy, and the appearance of the left lower lobe was unchanged for 3 years on follow-up CT scans.

BRONCHOGENIC CYST

Bronchogenic cysts result from abnormal growth of the lung bud and can be either mediastinal or intrapulmonary. Both types are lined with ciliated columnar epithelium and contain serous or mucous material. No clear-cut predilection for an intrapulmonary or a mediastinal location has been demonstrated. An intrapulmonary bronchogenic cyst often communicates with the bronchial tree, which can result in air–fluid levels and recurrent infections that may damage the cyst wall. Chest radiographs show a nonspecific oval or round, well-circumscribed mass, often as an incidental finding. The most common mediastinal location is subcarinal. CT scans show the mass to have a thin or nearly imperceptible wall and to contain fluid, often of water attenuation (see Figs. 6.37 and 6.38). Occasionally, the fluid has a higher attenuation than water because of the presence of proteinaceous material or calcium (see also Chapter 6). The contents of the cyst do not enhance after administration of intravenous contrast material.

CONGENITAL CYSTIC ADENOMATOID MALFORMATION

Congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM), also called congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM), is a hamartomatous abnormality of the lung consisting of a multicystic mass of pulmonary tissue in which there is proliferation of bronchial structures at the expense of alveolar development. Three types have been described. Type 1, the most common type, consists of single or multiple large cysts (up to 10 cm in diameter) and has the best prognosis. Type 2 consists of multiple small cysts (1 to 2 cm in diameter), and type 3 (solid form) is a large, noncystic lesion. The prognosis worsens from type 1 to type 3, in part because of associated anomalies that occur with greater frequency with types 2 and 3.

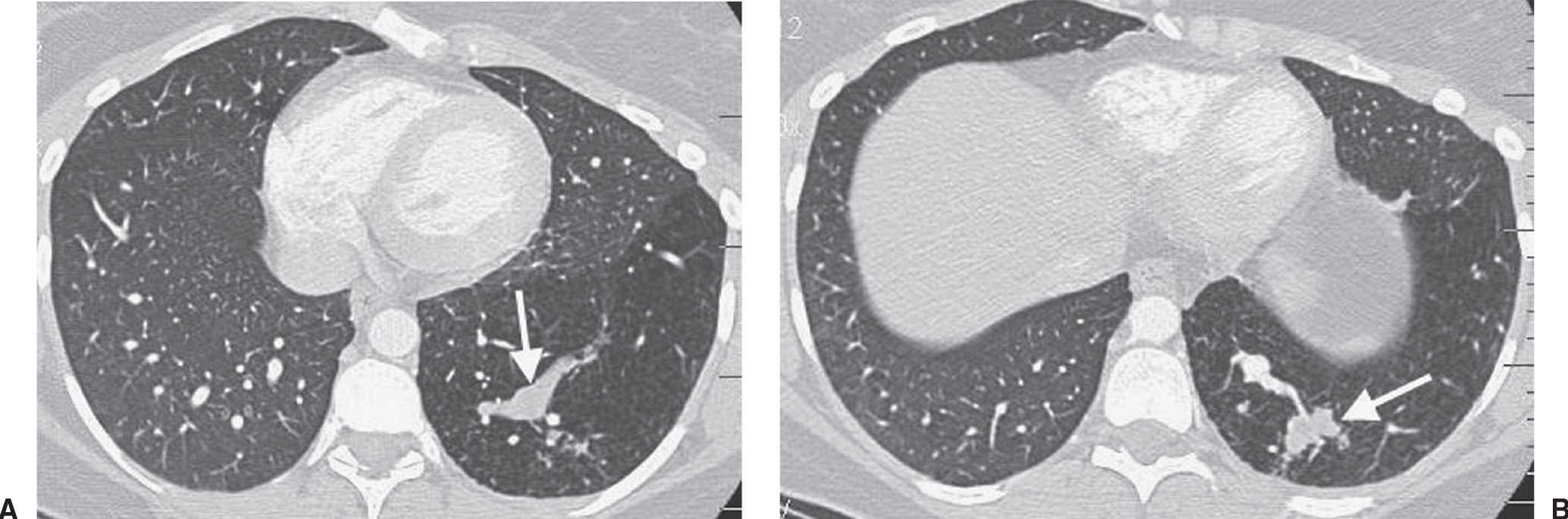

FIG. 16.2 • Intralobar sequestration. A: CT of a 37-year-old woman with chest pain shows a prominent tubular structure in the left lower lobe (arrow). The surrounding lung, also part of the sequestration, is hyperlucent. B: CT at level inferior to (A) shows the tubular structure leading to a lobulated mass (arrow) in the left lower lobe. C: CT with mediastinal windowing shows the tubular structure be an enhancing vessel (arrow). D: CT of the upper abdomen shows a prominent vessel (arrow) arising from the abdominal aorta and heading toward the left lower lobe. E: Coronal reformatted CT confirms that a vessel arises from the abdominal aorta (arrow) and heads superiorly toward the left lower lobe. F: Paddlewheel reformatted CT shows drainage from the left lower lobe mass to the left inferior pulmonary vein (arrow).

The radiographic appearance varies, depending on the type of lesion. The most common presentation is that of a mass of numerous air-containing cysts that expand the ipsilateral hemithorax and shift the mediastinum to the contralateral side. Occasionally, one cyst preferentially expands, creating a single large lucent area that is similar in appearance to CLE. Type 3 lesions present as large homogeneous masses, without cystic spaces. Although most cases of CCAM present in the first month of life, the diagnosis is occasionally delayed until adulthood (2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree