Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

- ◼

The renal parenchyma can be divided into an outer region called the cortex and an inner region called the medulla.

- ◼

Parenchymal abnormalities can be divided by their involvement.

- ◼

Entire kidney (glomerulonephritides, amyloidosis, drugs, and rejection).

- ◼

Primarily cortical.

- ◼

Primarily medullary.

- ◼

- ◼

Glomerulonephritis (GN) is a complex spectrum of disorders characterized by inflammation of the glomeruli.

- ◼

It is a histological/pathological diagnosis.

- ◼

Imaging can play a role in excluding other causes of renal impairment.

- ◼

The kidneys may enlarge with acute GN, and tend to be small with chronic GN.

- ◼

Techniques

Plain radiography

- ◼

Plain radiographs play a limited role in evaluating renal pathology. Typically, calcifications projecting over the renal shadows may be identified as nephrolithiasis or in a pattern suggestive of nephrocalcinosis.

Fluoroscopy

- ◼

Intravenous urography will highlight pathologies in the renal collecting systems. The kidneys may show poor contrast excretion, depending on the stage of renal failure. Apparent expansion of the renal sinus fat (“renal lipomatosis”) can be a secondary sign of diffuse atrophy because of chronic renal disease ( Fig. 25.1 ).

Fig. 25.1

Renal sinus lipomatosis in a case with mild bilateral renal parenchymal disease. A, Intravenous pyelogram shows low-density prominent renal sinus fat. B, Computed tomography scan in the same patient confirms sinus lipomatosis.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

Ultrasonography

- ◼

The primary utility of ultrasound is to evaluate for hydronephrosis (postrenal cause of renal failure) and vascular abnormalities (inflow or outflow). In the setting of renal failure, the absence of either suggests an intrinsic renal parenchymal disease. In chronic GN, the renal parenchyma may show increased echogenicity and usually has some cortical volume loss. The normal renal echogenicity is typically equal to the adjacent liver or less than the adjacent spleen.

- ◼

Doppler ultrasonography can assist in the differential diagnosis of acute renal failure. The normal resistive index (RI) of the kidney is around 0.6 with 0.7 generally considered the upper threshold. Abnormally elevated RI can be seen in a large number of conditions, including prerenal (renal artery stenosis, renal vein thrombosis), postrenal (obstruction of urinary flow from calculi, masses, etc.), and parenchymal causes. The RI can also be normal in acute or secondary GN.

Computed tomography

- ◼

Computed tomography (CT) may show normal or bilateral renal enlargement in acute GN. Noncontrast CT may show cortical calcification in chronic GN, and typically show small kidneys with smooth contour. With chronic pyelonephritis, scarring may develop.

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

Changes in renal size and enhancement can be seen with diffuse renal disease, similar to CT.

Protocols

Protocol considerations

Computed tomography

- ◼

Noncontrast technique is useful to evaluate calcifications.

- ◼

CT urography may be helpful in evaluating the renal collecting system, and has mostly replaced the role of intravenous pyelogram (IVP).

Suggested computed tomography urography protocol

- ◼

Noncontrast CT.

- ◼

50 mL of intravenous (IV) contrast followed by an additional 50 mL 6 to 8 minutes later (“split bolus”).

- ◼

Images acquired 60 to 90 seconds following the second dose of IV contrast.

Specific disease processes

Glomerulonephritis

- ◼

Can be primary or secondary.

- ◼

Primary GN: Intrinsic to the kidney, usually immune mediated (such as poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis [PSGN]).

- ◼

Secondary GN: Associated with systemic disease, certain infections, drugs, systemic disorders (systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis), or cancers.

- ◼

- ◼

Can be acute, rapidly progressive, or chronic.

- ◼

Acute GN.

- ◼

25% to 30% of all cases of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States.

- ◼

PSGN is the most common acute cause.

- ◼

- ◼

Chronic GN.

- ◼

Accounts for 10% of patients on dialysis.

- ◼

- ◼

Imaging appearance

Ultrasound

- ◼

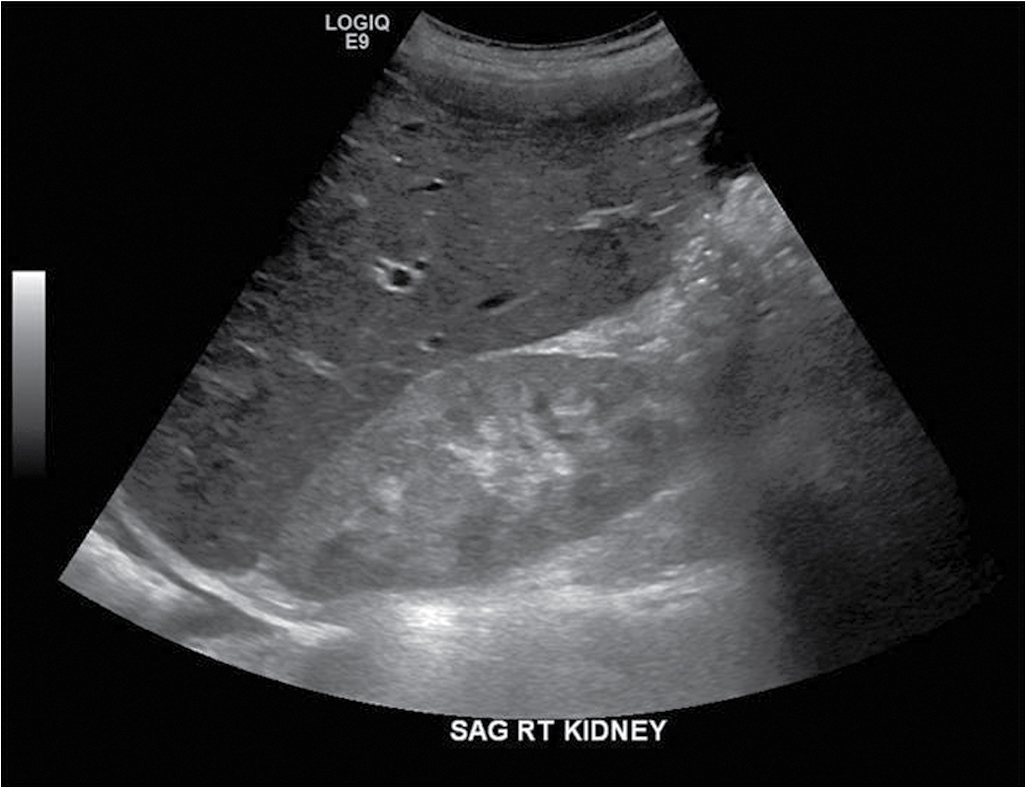

Normal or increased renal parenchymal echogenicity ( Fig. 25.2 ).

Fig. 25.2

Bilateral renal enlargement from glomerulonephritis. Images from a renal ultrasound reveal enlarged kidneys bilaterally (both kidneys >13 cm length, right kidney pictured) with increased parenchymal echogenicity compared with the adjacent index organs. The examination was performed to rule out obstruction, when elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels were discovered in a 26-year-old woman. Note the right pleural effusion. The liver and spleen were also enlarged. The patient was ultimately diagnosed with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.

(From Zagoria RJ, Brady CM, Dyer RB. Genitourinary Imaging: the Requisites , ed 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.)

Computed tomography

- ◼

Normal or bilateral renal enlargement in acute GN.

- ◼

Normal or bilateral atrophy with cortical calcifications in some cases of chronic GN ( Fig. 25.3 ).

Fig. 25.3

Axial noncontrast computed tomography through the kidneys demonstrates diffuse bilateral cortical calcification consistent with cortical nephrocalcinosis in a patient with chronic glomerulonephritis.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

Same as CT, although calcifications may be less easily identified.

Acute pyelonephritis

- ◼

Infection of the renal parenchyma and renal pelvis, inclusive of the tubules and interstitium.

- ◼

Most common cause is a gram-negative organism ( Escherichia coli , Proteus, Klebsiella, Enterobacter).

- ◼

Most cases are ascending infections from the lower urinary tract.

- ◼

Can be uncomplicated (no permanent sequelae) or complicated.

Imaging appearance

- ◼

Imaging unnecessary for uncomplicated pyelonephritis.

- ◼

Imaging used for confusing presentation or deterioration despite therapy.

- ◼

Usually multifocal, but rarely can be focal, mimicking a mass.

Ultrasound ( fig. 25.4 )

- ◼

Can be normal (negative study does not exclude pyelonephritis).

Computed tomography

- ◼

Contrast enhanced CT (CECT) is the imaging study of choice.

- ◼

“Striated nephrogram” appearance is classic ( Fig. 25.5 ).

Fig. 25.5

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study in a young woman with suspected appendicitis. An enlarged right kidney is seen with multiple wedge-shaped nonenhancing areas and perinephric stranding, findings consistent with acute pyelonephritis.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

Nuclear medicine

- ◼

Renal cortical scintigraphy technetium99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (Tc99m-DMSA) may show photopenic areas, which can represent acute infection (or scars).

- ◼

Typically used for chronic rather than acute pyelonephritis.

Chronic pyelonephritis

- ◼

Renal injury induced by recurrent or persistent renal infections.

- ◼

Progressive renal scarring may lead to ESRD.

- ◼

Associated with major anatomic abnormalities, urinary tract obstruction, renal calculi, renal dysplasia.

- ◼

Can be focal, multifocal, or diffuse; can involve one or both kidneys.

- ◼

Affected portion is typically scarred and contracted.

Imaging appearance

Computed tomography

- ◼

Cortical scarring (focal, multifocal, or diffuse) of one or both kidneys.

- ◼

If diffusely unilateral (small contracted kidney), expect compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral kidney ( Fig. 25.6 ).

Fig. 25.6

Delayed image from contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows a unilateral small scarred kidney in a case of chronic pyelonephritis. Note the polar scar and the corresponding clubbed calyx in the left kidney.

(From Sahani DV, Samir AE. Abdominal Imaging , ed 2. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree