20 | Doppler Ultrasound in Gynecology |

The potential of Doppler ultrasound examination of the female pelvis has been greatly expanded since the introduction of color Doppler, as it is now possible simultaneously to display the anatomical structures in B-mode and blood flow in color. Ultrasound probes that include pulsed Doppler or color Doppler to display the microcirculation have been available to practitioners for more than a decade. Now that measurement of blood perfusion, though still debated critically, has become established in obstetrics relatively rapidly, this chapter will attempt to present the current status of Doppler ultrasound in gynecology.

In the course of the menstrual cycle marked changes occur in the female sex organs, including the breast and in the internal genital region.

Distinct perfusion changes can also be recorded as part of the physiological maturation and aging of the female genital organs from the beginning of puberty into old age.

Finally, distinct perfusion changes are found in the organs in the course of a number of benign inflammatory conditions and during the development of malignant tumors.

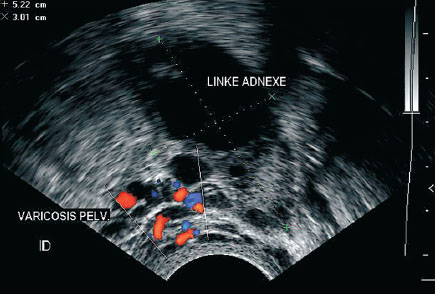

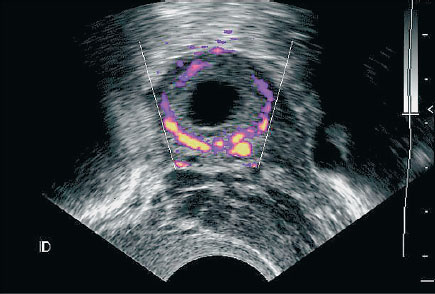

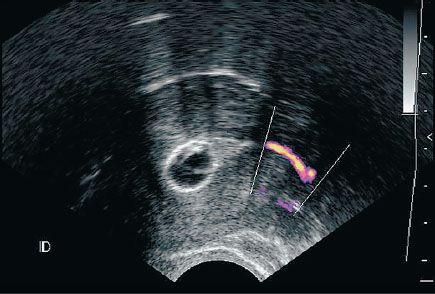

These considerations clearly show that the early detection of neoplasms and the assessment of the significance of undefined adnexal findings can be improved considerably by evaluating organ perfusion, adding color-coded Doppler ultrasound to the purely morphological descriptions of structural changes used previously. For instance, the differential diagnosis of pelvic varices, which previously was difficult, can be facilitated considerably by the use of color Doppler (Figs. 20.1, 20.2).

Fig. 20.1 Inconclusive cystic finding adjacent to the ovary.

Fig. 20.2 Display of vascular perfusion with pelvic varicosities.

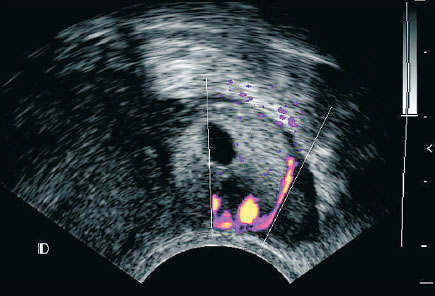

Fig. 20.3 Ectopic pregnancy with characteristic halo due to intense vascularization of the chorion.

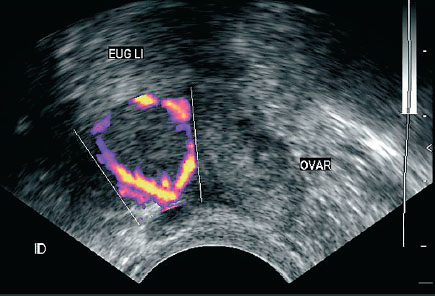

Fig. 20.4 Ovary with adjacent ectopic pregnancy showing strong vascularization.

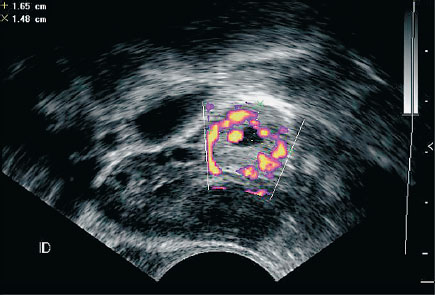

Similar considerations apply to the early diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy (Figs. 20.3–20.5) and the monitoring of the course of an ectopic pregnancy by medical treatment with systematically administered methotrexate. Note that the perfusion of the corpus lu-teum is also profuse, so that a suspected ectopic pregnancy could be confused with a normally developed corpus luteum (Fig. 20.6). Hence it is important to display both organs, the ovary and the uterine tube containing the ectopic pregnancy, side by side to ensure the proper identification of the ectopic pregnancy. In this case uncritical application of color Doppler can induce a diagnostic error.

Fig. 20.5 Intensely vascularized ectopic pregnancy adjacent to the ovary.

Fig. 20.6 Corpus luteum with similarly intense perfusion due to neovascularization.

When uterine fibroids are treated medically with gonadotropic-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, Doppler ultrasound display of a reduction in perfusion can supplement the reduction in size.

Other applications of pulsed and color-coded Doppler ultrasound include the demonstration and documentation of tubal hydroperturbation by ultrasound contrast media as part of a diagnostic workup for sterility (Fig. 20.7).

It should be noted that the premature uncritical introduction into clinical practice of a new method such as color Doppler ultrasound, when not adequately founded on research, can entail considerable risk. This is especially true when estimating its validity and when planning treatment based on this. In this connection special mention should be made of the risk of laparoscopic surgery when an unexpected adnexal malignancy is found.

Fig. 20.7 Flow of contrast medium through the uterine tube displayed by color Doppler.

Tumor Angiogenesis

As early as 1907 Goldman (The Growth of Malignant Disease in Man with Reference to Vascular System), working from arteriographic studies of tumor specimens (Fig 20.8), described the development of newly formed “tumor vessels” in the periphery of malignant tumors. Many decades later Folkman (1974) postulated that tumor growth was only possible when new vessels are formed in the vicinity of the tumor. In 1971 Folkman et al. were able to discover the underlying mechanisms of this activity by describing and demonstrating tumor-angiogenesis factors. Increasing new formation of blood vessels can now be demonstrated in tumors over 3–5 mm in diameter.

However, new vascularization does not always constitute an unambiguous criterion for the formation of a tumor, since new vascularizations and changes in tissue perfusion can also occur during physiological and benign processes, such as for instance wound healing, ectopic pregnancy (cf. above) and in inflammatory processes. If in a case presenting a sonographically suspect adnexal finding no vessel can be displayed by ultrasound, the following should be considered:

Flow may be present in the tumor, but very slow due to small vascular diameters. In this case the flow may not reach the sensitivity threshold of the instrument. Thus, there may be a change in perfu-sion, but the instrument cannot register it for technical reasons. The introduction of intravenous ultrasonic contrast media improves the signal in such cases and so leads to improvement by displaying even the smallest vessels. Another possibility suggested by Sohn et al. (1993) is to raise the perfusion briefly and artificially by raising the blood pressure. This may, for instance, be achieved without risk by a controlled physical load.

Flow may be present in the tumor, but very slow due to small vascular diameters. In this case the flow may not reach the sensitivity threshold of the instrument. Thus, there may be a change in perfu-sion, but the instrument cannot register it for technical reasons. The introduction of intravenous ultrasonic contrast media improves the signal in such cases and so leads to improvement by displaying even the smallest vessels. Another possibility suggested by Sohn et al. (1993) is to raise the perfusion briefly and artificially by raising the blood pressure. This may, for instance, be achieved without risk by a controlled physical load.

Since tumors are often only poorly vascularized in their core, display of tumor vascularization due to angiogenesis may only be possible in the immediate periphery of the tumor. This effect has been documented especially in the examination of mammary tumors.

Since tumors are often only poorly vascularized in their core, display of tumor vascularization due to angiogenesis may only be possible in the immediate periphery of the tumor. This effect has been documented especially in the examination of mammary tumors.

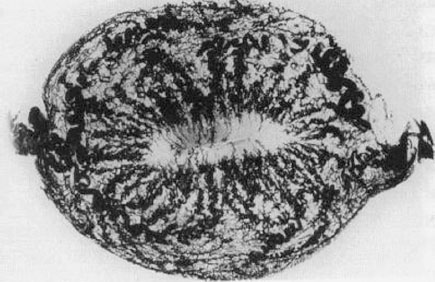

During rapidly increasing tumor growth the center first becomes strongly vascularized. There follows a secondary central compression of the newly formed vessels (Fig. 20.9). The consequence of such diminished central tissue perfusion may be necrosis. Thus, in the core of the tumor avascular areas may alternate with some that are well perfused and necrotic. Such changes are not, however, pathog-nomic for malignant tumors: Central necroses may be observed not only in rapidly growing malignant tumors, but are also characteristic of rapidly growing fibroid tumors.

During rapidly increasing tumor growth the center first becomes strongly vascularized. There follows a secondary central compression of the newly formed vessels (Fig. 20.9). The consequence of such diminished central tissue perfusion may be necrosis. Thus, in the core of the tumor avascular areas may alternate with some that are well perfused and necrotic. Such changes are not, however, pathog-nomic for malignant tumors: Central necroses may be observed not only in rapidly growing malignant tumors, but are also characteristic of rapidly growing fibroid tumors.

Essential Considerations for Clinical Practice

Complete absence of connected vessels or sporadic color pixels in a display speaks against the presence of angiogenesis associated with a tumor and hence at the same time against the presence of a malignant tumor.

Fig. 20.8 Arteriographic cast of the uterus displaying the blood vessels, modified after Fleischer et al.

Fig. 20.9 Marginal blood vessels in a mammary carcinoma.

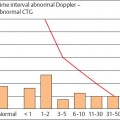

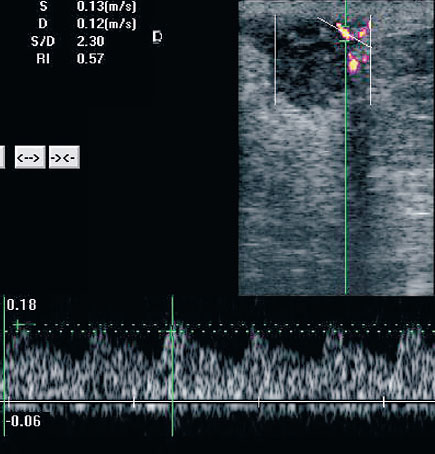

If the display of a suspicious area shows multiple signals with a variable, but above all a low resistance index (RI), such abnormal perfusion tends to favor the presence of a malignant tumor.

Examination Procedure and Instrumentation for Ultrasound Diagnosis of the Pelvis

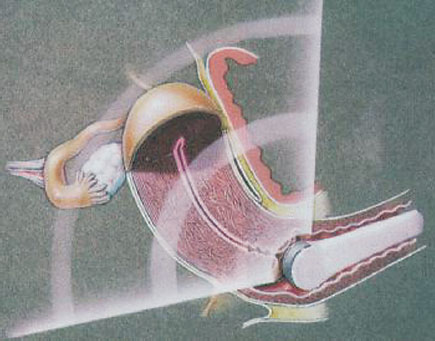

Besides a valid clinical question, Doppler examination of the internal genital area requires in every case a vaginal examination and B-mode vaginal sonography for a three-dimensional view of the relations of the organs (Fig. 20.10).

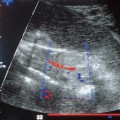

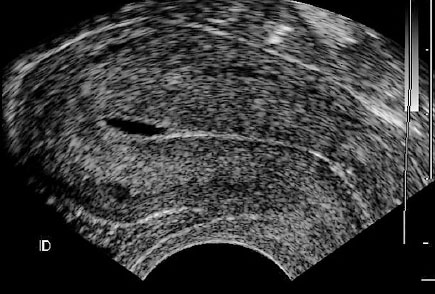

In B-mode sonography the uterus is imaged first for orientation and is displayed in longitudinal and cross section (Fig. 20.11). The display should be examined for structural changes in the myometrium and the endometrium, and for free fluid in the pouch of Douglas. The thickness and condition of the endometrium should be recorded. The search for the adnexa begins laterally at the pelvic wall near the iliac vessels. The search may be made difficult by reduced ovarian volume and superposition of gas-filled intestinal loops, especially after menopause. The ovary is localized and its morphology recorded (size or volume, follicles, cystic or solid constituents), using a score if necessary. Its vascularization can then be displayed by color Doppler.

Depending on the diagnostic question, a variety of Doppler systems may be used for this purpose. If the large vessels (iliac a.) are to be displayed, a high velocity up to 1 m/s must be taken into account: Perfusion in this case can be displayed with the usual direction-dependent, frequency-coded, color flow mapping (CFM) mode. These vessels are displayed easily because of the high intensity and high pulsatility of the flow signals. In contrast, the actual ovarian vessels are often difficult to display. The right ovarian a. originates from the right renal a., the left from the aorta. However, the ovarian aa. are of subordinate significance in the evaluation of the ovarian perfusion proper, since in clinical practice only vessels within the limits of the organ itself can be assigned to that organ with any certainty. When displaying the actual perfusion of an organ or establishing the presence of tumor vessels, anatomical features such as very small vascular diameters and very slow blood flows must be taken into account. Hence a display using an amplitude-coded, direction-dependent power Doppler is preferred, for in favorable situations this allows displays of very slow flows of as low as a few millimeters per second. In such cases the small arteries with low vascular resistance inside the organ are displayed rather than the larger vessels supplying the organ.

Fig. 20.10 Three-dimensional representation of the pelvic organs.

Fig. 20.11 Longitudinal section through the uterus showing thin endometrium, scanty serometra.

Evaluation

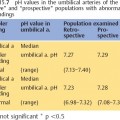

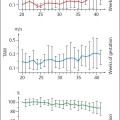

This addresses in the first place qualitative impressions of the vascularization of the organ. The record should include the number and density of the color pixels displayed, the diameter of the vessel, the number of vessels displayed, the presence and number of vascular branchings. Next the sample volume is placed in the vessel to be examined or the abnormal color pixel group, and the pulsed Doppler inserted. In quantitative measurements, besides measuring flow velocity, the derived flow curve is described by the use of indices; the most commonly used indices are the RI (Vmax – Vmin/Vmax) and the pulsatility index (PI) (Vmax – Vmin/Vtime average).

According to studies by Valentin et al. (1994) and Carter et al. (1995), it is better to dispense with the precise alignment of the angle of incidence, since the direction of the tumor vessels can often not be determined.

Statistical analysis of results by Prömpler’s group (1994) showed that the values RI and PI are highly correlated. The correlation coefficient was 0.99. The diagnostic significance of both parameters seems to be equivalent. Consequently in our clinic we prefer documenting the RI because it is easier to determine and plot.

Ovarian Diagnosis

Conventional Ultrasound Examination of the Ovary: Procedure and Results

Since 1983 Campbell et al. have been reporting continuously on a voluntary screening program using transabdominal sonography on 5497 women. Asymptomatic women only received annual ultrasound. In 1990 they published these results: 336 (5.9%) women were found to have abnormal sonograms. In the subsequent exploratory operation five women had ovarian carcinoma. Hence detection of a malignant ovarian tumor by ultrasound examination carries a positive predictive value or accuracy of merely 1:26. The probability of discovering a primary ovarian carcinoma was therefore just 1:50.

When ultrasound screening by transvaginal sonography was performed for ovarian carcinoma, several criteria were evaluated. Those given special attention included:

Ovarian size (Campbell et al. 1989, Duda et al. 1990): Premenopausal volume >18 mL, postmenopausal volume >8 mL were considered suspicious. As a general rule length × breadth × height × 0.53 was used as an approximate estimate of volume.

Ovarian size (Campbell et al. 1989, Duda et al. 1990): Premenopausal volume >18 mL, postmenopausal volume >8 mL were considered suspicious. As a general rule length × breadth × height × 0.53 was used as an approximate estimate of volume.

Pathological structure of the ovary: The evaluation included changes in echogenicity, the appearance of cystic formations, appearance of solid parts, and blurred contours (Fig. 20.12). All study groups agree that the appearance of a solid segment in a cystic adnexal structure is the criterion that best distinguishes benign from malignant tumors.

Pathological structure of the ovary: The evaluation included changes in echogenicity, the appearance of cystic formations, appearance of solid parts, and blurred contours (Fig. 20.12). All study groups agree that the appearance of a solid segment in a cystic adnexal structure is the criterion that best distinguishes benign from malignant tumors.

Difference in size of the ovaries (Campbell et al. 1989, Duda et al. 1990): Using this criterion an ovary that was more than double the size of the contralateral ovary was considered suspicious.

Difference in size of the ovaries (Campbell et al. 1989, Duda et al. 1990): Using this criterion an ovary that was more than double the size of the contralateral ovary was considered suspicious.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree