than African Americans. Obesity is associated with a higher incidence of osteoarthritis in the knees, which may be related to an excessive weight-bearing load on these joints.

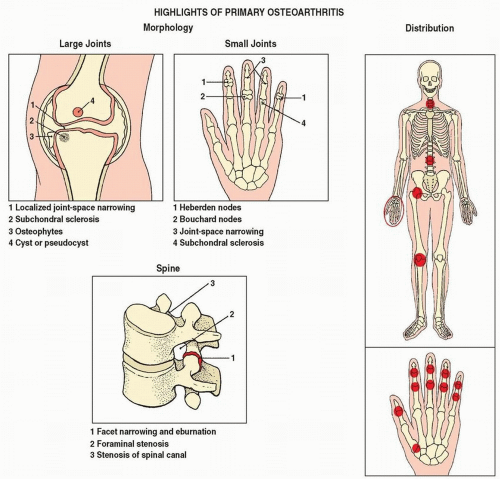

Figure 5.1 ▪ Highlights of the morphology and distribution of arthritic lesions in primary osteoarthritis. |

Table 5.1 CLINICAL AND IMAGING HALLMARKS OF DEGENERATIVE JOINT DISEASE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 5.2 ▪ Pathology of osteoarthritis of hip joint. Coronal section of the resected femoral head (A) and radiograph of the gross specimen (B) show a large flat osteophyte extending from the medial aspect to the region of fovea (arrows). (Modified from Bullough PG. Atlas of Orthopedic Pathology with Clinical and Radiologic Correlation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992, Figs. 10.11 and 10.12, p. 10.5.) |

Figure 5.3 ▪ Pathology of osteoarthritis of hip joint. Coronal section of the osteoarthritic femoral head shows subchondral bone partially denuded of articular cartilage (arrow). Some articular cartilage remains intact (arrowhead). Observe in the exposed subchondral bone focal bone marrow necrosis (yellow area) because of localized overloading (curved arrow). (Modified from Bullough PG. Atlas of Orthopedic Pathology with Clinical and Radiologic Correlation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992, Fig. 9.31.) |

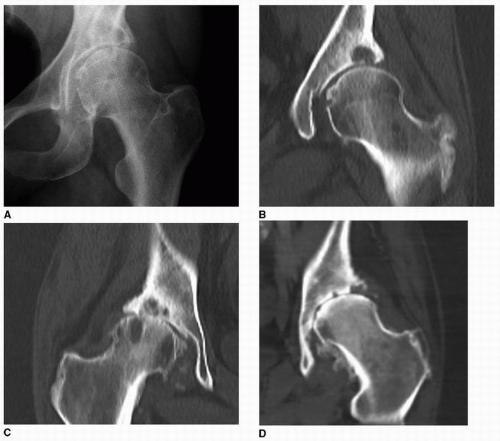

Narrowing of the joint space as a result of thinning of the articular cartilage.

Subchondral sclerosis (eburnation) caused by reparative processes (remodeling).

Osteophyte formation (osteophytosis) as a result of reparative processes in sites not subjected to stress (so-called low-stress areas), which are usually marginal (peripheral) in distribution.

Cyst or pseudocyst formation resulting from bone contusions that lead to microfractures and intrusion of synovial fluid into the altered spongy bone; in the acetabulum, these subchondral cystlike lesions are referred to as Eggers cysts.

Figure 5.4 ▪ Histopathology of osteoarthritis of hip joint. Photomicrograph of a portion of the articular cartilage of a femoral head shows a fibrous pannus extending over the articular surface (H&E, original magnification ×4). (From Bullough PG. Atlas of Orthopedic Pathology with Clinical and Radiologic Correlation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Gower Medical Publishing; 1992, Fig. 9.43, p. 9.17.) |

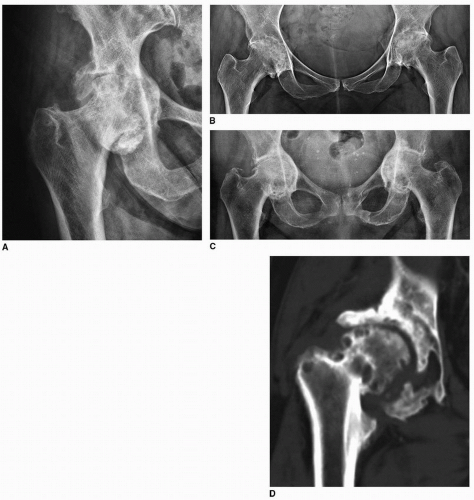

slowly progressive osteoarthritis of the hip is converted into the rapidly progressive, aggressively destructive disease that completely destroys the hip joint. In some of the patients, the major portion of the femoral head may completely disappear. The acetabulum became concentrically enlarged. The pain in the hip is typically disabling and unrelenting. This destructive arthrosis of the hip joint is known as Postel coxarthropathy, a condition characterized by rapid chondrolysis that may quickly lead to complete destruction of the hip joint. Originally described by Lequesne, and also by Postel and Kerboull in 1970, this unique hip disorder occurs predominantly in women, with age of onset at 60 to 70 years. In all cases, a rapid clinical course of hip pain is the consistent common symptom. The histologic findings are those of conventional osteoarthritis with severe degenerative changes in the articular cartilage. However, osteophyte formation is absent or minimal. Hypervascularity in the subchondral bone is a common finding. The bone trabeculae are either abnormally thickened or abnormally thinned. Occasionally, one can observe foci of fibrosis, interstitial edema and hemorrhage in the marrow spaces, focal marrow fat fibrosis, and focal areas of bone resorption. The precise pathogenesis of this condition remains unclear, although direct drug toxicity and the analgesic effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been implicated. Some investigators have suggested that intra-articular deposition of hydroxyapatite crystals might lead to joint destruction. Others have proposed subchondral bone ischemia, cell necrosis, and insufficiency fracture of the femoral head as a cause of this arthritis. Some investigators demonstrated elevated levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) in the joint fluid as well as elevated secretion of matrix metal-loproteinases by fibroblasts from the synovium and subchondral cysts. Because of the rapidity of the process, the radiographic presentation of this condition is marked by very little, if any, reparative changes, mimicking infectious or neuropathic arthritis (Charcot joint) (Figs. 5.12, 5.13, 5.14). More recently, Boutry and colleagues reported magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of this form of osteoarthritis. These included joint effusion, a bone marrow edema-like pattern in the femoral head, neck, and acetabulum; femoral head flattening; and cystlike subchondral defects (Fig. 5.15).

joint, particularly flexion and internal rotation; and (c) imaging findings on conventional radiography, CT, and MRI. In cam type, conventional radiography demonstrates excessive bone formation at the femoral head/neck junction with loss of normal anatomic “waist” at this site (Fig. 5.25A), occasionally resembling the smooth hand grip of some pistols (“pistol grip deformity” or a “cam effect”) (Fig. 5.25B); an os acetabulum, which more likely represents an osseous metaplasia of the cartilaginous labrum or a fragment of damaged acetabular rim; and a radiolucent lesion at the head/neck junction, formerly called synovial herniation pit, and now designated as fibroosseous lesion. CT shows these abnormalities even better (Fig. 5.26). MR arthrography (MRa), particularly the radial reformatted images, in addition to the findings listed previously, clearly demonstrates abnormalities of the fibrocartilaginous labrum at the anterosuperior portion of the acetabulum (Fig. 5.27; see also Fig. 2.91). In pincer type, particularly in case of acetabular retroversion, conventional radiograph shows “crossover” sign, when more lateral projection of anterior acetabulum, which normally should project medially to the posterior acetabulum, “crosses” the

posterior acetabular outline (Fig. 5.28). MRI demonstrates acetabular version and depth of the femoral head coverage (Fig. 5.29). To determine the sphericity of the femoral head and the prominence of the anterior femoral head/neck junction, the alpha angle is calculated on the oblique axial CT or oblique axial MR images (Fig. 5.30). Radial reformatted MR images are of particular value in this respect because they allow optimal visualization of the anterosuperior region of the femoral head/neck junction, where the most significant changes in the alpha angle occur (see Fig. 5.27). The normal alpha angle should not exceed 50 degrees. The larger the alpha angle, the more pronounced is nonspherical shape of the femoral head, and the greater is predisposition for anterior FAI.

Figure 5.13 ▪ Postel coxarthropathy. A: Osteoarthritis of the right hip joint in this 61-year-old woman markedly progressed in a very short time as seen on the radiograph obtained 5 months later (B). |

gross deformities of the knees are become obvious, such as valgus or varus configuration (Fig. 5.31).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree