Introduction

The most common symptoms leading to an ultrasound examination of the posterior ankle region are those associated with disorders of the Achilles tendon or the plantar aponeurosis (heel pain and/or swelling). In an acute setting, ultrasound is most often performed for suspicion of Achilles tendon tear. Other common acute and chronic indications are Achilles tendinopathy and/or paratenonitis, insertional Achilles tendon diseases, bursitis and plantar fasciitis. Less common indications are Sever’s disease, tear of the plantar aponeurosis, plantar fibromatosis, lesions of the plantaris tendon, an accessory soleus muscle, posterior ankle impingement and heel pad syndrome.

Achilles Tendon

Ultrasonography is the first choice imaging modality for examination of the Achilles tendon, with an unsurpassed resolution and outstanding analysis of the fibrillar tendon structure. In addition, it is the only imaging technique that enables dynamic and functional examination of the tendon. Pathological conditions that may affect the Achilles tendon have been increasing for the past decades, reflecting the increase in participation in different types of sporting activity. Diseases are most commonly divided into two groups: insertional and noninsertional. Insertional is further divided into enthesopathy (at insertion) and Haglund’s disease (proximal to insertion). In all patients, the differential diagnosis will be based on the patient’s history (pain, swelling, mechanism of disease) and the exact anatomical location of findings on ultrasound. Noninsertional findings include tendinopathy and paratenonopathy. Tendinopathy, enthesopathy and Haglund’s disease may all lead to tendon tears, so it is an important goal for ultrasonography to recognize and describe such a complication, as it might be treated surgically. Post-operatively, ultrasound may be required when tear recurrence or infection is suspected.

Achilles Tendinopathy

Achilles tendinopathy is one of the most common findings in patients with chronic heel pain. It is a common disorder with an incidence rate of 2.35 per 1000 adult patients in a large Dutch report on GP-registered patients. Most cases are encountered in the middle-aged population (age 41–60 years). It is more a degenerative (tendinosis) than an inflammatory condition, and it is caused by overuse of the tendon fibres, often related to sporting activity, including running. Sport athletes are at high risk but a relationship with sports activity is not always present.

Development of Achilles tendon degeneration has also been attributed to hind-foot valgus and hyperpronation of the foot, leading to increased stress in the medial part of the tendon.

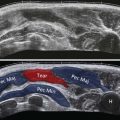

Most often the degenerative process is diffuse, leading to a painful spindle-shaped hypoechoic enlargement of the Achilles tendon ( Fig. 24.1 ). The fibrillar structure of the tendon is nicely appreciated on longitudinal ultrasound sections, so areas of preserved and thickened fascicles can be seen ( Fig. 24.2A, B ). With progressive involvement, the overall echogenicity of the tendon tends to decrease, as the spacing between fibres tends to increase. It is important to avoid anisotropic artifact during this assessment. This tendon enlargement is quantified by measuring the anteroposterior diameter of the tendon: exceeding 6 mm in tendinopathy. In some patients the tendon enlargement is asymmetrical, often affecting the medial aspect of the tendon more than the lateral ( Fig. 24.3 ). With isolated tendinopathy, there is no discontinuity of the tendon borders. On axial sections ( Fig. 24.2C, D ) the tendon is rounded and hypoechoic, with loss of the normal anterior flat or slightly concave contour. Colour Doppler examination often shows tendinous and/or peritendinous hyperaemia, mostly as small vessels entering the anterior border of the tendon at right angles ( Fig. 24.2 E, F ). This should be performed on a relaxed tendon and without too much transducer compression in order to avoid a false-negative examination due to obliteration of the vessels. Some patients may exhibit focal degenerative abnormalities, involving the anterior or posterior part of the tendon ( Fig. 24.4 ).

When the Achilles tendon is painful at palpation but grossly normal on ultrasound, paratenonopathy should be suspected, and subtle signs of tendinopathy (convexity of the anterior border, slight hypoechogenity or hyperaemia) and/or paratenonopathy (slight thickening of the paratenon, increased echogenicity of the pre-Achilles fat pad) should be carefully sought. Conversely, areas of tendinopathy, with or without increased colour Doppler signal, may be detected in asymptomatic tendons, though there is an increased likelihood that these tendons will eventually become symptomatic. With time, the tendon may become heterogeneous and the hypoechoic areas of degeneration may present very small anechoic, rounded or longitudinally orientated, intratendinous lesions. These are referred to as microtears or delaminations ( Fig. 24.5A, B ). Less commonly, calcifications may be found in the Achilles tendon (calcific tendinopathy, Fig. 24.5C ). Eventually, complete or partial tear of the midportion of the tendon may occur.

Treatment of tendinopathy is essentially conservative with a period of rest, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication and heel lift, followed by physiotherapy (eccentric training), and sometimes surgery in resistant situations. Some rare forms of tendinopathy are related to a specific cause and have to be treated accordingly: lipid-storage disorders, rheumatic diseases, treatment by local or systemic steroids, or certain antibiotics.

Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia is an autosomal dominant disease, characterized by elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol plasma levels, premature coronary artery disease and cholesterol deposits in extensor tendons (xanthomas) with the Achilles tendon as the most frequently affected tendon ( Fig. 24.6 ). The presence of Achilles tendon xanthomas is pathognomonic of the disease but 25% of patients present with a normal tendon at palpation. Ultrasonography may demonstrate focal anechoic areas, confluent hypoechoic areas or an enlarged heterogeneous tendon. Ultrasonography has thus been advocated as a screening tool in clinically silent tendons in patients with hyperlipidaemia or with a family history of occurence. Achilles tendinopathy, paratenonopathy, enthesitis, retrocalcaneal bursitis and/or joint synovitis are frequent findings in rheumatic disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, gout or spondylarthritis. Ultrasonography can also show subcutaneous rheumatoid nodules (well-circumscribed focal hypoechoic area) in rheumatoid arthritis and intratendinous tophi in gout (heterogeneous hyperechoic areas with shadowing). Achilles tendon tears have been reported as a complication of local or systemic steroids. Severe tendinopathy can also occur as a complication of the administration of fluoroquinolone antibiotics, with a higher risk in patients with renal dysfunction. It is most frequently seen at the Achilles tendon, often bilateral and leading to tendon tear in nearly half the cases.

Achilles Paratenonopathy

Paratenonitis means inflammation of the paratenon. The most common cause is mechanical and secondary to an overuse injury, either isolated (initial stage) or associated to tendinopathy (late stage). Paratenonosis fibrous adhesions can develop in chronic situations (paratendinosis), limiting tendon movement. Other causes of paratenonitis are rheumatic diseases and especially spondylarthropathies.

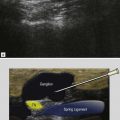

Palpation is painful and thickening of the Achilles tendon is often suspected clinically. Ultrasonography may show an echo-poor thickening of the paratenon, best seen on axial scans ( Fig. 24.7 ). The paratenon surrounds the Achilles on three sides: posterior, medial and lateral. This explains the shape of paratenonopathy: U-shaped with no enlargement anteriorly. This thickening of the paratenon is often subtle. In rare acute cases, a small amount of fluid in the paratenon can be identified. Some patients with inflammatory joint diseases exhibit a marked enlargement, often with associated tendinopathy. MRI is also sensitive for the diagnosis of paratenonitis, as diffuse soft tissue oedema around the tendon is easy to detect. In some cases, ultrasonography may show soft tissue oedema in the pre-Achilles fat pad (diffuse hyperechogenicity and heterogeneity) or the subcutaneous tissue, with careful comparison to the contralateral side. Peritendinous hyperaemia demonstrated with colour Doppler examination is also helpful for the diagnosis.

Achilles Enthesopathy

Achilles enthesopathy is caused by inflammation at the site of insertion of the tendon on the inferior part of the posterior aspect of the calcaneus. This area comprises the most distal part of the tendon, the enthesis fibrocartilage, as described by Benjamin and McGonagle, and the adjacent bone. The causes of Achilles enthesopathy are most often mechanical and related to age, overweight, sport activity, compression by hard footwear, or a short Achilles tendon, but can also be inflammatory. Inflammatory enthesitis is seen in seronegative spondylarthropathies, such as ankylosing spondylarthritis and psoriasis. Regardless of the cause, chronic enthesopathy changes can be subtle and asymptomatic.

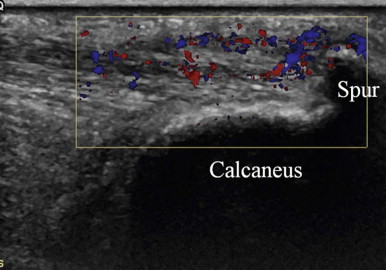

The typical ultrasound findings of enthesopathy are enlargement of the tendon insertion, which becomes hypoechoic, sometimes with calcifications or spur, and often hypervascularized on colour Doppler examination ( Fig. 24.8 ).

| When pain is present around a bony spur, ultrasound often confirms that focal inflammation at the spur is the cause of the pain, showing a hypoechoic area in the tendon near and proximal to the spur, containing or surrounded by local colour Doppler signal. |

Signs of enthesitis can be present in different rheumatic diseases but are a characteristic pathological feature of spondylarthropathies.

Ultrasonography has been shown to detect subclinical enthesitis and is increasingly performed as it has the potential to improve the diagnosis of spondylarthropathy and the monitoring of its treatment.

The main differential diagnoses are Haglund’s disease, calcaneal stress fracture, heel pad syndrome, and plantar fasciitis. Calcaneal tumours are rare but calcaneal stress fracture is not and may be seen in runners. Plain radiography is normal with stress fractures, and the diagnosis is usually made using MRI, which shows focal bone oedema around a fracture line. Ultrasound is positive only if the cortex is involved. Isotope bone-scan has been advocated but carries a high radiation dose. CT is used to assess healing.

Haglund’s Disease

Haglund’s disease is a mechanical disorder causing heel pain, first described in 1928, and classically based on the Haglund’s triad: hypertrophy of the posterosuperior portion of the calcaneal tuberosity (Haglund’s deformity), retrocalcaneal bursitis and focal changes in the anterior distal Achilles tendon. These pathological findings are located in the proximal, preinsertional part of the enthesis, and not at the level of the tendon insertion. On clinical examination, pain and swelling are found in the angle between the calcaneal tuberosity and the Achilles tendon. It is believed to be related to impingement of the tendon on the hypertrophied tuberosity during dorsal flexion of the ankle, often related to sport activity in young subjects (running, soccer, racket sports and gymnastics). The use of rigid shoes has also been incriminated in the pathogenesis.

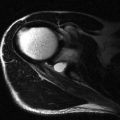

On ultrasonography the diagnosis is based on the soft tissue changes ( Fig. 24.9A, B ): retrocalcaneal bursitis and a focal hypoechoic area in the anterior part of the distal Achilles tendon, corresponding to the sesamoid fibrocartilage described by Benjamin and McGonagle. Bone irregularities can be detected on the surface of the calcaneal tuberosity (corresponding to the periosteal fibrocartilage), but plain radiography is needed to demonstrate the hypertrophy of the tuberosity. Different radiological measurement techniques have been developed to quantify this hypertrophy. MRI has the ability to show all the elements of the diagnostic triad, but also areas of focal oedema in the posterosuperior calcaneus and/or the pre-Achilles fat pad ( Fig. 24.9C ).