Disorders of the Groin and Hip

Anterior

Intraarticular Hip Pathology

Joint Effusion

The probe is placed in an oblique longitudinal plane along the line of the femoral neck. Joint fluid is identified deep to the echogenic joint capsule, and may appear from hypoechoic to anechoic depending on the nature of the fluid (Fig. 18.1). In adults, a bone to capsule distance of 7 mm and an asymmetrical distension of the anterior recess of more than 2 mm compared to opposite side is diagnostic of joint effusion. However, Ultrasound is nonspecific, and it may be difficult to differentiate simple fluid, septic arthritis and synovial thickening.

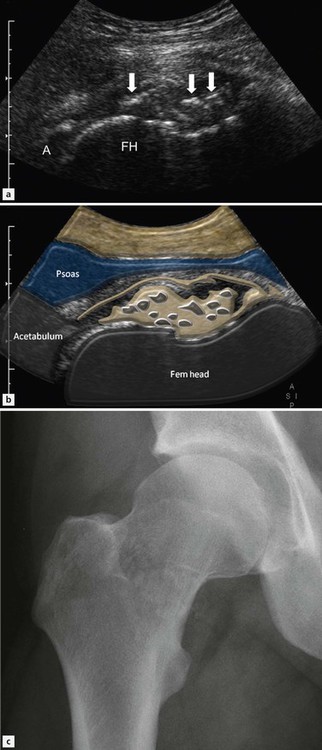

Figure 18.1 Ultrasound image along the long axis of the femoral neck shows anechoic fluid in the left hip joint elevating the joint capsule (arrows). The appearances are consistent with a simple joint effusion.

Internal echoes may be seen within an exudative effusion, and there may be associated thickening of the joint capsule. However, the absence of internal echoes does not exclude infection, and ultrasound-guided aspiration is indicated to avoid delay in diagnosis. Ultrasound-guided hip aspiration or injection in adults is performed in the transverse plane with the probe over the femoral head or neck and a 22 G spinal needle introduced from a lateral approach. This enables the operator to keep the needle parallel to the probe face for optimal visualization.

Proliferative Synovial Disorders

Synovial osteochondromatosis is a neoplastic condition of the synovial membrane. It presents with joint pain, recurrent swelling and intermittent locking. In the early stage of disease, there is hypertrophy of the synovium, with formation of chondral bodies that are released in the joint. In the final stage these bodies may calcify or even ossify. A thickened echogenic synovium may be demonstrated on ultrasound in the early stages, with areas of low echogenicity that represent chondral nodules that may not be visible on radiography. After mineralization, these nodules become echogenic and produce distal acoustic shadowing (Fig. 18.2).

Figure 18.2 Ultrasound images (A, B) along the long axis of the femoral neck demonstrating multiple echogenic foci (white arrows), consistent with small intraarticular bodies secondary to synovial osteochondromatosis. The radiograph (C) shows subtle calcified loose bodies projected over the femoral neck, confirming the diagnosis.

Acetabular Labrum

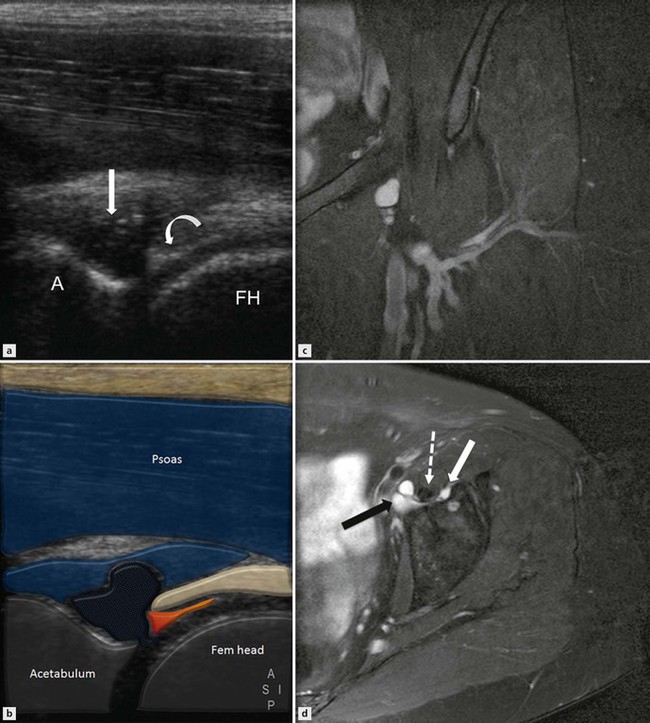

Labral tears are more apparent in the presence of paralabral cysts, which are analogous to meniscal cysts in the knee. Paralabral cysts are hypoechoic lobulated lesions and may have internal septations (Fig. 18.3). They are generally noncompressible. Most cysts are small in size compared to the iliopsoas bursa and may have a thick wall. Uncommonly, large cysts may extend deep to the iliopsoas muscles and compress the femoral neurovascular bundle. These can rarely present as a groin mass.

Figure 18.3 Ultrasound images (A, B) of the hip joint. A paralabral cyst (white arrow) is seen arising through a tear of the labrum (curved white arrow). The corresponding axial T2FS MR images (C, D) show the cyst arising from the joint margin (white arrow) extending deep to the iliopsoas tendon (broken white arrow), with a larger portion of the cyst (black arrow) lying between the iliopsoas tendon and the femoral vessels.

Extraarticular Hip Pathology

Muscle and Tendon Disorders

Iliopsoas Tendon

Snapping Hip

Snapping hip syndrome is a condition in which there is an audible or perceptible click during the hip movement, and may or may not be associated with pain. Snapping hip may be due to intra- or extraarticular causes. Intraarticular snapping hip is due to labral tears or intraarticular loose bodies. Extraarticular tendon snapping is divided into medial and lateral types. The lateral type is due to iliotibial band or gluteus maximus snapping over the greater trochanter, and is discussed in Chapter 19.

The medial type is due to abnormal movement of the iliopsoas tendon. It is now recognized that the snapping occurs more commonly due to abnormal rotation of the psoas tendon around the iliacus rather than snapping over the iliopectineal eminence.

Dynamic ultrasound is performed in an oblique transverse plane along the line of the superior pubic ramus, with the patient in a supine position.

Often the patient can voluntarily perform the specific manoeuvre that can produce the snapping sensation.

Alternatively, it is possible to dynamically assess the tendon as the hip is moved from a flexed, abducted and externally rotated position (frog lateral) to neutral.

A sudden and rapid lateral to medial, or rotatory, movement of the tendon may be combined with abrupt contact of the tendon against the pubic bone. This movement may be quite subtle. The finding on ultrasound should be correlated with the snapping sensation and pain. Associated iliopsoas tendinopathy and bursitis is encountered variably.

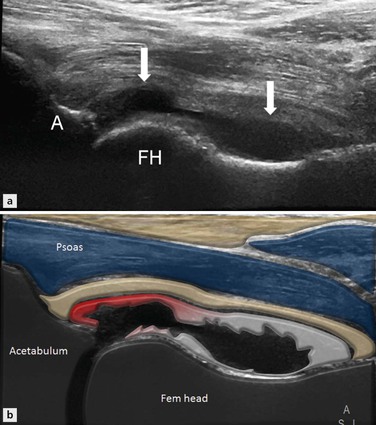

Iliopsoas Bursa

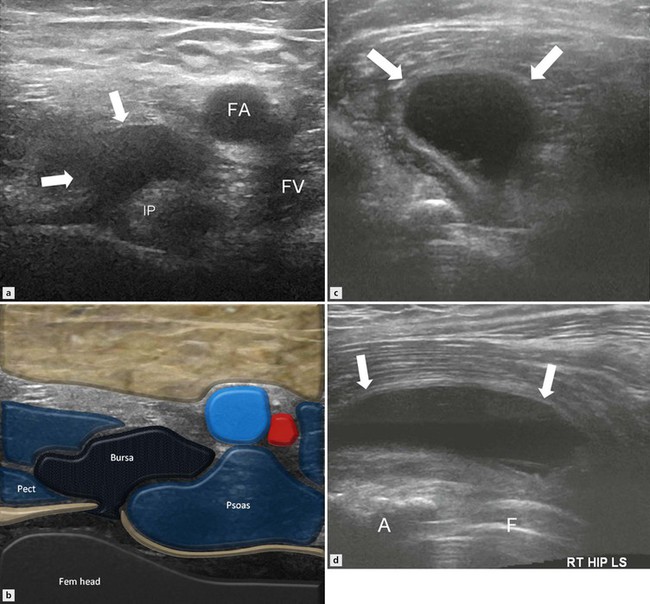

Iliopsoas bursitis usually presents as hip and groin pain, which may be exacerbated by hip flexion. Rarely a very distended bursa may present as a nonspecific mass in the groin. The bursa is situated deep to the musculotendinous junction of the psoas muscle, and communicates with the hip joint in 15% of patients. It is only visualized on imaging when it is distended with fluid (Fig. 18.4). A fluid-filled bursa appears as a thin-walled cystic structure located between the femoral neurovascular bundle medially and the iliopsoas tendon laterally. Bursal distension can rarely produce compression neuropathy of the femoral nerve. Large bursae may also extend into the pelvis along the iliacus muscle and may displace the pelvis structures.

Figure 18.4 Transverse ultrasound images demonstrating an iliopsoas bursa in the right groin (A, B). There is an anechoic fluid collection (arrows) around the iliopsoas tendon. Transverse and longitudinal images (C, D) in different patients with a total hip replacement show a much larger iliopsoas bursa (arrows).