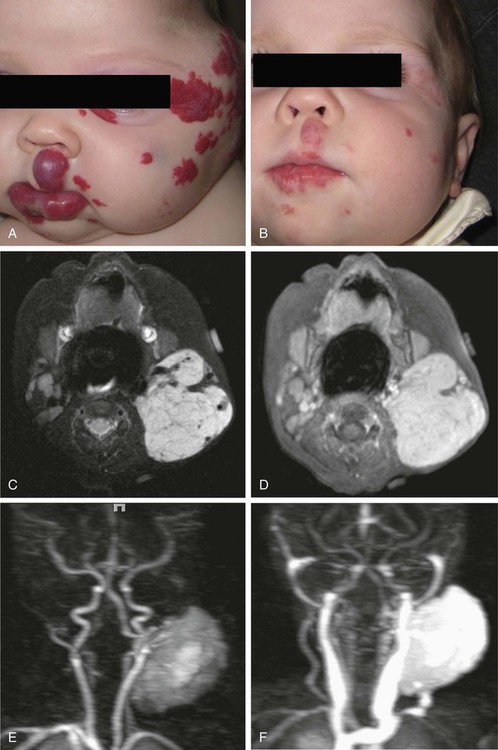

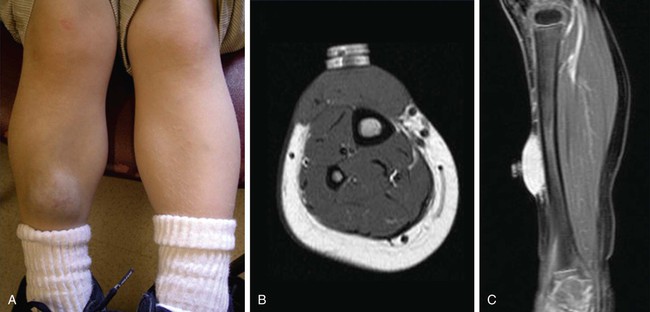

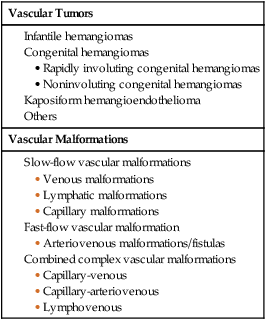

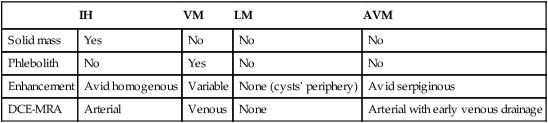

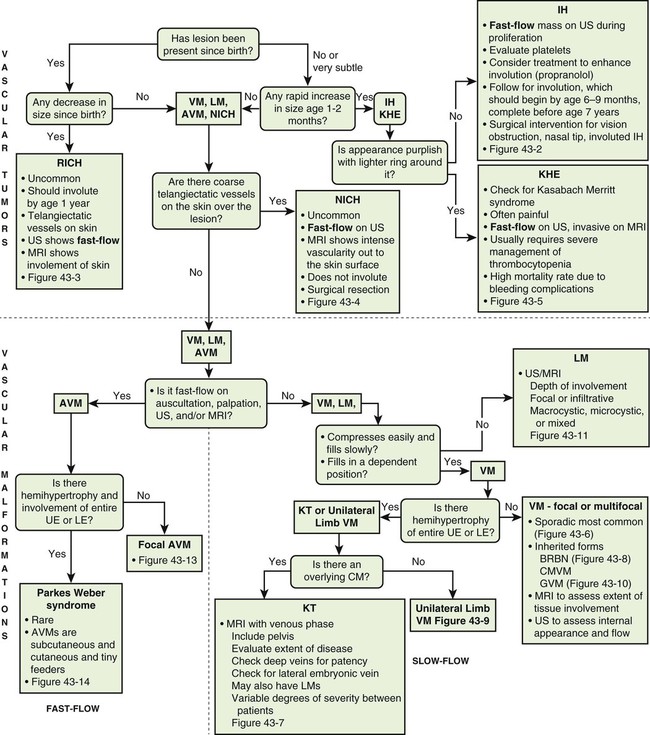

To clarify this situation, the correct terminology for each entity should be consistently used. Even as recently as 2009, Hassanein and Mulliken found that the term hemangioma was used incorrectly in 71.3% of publications that year.1 This emphasizes the importance of understanding the current classification system that was approved by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) in 1996 (Table 43-1), which stems from the biological behavior–based classification system introduced by Drs. Mulliken and Glowacki in 1982.2 TABLE 43-1 Simplified and adapted from the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification, 1996. In this chapter, we will review the ISSVA classification system, which will include both common vascular anomalies and the more complex syndromes. We will describe the clinical presentation and imaging findings of each group/subgroup of vascular anomalies, using a practical approach to correlate clinical presentation with imaging findings (Fig. 43-1 and Table 43-2). TABLE 43-2 Key Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features of Vascular Anomalies Vascular anomalies are divided into two main groups: vascular tumors and vascular malformations.3 The morbidity and treatment for vascular tumors differ dramatically from vascular malformations, and also differ dramatically for each type of vascular tumor and each type of vascular malformation, which is the overriding impetus for clear, standardized classification in the first place. IHs comprise approximately 90% of all vascular tumors. They are the most common vascular tumors of infancy, with a higher incidence in white infants. The highest incidence is noted in preterm infants weighing less than 1000 g.4 Head and neck regions are involved most frequently (60% of cases), followed by the trunk (25% of cases), and extremities (15% of cases).5 IHs are often not apparent at birth but most appear within the first 6 weeks of life as a soft, noncompressible mass with a typical triphasic evolution: proliferation, plateau, and involution. Superficial hemangiomas are generally cherry red macules and papules; deep hemangiomas are firm, rubbery subcutaneous masses, sometimes with a bluish skin hue. Compound hemangiomas combine aspects of both types. Most IHs double in size in the first 2 months of life, and approximately 80% reach their maximum size by 6 months of age.6 Spontaneous regression in early childhood (≈7 years of age) is typical,7,8 but up to 40% of IHs may have residual skin changes and fibrofatty residuum, especially if they involve the head and neck. Patients with large IHs in the head and neck region—where there may be a concern for airway compromise, ulceration, or bleeding—can be medically treated, and propranolol is the leading drug of choice (Fig. 43-2; also see Fig 43-1). The immunohistochemical marker glucose transporter protein isoform 1 (GLUT1) has become a major tool in diagnosing infantile hemangioma, with endothelial cells staining strongly.21 The overwhelming majority of other vascular lesions, including congenital hemangiomas and vascular tumors, do not stain positive for GLUT1.9,10 Imaging is not required for the majority of IHs but can be useful to confirm the suspected diagnosis in atypical lesions, to determine the extent of deep lesions, and to exclude other vascular tumors (such as KHE) or soft-tissue malignancies. US demonstrates a solid mass with increased color flow within the mass.11 The arterial inflow and venous drainage can be visualized by Doppler US.12 MRI reveals a T2 bright, T1 isointense mass with homogenous avid contrast enhancement.13 Internal serpiginous flow voids within the IH noted in T2-weighted imaging represents the arterial inflow, an important diagnostic clue. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRA (DCE-MRA) demonstrates early arterial enhancement in a soft-tissue mass with a draining vein. Typically, no perilesional edema is observed, which facilitates differentiation from other soft-tissue malignancies. Fibrofatty infiltration can be observed during the involuting phase. Clinically, RICH (Fig. 43-3) and NICH (Fig. 43-4; also see Fig. 43-1) appear similar, often presenting as violaceous gray tumors with prominent overlying veins or telangiectases that extend beyond the periphery of the lesion. Many have a lighter or bluish halo on the surrounding skin. In practice, RICH and NICH are distinguished in retrospect, since the former involutes by 12 months of age, and the latter involutes either partially or not at all and requires surgical excision. In addition, RICH can leave significant textural change necessitating reconstructive surgery after involution.14 Early and accurate diagnosis is critical to avoid unnecessary biopsy/surgical intervention.15 Similar histologic and clinical features of RICH and NICH raise the possibility that the latter may undergo involutional arrest to become a noninvoluting tumor.16 KHE is a rare, distinct vascular tumor.17 It may present at birth or within the first few months of life as an ill-defined purpuric mass, often painful, with an encircling pale ring; however, presentation may be later in childhood.18 The destructive/infiltrative nature and very rapid growth of this vascular tumor facilitates differentiation from IH. Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon (KMP, a rare life-threatening condition in which a vascular tumor traps and destroys platelets) can be seen up to 50% of patients. KHE has a high mortality rate (24%) related to coagulopathy or complications from local tumor infiltration. The firm, indurated lesion of KHE has a more invasive appearance and a purplish coloration (Fig. 43-5; also see Fig. 43-1). These cells form slitlike lumina containing erythrocytes that resemble Kaposi sarcoma, thus the name kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

Congenital Vascular Anomalies

Classification and Terminology

Biological Classification of Congenital Soft-Tissue Vascular Anomalies

Vascular Tumors

Vascular Malformations

IH

VM

LM

AVM

Solid mass

Yes

No

No

No

Phlebolith

No

Yes

No

No

Enhancement

Avid homogenous

Variable

None (cysts’ periphery)

Avid serpiginous

DCE-MRA

Arterial

Venous

None

Arterial with early venous drainage

Vascular Tumors

Infantile Hemangiomas

Congenital Hemangiomas

Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Congenital Vascular Anomalies: Classification and Terminology