Neural Entrapment

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

The carpal tunnel is formed posteriorly by the carpal bones and extrinsic ligaments, and anteriorly by the flexor retinaculum or transverse carpal ligament, a thin fibrous band which inserts into the scaphoid and trapezium on the radial aspect and into the pisiform and hook of hamate on the ulnar side. The flexor retinaculum can normally be identified as a thin, 1–1.5 mm, slightly convex, hypoechoic band, which extends over the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), flexor pollicis longus (FPL) tendons and the median nerve in the carpal tunnel. The median nerve usually runs superficial to the FDS tendon for the second finger and medial to the FPL tendon.

Any condition leading to increased pressure within the carpal tunnel can lead to compression of the median nerve.

Aetiological factors of carpal tunnel syndrome include anatomical variants (congenitally narrow tunnel, fracture malalignment of the carpal bones, persistent median artery and accessory muscles), systemic and endocrine disorders (diabetes, pregnancy, hypothyroidism and amyloidosis) and space occupying lesions within the tunnel.

Patients with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) typically complain of burning pain, numbness and paraesthesia over the radial aspect of the hand, first three fingers and radial half of the ring finger. Symptoms typically occur at night and are exacerbated by prolonged manual work. In long-standing cases, there may be permanent motor and sensory deficit in the median nerve territory with atrophy of the thenar eminence.

In early CTS, morphological abnormalities of the median nerve do not occur and there may be no detectable abnormality on ultrasound.

| A normal nerve does not exclude the diagnosis of CTS. |

With time, the nerve becomes oedematous with evidence of progressive demyelination and fibrosclerosis at histology. When abnormalities are present, the ultrasound findings of CTS can be divided into changes of the median nerve, the flexor retinaculum and the content of the carpal tunnel.

Median Nerve Changes

Size

The median nerve is typically swollen at the proximal carpal tunnel and flattened as it passes beneath the flexor retinaculum and at the distal extent of the tunnel ( Fig. 13.1 ), regardless of the cause of compression. An abrupt change in the calibre of the nerve at the proximal carpal tunnel is referred to as the ‘notch sign’ ( Fig. 13.2 ).

| The cross sectional area of the median nerve should be measured at the point of maximum enlargement. This usually occurs just proximal to the flexor retinaculum, a position located slightly cranial to the pisiform. |

| The transducer should always be perpendicular to the nerve, including when the nerve courses obliquely from superficial to deep. |

There is no consensus in the literature regarding the most appropriate median nerve size for establishing the diagnosis of CTS.

An increased cross sectional area of more than 10 mm 2 at the proximal carpal tunnel (scaphoid–pisiform level) is generally accepted to be diagnostic of CTS.

| Comparing cross sectional area measurements of the median nerve at the level of the carpal tunnel and pronator quadratus has been proposed to eliminate interindividual and internerve variability. A difference in the cross sectional area of 2 mm 2 or greater yielded the greatest sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of CTS. |

Occasionally, the notch sign may occur at the distal edge of the retinaculum (inverted notch sign). In these cases, the nerve is flattened at the distal tunnel and no shape change is seen at the proximal tunnel. An inverted notch sign indicates distal compression, which should be highlighted in the report so that appropriate distal or palmar electrophysiological testing is performed.

Distal flattening of the nerve is evaluated with the flattening ratio, which is calculated at the distal tunnel (hamate level) by dividing the transverse diameter of the nerve by its anteroposterior diameter. A flattening ratio of more than 3 has been proposed as an additional finding of CTS.

Appearance

| The median nerve becomes uniformly hypoechoic with loss of the normal fascicular pattern (in CTS) due to overcrowding of oedematous nerve fascicles or fibrosis in chronic cases ( Fig. 13.2 ). |

There is usually increased blood flow in the longitudinal perineural plexus and intraneural vessels with Doppler imaging. This is due to disturbances in the intraneural microvasculature and hyperaemia of inflammatory neuritis.

Restricted motion of the compressed median nerve beneath the flexor retinaculum during flexion and extension of the fingers may be seen, but this is a subjective finding.

Flexor Retinaculum Changes

Volar bowing of the flexor retinaculum is seen secondary to increased pressure within the carpal tunnel ( Fig. 13.3 ). This is assessed at the distal end of the carpal tunnel (hamate–trapezium level). A line joining the hook of the hamate and the tubercle of the trapezium is made. The largest distance from this line to the retinaculum reflects the degree of volar bulging. A value of more than 4 mm is considered significant.

Carpal Tunnel Content

The most common cause of CTS is tenosynovitis of the flexor tendons. Ultrasound demonstrates hypoechoic fluid and synovitis in the tendon sheaths which separate the flexor tendons ( Fig. 13.3 ). Doppler signal depends on the activity of the synovitis.

| When scanning for tenosynovitis in the carpal tunnel, dynamic scanning in the transverse plane during finger flexion and extension helps differentiate the tendons from echogenic synovitis. |

Scanning both proximal and distal to the carpal tunnel is important to avoid false negatives as the synovial fluid accumulates outside the carpal tunnel where there is less resistance to sheath distension.

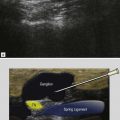

Space occupying lesions within the carpal tunnel are seen well with ultrasound. Ganglia are the commonest and appear as well-defined anechoic masses with no internal vascularity. They usually arise in the deep portion of the tunnel from the wrist joint and displace the median nerve and flexor tendons anteriorly against the flexor retinaculum. Solid tumours include lipomas ( Fig. 13.4 ), neural tumours and giant cell tumours of the tendon sheath. A persistent median artery has been described as a cause of CTS. This is an accessory artery that arises from the ulnar artery in the proximal forearm and may accompany the median nerve through the carpal tunnel. Doppler imaging is useful for identifying it. Acute CTS may be secondary to acute thrombosis of this artery. Following penetrating injury, posttraumatic neuroma, which may affect only a portion of the median nerve, may occur ( Fig. 13.5 ).

Anomalous muscles inside the carpal tunnel relate to the distal insertion of an anomalous muscle belly of the FDS of the index finger, the proximal insertion of a lumbrical muscle or an accessory flexor muscle. Accessory muscles have the typical echotexture of muscles with echogenic linear septa, change shape during contraction and relaxation, and can be seen to enter and exit the tunnel with finger extension and flexion. Abnormal bone extending into the carpal tunnel, such as callus formation or a dislocated lunate, is brightly echogenic with posterior acoustic shadowing.

Treatment for CTS includes wrist splinting, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, intracanal corticosteroid injections and surgical release of the flexor retinaculum. The retinaculum is usually divided close to its ulnar insertion on the hook of hamate.

Assessment of CTS following surgery may be challenging. The median nerve is located in a more superficial and medial location. The resected ends of the flexor retinaculum appear thickened and hypoechoic as they are retracted on either side of the nerve. Persistent symptoms following surgery may be due to incomplete resection of the flexor retinaculum or postoperative fibrous scarring involving the nerve. With incomplete resection, ultrasound may demonstrate continuity of the retinaculum and persistence of the notch sign. Postoperative scar tissue is seen as irregular hypoechoic tissue surrounding the median nerve. Injection around the nerve is said to release some of the adhesions.

Inflammatory Arthritis

Only factors relevant to ultrasound imaging of wrist joint arthritis are highlighted in this section.

Synovitis

A dorsal approach is usually best to assess carpal joint synovitis. The dorsal recesses of the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints are best imaged in the longitudinal plane. Transverse images at these levels are useful to differentiate deep intraarticular fluid and synovitis from superficial extensor tenosynovitis ( Fig. 13.6 ). The distal radioulnar joint is best assessed in the transverse plane, often at a more proximal level than the joint line, where the joint capsule is more likely to distend.