Disorders of the Ankle and Foot

Posterior

Achilles Tendon

Achilles Tendinopathy

Achilles tendinopathy is one of the most common findings in patients with chronic heel pain. It is a common disorder with an incidence rate of 2.35 per 1000 adult patients in a large Dutch report on GP-registered patients. Most cases are encountered in the middle-aged population (age 41–60 years). It is more a degenerative (tendinosis) than an inflammatory condition, and it is caused by overuse of the tendon fibres, often related to sporting activity, including running. Sport athletes are at high risk but a relationship with sports activity is not always present.

Other factors that can play a role in the pathogenesis of tendinopathy are an imbalance between the gastrocnemius and the soleus individual contributions to the tendon, age, weight, sedentary life, vascularity, associated limb torsion and ankle abnormalities. Symptoms generally develop insidiously. It is difficult to differentiate clinically between tendinopathy and inflammation of the paratenon (paratenonopathy), all the more since the two conditions can be associated. Patients with tendinopathy present with pain, swelling, morning stiffness and impaired performance in sport activities and with daily living. Ultrasonography has a high-positive predictive value for visualization of tendinopathy, but has a lower sensitivity than MRI for detection of paratenonitis. Ultrasonography shows involvement of the hypovascularized tendon midportion (2–6 cm above the insertion), reflecting the histopathological signs of failed healing response: disruption of collagen fibres, increase in ground substance (proteoglycans), tenocyte proliferation and neovascularization. Bilateral findings are present in more than half the patients,

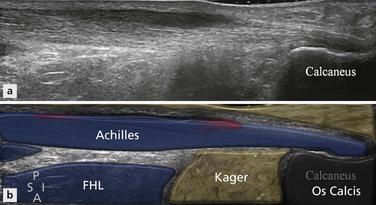

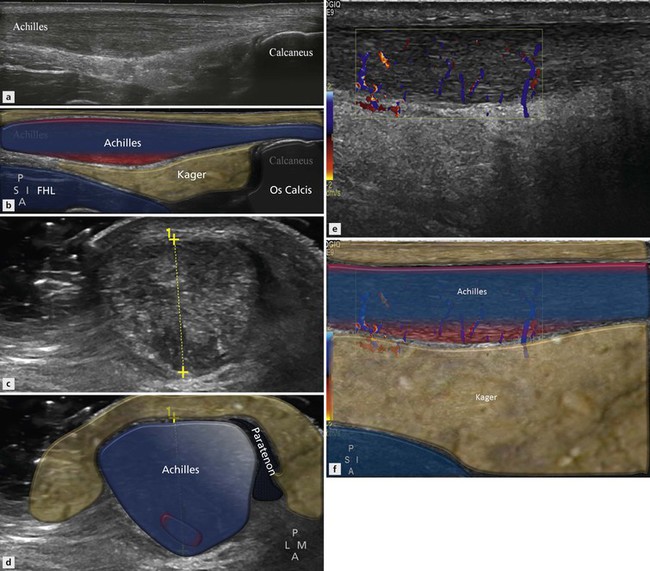

Most often the degenerative process is diffuse, leading to a painful spindle-shaped hypoechoic enlargement of the Achilles tendon (Fig. 24.1). The fibrillar structure of the tendon is nicely appreciated on longitudinal ultrasound sections, so areas of preserved and thickened fascicles can be seen (Fig. 24.2A, B). With progressive involvement, the overall echogenicity of the tendon tends to decrease, as the spacing between fibres tends to increase. It is important to avoid anisotropic artifact during this assessment. This tendon enlargement is quantified by measuring the anteroposterior diameter of the tendon: exceeding 6 mm in tendinopathy. In some patients the tendon enlargement is asymmetrical, often affecting the medial aspect of the tendon more than the lateral (Fig. 24.3). With isolated tendinopathy, there is no discontinuity of the tendon borders. On axial sections (Fig. 24.2C, D) the tendon is rounded and hypoechoic, with loss of the normal anterior flat or slightly concave contour. Colour Doppler examination often shows tendinous and/or peritendinous hyperaemia, mostly as small vessels entering the anterior border of the tendon at right angles (Fig. 24.2 E, F). This should be performed on a relaxed tendon and without too much transducer compression in order to avoid a false-negative examination due to obliteration of the vessels. Some patients may exhibit focal degenerative abnormalities, involving the anterior or posterior part of the tendon (Fig. 24.4).

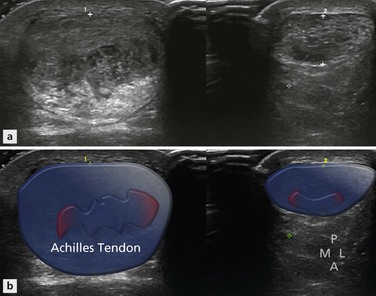

Figure 24.1 Axial images of bilateral Achilles tendinopathy. The tendon on the left is considerably more enlarged than the right, although both show areas of decreased reflectivity with focal areas of tendon delamination.

Figure 24.2 Achilles tendinopathy. (A, B) Longitudinal section showing spindle-shaped hypoechoic enlargement. (C, D) Axial section showing rounded cross section and increased anteroposterior diameter (13.2 mm). (E, F) Longitudinal colour Doppler examination showing intratendinous hyperaemia.

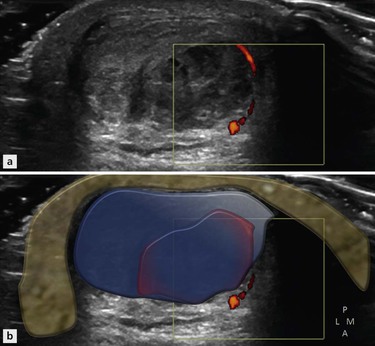

Figure 24.3 Axial image of posterior ankle. The anteromedial aspect of the tendon is more involved than the posterolateral aspect. Such a focal involvement is relatively common. There is some increased Doppler activity in the paratenon.

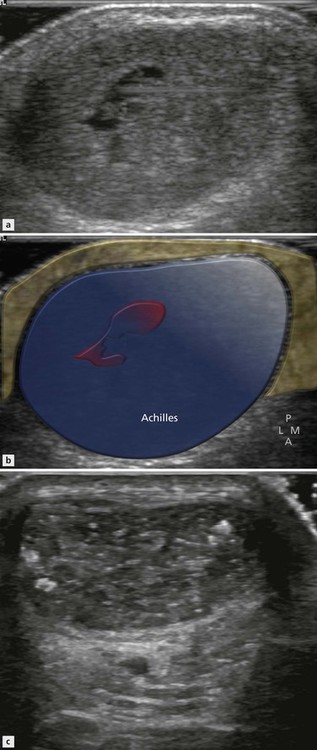

When the Achilles tendon is painful at palpation but grossly normal on ultrasound, paratenonopathy should be suspected, and subtle signs of tendinopathy (convexity of the anterior border, slight hypoechogenity or hyperaemia) and/or paratenonopathy (slight thickening of the paratenon, increased echogenicity of the pre-Achilles fat pad) should be carefully sought. Conversely, areas of tendinopathy, with or without increased colour Doppler signal, may be detected in asymptomatic tendons, though there is an increased likelihood that these tendons will eventually become symptomatic. With time, the tendon may become heterogeneous and the hypoechoic areas of degeneration may present very small anechoic, rounded or longitudinally orientated, intratendinous lesions. These are referred to as microtears or delaminations (Fig. 24.5A, B). Less commonly, calcifications may be found in the Achilles tendon (calcific tendinopathy, Fig. 24.5C). Eventually, complete or partial tear of the midportion of the tendon may occur.

Figure 24.5 Focal intratendinous changes in Achilles tendinopathy. (A, B) Small intratendinous microtear. (C) Small calcifications.

Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia is an autosomal dominant disease, characterized by elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol plasma levels, premature coronary artery disease and cholesterol deposits in extensor tendons (xanthomas) with the Achilles tendon as the most frequently affected tendon (Fig. 24.6). The presence of Achilles tendon xanthomas is pathognomonic of the disease but 25% of patients present with a normal tendon at palpation. Ultrasonography may demonstrate focal anechoic areas, confluent hypoechoic areas or an enlarged heterogeneous tendon. Ultrasonography has thus been advocated as a screening tool in clinically silent tendons in patients with hyperlipidaemia or with a family history of occurence. Achilles tendinopathy, paratenonopathy, enthesitis, retrocalcaneal bursitis and/or joint synovitis are frequent findings in rheumatic disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout or spondylarthritis. Ultrasonography can also show subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules (well-circumscribed focal hypoechoic area) in rheumatoid arthritis and intratendinous tophi in gout (heterogeneous hyperechoic areas with shadowing). Achilles tendon tears have been reported as a complication of local or systemic steroids. Severe tendinopathy can also occur as a complication of the administration of fluoroquinolone antibiotics, with a higher risk in patients with renal dysfunction. It is most frequently seen at the Achilles tendon, often bilateral and leading to tendon tear in nearly half the cases.

Achilles Paratenonopathy

Palpation is painful and thickening of the Achilles tendon is often suspected clinically. Ultrasonography may show an echo-poor thickening of the paratenon, best seen on axial scans (Fig. 24.7). The paratenon surrounds the Achilles on three sides: posterior, medial and lateral. This explains the shape of paratenonopathy: U-shaped with no enlargement anteriorly. This thickening of the paratenon is often subtle. In rare acute cases, a small amount of fluid in the paratenon can be identified. Some patients with inflammatory joint diseases exhibit a marked enlargement, often with associated tendinopathy. MRI is also sensitive for the diagnosis of paratenonitis, as diffuse soft tissue oedema around the tendon is easy to detect. In some cases, ultrasonography may show soft tissue oedema in the pre-Achilles fat pad (diffuse hyperechogenicity and heterogeneity) or the subcutaneous tissue, with careful comparison to the contralateral side. Peritendinous hyperaemia demonstrated with colour Doppler examination is also helpful for the diagnosis.

Achilles Enthesopathy

Achilles enthesopathy is caused by inflammation at the site of insertion of the tendon on the inferior part of the posterior aspect of the calcaneus. This area comprises the most distal part of the tendon, the enthesis fibrocartilage, as described by Benjamin and McGonagle, and the adjacent bone. The causes of Achilles enthesopathy are most often mechanical and related to age, overweight, sport activity, compression by hard footwear, or a short Achilles tendon, but can also be inflammatory. Inflammatory enthesitis is seen in seronegative spondylarthropathies, such as ankylosing spondylarthritis and psoriasis. Regardless of the cause, chronic enthesopathy changes can be subtle and asymptomatic.

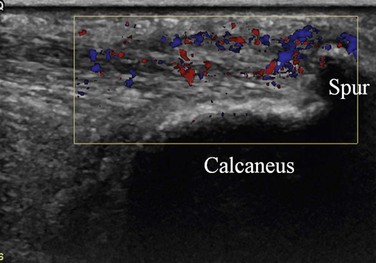

Disturbances of the interface between the tendon and the posteroinferior aspect of the calcaneus are well demonstrated on ultrasonography, sometimes better than with plain radiography or MRI. Ultrasound shows irregularity of the enthesis fibrocartilage and the underlying bone surface and posterior bone spur. On the other hand, MRI can demonstrate a focal area of bone oedema in the posteroinferior calcaneus, close to the enthesis and/or in the bone spur. Bone spur is a common asymptomatic finding.

When pain is present around a bony spur, ultrasound often confirms that focal inflammation at the spur is the cause of the pain, showing a hypoechoic area in the tendon near and proximal to the spur, containing or surrounded by local colour Doppler signal.

In addition, ultrasonography enables precise placement of the tip of the needle for local steroid injection, which can be very helpful as the subcutaneous soft tissues often are adherent to the enthesis.

In spondylarthropathies, enthesitis is predominantly encountered in the lower limbs, and especially at the Achilles tendon insertion. Achilles enthesopathy is often underestimated clinically.

Ultrasonography is especially useful to demonstrate erosions of the posterior calcaneus, but cannot visualize associated bone oedema. Local soft-tissue hyperaemia on colour Doppler may also be found and is an important feature for treatment monitoring. Adjacent bursitis, bilateral involvement and joint involvement with synovitis also occur.