Disorders of the Groin and Hip

Lateral and Posterior

Greater Trochanter Pain Syndrome

Abductor tendon abnormalities are a common cause of the so-called greater trochanter pain syndrome:

In obese patients it may be necessary to use probe pressure or decrease probe frequency to adequately visualize the tendon insertion.

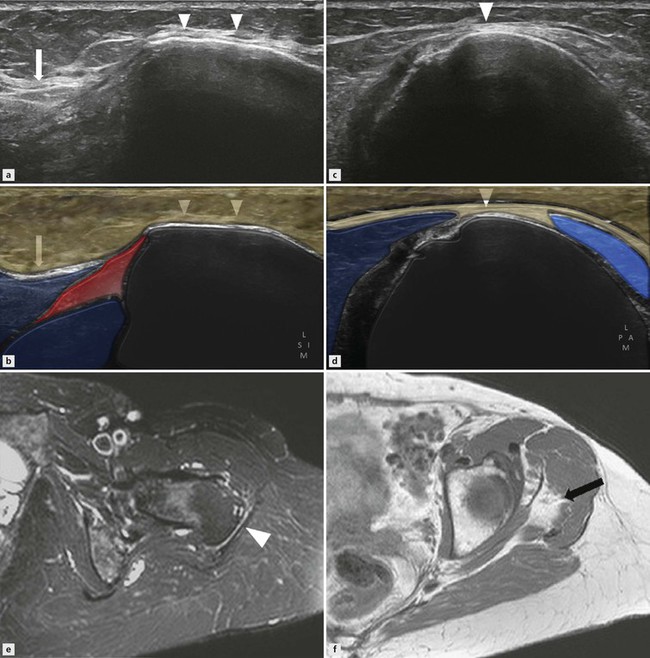

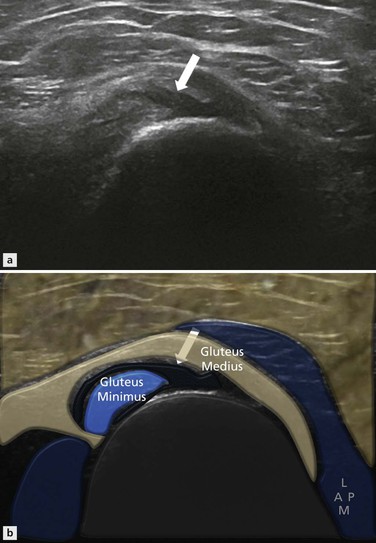

Tendon thickening and diffuse hypoechogenicity are the hallmarks of gluteal tendinopathy. The anterior fibres of gluteus medius are most commonly involved (Fig. 19.1), and may extend into the gluteus minimus tendon. Isolated involvement of gluteus minimus is not common. Subgluteus minimus and medius bursitis may coexist, seen as fluid-filled structures deep to the associated tendon with gluteal tendinopathy (Fig. 19.2). Bony irregularity of the greater trochanter due to entheseal bone formation is frequently encountered but does not correlate with disease severity. Increased tendon vascularity on Doppler imaging representing neovascularization is less common than in other tendon groups. End stage tendinopathy may result in abductor tendon tears.

Figure 19.1 Gluteus medius tendinosis. A longitudinal ultrasound image at the level of the greater trochanter shows thickening and low echogenicity of gluteus medius tendon (arrows).

Figure 19.2 Subgluteus medius bursitis. An anechoic fluid collection is present deep to the gluteus medius tendon at the level of the greater trochanter on a transverse ultrasound image.

In an acute full-thickness tear the tendon is retracted with haematoma and effusion adjacent to the greater trochanter. In chronic complete tears, muscle wasting may be evident with loss of muscle bulk and increased echogenicity due to fatty replacement. Ultrasound diagnosis of partial and complete gluteal tendon tears has a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 95% compared against surgery as a gold standard.

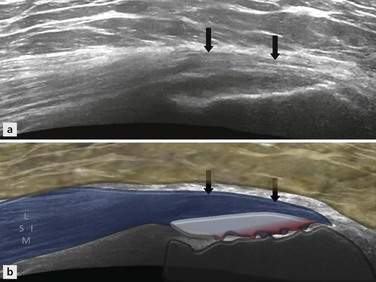

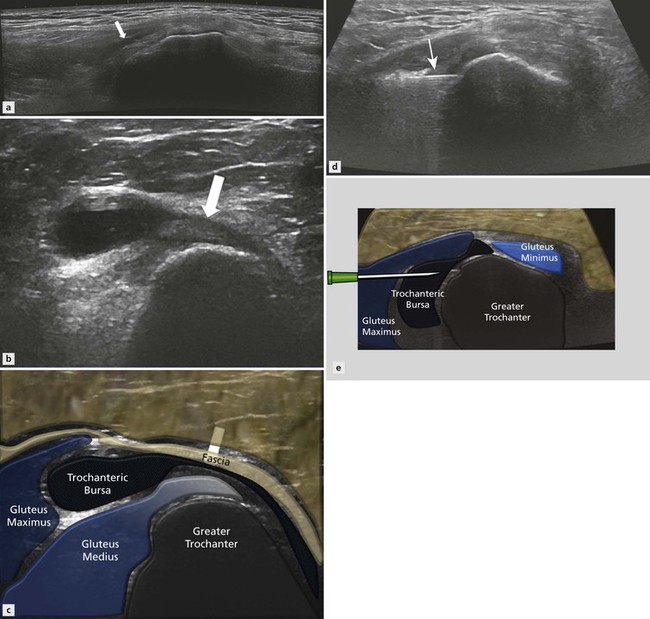

The trochanteric bursa, or subgluteus maximus bursa, is a crescenteric low-echo structure that lies lateral and superficial to the gluteus medius insertion, adjacent to the posterior facet of greater trochanter, and deep to the gluteus maximus muscle. Trochanteric bursitis is thought to be the result of an impingement phenomenon and may be present in up to 40% of patients with gluteus medius and minimus tendinopathy (Fig. 19.4). If the hip abductors are weakened by tendinopathy, lateral subluxation of femoral head occurs, leading to impingement of the soft tissues between the greater trochanter and the iliotibial tract and development of bursitis. Therefore, trochanteric bursitis may be a sequela of hip joint instability, and hence the association with tendinopathy. Bursitis is commonest in the fifth and sixth decades but may be encountered in other age groups. Other less common causes of trochanteric bursitis are rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis and other systemic inflammatory conditions.

Figure 19.4 Trochanteric bursitis. The longitudinal ultrasound image scan (A) shows a fluid collection (arrow) superficial to the gluteus medius tendon and deep to the gluteus maximus. A transverse image (B, C) (in a different patient) at the greater trochanter shows a distended trochanteric bursa superficial and posterior to the gluteus medius tendon. An ultrasound-guided injection has been performed (D, E) with a needle placed in the trochanteric bursa (arrow).

Calcification in the gluteal tendons has been reported in 10–40% of cases of gluteal tendinopathy. This can be linear or in the form of multiple small foci near the tendon insertion, and is often a result of degenerative tendinopathy. However, larger deposits of calcific tendinopathy may occur in hydroxyapatite deposition disease. The calcification appears as areas of increased echogenicity, which may or may not cast an acoustic shadow dependent on size and status of the calcification (Fig. 19.5). Spontaneous resorption of the calcific deposits may occur. Calcific tendinosis may be associated with trochanteric bursitis.