- Commonly present following a FOOSH

- Injury patterns in children differ from adults due to the epiphyseal and apophyseal centres

- An understanding of age of ossification of these centres is important

- A methodical review, including lines and congruity of the joint spaces, is important to avoid missing injuries

Elbow injuries are common and usually result from a fall onto an outstretched hand (FOOSH). Detecting and interpreting abnormal features on radiographs can be difficult and challenging—particularly in children because they have multiple epiphyseal and apophyseal growth centres. An understanding of normal anatomy and adoption of a systematic approach when assessing the radiographs is essential. MRI, CT and US are not necessary in the acute presentation.

Anatomy

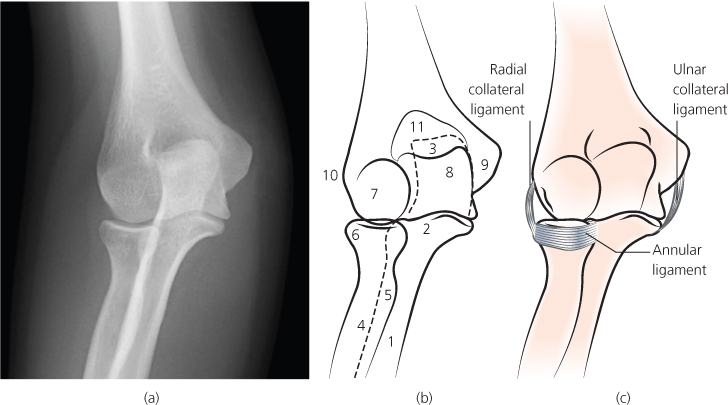

The elbow (Figures 3.1a–c and 3.2a,b) is a hinge joint that consists of three articulations within a single synovial space. The lower end of the humerus is composed of two different shapes. On the lateral side, a partly spherical contour (capitellum) articulates with the concave articular surface of the head of the radius. On the medial side, a notched medial contour (trochlea) articulates with the ulna.

Figure 3.1 (a)–(c) Normal anteroposterior view of right elbow and ligaments. 1, Ulna; 2, coronoid process; 3, olecranon; 4, proximal radius; 5, radial tuberosity; 6, radial head; 7, capitellum; 8, trochlea; 9, medial epicondyle; 10, lateral epicondyle; 11, coronoid fossa; 12, olecranon fossa.

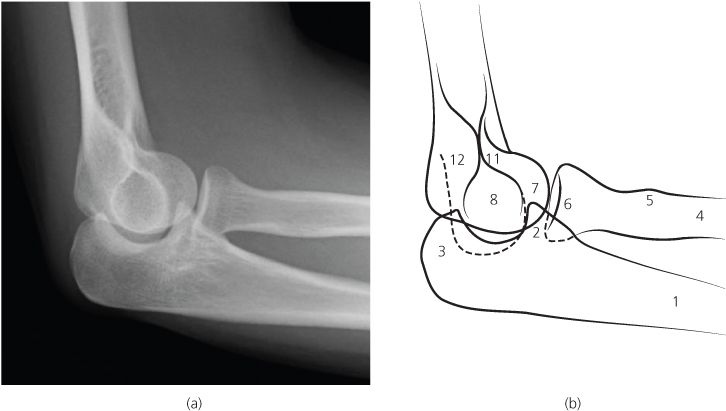

Figure 3.2 (a),(b) Normal lateral elbow (for explanation of numbers see legend for Figure 3.1).

The stability of the radioulnar articulation is maintained by the annular ligament. This is a sling that holds the head of the radius against the ulna. The radial head is free to rotate within this sling.

The joint capsule comprises an inner layer of synovium, a layer of fat and an outer layer of fibrous tissue. The layer of fat results in anterior and posterior fat pads. These lie outside the synovial lining of the joint, but within the joint capsule. The anterior fat pad is radiographically visible in almost all normal elbows. The posterior fat pad lies deep in the olecranon fossa and is never visible in the flexed position unless a large effusion or haemarthrosis displaces it out of the fossa.

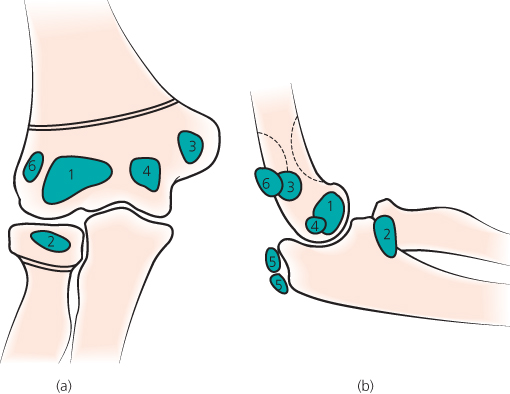

Figure 3.3 (a),(b) Diagram of ossification centres. 1, Capitellum; 2, radial head; 3, medial or internal epicondyle; 4, trochlea; 5, olecranon; 6, lateral or external epicondyle.

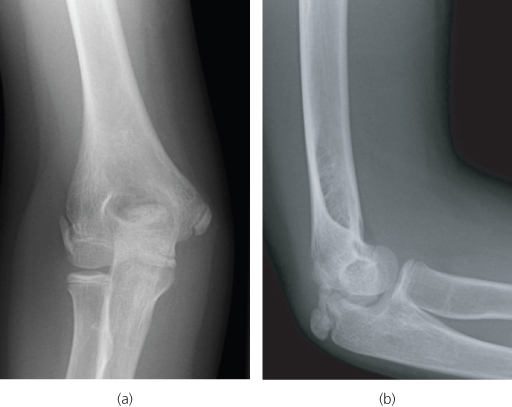

Figure 3.4 (a),(b) Normal AP and lateral elbow in a 12-year-old boy.

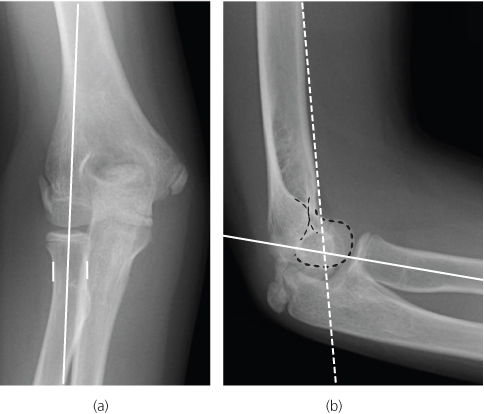

Figure 3.5 (a) Radiocapitellar line (RCL)—white line; (b) anterior humeral line (AHL)—white dotted line.

Children

Unfused ossification centres in children (Figures 3.3a,b and 3.4a,b) lead to a particular set of injuries (Table 3.1). Children have three epiphyseal ossification centres (capitellum, trochlea and radius) and three apophyseal centres (internal epicondyle, external epicondyle and olecranon). These appear (begin to ossify) at different ages. The trochlear and olecranon centres are often multicentric and should not be mistaken for fracture fragments. If the appearance is confusing, refer to a textbook of normal variants or seek a specialist opinion. If necessary, radiograph the opposite uninjured elbow for comparison.

Table 3.1 Particular problems in children.

| Potential traps | Helpful hints |

| Ossifying secondary centres can cause confusion, particularly when a centre shows multicentric ossification | Doubt or confusion can usually be resolved with the help of a comparison radiograph of the opposite uninjured elbow |

| An incompletely fused growth plate can mimic a fracture | |

| A fracture involving the lateral condyle can be dismissed erroneously as the normal apophyseal growth plate | |

| A pulled off medial epicondyle may be trapped in the joint. It can be mistaken for the normal trochlea ossification centre. This lesion is rare but is a recognised complication of a dislocated elbow—even one that has reduced spontaneously | Suspect this injury if there is slight widening of the medial joint space on the anteroposterior projection |

| Remember CRITOE…and the ossified trochlea never appears before the ossified internal epicondyle |

The acronym CRITOE (or CRITOL) (capitellum, radial head, internal epicondyle, trochlea, olecranon, external or lateral epicondyle) lists the most common sequence in which the secondary ossification centres appear on the radiograph (Table 3.2). Although the CRITOE order is the most common sequence, individual variation does occur. Nevertheless, one part of the sequence never varies: the internal epicondyle always ossifies before the trochlea. This has particular diagnostic relevance to an uncommon, but clinically important, injury involving major displacement of the internal epicondyle ossification centre.

Table 3.2 Approximate age at which secondary ossification centres appear on radiographs (CRITOE).

| Centre | Appearsa | Age (years) |

| Capitellum | First | 1 |

| Radial head | Second | 3–6 |

| Internal epicondyle always before the… | Third | 4–7 |

| Trochlea | Fourth | 7–10 |

| Olecranon | Fifth | 6–10 |

| External epicondyle | Sixth | 11–14 |

NB The sequence in which the secondary centres appear (above) is the most common sequence. There are occasional individual variations.

ABCs systematic assessment

- Adequacy

- Alignment

- Bones

- Congruity

- Soft tissues

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree