Diagnostic Breast Imaging

Adenosis tumor

Air gap

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND)

Cat scratch disease

Columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts and secretions (CAPSS)

Complex fibroadenoma

Complex sclerosing lesion (CSL)

Cyst

Diabetic fibrous mastopathy

Double spot compression magnification views

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

Epidermal inclusion cyst

Extensive intraductal component (EIC)

Extra-abdominal desmoid

Extracapsular tumor extension

Fat necrosis

Fibroadenoma

Fibromatosis

Focal fibrosis

Focal spot

Galactocele

Granular cell tumor

Gynecomastia

Hematoma

Invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS)

Invasive lobular carcinoma

Lactational adenoma

Lipoma

Lobular neoplasia

Lymphovascular space involvement

Male breast cancer

Mastitis

Medullary carcinoma

Metachronous carcinoma

Metaplastic carcinoma

Metastatic disease

Milk of calcium

Mucinous carcinoma

Multiple peripheral papillomas

Neoadjuvant therapy

Oil cyst

Papillary carcinoma

Papilloma

Perineural invasion

Peripheral abscess

Phyllodes tumor

Port-a-catheters

Posttraumatic change

Pneumocystography

Probably benign lesion

Psammoma bodies

Pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH)

Radial scar

Sclerosing adenosis

Sebaceous cyst

Secretory calcification

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB)

Shrinking breast

Spot compression views

Spot tangential views

Subareolar abscess

Synchronous carcinoma

Touch imprints

Triangulation of lesion location

Tubular adenoma

Tubular carcinoma

Tubulolobular carcinoma

Tumor necrosis

Vascular calcification

The diagnostic patient population is made up of women called back for potential abnormalities detected on a screening mammogram, patients who present with signs and symptoms of disease localized to the breast(s), patients with a history of breast cancer treated with lumpectomy and radiation therapy, and those undergoing follow-up during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. At some facilities, and according to the American College of Radiology (ACR) Practice Guideline for the Performance of Diagnostic Mammography, women with implants may also be included in the diagnostic patient population.

This chapter describes one approach to the diagnostic evaluation of patients with breast related findings, which I have developed and

fine-tuned through years of experience and thousands of patient encounters. I provide the rationale for a common-sense, streamlined approach and illustrate principles that I think you will find practical, efficient, and helpful in minimizing a delay in a breast cancer diagnosis. Simplicity, creativity, and resourcefulness in problem solving are all components of the approach. Obviously, there are many different ways of approaching this patient population, and again my recommendation is that you select a method that works in your hands, and use it consistently. Do not short-circuit evaluations for the sake of expediency, be flexible and creative (but keep it simple) in sorting through dilemmas, make no assumptions, and demand the highest quality possible from yourself and those around you.

fine-tuned through years of experience and thousands of patient encounters. I provide the rationale for a common-sense, streamlined approach and illustrate principles that I think you will find practical, efficient, and helpful in minimizing a delay in a breast cancer diagnosis. Simplicity, creativity, and resourcefulness in problem solving are all components of the approach. Obviously, there are many different ways of approaching this patient population, and again my recommendation is that you select a method that works in your hands, and use it consistently. Do not short-circuit evaluations for the sake of expediency, be flexible and creative (but keep it simple) in sorting through dilemmas, make no assumptions, and demand the highest quality possible from yourself and those around you.

Although I provide the imaging algorithms I use, a dedicated breast imaging radiologist directs all diagnostic evaluations and can tailor the exam to the patient and the problem being evaluated. Results, impressions, and recommendations are discussed with the patient directly at the time of the evaluation. Tools available to evaluate patients include mammographic images, correlative physical examination, ultrasound, cyst aspiration, pneumocystography, ductography, imaging-guided fine-needle aspiration, and imaging-guided needle biopsy. If indicated, magnetic resonance imaging of the breast is scheduled at the time of the patient’s diagnostic evaluation, including all patients diagnosed with breast cancer following an imaging-guided procedure.

For patients called back after screening, additional mammographic images are almost always taken. Virtually all of the additional views imaged during diagnostic evaluations involve the use of the spot compression paddle and include spot compression, rolled spot compression, spot tangential, and double spot compression magnification views. Spot compression and rolled compression views are taken when trying to determine if a lesion is present (or is it merely an “imaginoma”), when establishing the marginal characteristics of a mass, or, with rolled views, for triangulating the location of a lesion seen initially on only one of the routine views. Spot tangential views are taken routinely in evaluating focal signs and symptoms. They are also used when a lesion is thought to be localized to the skin or to position postoperative skin changes following lumpectomy and radiation, in tangent to the x-ray beam so that they are not superimposed and potentially obscuring significant changes at the lumpectomy bed. Double spot compression magnification views are indicated when evaluating calcifications. The only diagnostic images that are sometimes done with the large compression paddle are lateral views (90-degree lateromedial or 90-degree mediolateral views) used to triangulate the location of a lesion on the orthogonal view. As with screening views, high-quality, well-exposed, high-contrast diagnostic images, with no blur or artifacts, are essential to minimize the likelihood of delaying or missing a breast cancer diagnosis.

When women over the age of 30 years present with a “lump” or other focal symptom (focal pain, skin change, nipple retraction, etc.), a metallic BB is placed at the site of focal concern. Then craniocaudal (CC) and mediolateral oblique (MLO) views are imaged bilaterally, as well as a spot tangential view of the focal abnormality. A unilateral study (CC and MLO views) of the symptomatic breast with the spot tangential view at the site of focal concern is done if the patient has had a mammogram within the preceding 6 months. Based on what is seen on these initial images, additional spot compression, or double spot compression magnification views, may be oftained. Depending on the location of the focal finding, and the appearance of this area on the spot tangential view, correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are usually indicated. The ultrasound may be deferred in patients in whom there is no chance that the lesion has been excluded from the field of view and completely fatty tissue, or a benign lesion (e.g., an oil cyst or a dystrophic calcification), is imaged corresponding to the area of concern.

For women under the age of 30 years, or who are pregnant or lactating, who present with a “lump” or other focal symptom, we start by doing a physical examination and an ultrasound. In most of these patients, this is all that is required for an appropriate disposition. Rarely, if a breast cancer is suspected based on the physical exam and ultrasound findings, a biopsy may be indicated in this patient population. If cancer is suspected, a full bilateral mammogram is also done.

When patients present for diagnostic evaluations, our goal is to establish the correct diagnosis, accurately and efficiently, so we do as much as is indicated and the patient desires, in one visit. For some women this may include mammographic images only, or additional views and an ultrasound; for other patients, additional mammographic views, an ultrasound, and a core biopsy are performed. In my experience, if a biopsy is indicated, the patient’s immediate question is “How soon can I have it done?” and they are appreciative (and in many ways relieved) when I respond, “If you would like, we can do the biopsy now and have results by tomorrow.” Rarely, a patient requests time to discuss the recommendation with her family; in that case, we schedule the biopsy for a date that is convenient for the patient.

Histologic findings are discussed by the radiologist and the pathologist who review the cores within 24 hours of the core biopsy, so patients are asked to return the following business day to receive their results. The biopsy site is examined, biopsy results are discussed, and, based on the results, our recommendations regarding the need to return to screening guidelines, short-interval follow-up, excisional biopsy, or surgical consultation are discussed with the patient. If a surgical consultation is indicated, this is scheduled for the patient before she leaves our center. With a commitment from the breast surgeon, patients are seen within 48 hours of a breast cancer diagnosis.

Under the Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA), all reports involving mammographic images require an assessment category. Our approach, however, is to provide an assessment that

reflects our recommendation following the completed diagnostic evaluation. This usually incorporates the findings and impression formulated following the physical examination, mammogram, and ultrasound (or other studies that may be done). So, in addition to using BI-RADS® categories 1 and 2, and category 3 (probably benign, short-interval follow-up), we also use category 4 (suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered) and category 5 (highly suggestive of malignancy—appropriate action should be taken), based on what is determined following the completed diagnostic evaluation. Based on the likelihood of malignancy, category 4 lesions can be subclassified into 4A (low suspicion for malignancy), 4B (intermediate suspicion for malignancy), or 4C (moderate concern, but not classic as in category 5). Category 0 is used for patients for whom we schedule magnetic resonance imaging for further evaluation, and BI-RADS® category 6 (known malignancy) is used primarily for patients with a breast cancer diagnosis who are receiving chemotherapy (e.g., neoadjuvant therapy) and are undergoing monitoring of chemotherapy response. Although in this text I use the ACR lexicon terminology, in our practice we have chosen to vary the verbiage provided with categories 4 and 5 to indicate that a “biopsy is indicated” rather than “should be considered” or “appropriate action should be taken” (more on this below).

reflects our recommendation following the completed diagnostic evaluation. This usually incorporates the findings and impression formulated following the physical examination, mammogram, and ultrasound (or other studies that may be done). So, in addition to using BI-RADS® categories 1 and 2, and category 3 (probably benign, short-interval follow-up), we also use category 4 (suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered) and category 5 (highly suggestive of malignancy—appropriate action should be taken), based on what is determined following the completed diagnostic evaluation. Based on the likelihood of malignancy, category 4 lesions can be subclassified into 4A (low suspicion for malignancy), 4B (intermediate suspicion for malignancy), or 4C (moderate concern, but not classic as in category 5). Category 0 is used for patients for whom we schedule magnetic resonance imaging for further evaluation, and BI-RADS® category 6 (known malignancy) is used primarily for patients with a breast cancer diagnosis who are receiving chemotherapy (e.g., neoadjuvant therapy) and are undergoing monitoring of chemotherapy response. Although in this text I use the ACR lexicon terminology, in our practice we have chosen to vary the verbiage provided with categories 4 and 5 to indicate that a “biopsy is indicated” rather than “should be considered” or “appropriate action should be taken” (more on this below).

Before going further, please indulge me in a short philosophical discussion about how we, as radiologists, choose to practice breast imaging. Although some are likely to disagree with several (and maybe all) of the concepts presented here, in generating a reaction, one way or the other, I accomplish my goal of getting you to think about issues that are not usually thought about—but perhaps should be.

As radiologists, we can effectively choose to delegate many of our responsibilities as physicians to others, thereby minimizing our direct role in the care of patients. We work hard during screening to identify small breast cancers, yet we routinely relegate the role of discussing our findings with patients to others. With this comes an obfuscation of our critical role in the detection of clinically occult early-stage breast cancer and possible misrepresentations to patients relative to the limitations of mammography and the generation of unrealistic expectations regarding the appropriateness of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. We struggle during diagnostic evaluations to arrive at an answer, yet we dismiss patients with lines such as “You will get the results from your doctor,” as though we are incapable (or unwilling) to do it, or we avoid all direct contact with the patient and have one of our surrogates tell the patient that she should contact her physician for the results. We identify potential cancers, yet we won’t do the biopsy while the patient is in our facility because it is not practical or expedient. Patients are asked to wait for days and sometimes weeks for a biopsy to be done and then for results. If we do the biopsy, we often relegate patient follow-up and the discussion of results to the referring physician or surgeon. How can this be acceptable? Imagine the anguish. Is it any wonder that radiologists are the physicians most commonly named in malpractice lawsuits for delays in the diagnosis of breast cancer? I would argue that, in breast imaging, we are in a position to revolutionize and substantially improve patient care. Carpe diem.

What, then, should our role be? Should our role be to interpret films in isolation, or should it be that of clinicians and consultants who interpret breast images? I consider my role to be that of a clinical consultant in breast imaging (rather than a radiology report, I dictate “breast imaging consultations”), and as such, the patients who come to see me are my patients. In the diagnostic setting, rather than accept the history and physical examination described by others, I talk to the patients directly and, when indicated, undertake a physical examination. As opposed to delegating the breast ultrasound study to a technologist, I view this as an opportunity to establish effective rapport with the patient, review the history provided, and undertake correlative physical examination (in effect, placing eyeballs at the tips of my fingers). Why not take this opportunity? We place a significant amount of importance on what our images show, but shun the information provided by the physical examination and by talking directly with the patient. This information can be just as critical and important in arriving at the right answer as any finding on our imaging studies. There are times when the imaging studies are negative or equivocal and a biopsy is indicated based on clinical findings.

As I scan during the ultrasound study, I examine and talk with the patient. In addition to the visual information from the ultrasound, I find that use of the ultrasound coupling gel to examine a patient enhances my ability to find, feel, and characterize palpable findings. During the real-time portion of the study, as I scan and examine the patient, I determine if a lesion is present. After making this determination, I take the images needed to adequately and appropriately document the features of the lesion and that support the impression I formulate during the real-time portion of the study (i.e., directed image taking). I do not take pictures of normal tissue. Time and time again, I am impressed with how often the history obtained during these interchanges yields critical information used to establish the “true” nature and significance of what is going on. The other critical aspect of these interchanges is that it allows me to gauge the reaction of the patient to my recommendations. I want patients to understand and feel comfortable with what is happening. There are some who say we cannot afford to do this (i.e., it is not cost-effective). My response is to ask how can we afford not to do this? I would argue that it is more efficient and cost-effective, and I am convinced that this approach actually expedites high-quality patient care.

For a moment, consider patients referred to any specialist for a consultation. If a gastroenterologist detects a polyp during a colonoscopy, does he pull the scope out and dictate: “suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered?” or “finding highly suggestive of malignancy—appropriate action should be taken”? Likewise, if a cardiologist detects a significant coronary lesion that can be managed effectively with an angioplasty, does she call the referring physician for “permission” to proceed with an indicated procedure? No, they go ahead and do what needs to be done to take care of the patient. Why do we not consider a patient being sent to a breast imaging radiologist for evaluation in a similar light as a patient being sent to a breast surgeon for evaluation? Surgeons routinely do fine-needle aspirations and excisional biopsies on patients referred to them for clinical findings, even when fatty tissue is imaged mammographically and sonographically. This is acceptable, yet, on a mammogram with pleomorphic, linear casting-type calcifications, or a clinically occult 6-mm spiculated mass, we are expected to say “biopsy should be considered” or “appropriate action should be

taken”? Considered by whom and when? Appropriate action to be taken by whom and when?

taken”? Considered by whom and when? Appropriate action to be taken by whom and when?

As a consultant, therefore, I exercise the right to discuss all aspects of a patient’s breast-related findings, options for diagnosis (and treatment when appropriate), and, most important, I make specific recommendations and manage patients accordingly. In conjunction with the patient’s physician, I make referrals when indicated. Following biopsies, I provide all patients with my business card and cell phone number so they can contact me if they have questions or concerns, and I ask them to return the following business day for the results of the biopsy. During the post biopsy visit, I examine the biopsy site and, most important, discuss the results of the biopsy directly with the patient. I discuss all options with the patient, but I follow this with a specific recommendation for what I think is the next appropriate step. When indicated, and following a discussion with the patient’s physician, I make referrals so that the patient is helped and expedited through the system. Our patients are hungry for time, a warm touch, information, guidance, and yes, what we think is indicated.

Consider how you approach patients. I suggest that proper attire, including a white coat with your name badge clearly visible, is critical in sending a powerful message to patients. Scrubs belong in the operating room or the interventional suite, not when approaching a patient relative to a possible breast cancer diagnosis. Also, although things like jeans and chewing gum may be acceptable in recreational venues, they are not when you are doing an ultrasound or an imaging-guided biopsy on a patient who is watching you like a hawk, waiting for some feedback. Address patients by their title and last name; unless specifically requested by the woman, patients should not be addressed by their first name, and terms of endearment should not be used (this applies to the technologists as well). Introduce yourself to the patient and shake her hand. Before starting the examination, ask her one or two questions relative to her concerns. If the patient has been called back for a potential abnormality on the screening study, and you have done additional mammographic images, tell her what you have seen so far and explain what you would like to do next. If you are doing an ultrasound, let the patient watch the screen, and keep an eye on her. If she is watching the screen as you scan, involve her in the study by educating her on what you are looking at. The ribs can be used to show her what a “tumor” would look like. Try to make sure the patient understands and is comfortable with what you recommend, and never let an angry patient leave your facility. Talk to her and find out what you can do to make things better.

I think it is also important to consider some of the language that permeates our work. Although this sounds trivial, I think it negatively colors our perspective and helps impersonalize and distance us from our patients. Consider terms such as “cases,” “complaints,” “denies,” and “refuses.” Does it not subtly affect us if we view “cases as complainers who deny and refuse”? I see patients, not cases. Why do we choose to view what a patient presents with as a complaint? If you have a legitimate concern about something, does it not bother you even slightly if someone says you are complaining about it? If you have legitimate fears about something and want time to think and consider your options, or if you are afraid, is this refusing? Does it not turn us off when someone says, “She is refusing”? First, it is a patient’s right not to want something done, and this should always be respected and never judged negatively. Second, maybe if we worked harder to understand the patient’s concerns, we might be able to help her more effectively. Rather than close the door, leave it open so she feels she can walk back through it and you will be there to help her. Try never to judge patients and what they have chosen to do. Comments such as “How could she have let this go?” or “Can you believe that she is saying this just came up?” are not acceptable. Who are we to know what a patient is going through and what her reasons may be for making a decision? Little is accomplished, and I think we stand to lose much, by having a patient feel guilty about what she has chosen to do. Our job is not to judge her, but to help her today and put her in as positive a frame of mind as possible to deal with what she is facing. I urge you to consider and analyze everything that you say and do in approaching patients. Work hard and creatively to spin things in a positive light; rather than viewing what we do as a chore, we should view the trust patients place in us as an incredible privilege unlike few others afforded us in life. We should feel honored that patients have enough confidence in us to share some of their most personal information, fears, and concerns.

You set the tone for your facility, and insisting that everyone in your facility think of patients as presenting with legitimate concerns and having the right to forgo a procedure has a positive effect on how everyone approaches his or her job and our patients.

Lastly, I want to emphasize the need for communication and appropriate documentation. Communicate directly with patients, referring physicians, pathologists, surgeons, and medical oncologists. Demand to speak directly with the physician (“I do not take no for an answer.”). It is critical that referring physicians be kept in the loop, particularly in relation to a breast cancer diagnosis in one of their patients. Relative to pathology results, talk directly with the pathologist signing out a fine-needle aspiration or core biopsy. If possible, visit the pathology lab and review the histology of some of the more interesting cases you may diagnose. These interchanges can be incredibly valuable learning tools, and by working together, decisions can be made as to the adequacy of sampling or any lingering concerns the pathologist may have that might alter your management of the patient. Discuss specimen radiography results directly with the surgeon while the patient is still in the operating room (e.g., are you concerned that a lesion may extend to the margins, or are you concerned that the lesion, or your localization wire, has not been excised?).

I document the date, time, and nature of all communication (if possible with direct quotes) on the patient’s history form (not in the breast imaging consultation report). Invest time in teaching your clerical and technical staff how to document encounters with patients properly. Months or years down the road, appropriate documentation can be critical in dealing with unresolved patient issues. Documentation needs to be appropriate, factual, and nonjudgmental. Documentation should not be a reflection of how your employee felt or saw a situation but rather a narrative of what happened. Provide the information accurately and let the reader formulate the impression. These simple steps cost little and yet the rewards in good patient care, goodwill, and public relations can be significant (as intangible as they may seem).

Patient 1

What do you think, and what would you do next?

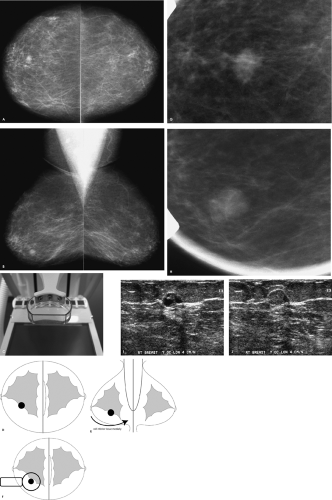

A mass is present in the right breast. Before recommending any additional evaluation, you should inquire about prior films. If prior films are available, and this mass is stable, decreasing in size, or has been previously evaluated, no additional intervention may be warranted at this time. Because this patient has no prior films, she is called back for additional evaluation, including spot compression views, correlative physical examination, and sonography.

BI-RADS® category 0: need additional imaging evaluation.

Why use a spot compression paddle, and what are the indications for spot compression views?

What is critical to consider when evaluating the adequacy of spot compression views?

Why?

The spot compression paddle enables the application of maximal compression to a small area of the breast so that tissue is spread out and the area of radiographic concern is brought closer to the film, thereby improving resolution and image quality; it can help reach areas that are otherwise difficult to include when the large compression paddle is used. Spot compression views are helpful in several different situations in the diagnostic evaluation of patients. In some patients, spot compression views are used to distinguish a mass or distortion from normal superimposed glandular tissue. If a mass is detected on routine views, spot compression views can help characterize the marginal characteristics of the mass by displacing obscuring superimposed tissue.

In screening and diagnostic situations, spot compression views can be helpful in evaluating the subareolar area, particularly if compression of the anterior aspect of the breast is limited by the thickness of the base of the breast. If there is an area of relatively dense tissue that is underexposed, using the spot compression paddle may be helpful in improving the exposure by effectively decreasing the thickness of the tissue requiring penetration. In evaluating spot compression views, it is important to ensure that the area in question is included on the view; masses can sometimes be “squeezed” (or pulled) out from under the paddle and not imaged. As with routine views, spot compression views need to be well exposed, high in contrast, and free of motion blur.

When are rolled spot compression views used?

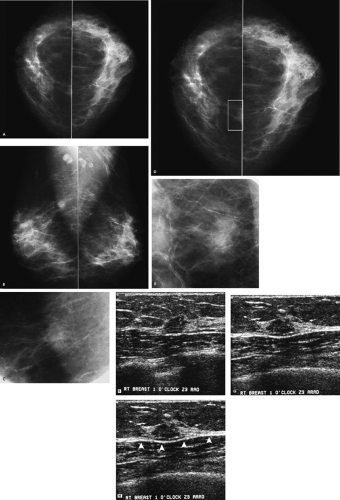

Rolled spot compression (i.e., change-of-angle) views are an additional tool available for establishing the existence of a lesion. Most tumors are three-dimensional and maintain their tumorlike shape as tissue is rolled. In contrast, breast tissue and focal areas of parenchymal asymmetry change in size, shape, and overall density as tissue is moved. Rolled spot compression views can also be used to move (roll) lesions away from surrounding tissue so that the marginal characteristics can be demonstrated to better advantage (Fig. 3.1D–F). Lastly, rolled spot compression views can be used to establish the approximate location of a lesion in the breast. If a lesion is located in the medial aspect of the breast, it will move with medial tissue. Similarly, if a lesion is in the lower outer quadrant of the breast, it will move with the tissue in the lower outer quadrant of the breast.

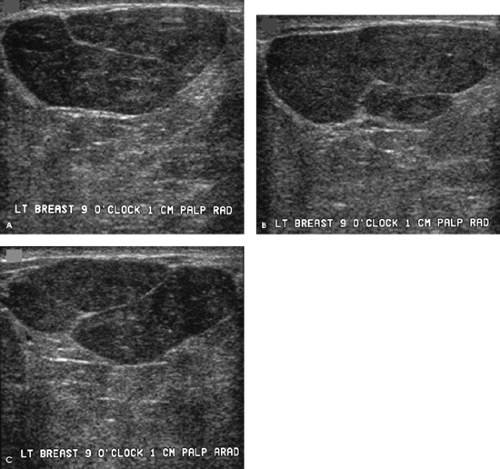

How would you describe the imaging findings, and what differential would you consider?

The margins of this 1-cm mass are indistinct on the craniocaudal spot compression view and more circumscribed on the mediolateral oblique spot compression view. On ultrasound, this nearly isoechoic oval mass is well circumscribed with posterior acoustic enhancement and associated cystic changes.

Benign diagnostic considerations include fibroadenoma (tubular adenoma, complex fibroadenoma), phyllodes tumor, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), focal fibrosis, papilloma, an inflammatory lesion, or, in certain clinical contexts (recent trauma or surgery), a hematoma. A granular cell tumor is a rare possibility. Malignant considerations include invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, mucinous carcinoma, papillary carcinoma, or a metastatic lesion. A biopsy is indicated.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

Rather than just consider a biopsy, one is performed, and a complex fibroadenoma is diagnosed. The patient is asked to return in 1 year for her next screening mammogram.

Complex fibroadenomas are defined as fibroadenomas with superimposed fibrocystic changes including cysts > 3 mm in size, sclerosing adenosis, epithelial calcifications, and papillary apocrine changes. They can be anticipated when cystic changes are noted in an otherwise well-circumscribed oval mass such as the one demonstrated here, or when round, punctuate, or amorphous calcifications are identified in an otherwise well-circumscribed mass mammographically (i.e., the punctate and amorphous calcifications reflect the presence of sclerosing adenosis). In some patients, no distinctive imaging features are identified to suggest a complex fibroadenoma. These lesions are benign and do not warrant any additional intervention following core biopsy. Approximately 33% of all fibroadenomas have been reported as complex. When proliferative changes are present in the stroma surrounding a complex fibroadenoma, the risk of breast cancer has been reported to be increased 3.88 times.

Patient 2

What is an appropriate approach to patients who describe a localized concern (a “lump,” focal skin changes, pinpoint tenderness, etc.)?

For patients who are 30 years of age or older and who present with a palpable abnormality (or other localized finding), a metallic BB is placed at the site of the focal finding and a bilateral mammogram is done; a unilateral study of the symptomatic breast is done if the patient has had a mammogram within the last 6 months. A spot tangential view at the site of the focal abnormality is obtained in conjunction with the routine views. In many patients, the tangential view is helpful in either partially or completely outlining the lesion with subcutaneous fat, enabling better visualization and characterization of the lesion. If needed, additional spot compression or spot compression magnification views can be done. Depending on the location of the focal finding, and the appearance of this area on the spot tangential view, correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are usually indicated. The ultrasound may be deferred in patients in whom there is no chance the lesion has been excluded from the field of view and completely fatty tissue, or a benign lesion (oil cyst, dystrophic calcification, etc.), is imaged corresponding to the area of concern. Aspiration or core biopsy may be indicated, depending on the clinical and imaging features of the lesion.

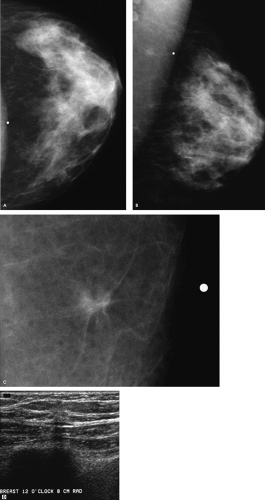

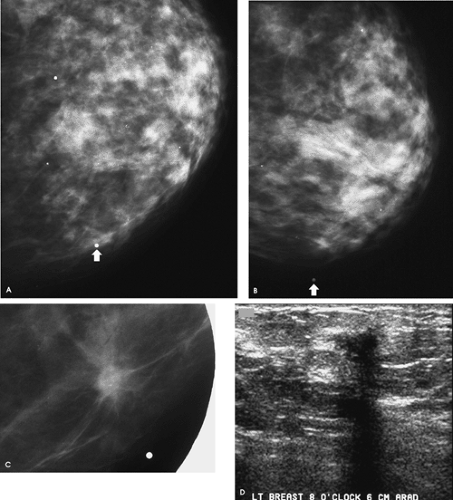

How would you describe the findings on the routine views of this patient, and with what degree of certainty can you make any recommendations?

Although there is a small island of tissue superimposed on the left pectoral muscle in close proximity to the metallic BB, no definite abnormality is apparent on the routine views of the left breast. At this point, we have an inadequate amount of information to make any justifiable recommendations. We need to review the spot tangential view of the “lump,” talk to the patient, undertake correlative physical examination, and do an ultrasound.

What do you think now?

A 7-mm spiculated mass associated with punctate, low-density calcifications is imaged on the spot tangential view corresponding to the palpable finding. A discrete, hard mass is palpated at the site indicated by the patient in the left breast. She has not had a prior biopsy or trauma to this site, and no tenderness is elicited on palpation. On ultrasound, a small hypoechoic mass with disruption of the Cooper ligament is identified at the 12 o’clock position, 8 cm from the left nipple, corresponding to the palpable abnormality. Although the finding is subtle on ultrasound, with careful and meticulous technique it is discernable and reproducibly imaged as the palpable area is scanned. In positioning patients for the ultrasound study, I try to thin the area of the breast being evaluated as much as possible. In evaluating lateral lesions, the patient is placed in an oblique position with a wedge under the ipsilateral arm, and for medial lesions she is supine. If the patient

says she feels the “lump” more when she is upright, I will palpate and scan the area with her sitting as well as lying down. During the ultrasound study, I hold the transducer with my right hand and I place the pads of my left index, ring, and middle fingers at the leading edge of the transducer so that I am palpating the tissue as I rotate and move the transducer with my right hand. I apply varying amounts of compression as I manipulate the transducer directly over the area of clinical or mammographic concern.

says she feels the “lump” more when she is upright, I will palpate and scan the area with her sitting as well as lying down. During the ultrasound study, I hold the transducer with my right hand and I place the pads of my left index, ring, and middle fingers at the leading edge of the transducer so that I am palpating the tissue as I rotate and move the transducer with my right hand. I apply varying amounts of compression as I manipulate the transducer directly over the area of clinical or mammographic concern.

What is your differential diagnosis, and what recommendation should you make to the patient?

Differential considerations for the findings include invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), tubular carcinoma, and invasive lobular carcinoma. Benign considerations include fat necrosis (posttrauma or postsurgery), sclerosing adenosis, papilloma, focal fibrosis, a complex sclerosing lesion, and inflammatory changes (mastitis). Other rare benign causes include granular cell tumor or an extra-abdominal desmoid.

A biopsy is indicated.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

An ultrasound-guided biopsy is done, and an invasive mammary carcinoma with features suggestive of tubular carcinoma is described on the core samples. A tubular carcinoma is confirmed following the lumpectomy. Sampled lymph nodes are normal (pT1b, pN0, pMX; Stage I).

In considering tubular carcinoma, what associated lesions may be seen and what should you look for mammographically?

The reported incidence of tubular carcinomas varies depending on detection method, tumor size, and the definition used to classify these tumors. Pure tubular carcinomas probably represent 1% to 2% of all breast cancers. Tubular carcinomas are usually detected mammographically as a small spiculated mass; less commonly, patients present with a palpable mass. Associated round, punctate, and amorphous calcifications may be seen, reflecting the presence of low-nuclear-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (solid, cribriform, and micropapillary), in an average of 65% of patients. Satellite lesions may also be seen, because these lesions may be multifocal or multicentric in 10% to 20% (reportedly as high as 56% in one small series) of patients. Lobular neoplasia (lobular carcinoma in situ), contralateral invasive ductal carcinomas NOS, and a history of breast cancer in a first-degree relative have been reported in as many as 15% (range 0.7% to 40%), 38%, and 40% of patients diagnosed with tubular carcinoma, respectively.

What distinguishes the glands seen in tubular carcinomas from normal glands?

Histologically, what are the differential considerations for this lesion?

Histologically, these lesions are characterized by the presence of oval and round, open tubules some with angulation. The glands in tubular carcinomas are lined by a single epithelial cell layer and, in contrast to normal glands, lack myoepithelial cells. Desmoplastic changes are noted in the surrounding stroma and probably explain the imaging features of these lesions (i.e., spiculation). Tubular carcinomas may be difficult to distinguish from radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions (in some patients, tubular carcinomas arise in radial scars/complex sclerosing lesions), sclerosing adenosis, and microglandular adenosis. Special immunohistochemical stains are sometimes needed to assess the presence of myoepithelial cells. These tumors are often diploid, estrogen- and progesterone-receptor-positive, and only rarely over-express HER-2 neu.

Why is listening, correlating physical and imaging findings, and establishing rapport with your patients so important?

Complete, thoughtful evaluations are indicated for all patients, but particularly those presenting with focal signs and symptoms. Radiologists as a group are the most commonly sued physicians, and delays in the diagnosis of breast cancer are the most common causes of malpractice claims filed. Interestingly, the suits are not usually (at least not yet) for missing subtle mammographic findings, but rather for clinically apparent findings the patient feels were ignored. I urge you to establish a good rapport with your patients, listen to their concerns, and make every effort possible to help them. Not only is this good medicine, it makes for a rewarding and fulfilling practice opportunity. You do not want patients leaving your facility angry and feeling that their concerns were ignored or not adequately evaluated. Do not short-circuit appropriate and logical mammographic workups. Make sure that what is seen mammographically correlates with the clinical findings. In making sure that what is seen on ultrasound correlates with the mammographic findings you are evaluating, determine the expected clock position of the lesion and its approximate distance from the nipplebefore going into the ultrasound room; this location should be the starting point for the ultrasound study.

While examining the patient and correlating clinical, mammographic, and ultrasound findings, I obtain a more detailed history from the patient. This is also a good time to convey to the patient what I am doing on her behalf, to discuss recommendations, determine if the patient is comfortable with my recommendations, and answer her questions. Although some consider it inefficient for a radiologist to do the ultrasound studies personally, I argue that it is more efficient and it makes for good patient care.

During the real-time scan, and before taking any images, I determine if there is an identifiable abnormality by examining the patient as I rotate the transducer and apply varying amounts of compression over the area of concern. The 360-degree rotation of the transducer is critical in excluding pseudolesions created by areas of fatty lobulation, which in one plane may look round or oval but elongate and fuse with surrounding tissue as you rotate the transducer. A real mass maintains a round or oval shape as you rotate the transducer directly over it. Applying variable amounts of compression over an area can help eliminate critical angle shadowing that may limit the evaluation of deeper tissue. If I determine that a lesion is present, I take orthogonal images (with and without measurements) that demonstrate representative features of the lesion. In some women, this may require radial and antiradial projections, whereas in others, transverse and longitudinal (i.e., sagittal) orientations show the lesion and its characteristics to better advantage. I use the images taken to support my impression and justify my recommendations. I take no images of normal tissue. In annotating the images, the breast being scanned is indicated, as is the clock position of the lesion and its distance in centimeters from the nipple.

Patient 3

What is an acceptable approach to patients who present with focal findings?

In evaluating the adequacy of spot tangential views, what should you consider?

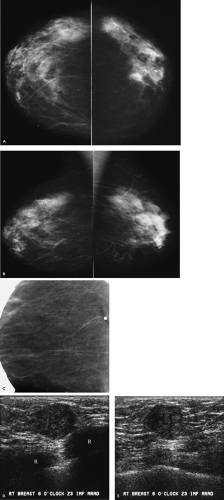

In patients who are 30 years of age or older and who present with a palpable abnormality (or other localized finding), a metallic BB is placed at the site of concern, and routine views are done bilaterally unless the patient has had a mammogram in the preceding 6 months, in which case a unilateral mammogram of the symptomatic breast is done. In addition, a spot tangential view of the focal finding is done. In many patients, the tangential view is helpful in either partially or completely outlining the lesion, with subcutaneous fat facilitating characterization. Depending on the location of the focal finding, and the appearance of this area on the spot tangential view, correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are usually indicated. Ultrasound may be deferred in patients in whom there is no chance the lesion has been excluded from the tangential view and completely fatty tissue, or a benign lesion, is imaged corresponding to the palpable abnormality.

In this patient, do you see the metallic BB on the routine views of the right breast? Why not? In this patient, the palpable finding is deep in the breast, just above the inframammary fold. The metallic BB was placed on the “lump” but has been excluded from the field of view. The metallic BB is seen on the spot tangential view, and predominantly fatty tissue is imaged on the spot tangential view. In this patient, the possibility that the lesion has been excluded from the images is a real concern. As with all spot compression views, you need to consider the possibility that the lesion has been squeezed out of the field of view or, because of its location, is not included on the images. Correlative physical examination in this patient confirms the presence of a palpable mass fixed at the inframammary fold. Also noted are arterial calcifications in the left breast and coarse, dense, benign-type calcifications anteriorly in the right breast.

How would you describe the ultrasound findings, and what is indicated in this patient?

A round, 1.2-cm hypoechoic mass with partially indistinct margins and associated posterior acoustic enhancement is imaged corresponding to the palpable finding at the 6 o’clock position, posteriorly (Z3) in the right breast. The lesion is just below the skin and snuggled in close proximity to the ribs (R). An invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, mucinous carcinoma, papillary carcinoma, or a metastatic lesion are the primary considerations in an 80-year-old patient presenting with these findings.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

A mucinous carcinoma is diagnosed on the ultrasound core biopsy. A 1.3-cm mucinous carcinoma with associated intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ is confirmed on the lumpectomy specimen. The sentinel lymph node is negative for metastatic disease (pT1c, pN0(sn) (i—), pMX; Stage I).

What are some of the tools available in evaluating lesions possibly excluded from the routine views?

Lesions close to the chest wall (far superior, inferior, lateral, or medial) and lesions high in the axilla may not be included on routine or spot compression views of the breast. Anytime you suspect that a lesion is potentially excluded from the mammographic images, or there are potential factors limiting compression, correlative physical examination and ultrasound are wonderful adjunctive tools. Also, capitalize on basic concepts such as the use of various projections to position tissue as close to the film as possible. If you think a lesion is medial in location, consider a 90-degree lateromedial (LM) spot compression so that medial tissue is placed up against the film; this minimizes the possibility of exclusion because medial tissue is up against the film, and it improves resolution by placing the area of concern closest to the film. Likewise, if you think a lesion is high up in the breast, have the technologist do a from-below (FB) view such that superior tissue is now closest to the film. If you suspect a lesion is at, or just below, the inframammary fold (IMF), tell the technologist not to lift the breast as she positions for the craniocaudal (CC) view. She should place the film holder at the neutral position for the IMF, because as the breast is lifted at the IMF for the routine CC view, the mass may be able to slip out and not be included on the image. Remember, the use of the spot compression paddle usually makes it easier to include more posterior, superior, or axillary tissue in the field of view. In evaluating potential lesions in the axillary tail, an axillary view can be useful.

Patient 4

What is an appropriate evaluation of patients with screening-detected calcifications that cannot be classified as benign on the routine views?

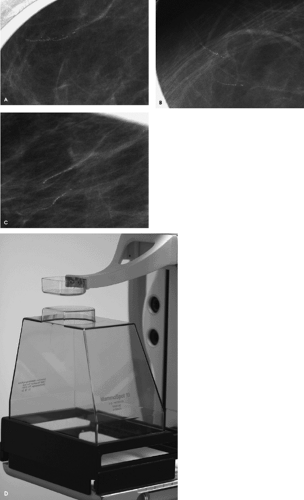

The next step should be magnification views. Specifically, our protocol uses double spot compression magnification views in orthogonal projections to evaluate women with indeterminate calcifications detected on routine mammographic views.

How is magnification obtained, and what are the resulting effects?

Magnification technique is accomplished by increasing the distance between the breast (i.e., object) and film. The resulting air gap helps to eliminate scatter radiation, so a grid is not needed for magnification views. Compared with the 0.3-mm focal spot used for routine (nonmagnified) mammographic views, a 0.1-mm focal spot is used for magnification views. The small focal spot is needed to minimize the penumbra effect that results as you increase the breast (object)-to-film distance. The use of the small focal spot, however, results in increased exposure times, so motion becomes a significant issue that may limit the usefulness of magnification views.

What can be done to minimize the likelihood of motion blur on magnification views?

Optimizing the system to obtain an adequate exposure in a short period of time is critical for routinely obtaining high-quality magnification views. An appropriate selection of voltage, a magnification stand that minimizes the amount of radiation absorbed, optimal focal compression, and working with the patient on controlling her breathing are simple steps that can improve overall image quality significantly.

As a general rule, the voltage used for exposure on magnification views is increased by 2 kV over that used for the routine, nonmagnified views. We do all of our magnification views using a Lexan®-top magnification stand (MammoSpot®, American Mammographics, Chattanooga, TN). Compared to standard carbon-top magnification stands, those made of Lexan® absorb less radiation, so exposure times can be decreased by as much as 40%.

Optimal compression is also critical for obtaining high-quality magnification views. This is why we advocate the use of double spot compression. The magnification stand has a built-in spot compression, which, when combined with the spot compression paddle, enables maximal compression of the tissue being evaluated (i.e., double spot compression). The technologist is also encouraged to work with the patient on breath holding (i.e., the patient should stop breathing when requested rather than taking a deep breath in) to minimize the likelihood of motion.

If you have determined that there is a need for magnification views, don’t settle for suboptimal quality and hide behind disclaimers. If the magnification views are not optimal, step back and review what the technologist is doing. Does the voltage need to be increased further (accepting that as you increase voltage, contrast is

decreased)? Is the correct focal spot being used? Can compression be increased? Can you work with the patient to improve breath holding? High-contrast, well-exposed, artifact-free magnification views are critical for assessing the morphology and extent of calcifications that may reflect the presence of ductal carcinoma in situ. Recognize that the ability to detect and characterize calcifications and small masses is significantly compromised (and may be eliminated) on images with blurring.

decreased)? Is the correct focal spot being used? Can compression be increased? Can you work with the patient to improve breath holding? High-contrast, well-exposed, artifact-free magnification views are critical for assessing the morphology and extent of calcifications that may reflect the presence of ductal carcinoma in situ. Recognize that the ability to detect and characterize calcifications and small masses is significantly compromised (and may be eliminated) on images with blurring.

How would you describe these calcifications in this patient, and what is your differential diagnosis?

What is indicated?

Round, punctate, and linear calcifications demonstrating linear orientation are confirmed on the double spot compression magnification views. The differential is limited but includes fibrocystic changes including columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts (CAPPS), ductal hyperplasia and atypical ductal hyperplasia, fibrosis, and ductal carcinoma in situ. In the absence of any other change related to trauma (e.g., mixed-density mass, oil cyst), or a specific history of trauma or surgery to the site of the calcifications, these calcifications are unlikely to represent an early stage of fat necrosis. Given the linear orientation of the calcifications, biopsy is indicated.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

Ductal carcinoma in situ is reported on the stereotactically guided biopsy and confirmed on the lumpectomy [Tis(DCIS), pNX, pMX; Stage 0].

Patient 5

What do you think, and what is your recommendation at this point?

Arterial calcifications are present bilaterally. A possible mass is present on the right mediolateral oblique (MLO) view superimposed on the pectoral muscle inferiorly. This should be distinguished from several well-circumscribed, mixed-density masses (i.e., lymph nodes) superimposed on the pectoral muscles, bilaterally. No definite corresponding abnormality is apparent on the right craniocaudal (CC) view. Comparison with prior studies is the starting point. If no prior films are available, or if this potential mass represents a change, additional evaluation is indicated.

BI-RADS® category 0: need additional imaging evaluation.

How would you approach the diagnostic evaluation of this patient?

Be specific in describing the steps you would follow

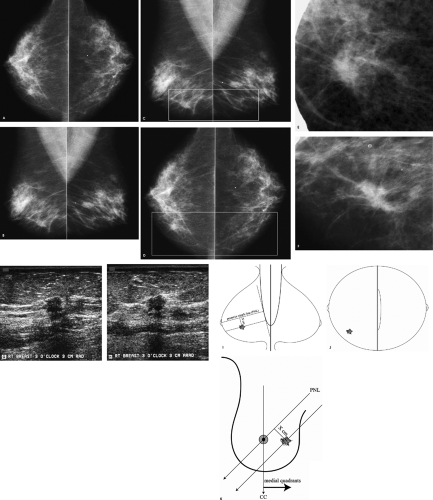

When a potential abnormality is seen in only one of the two standard views, we start by determining if the finding is real in the view in which it is initially perceived. In this patient, a spot compression view in the MLO projection is obtained. If no abnormality persists on the spot compression view, no additional views are done; if a question remains, rolled spot compression views can be done. In this patient, a 1.2-cm mass with indistinct margins is confirmed on the MLO spot compression view (Fig. 3.5C). We must now establish the location of this abnormality in the CC projection using a logical approach. We make no assumptions as to the lateral, central, or medial location of the lesion on the CC view. Rather, a 90-degree lateral view (usually a lateromedial view) is done to determine how this lesion moves with respect to its location on the MLO view. If the lesion moves up, it is located medially and a spot cleavage view is done; if the lesion moves down, it is located laterally such that a spot craniocaudal view exaggerated laterally is done; and if it does not move significantly, the lesion is central in location and a spot compression view directly behind the nipple is obtained. In this patient the lesion moves up (image not shown), consistent with a medial location. Upon further review of the C view, a density is partially noted on the craniocaudal view at the edge of the film medially (box, Fig. 3.5D). A follow-up image with the spot compression paddle enables visualization of more tissue so that the lesion is imaged in its entirety (Fig. 3.5E) in the CC projection.

How would you describe the ultrasound findings?

An irregular, 1.2-cm mass with indistinct, angular, and spiculated margins is imaged at the 1 o’clock position posteriorly (Z3), abutting the deep pectoral fascia (arrowheads, Fig. 3.5H). Straightening, thickening, and disruption of Cooper ligaments are noted. This mass corresponds to the mass seen mammographically.

What is your differential diagnosis, and what recommendation do you make to the patient?

Differential considerations include invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, invasive lobular carcinoma, or lymphoma. Rarely, ductal carcinoma in situ can present as a mass, asymmetric density, or distortion in the absence of microcalcifications. Benign considerations include an inflammatory process or posttraumatic changes, focal fibrosis, a papilloma, sclerosing adenosis, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia, granular cell tumor, or an extra-abdominal desmoid. Given the imaging features of this lesion, a biopsy is indicated.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

An ultrasound-guided biopsy is done. An invasive ductal carcinoma with associated ductal carcinoma in situ is diagnosed on the core biopsy.

A 1.5-cm, grade I invasive mammary carcinoma, with apocrine differentiation and an associated extensive, intermediate-grade (solid, cribriform patterns) ductal carcinoma in situ is reported on the lumpectomy specimen. Malignant cells are reported on a touch imprint of the sentinel lymph node done intraoperatively. Twenty additional nodes removed at the time of the lumpectomy are negative for metastatic disease (pT1c, pN1a, pMX; Stage IIA).

What are touch imprints, and how are they used at the time of the lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy?

Touch imprints of the excised sentinel lymph node(s) are commonly done intraoperatively at the time of the lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. The lymph node is sectioned and the cut edge is blotted on slides. The cytologic material on the slides is fixed, stained, and reviewed by the pathologist. If malignant cells are identified on the touch imprints, a complete axillary lymph node dissection is done at the time of the lumpectomy. However, metastatic disease is not excluded if the imprints are reported as benign; false-negative touch imprints are commonly associated with invasive lobular carcinoma. In patients in whom the imprint is negative but metastatic disease is identified in the permanent, hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections of the sentinel lymph node, a full axillary dissection is usually undertaken as a second operative procedure.

How is an extensive intraductal component defined, and what is its significance?

An extensive intraductal component (EIC) is described when an invasive ductal carcinoma has a prominent intraductal component within it or intraductal carcinoma is present in sections of otherwise normal adjacent tissue. This term also applies to lesions that are predominantly intraductal but have foci of invasion. An EIC may indicate the presence of residual disease 2 cm beyond the primary lesion in as many as 30% of patients and is associated with an increased incidence of local recurrence following breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy. Patients with tumors characterized by an extensive intraductal component may benefit from a wider resection. Tumors with EIC are reportedly more common in younger women.

Patient 6

How would you describe the two masses?

What would you do next?

Two masses are present in the right breast, corresponding to the “lumps” described by the patient. The margins of the anterior mass are well circumscribed on the spot compression views (only one shown). In comparison, the margins of the larger, posterior mass are not as sharp and, for a portion of the mass, are indistinct. In entertaining a differential, you need to consider that these may reflect the same or, possibly, different processes. Cyst(s), fibroadenoma(s), tubular adenoma(s), phyllodes tumor(s) papilloma(s), pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia (PASH), focal fibrosis, abscess(es), posttraumatic or postsurgical fluid collections, invasive ductal carcinoma(s), medullary carcinoma(s), mucinous carcinoma(s), papillary carcinoma(s), and metastatic lesion(s) are included in the differential. Correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated for further characterization of these lesions.

Although these masses are palpable, based on their location on the mammogram, at what clock position do you expect to find these lesions?

Be specific

The anterior mass is located at the 12:30 o’clock position, 4 cm from the right nipple. It is a 1.2-cm oval, well-circumscribed mass characterized by areas of enhancement and shadowing. Although projecting below the level of the nipple on the mediolateral oblique view, the posterior mass is located in the upper inner quadrant of the right breast at the 2 o’clock position, 8 cm from the nipple, and measures 3 cm. It is vertically oriented, markedly hypoechoic, with indistinct margins and some spiculation. Some posterior acoustic enhancement is present. The imaging features of the anterior mass suggest a benign process and those of the posterior mass suggest a malignancy. Biopsies are recommended for both lesions.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

A complex fibroadenoma is reported histologically for the anterior mass. An invasive mammary carcinoma is diagnosed for the posterior lesion. A 4-cm, metaplastic carcinoma with no heterologous elements and a normal sentinel lymph node biopsy are reported following surgery [pT2, pN0(sn) (i—), pMX, Stage IIB].

As you progress from the mammogram to doing the ultrasound, consider carefully and focus your attention on the anatomic location of the lesion being evaluated. Obviously, it is critically important to assure that the lesion seen on the mammogram correlates with what you find on the ultrasound study. To this end, review the mammographic images before scanning the patient, so that when you walk in to evaluate the patient you have the expected clock position and approximate distance from the nipple for the lesion being evaluated as your starting point.

On craniocaudal and 90-degree lateral views (LM and ML), the location of a lesion is anatomic with respect to the nipple. Medial, lateral, and central findings on craniocaudal views are located medially, laterally, and centrally (i.e., behind the nipple) in the breast. Superior and inferior findings with respect to the nipple are located in the upper and lower quadrants, respectively, on the 90-degree lateral view (Fig. 3.6F). On mediolateral oblique views, however, it is important to recognize that some lesions projecting below the level of the nipple are in an upper quadrant of the breast and some that project above the level of the nipple are in a lower quadrant (Fig. 3.6G–I).

Based on the CC and MLO views, the anatomic location of the lesion needs to be determined, to assure accurate correlation between what is seen on the mammogram and anything that may be found on the ultrasound study. The information on the CC and MLO views (taken with the patient upright and tissue pulled out away from the body) needs to be transposed to a patient who is now supine, or in a slight oblique position, for the ultrasound study. Approximating the clock position of a lesion in the breast can be facilitated (and learned) by using frontal diagrams of the breast, in conjunction with the location of the lesion on the CC and MLO views.

On a frontal diagram of the breast, the posterior nipple line (PNL) is drawn as extending from the upper inner quadrant to the lower outer quadrant of the breast, transecting the nipple (this defines the course of the x-ray beam when an MLO view is done). Next, reference the location of the lesion on the MLO view (Fig. 3.6J) with respect to the PNL. The lesions are how far above or below the posterior nipple line on the MLO view? The lines describing the location of the lesion, with respect to the PNL on the MLO view, are drawn on the frontal diagram (Fig. 3.6K). Using the location of the lesions on the CC view (Fig. 3.6L), you can now narrow down the clock location of the lesion along the course of the lines drawn on the frontal view (Fig. 3.6J). You can now walk into the ultrasound room and place the transducer at the expected clock position for each lesion and find them easily with the assurance that what you are imaging on ultrasound correlates with what is being seen mammographically.

Patient 7

At this point, what can you say and with what degree of certainty?

What else would you tell the technologist to do?

Scattered and some clustered round and punctate calcifications, as well as more dense, coarse, and some lucent-centered calcifications, are present. However, no definite abnormality is apparent on the craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views that corresponds to the site of concern to the patient. At this point, we have insufficient information to say anything definitive. A spot tangential view of the palpable finding may be helpful; if it is not, correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated.

When women who are over the age of 30 years present with a “lump” or other focal symptom (focal pain, skin change etc.), a metallic BB is placed at the site of focal concern. This is followed by craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique views, bilaterally, as well as a spot tangential view of the focal abnormality (a unilateral study of the symptomatic breast is done if the patient has had a mammogram within the last 6 months). Based on these initial images, additional spot compression or double spot compression magnification views may be done. Depending on the location of the focal finding, and the appearance of this area on the spot tangential view, correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are usually indicated.

How helpful is the tangential view of this patient?

At this point, what can you say and with what degree of certainty?

What BI-RADS® assessment category would you assign?

For this patient, the tangential view is helpful. A spiculated mass is now readily apparent, corresponding to the palpable finding. Unless the patient has had trauma, or surgery localized specifically to this area, or there are symptoms related to an inflammatory process, a biopsy is indicated and the likelihood of malignancy in an 82-year-old patient is high. The patient has no history of breast-related surgery or trauma.

Is an ultrasound indicated in this patient for the purposes of evaluating the lesion?

If not, why do an ultrasound?

Given a spiculated mass and no history of surgery or trauma, or symptoms related to an inflammatory process, corresponding to the site of concern to the patient, a biopsy is indicated regardless of the ultrasound findings. An ultrasound is done to determine if the lesion can be imaged so that the biopsy can be done expeditiously using ultrasound guidance. Ultrasound-guided core biopsies are better tolerated by patients, particularly elderly patients, because the patient is supine as opposed to prone (with her neck turned all the way over to one side) on the dedicated stereotactic table, or sitting, if an add-on device is used. No breast compression or radiation is required when the biopsy is done using ultrasound guidance. Additionally, because orthogonal images of the needle can be obtained following firing of the needle during the biopsy, it is easier to verify that the needle has gone through the mass. This is in contrast to the unidimensional postfire images of needle positioning during a stereotactically guided biopsy.

How would you describe the ultrasound findings?

What is your leading diagnosis, and what is your recommendation?

On physical examination, a discrete, hard mass is palpated in the lower inner quadrant of the left breast. There are no findings to suggest an ongoing inflammatory process (e.g., no erythema, tenderness, or warmth over the palpable finding). An irregular, 1.5-cm hypoechoic mass with indistinct and angular margins and shadowing is imaged on ultrasound at the 8 o’clock position, 6 cm from the left nipple, corresponding to the palpable finding. The clinical, mammographic, and ultrasound findings are highly suggestive of a malignancy. Differential considerations include invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), tubular carcinoma, or invasive lobular carcinoma. Although it is uncommon, ductal carcinoma in situ can present as a mass, asymmetry density, or distortion in the absence of microcalcifications. If there were a history of trauma or surgery localized specifically to this spot, this could represent an area of fat necrosis. Rarely, in the appropriate clinical setting, this could represent an inflammatory process.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

Rather than just consider a biopsy, one is done using ultrasound guidance. An invasive ductal carcinoma (NOS) is diagnosed on the core biopsy. A 1.5-cm grade II invasive ductal carcinoma NOS is confirmed on the lumpectomy specimen. No metastatic disease is diagnosed on the sentinel lymph node [pT1c, pN0(sn) (i—), pMX; Stage I].

What are the clinical and imaging features related to invasive ductal carcinoma NOS?

Invasive ductal carcinoma NOS is the most common breast malignancy diagnosed in approximately 65% of all patients with breast

cancer. Depending on tumor size, location, and breast size, the lesion may be palpable, or skin thickening or dimpling may be noted clinically. Subareolar lesions may be associated with nipple retraction, inversion, or displacement. A spiculated mass is the most common mammographic finding in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma NOS. Associated pleomorphic calcifications, reflecting the presence of ductal carcinoma in situ, are sometimes seen in the mass or extending away from it for variable distances. If there are associated calcifications, it is important to characterize them and describe their extent.

cancer. Depending on tumor size, location, and breast size, the lesion may be palpable, or skin thickening or dimpling may be noted clinically. Subareolar lesions may be associated with nipple retraction, inversion, or displacement. A spiculated mass is the most common mammographic finding in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma NOS. Associated pleomorphic calcifications, reflecting the presence of ductal carcinoma in situ, are sometimes seen in the mass or extending away from it for variable distances. If there are associated calcifications, it is important to characterize them and describe their extent.

A round or oval mass with obscured, indistinct, or ill-defined margins is a less common mammographic presentation for invasive ductal carcinoma NOS. On ultrasound, these lesions are round or oval, solid, hypoechoic masses with well-circumscribed or partially indistinct margins; many have posterior acoustic enhancement. Some may be markedly hypoechoic. Alternatively, a complex cystic mass may be seen. When they present as a round or oval mass, invasive ductal carcinomas NOS are often rapidly growing, poorly differentiated lesions, particularly if the lesion is solid and associated with posterior acoustic enhancement on ultrasound. In lesions with cystic changes on ultrasound, necrosis is commonly present histologically.

What are the more common subtypes of invasive ductal carcinomas, and what are their clinical and imaging features?

Tubular, medullary, mucinous, and papillary carcinomas are some of the more common subtypes of invasive ductal carcinoma. Of these four subtypes, tubular carcinoma is the only one that presents as a small spiculated mass; in some patients, multiple small spiculated masses may be identified. Medullary carcinoma usually presents in premenopausal woman as a round or oval mass and is characterized by rapid growth; many of these patients present with interval cancers (within a year of a normal screening mammogram). Medullary carcinoma can be markedly hypoechoic on ultrasound (simulating a cyst). Mucinous and papillary carcinomas usually present as round or oval masses in older, postmenopausal women and are usually characterized by slower growth patterns. Ultrasound can be helpful in distinguishing among some of the mucinous and papillary carcinomas. Mucinous lesions are commonly iso- to slightly hypo- or hyperechoic and may have posterior acoustic enhancement. Papillary carcinomas, particularly those arising in the subareolar area, are often complex cystic masses with posterior acoustic enhancement.

Patient 8

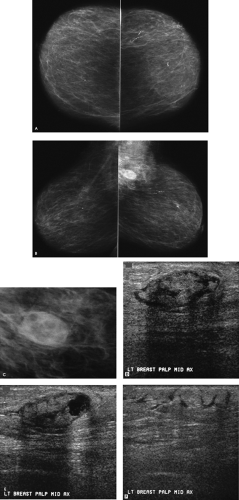

Is this a normal screening mammogram, or do you perceive a potential abnormality?

Remember to focus your attention by splitting the images into thirds. On the oblique views, focus your attention on the lower third of the breasts (Fig. 3.8C); now do you see something? Do you see a corresponding asymmetric area, medially in the right breast (Fig. 3.8D), on the craniocaudal view? What would you do next?

BI-RADS® category 0: need additional imaging evaluation. Spot compression views, correlative physical examination and an ultrasound are indicated.

What do you think now?

A 1-cm, irregular, spiculated mass is confirmed on the spot compression views. A small focus of pleomorphic calcifications is also noted in the tissue adjacent to the mass. In the absence of symptoms suggesting an ongoing infection, or a history of surgery or trauma localized to this specific area, this finding requires biopsy. Although a biopsy is indicated on the mammographic findings alone, an ultrasound is done because if the lesion is identified on ultrasound, a core biopsy can be done easily and expeditiously using ultrasound guidance.

Is this the correct location for the mammographic finding?

What is your differential?

A hypoechoic mass with irregular, spiculated, and angular margins, associated shadowing, and disruption of Cooper ligaments is imaged, corresponding to the area of mammographic concern. Although the lesion projects below the level of the nipple on the mediolateral oblique view, the lesion imaged on ultrasound corresponds to the lesion seen mammographically (Fig. 3.8I–K). Differential considerations include fat necrosis if the patient has had surgery or trauma localized specifically to this area, papilloma, sclerosing adenosis, mastitis, granular cell tumor (rare), extra-abdominal desmoid (rare), invasive ductal carcinoma not otherwise specified, tubular carcinoma, or invasive lobular carcinoma. Rarely, ductal carcinoma in situ can present as a mass, asymmetrical density, or distortion in the absence of microcalcifications. Given the imaging features of this lesion (i.e., a spiculated mass with adjacent calcifications), the working diagnosis for this patient is an invasive ductal carcinoma with associated ductal carcinoma in situ.

BI-RADS® category 4: suspicious abnormality, biopsy should be considered.

An ultrasound-guided biopsy is undertaken, and an invasive ductal carcinoma is reported on the cores. A 0.9-cm, grade I invasive ductal carcinoma with associated cribriform-type ductal carcinoma in situ is diagnosed on the lumpectomy specimen. Two excised sentinel lymph nodes are normal [pT1b, pN0(sn) (i—), pMX; Stage I].

What is the basic concept underlying sentinel lymph node biopsies?

Traditionally, most patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer had axillary lymph node dissections (ALND) for staging and as part of the surgical treatment of their breast cancer (i.e., local-regional control). More recently, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) has been suggested as an alternative to assess the status of the axilla and is being used increasingly to replace ALND for most women diagnosed with breast cancer. It is postulated that the sentinel lymph node(s) is the first node draining a tumor, and that the histologic status of this lymph node accurately predict the status of the regional (axilla) lymphatic basin.

Given some of the complications associated with ALND, sentinel lymph node biopsies are now used routinely at many institutions as an alternative to ALND for patients with clinically normal axillary exams. Axillary lymph node dissections are undertaken if the sentinel lymph node(s) is not identified, metastatic disease is known to be present following fine needle aspiration (FNA), or core biopsy, of ultrasound-detected, abnormal lymph nodes in the axilla, or when abnormal lymph nodes are suspected clinically. Axillary lymph node dissection may also be performed in patients with metastatic disease in the sentinel lymph node(s), to establish the number of axillary lymph nodes involved by tumor.

The methods used to identify the sentinel lymph node are still evolving, undergoing investigation, and vary among institutions. In general, a radioisotope is used alone or in combination with a blue dye (e.g., lymphazurin blue) for lymphatic mapping; these are injected in a peritumoral, intradermal, periareolar, or intratumoral location. The volume used and the interval between injection and surgery vary. If a radioisotope is used, preoperative lymphoscintigraphy can be used to assess the pattern of lymphatic drainage before surgery; this also provides information regarding the internal mammary lymph nodes. Alternatively, a gamma probe is used intraoperatively to identify the “hot spots” in the axillary tail without preoperative lymphoscintigraphy. It has been suggested by many researchers that optimal results are obtained when blue dye and isotope are used in combination. In a review of the literature correlating SLNB with ALND in more than 3,000 patients with breast cancer, Liberman reported technical success rate, sensitivity, and accuracy of 88%, 93%, and 97%, respectively, for SLNB.

The use of SLNB in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) remains controversial. It is probably indicated for women with DCIS and known microinvasion and for patients in whom invasive disease is suspected preoperatively based on the size or imaging features of the DCIS. The alternative approach that can be taken is to excise the DCIS and, if invasive disease is identified on the lumpectomy specimen, have the SLNB done as a second operative procedure.

What is the prognostic significance of isolated tumor cells or micrometastatic disease described following a sentinel lymph node biopsy?

The advent and now widespread use of sentinel lymph node biopsy has resulted in a more meticulous evaluation of excised lymph node(s). This includes serial sectioning of the entire lymph node (as opposed to sample sections from multiple lymph nodes) and a more focused histologic and immunohistochemical (IHC) evaluation of the excised lymph node. Some of the consequences include the observation of isolated tumor cells and micrometastatic disease. Consequently, the significance of these findings (e.g., isolated tumor cells and micrometastases) involving excised sentinel lymph nodes is not yet clear, and there is no consensus on their prognostic significance. Currently, the use of IHC evaluation of sentinel lymph nodes is not encouraged; however, it is done at many institutions. The determination of micrometastatic disease should be based on routine hematoxylin and eosin–stained histologic sections.

Patient 9

How would you describe the findings?

Scattered dystrophic and large rodlike calcifications are present bilaterally. A mixed-density (fat containing) mass is imaged on the left mediolateral oblique view, superimposed on the left pectoral muscle, corresponding to the area of clinical concern. The trabecular markings surrounding the mass are more dense and numerous compared to those in the corresponding area on the right. Given the far lateral and posterior location of the lesion, it is not imaged on the craniocaudal view and a spot tangential view could not be obtained.

What diagnostic considerations would you entertain?

Based on the mammographic findings, what BI-RADS® assessment category would you assign, and what would you do next?

The main differential considerations for a mixed-density lesion include lymph node, fibroadenolipoma (hamartoma), fat necrosis, oil cyst, galactocele, postoperative or posttraumatic fluid collection, and abscess. Although malignant lesions may rarely entrap fat, fat-containing lesions should be considered benign; consequently, no malignant lesions

are usually included in the differential for a mixed-density lesion. Prior studies in this patient are normal. Specifically, no lymph node or fibroadenolipoma is seen in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast. A galactocele is not a consideration in a 79-year-old patient. Primary considerations at this point include an abscess or a hematoma (particularly because the patient is on coumadin), both of which also help explain the associated prominence of the trabecular markings. Physical findings and additional history may be helpful in sorting through these possibilities.