CHAPTER 4 Myositis ossificans is an example of a lesion on which a biopsy should not be performed because its aggressive histologic appearance can often mimic a sarcoma. Unfortunately, radical surgery has been performed based on the histologic appearance of myositis ossificans when the radiologic appearance was diagnostic. The typical radiologic appearance of myositis ossificans is circumferential calcification with a lucent center (Figure 4-1). This is often best appreciated on computed tomography (CT) examination (Figure 4-2). A malignant tumor that mimics myositis ossificans will have an ill-defined periphery and a calcified or ossific center (Figure 4-3). Periosteal reaction can be seen with myositis ossificans or with a tumor. Occasionally the peripheral calcification of myositis ossificans can be difficult to appreciate; in such cases a CT scan or delayed films a week or two later are recommended. Biopsy should be avoided when myositis ossificans is a clinical consideration. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in myositis ossificans can be misleading because the peripheral calcification may not be conspicuous and often has marked soft tissue edema surrounding it (Figure 4-4). FIGURE 4-1 FIGURE 4-2 FIGURE 4-3 FIGURE 4-4 Another posttraumatic entity in which a biopsy can be misleading is an avulsion injury. These injuries can have an aggressive radiographic appearance, but because of their characteristic location at insertion sites (e.g., anteroinferior iliac spine or ischial tuberosity), they should be recognized as benign (Figures 4-5 and 4-6). Again, delayed films of several weeks will usually allow the problem case to become more radiographically and clinically clear. Biopsy can lead to the mistaken diagnosis of a sarcoma and should therefore be avoided. Any area that is undergoing healing can have a high nuclear-chromatin ratio and a high mitotic figure count, thereby occasionally simulating a malignancy. FIGURE 4-5 FIGURE 4-6 A cortical desmoid is a process considered by many to be an avulsion off the medial supracondylar ridge of the distal femur. It occasionally simulates an aggressive lesion radiographically and on biopsy can look malignant.1 In many instances biopsy has led to amputation for this benign, radiographically characteristic lesion (Figures 4-7 and 4-8). Cortical desmoids occur only on the posteromedial epicondyle of the femur. They may or may not be associated with pain and can have increased radionuclide uptake on bone scan. They may or may not exhibit periosteal new bone and usually occur in young people. Biopsy should be avoided in all cases. They are often seen as incidental findings on MRI and have a characteristic appearance (Figure 4-9). FIGURE 4-7 FIGURE 4-8 FIGURE 4-9 Trauma can lead to large cystic geodes or subchondral cysts near joints that can be mistaken for other lytic lesions, and thus a biopsy is performed. Although the biopsy specimen is not likely to mimic a malignant process, it is nevertheless avoidable. Because geodes from degenerative disease almost always are associated with additional findings, such as joint space narrowing, sclerosis, and osteophytes, a diagnosis should be made radiographically (Figures 4-10 and 4-11). However, on occasion the additional findings are subtle and can be missed (Figure 4-12). Geodes can also occur in the setting of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystal disease (also known as CPPD or pseudogout), rheumatoid arthritis, and avascular necrosis.2 FIGURE 4-10 FIGURE 4-11 FIGURE 4-12 An entity that is often confused with metastatic disease to the spine is discogenic vertebral disease. It can mimic metastatic disease radiographically and clinically, and unless the radiologist is familiar with this process, it can lead to an unnecessary biopsy.3,4 Discogenic vertebral disease most often is sclerotic and focal (Figure 4-13). It is adjacent to an end-plate, and the associated disc space should be narrow. Osteophytosis is invariably present. It represents a variant of a Schmorl’s node and should not be confused with a metastatic focus. On occasion it can be lytic or even mixed lytic-sclerotic. The typical clinical presentation is a middle-aged woman with chronic low back pain. Old films often confirm the benign nature of this process. In the setting of disc space narrowing and osteophytosis, a biopsy of focal sclerosis adjacent to an end-plate should not be performed. FIGURE 4-13 Occasionally a fracture will be the cause of extensive osteosclerosis and periostitis, which can mimic a primary bone tumor (Figure 4-14). Lack of immobilization can result in exuberant callus, which can be misinterpreted as aggressive periostitis or even tumor new bone. Biopsy results in such a case might resemble those of a malignant lesion. Therefore any case associated with trauma should be carefully reviewed for a fracture. FIGURE 4-14

“Don’t touch” lesions

Posttraumatic lesions

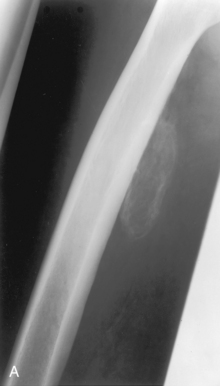

Myositis ossificans. A, A plain film of the femur in this patient, who presented with a soft tissue mass, shows a calcific density adjacent to the posterior cortex of the femur that is calcified primarily in its periphery. From seeing the plain film alone, it should not be difficult to say that this is peripheral, circumferential calcification; nevertheless, a CT scan was obtained (B) and shows that the calcification is unequivocally peripheral. This is virtually diagnostic of myositis ossificans.

Myositis ossificans. A, A plain film of the femur in this patient, who presented with a soft tissue mass, shows a calcific density adjacent to the posterior cortex of the femur that is calcified primarily in its periphery. From seeing the plain film alone, it should not be difficult to say that this is peripheral, circumferential calcification; nevertheless, a CT scan was obtained (B) and shows that the calcification is unequivocally peripheral. This is virtually diagnostic of myositis ossificans.

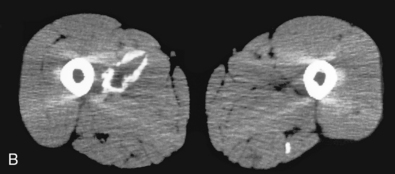

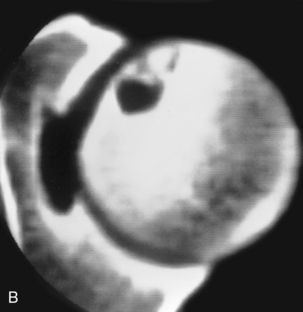

Myositis ossificans. A, Hazy calcification is seen adjacent to the humeral shaft, with underlying periosteal reaction noted. It is difficult to ascertain whether the calcification is circumferential. B, A CT scan through this mass shows that the calcification is unequivocally circumferential, making the diagnosis of myositis ossificans a certainty.

Myositis ossificans. A, Hazy calcification is seen adjacent to the humeral shaft, with underlying periosteal reaction noted. It is difficult to ascertain whether the calcification is circumferential. B, A CT scan through this mass shows that the calcification is unequivocally circumferential, making the diagnosis of myositis ossificans a certainty.

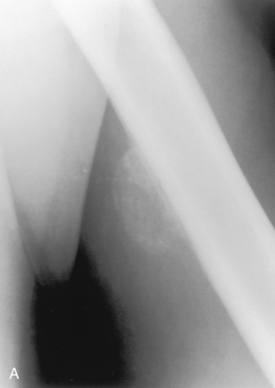

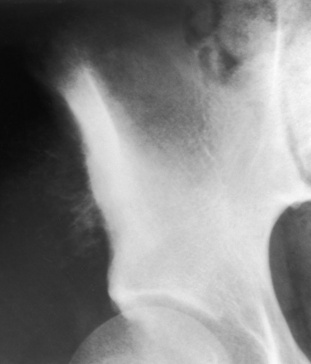

Osteogenic sarcoma. Hazy, ill-defined calcification seen adjacent to the iliac wing in this patient can be definitively ascertained from the plain film not to be circumferential. Even though a history of trauma was obtained in this case, myositis ossificans is not a consideration with this appearance of calcification. Biopsy showed this to be an osteogenic sarcoma.

Osteogenic sarcoma. Hazy, ill-defined calcification seen adjacent to the iliac wing in this patient can be definitively ascertained from the plain film not to be circumferential. Even though a history of trauma was obtained in this case, myositis ossificans is not a consideration with this appearance of calcification. Biopsy showed this to be an osteogenic sarcoma.

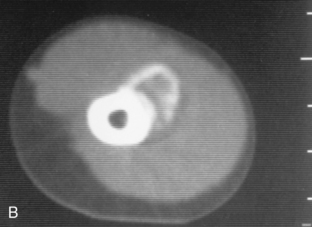

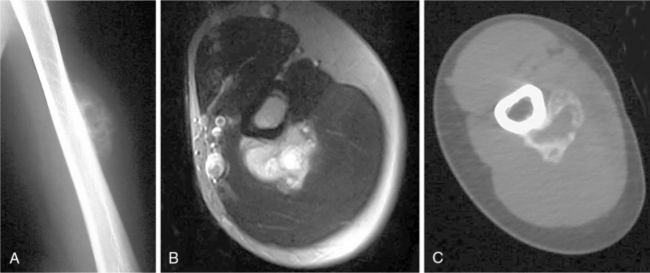

Myositis ossificans. A, A plain film of the humerus in this 30-year-old man shows a calcific mass adjacent to the diaphysis of the humerus. The calcification is not clearly peripheral in nature, although the central portion is less well mineralized. B, An axial T2-weighted image through the mass shows only a high-signal mass without evidence of calcification. C, A CT scan through the mass demonstrates the typical peripheral calcification, which is virtually pathognomonic for myositis ossificans.

Myositis ossificans. A, A plain film of the humerus in this 30-year-old man shows a calcific mass adjacent to the diaphysis of the humerus. The calcification is not clearly peripheral in nature, although the central portion is less well mineralized. B, An axial T2-weighted image through the mass shows only a high-signal mass without evidence of calcification. C, A CT scan through the mass demonstrates the typical peripheral calcification, which is virtually pathognomonic for myositis ossificans.

Avulsion injury. Cortical irregularity (arrows) at the ischial tuberosity in this patient with pain over this region raises the question of possible tumor. This is a classic appearance, however, for an avulsion injury from this region, and a biopsy should be avoided.

Avulsion injury. Cortical irregularity (arrows) at the ischial tuberosity in this patient with pain over this region raises the question of possible tumor. This is a classic appearance, however, for an avulsion injury from this region, and a biopsy should be avoided.

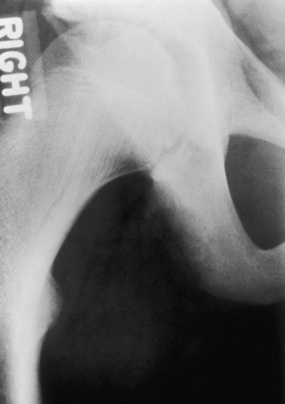

Avulsion injury. Cortical irregularity with a Codman’s triangle of periostitis is seen along the ischial tuberosity. This was at first thought to represent a malignancy. Because of the characteristic location, an avulsion injury was considered, and the lesion was observed. It healed without sequelae.

Avulsion injury. Cortical irregularity with a Codman’s triangle of periostitis is seen along the ischial tuberosity. This was at first thought to represent a malignancy. Because of the characteristic location, an avulsion injury was considered, and the lesion was observed. It healed without sequelae.

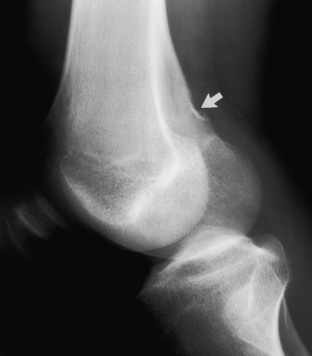

Cortical desmoid. A focal cortical irregularity is seen in the posterior aspect of the femur (arrow) with adjacent periostitis noted. Although a tumor such as an early parosteal osteosarcoma could perhaps have this appearance, the location and appearance are characteristic of a cortical desmoid, and a biopsy should not be performed.

Cortical desmoid. A focal cortical irregularity is seen in the posterior aspect of the femur (arrow) with adjacent periostitis noted. Although a tumor such as an early parosteal osteosarcoma could perhaps have this appearance, the location and appearance are characteristic of a cortical desmoid, and a biopsy should not be performed.

Cortical desmoid. A well-defined cortical defect is seen in the posterior distal femur (arrow), which is a common appearance for a fairly well-healed cortical desmoid.

Cortical desmoid. A well-defined cortical defect is seen in the posterior distal femur (arrow), which is a common appearance for a fairly well-healed cortical desmoid.

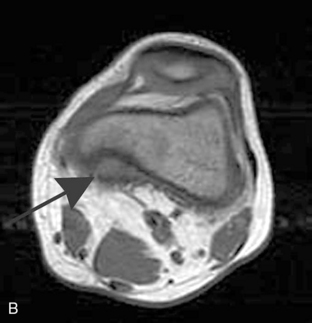

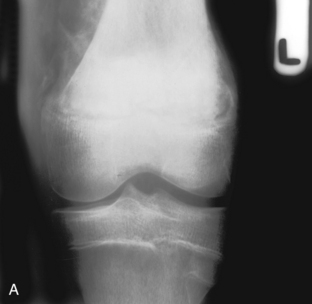

Cortical desmoid. A, An anteroposterior film of the knee in a child shows a faint lytic lesion (arrows) in the medial aspect of the distal femur. Axial T1-weighted (B) and T2-weighted (C) images through the lesion show a cortically based process (arrows) in the medial supracondylar ridge, which is characteristic for a cortical desmoid.

Cortical desmoid. A, An anteroposterior film of the knee in a child shows a faint lytic lesion (arrows) in the medial aspect of the distal femur. Axial T1-weighted (B) and T2-weighted (C) images through the lesion show a cortically based process (arrows) in the medial supracondylar ridge, which is characteristic for a cortical desmoid.

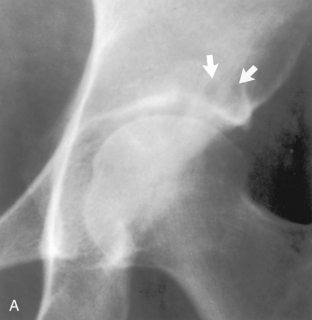

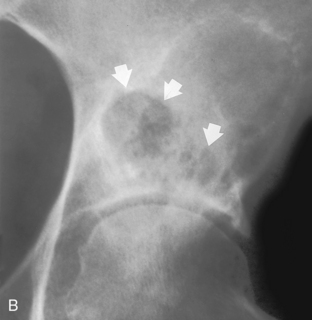

Geode. A, A plain film of the hip in this older patient with hip pain shows in the supraacetabular region a lytic lesion (arrows), which has a benign appearance. Mild osteoarthritis was thought to be present (when compared with the opposite hip, joint space narrowing and minimal sclerosis were seen); hence this was believed to be a subchondral cyst or geode. B, Several years later the same hip shows a large lytic lesion (arrows) that still appears benign. The osteoarthritis has increased in severity. However, because of the growth of the lesion, a biopsy was performed and it was found to be a geode. A biopsy should have been avoided.

Geode. A, A plain film of the hip in this older patient with hip pain shows in the supraacetabular region a lytic lesion (arrows), which has a benign appearance. Mild osteoarthritis was thought to be present (when compared with the opposite hip, joint space narrowing and minimal sclerosis were seen); hence this was believed to be a subchondral cyst or geode. B, Several years later the same hip shows a large lytic lesion (arrows) that still appears benign. The osteoarthritis has increased in severity. However, because of the growth of the lesion, a biopsy was performed and it was found to be a geode. A biopsy should have been avoided.

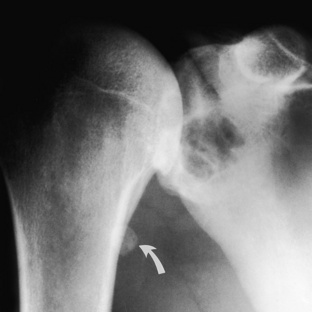

Geode. A large cystic lesion was found in the shoulder in this middle-aged weight lifter, and the possibility of a metastatic process was considered. Because the humeral head has sclerosis and osteophytosis, as well as a loose body in the joint (arrow), degenerative disease of the shoulder was diagnosed; this makes the cystic lesion almost certainly a geode or subchondral cyst, which made a biopsy unnecessary.

Geode. A large cystic lesion was found in the shoulder in this middle-aged weight lifter, and the possibility of a metastatic process was considered. Because the humeral head has sclerosis and osteophytosis, as well as a loose body in the joint (arrow), degenerative disease of the shoulder was diagnosed; this makes the cystic lesion almost certainly a geode or subchondral cyst, which made a biopsy unnecessary.

Geode. A, A cystic lesion was noted in the femoral head (arrows) of a young male with a painful hip. B, A CT scan through this area shows the subarticular nature and adjacent sclerosis. The differential diagnosis of infection, eosinophilic granuloma, and chondroblastoma was given. A ring of osteophytes (open arrow heads) was noted in retrospect on the plain film (A) in the subcapital region, which indicates degenerative disease of the hip. This is an extremely unusual presentation in a healthy 20-year-old male; however, it makes the lytic lesion in the femoral head almost certainly a subchondral cyst or geode. This was an active soccer player who had been playing with pain in his hip for several years after an injury that had caused the degenerative disease. Unfortunately a biopsy was performed anyway, and a subchondral cyst or geode was confirmed.

Geode. A, A cystic lesion was noted in the femoral head (arrows) of a young male with a painful hip. B, A CT scan through this area shows the subarticular nature and adjacent sclerosis. The differential diagnosis of infection, eosinophilic granuloma, and chondroblastoma was given. A ring of osteophytes (open arrow heads) was noted in retrospect on the plain film (A) in the subcapital region, which indicates degenerative disease of the hip. This is an extremely unusual presentation in a healthy 20-year-old male; however, it makes the lytic lesion in the femoral head almost certainly a subchondral cyst or geode. This was an active soccer player who had been playing with pain in his hip for several years after an injury that had caused the degenerative disease. Unfortunately a biopsy was performed anyway, and a subchondral cyst or geode was confirmed.

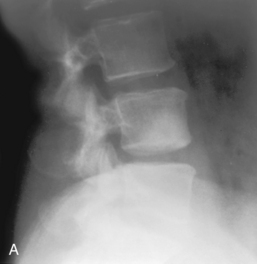

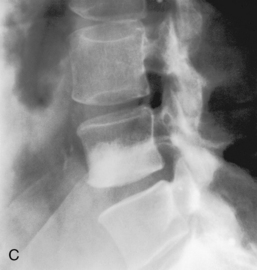

Discogenic vertebral sclerosis. A–C, These films all show patients with sclerosis on the inferior portion of the L4 vertebral body associated with minimal osteophytosis and joint space narrowing at the adjacent disc space. This is the classic appearance for discogenic vertebral sclerosis, and a biopsy to rule out metastatic disease should not be performed.

Discogenic vertebral sclerosis. A–C, These films all show patients with sclerosis on the inferior portion of the L4 vertebral body associated with minimal osteophytosis and joint space narrowing at the adjacent disc space. This is the classic appearance for discogenic vertebral sclerosis, and a biopsy to rule out metastatic disease should not be performed.

Fracture mimicking osteosarcoma. A, This 16-year-old had experienced pain around the knee for 2 weeks before these radiographs were taken. The knee films showed diffuse sclerosis and extensive periostitis about the distal femur, which was believed to be characteristic for an osteogenic sarcoma. The periosteal reaction, however, was believed to be much too thick, dense, and wavy to represent malignant type of periostitis. B, A small offset of the epiphysis can be seen (arrow), which indicates an epiphyseal slippage consistent with a Salter epiphyseal fracture. The patient had fallen off his bicycle and fractured his femur, yet he continued to be active. The lack of immobility caused exuberant periostitis or callus with a large amount of reactive sclerosis, all of which mimicked an osteogenic sarcoma.

Fracture mimicking osteosarcoma. A, This 16-year-old had experienced pain around the knee for 2 weeks before these radiographs were taken. The knee films showed diffuse sclerosis and extensive periostitis about the distal femur, which was believed to be characteristic for an osteogenic sarcoma. The periosteal reaction, however, was believed to be much too thick, dense, and wavy to represent malignant type of periostitis. B, A small offset of the epiphysis can be seen (arrow), which indicates an epiphyseal slippage consistent with a Salter epiphyseal fracture. The patient had fallen off his bicycle and fractured his femur, yet he continued to be active. The lack of immobility caused exuberant periostitis or callus with a large amount of reactive sclerosis, all of which mimicked an osteogenic sarcoma.![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine