Disorders of the Groin and Hip

Paediatric Hip

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Role of Ultrasound

Plain radiographs are poor at assessing acetabular dysplasia and hip subluxation. Some measurements, notably the acetabular angle, when combined with careful radiographic technique have some value, but difficulties with image reproduction and interobserver variation are still a problem. CT and MRI can be effective but the radiation or financial cost of these investigations precludes their use as a screening tool, especially in infants. Ultrasound is ideally placed to assess the infant hip as it can visualize the unossified components of the acetabulum and femoral head, is dynamic enough to assess subluxation and does not carry a radiation risk.

Acquiring a Standard Image

The child is placed in a foam-filled trough to provide support and prevent excessive movement.

To examine the child’s right hip, the examiner’s right hand secures the infant’s knee with the hip and knee in a gently flexed position (Fig. 20.1). The fingers of the right hand are placed along the inside of the child’s thigh. The probe is held in the left hand and is gently placed on the lateral aspect of the hip in a long-axis coronal position. No pressure is used, and it is better to allow the child to move as they want to and to concentrate on acquiring the correct image when they choose to relax. This prevents unnecessary distress. With practice, a satisfactory image can be achieved quite quickly within the windows of opportunity. A foot pedal to freeze the frame and a rewind facility are helpful for particularly active bubskis!

Figure 20.1 DDH examination. The infant is placed in a foam trough in a decubitus position. This is comfortable for the infant and reduces unnecessary movement.

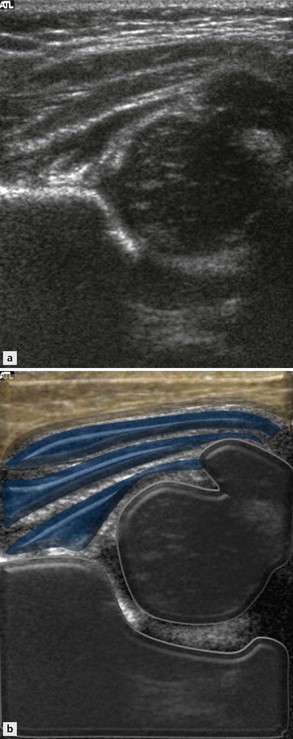

The key components of the image are the unossified femoral head and acetabulum (Fig. 20.2). The ideal image should demonstrate the acetabulum at its maximal depth through the triradiate cartilage without excessive probe tilt. The reflective lateral wall of the ilium should be a straight line, parallel to the probe. A line drawn along this is called the base line. A sharp margin between the base line and the bony roof of the acetabulum should be present as the roof line turns downwards. Between the roof line and the femoral head lies unossified roof acetabular cartilage onto which the reflective fibrocartilaginous labrum attaches. Most of the femoral head is unossified. An ossified nucleus at various stages of development may be seen within it. Unossified femoral head cartilage has a typical speckled appearance. The speckles represent vessels and in some cases Doppler activity can be detected within them. The overlying hyaline cartilage representing articular cartilage has a smoother low-reflective appearance.

Graf Angles vs Coverage Measurements

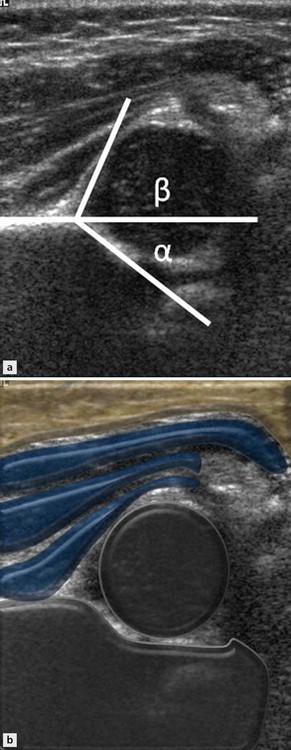

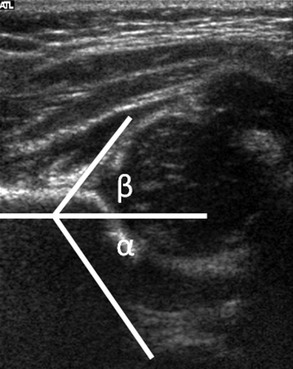

Graf is an orthopaedic surgeon who pioneered much of the early work in ultrasound assessment of the dysplastic hip. He describes two angles, α and β, which help define acetabular depth and femoral head coverage. The α angle is the angle between the base line and the acetabular ‘roof’ line (Fig. 20.3). The β angle is the angle between the base line and a line drawn from the tip of the acetabular rim (junction of the base line and roof line) through the tip of the acetabular labrum. The two angles are used to classify the infant hip into specific types and this classification is used to determine management. The higher the α angle, the deeper the acetabulum.

Figure 20.3 Standard hip ultrasound examination. The iliac line is horizontal to the probe and the acetabular roof line clearly visible. Note the speckled reflectivity of unossified hyaline cartilage in the femoral head and greater trochanter. The α angle is calculated between the iliac baseline and the acetabular roof line. The β angle is calculated between the iliac baseline and the line joining the acetabular rim and the tip of acetabular labrum.

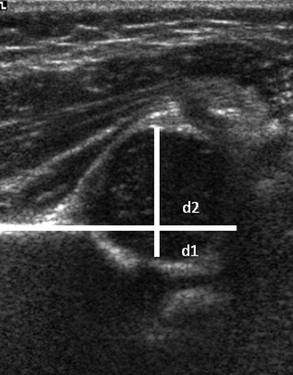

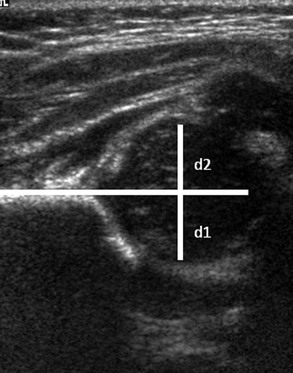

An alternative method of assessing acetabular depth is to determine what proportion of the femoral head is contained within the acetabulum. If a line drawn along the base line is continued, it normally passes through the femoral head. The proportion of the femoral head diameter that lies below this line is measured (Fig. 20.4) and the normal value is > 40%.

Figure 20.4 The proportion of femoral head contained deep to the iliac baseline can be calculated as a proportion of the femoral head diameter (d1/(d1+d2)).

It will be noted from these two measurements that there is a relationship between the Graf α angle and femoral head coverage and both are used separately and together in different centres. The bigger the α angle, the steeper is the acetabular roof and the more femoral head will be contained by it. Conversely, a shallow hip has a lower α angle (Fig. 20.5) and less of the femoral head is covered by acetabulum (Fig. 20.6).

Correlation between the α angle and femoral head cover is lost in babies with very immature hips where there is a large unossified cartilage anlage. In these infants the α angle will be low, suggesting a shallow acetabulum, but femoral head coverage may be normal. This is because much of the femoral head will be covered by unossified cartilage, but covered nonetheless. The α angle is low because it is measured from the bony and not cartilage acetabular roof. This situation needs to be viewed with some caution as there may be a greater deforming pressure on the cartilage anlage than usual. Once this immature cartilage ossifies, the α angle becomes normal.

Dynamic Examination

Whatever method is used to assess acetabular morphology, the examination is incomplete without some evaluation of the dynamic stability of the joint. In the standard decubitus examination position of a right hip, the fingers of the operator’s right hand are extended along the inside of the infant’s thigh. Gentle abduction pressure can be applied by the examiners fingers and the relative position of the femoral head to the acetabulum noted during this manoeuvre. It is important not to apply counterpressure with the probe as this may prevent subluxation. Movement is best appreciated by observing the deep aspect of the femoral head and its relationship to the tri-radiate cartilage (Fig. 20.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree