Deep Venous Thrombosis

Christopher L. Smith

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is defined as a localized area of thrombus within the deep venous system of the lower or upper extremities. The most severe and life-threatening complication of DVT is pulmonary embolism (PE). Ninety percent of pulmonary emboli originate in the deep venous system of the lower extremities and pelvis. Accurate diagnosis and treatment of DVT are necessary to prevent the high morbidity and mortality associated with PE.

Etiology

Risk factors for the development of DVT include history of previous thromboembolic disease, prolonged immobility, obesity, and recent surgery involving the lower extremities and pelvis. Additional risk factors include varicose veins, fracture, trauma, malignancy, autoimmune disorders (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), heart failure, diabetes mellitus, polycythemia vera, hypercoagulable disorders (e.g., antiphospholipid antibody syndrome), pregnancy, oral contraceptives, estrogen replacement, and smoking. These risk factors are all related to the three pathogenic factors for thromboembolism described by Virchow’s triad: venous endothelial damage, hypercoagulability of blood, and decreased blood flow or stasis.

The most common locations for development of DVT include the dorsal veins of the calf, iliofemoral veins, internal iliac veins, and occasionally in the ovarian veins (gonadal veins). DVT has been found to occur more commonly in the left leg than in the right, which is possibly due to the left common iliac vein being slightly compressed by the right common iliac artery as they cross just distal to the bifurcation. Before 1970, DVT of the upper extremity was much rarer (<2). However, the incidence of upper extremity DVT has been increasing since that time because of the increased use of long-term indwelling venous catheters and dialysis shunts.

Symptoms and Signs.

The clinical appearance of DVT is neither sensitive nor specific. It is estimated that 50% of DVT are clinically silent. When present, clinical findings include leg swelling (especially if asymmetric or unilateral), warmth, erythema, pain, tenderness, a positive Homans’ sign, fever, and leukocytosis.

Differential Diagnosis.

Entities that can mimic the clinical appearance of DVT include cellulitis, Baker’s cyst (especially if acutely dissecting), superficial thrombophlebitis, arterial insufficiency, “compartment syndromes,” and myositis.

Indications.

When available, ultrasonography is the initial study of choice for the detection of DVT in the thigh and popliteal veins. This modality is also useful for evaluation of thrombus within the upper extremities. It is a noninvasive test with no

radiation exposure and has been found to be accurate with a high sensitivity (97%) and specificity (95%) for thrombus above the knee. It is less sensitive for the small veins in the calf for which treatment with anticoagulation is controversial and is usually not performed.

radiation exposure and has been found to be accurate with a high sensitivity (97%) and specificity (95%) for thrombus above the knee. It is less sensitive for the small veins in the calf for which treatment with anticoagulation is controversial and is usually not performed.

Protocol.

Lower extremity—a high frequency linear array transducer should be used (5 MHz). The patient is positioned supine with the leg slightly externally rotated and the knee slightly flexed. The femoral vein is located in the groin (medial to the femoral artery) and is then followed down the thigh to the popliteal vein, with the examination including the common femoral vein, superficial femoral vein, popliteal vein, profunda femoral vein, and greater saphenous vein. Additionally, both external iliac veins are imaged (even if the study is a unilateral lower extremity evaluation). If thrombosis is detected in the femoral veins, the common iliac veins and inferior vena cava (IVC) should be imaged in order to determine the extent of thrombus. The veins are examined in both longitudinal and transverse planes with graded compression and Doppler images. Furthermore, a spectral waveform is also obtained, typically in conjunction with augmentation. This is performed by manually squeezing the patient’s calf while imaging with the pulsed Doppler cursor in the vein. Augmentation should not be performed if thrombus is visualized, as this maneuver can cause a thrombus to embolize.

A similar technique is used when evaluating the upper extremity veins for DVT. The venous structures typically evaluated include the internal jugular, brachiocephalic (to the extent that it can be visualized), subclavian, axillary, brachial, cephalic, and basilic veins.

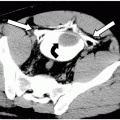

Possible Findings (Fig. 49-1)

Intraluminal thrombus. The thrombus may be occlusive (complete absence of flow) or nonocclusive (partial or mural thrombus).

Lack of compressibility. A normal vein is highly compliant and will collapse with direct external compression by the ultrasound transducer. If a thrombus is present, the vein will not compress completely.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree