Disorders of the Elbow

Lateral

Lateral Elbow

Common Extensor Origin Epicondylalgia

Thompson’s manoeuvre: resisted wrist dorsiflexion with the elbow extended and the forearm pronated results in pain, which radiates down the forearm.

Pathologically there is angiofibroplastic hyperplasia and mucoid degeneration of the CEO. The extensor carpi radialis brevis component shows the earliest involvement.

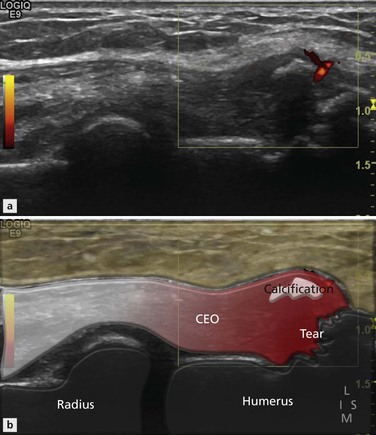

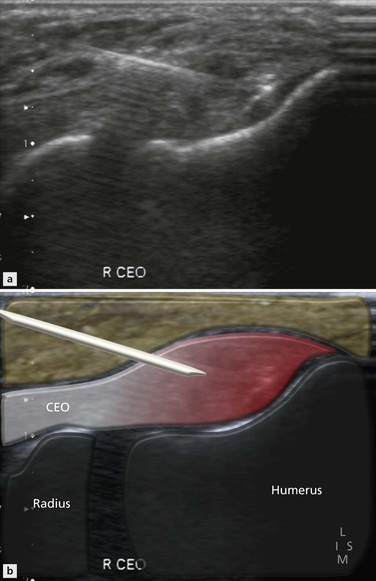

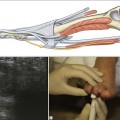

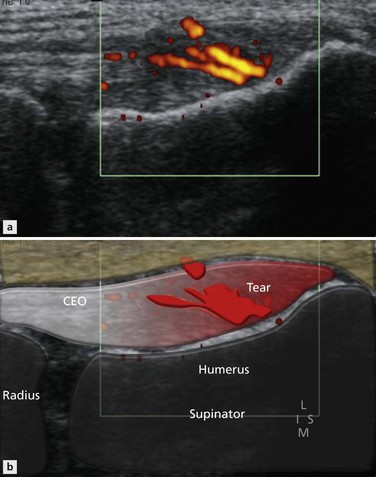

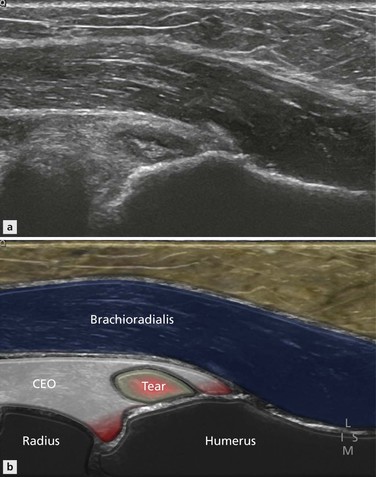

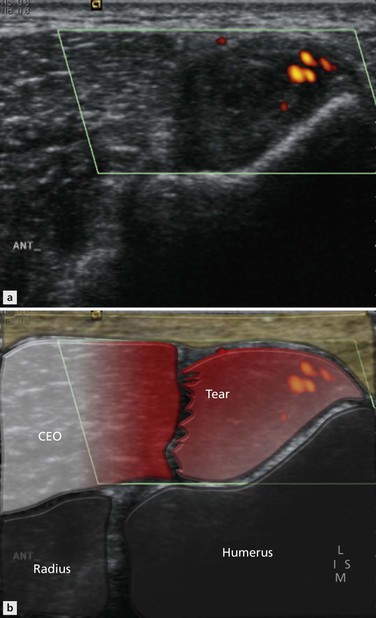

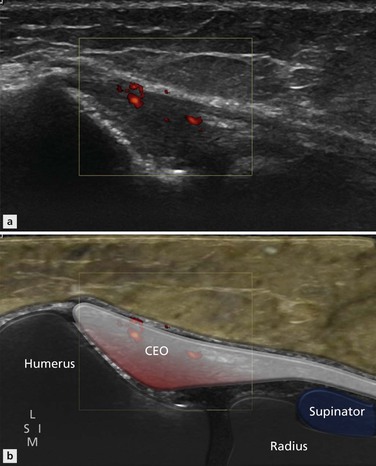

The ultrasound anatomy and examination techniques have been described previously. The characteristic findings in patients with CEO tendinopathy include loss of reflectivity and disorganization of the normal reticular fibre pattern within the involved tendons. The anterior part is affected more often than the posterior, and the deeper portions more than the most superficial. This pattern reflects the characteristic involvement of extensor carpi radialis brevis. As the disease progresses, ingrowth of abnormal vessels (neovascularization or angiogenesis) occurs and abnormal Doppler signal is commonly found (Fig. 6.1). The degree of vascular ingrowth is so great in some patients, that it has been suggested that much of the high signal within the tendons identified on fat-suppressed T2-weighted MR images represents abnormal vessels. As tendon degeneration progresses, fibre disruption appears and areas of focal tendon delamination or partial tears are seen (Fig. 6.2). The disease progresses to involve the adjacent tendons. Involvement of the radial collateral ligament may also occur and this is said to carry a poor prognosis for conservative management. With further progression, the tendon may begin to separate from its periosteal attachment (Fig. 6.3) and ultimately rupture occurs. There appears to be a good correlation between active Doppler changes and areas of tendon delamination with patient symptoms (Fig. 6.4).

Figure 6.1 Coronal image of lateral elbow. Increased Doppler activity is a useful marker of epicondylitis. Note also the loss of reflectivity.

Figure 6.2 Coronal image of lateral elbow. There is a split in the common extensor origin at the humeral attachment.

Figure 6.3 Coronal image of lateral elbow. Extensive delamination with partial separation of the common extensor origin from its humeral attachment. This represents a relatively late and advanced stage of the disease.

Figure 6.4 Coronal image of lateral elbow. There is loss of the normal reflectivity with increased Doppler activity in the common extensor origin consistent with epicondylitis.

Enthesopathy is the term used to describe pathological changes at the enthesis, the point where the tendon inserts into the lateral epicondyle. Occasionally this is distinct from tendinopathy but in practice the two coexist and often merge. Chronic enthesopathy is diagnosed when insertional bone changes are present at the tendon attachment. Such findings include calcification, which can assume several patterns: linear or conglomerates. With maturity the calcium deposits may ossify. Bony irregularity of the attachment site (Fig. 6.5) leads to spur formation, visible on radiographs. It should be noted that bony changes at the enthesis may persist and become chronic and are, therefore, not necessarily associated with active symptoms. Active Doppler at the enthesis is a more helpful sign of an active problem.

The ultrasound report of patients with CEO enthesopathy should confirm the diagnosis, indicate which tendons are involved and attempt to differentiate between simple tendinopathy and delamination/partial tears. Doppler activity and radial collateral ligament involvement help to stage the disease.

Although in most cases the disease is due to disordered biomechanics (as outlined above), some cases may be secondary to systemic disease, drug therapy and crystal deposition, especially gout. Once the diagnosis is established, treatment revolves around identifying and managing the underlying cause. When pain is persistent, ultrasound can be used to guide dry needle therapy and autologous blood or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection (Fig. 6.6). This is covered in more detail in the intervention chapter.

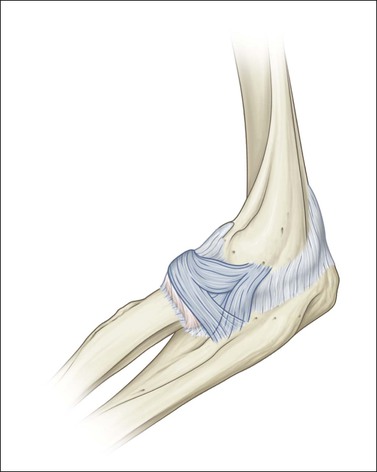

Radial Collateral Ligament and Plica

The radial collateral ligament runs from the lateral epicondyle deep to the CEO proximally, to the lateral aspect of the neck of the radius distally, where it inserts on the annular ligament (Fig. 6.7). Apart from being simultaneously involved in patients with CEO tendinopathy and traumatic injury, there are relatively few disorders that affect the ligament in isolation and it is relatively uncommon that imaging is required. The radial collateral ligament is not as easy to identify as the ulnar collateral ligament but it can be found on the deep aspect of the common CEO.