Layer

Histology

Features relevant to imaging

Endometrium

Single-layer columnar epithelium resting on a layer of connective tissue that varies in thickness throughout the menstrual cycle

Thickness varies throughout menstrual cycle (thinnest just after menstruation and gradual thickening over the cycle)

Myometrium

Smooth muscle layer; the innermost aspect, the “junctional zone,” constitutes the interface between the myometrium and endometrium

May appear indistinct or shrink during menstruation; the junctional zone may thicken (paralleling changes in endometrial thickness, but to a lesser degree) and mimic uterine pathology (e.g., adenomyosis)

Perimetrium

Serosal layer covering the dorsal and ventral aspects of the uterus

Table 2.2

Factors affecting endometrial thickness

Factor | Comments |

|---|---|

Physiologic | In premenopausal women, endometrial cavity is thinnest just after menstruation and gradually thickens over the menstrual cycle |

Hormone replacement therapy | Biopsy is warranted if endometrial thickness is >8 mm if the patient is asymptomatic or ≥5 mm in the presence of postmenopausal bleeding |

Endometrial hyperplasia/polyp | Imaging cannot differentiate endometrial hyperplasia or polyps from stage IA endometrial cancer; the most helpful feature to exclude cancer is the absence of myometrial or cervical invasion |

Table 2.3

Imaging techniques used for evaluation of the endometrium

Technique | Main use | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

Ultrasound | First-line evaluation of uterine pathology | Readily available | Operator-dependent |

Cost-effective | Limited accuracy in staging endometrial cancer | ||

Usually well tolerated | |||

CT | Staging of endometrial cancer | Fast | Involves ionizing radiation |

Reproducible | Contrast resolution is not as good as ultrasound or MRI | ||

More widely available than MRI | |||

MRI | Most accurate for local staging (e.g., depth of myometrial invasion) and evaluation of recurrence | Superb contrast resolution | More expensive and less readily available than ultrasound or CT |

No ionizing radiation | |||

Positron emission tomography (PET) | Evaluation of metastatic disease | Depicts both anatomy and function | Radiation from both CT and PET component of the examination |

Whole-body evaluation |

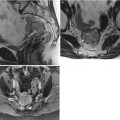

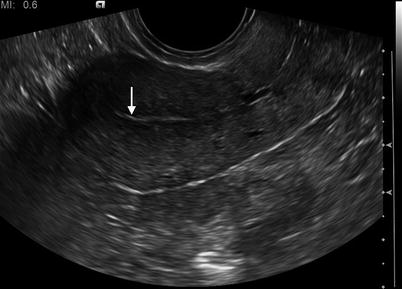

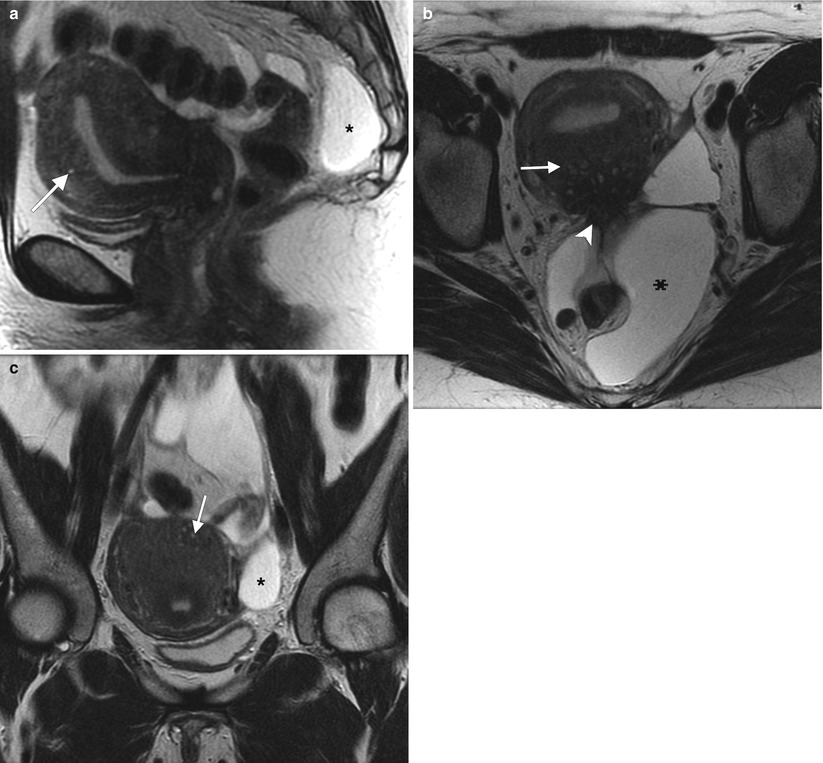

Fig. 2.1

Zonal anatomy of the normal uterus. T2-weighted sagittal (a), axial (b), and coronal (c) images demonstrate the normal uterine zonal anatomy in a premenopausal woman, including the endometrium (arrows), junctional zone (arrowheads), and outer myometrium (asterisks)

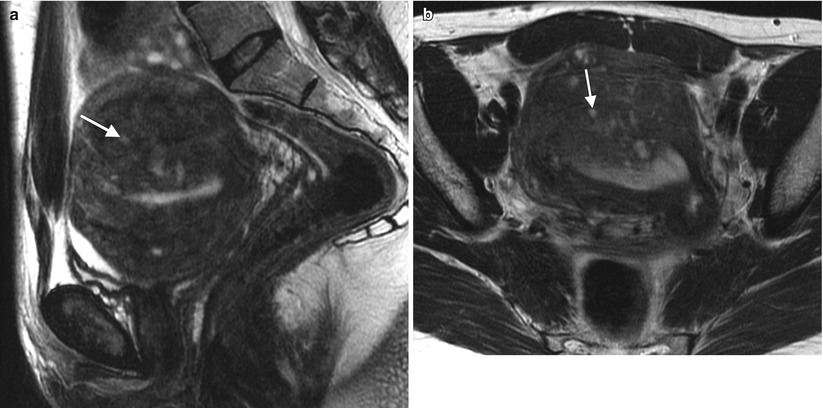

Fig. 2.2

Longitudinal 2-D transvaginal ultrasound image of the normal endometrium (arrow). The hallmark of endometrial cancer on imaging is thickening of the endometrial cavity. Varying size cutoffs have been proposed: the prevalence of endometrial cancer has been reported to be 0.6 % when the endometrial thickness is <5 mm, compared with 19 % when the endometrial thickness is 5 mm or more [5]. However, endometrial thickening may be present in many physiologic and benign conditions

2.2 Benign Uterine Pathology

Benign pathologies to be considered in symptomatic women include adenomyosis, leiomyomata (fibroids), and intravenous leiomyomatosis.

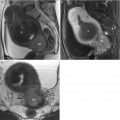

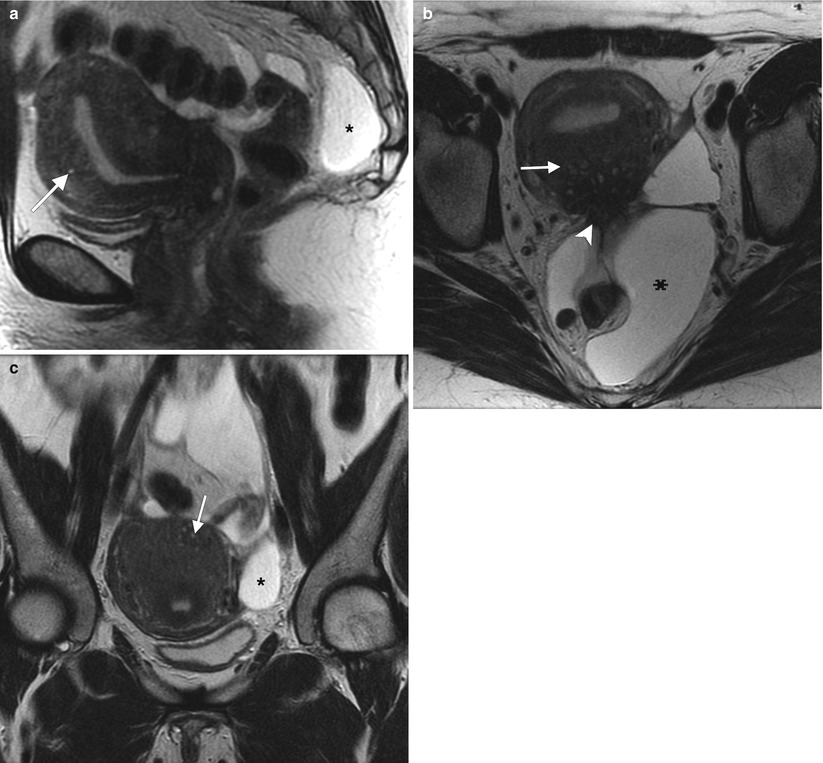

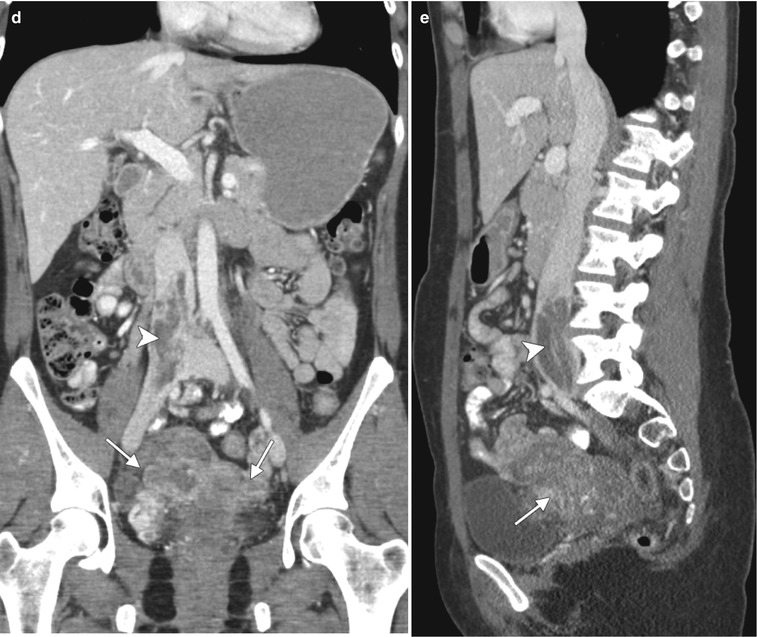

Fig. 2.3

Adenomyosis is the term used for the presence of endometrial glands within the myometrium. The most common imaging findings are thickening of the junctional zone (>12 mm on the midsagittal plane on T2-weighted MRI has an accuracy of 85 % and specificity of 96 % [6]) and the presence of “microcysts” in the myometrium measuring 3–7 mm. Pitfall: Physiologic myometrial contractions may simulate the presence of adenomyosis. The use of antiperistaltic medication or repeat imaging a few minutes after the initial acquisition have been proposed as methods to circumvent this issue, as myometrial contractions should subside and adenomyosis persists following such maneuvers. These representative images show a 45-year-old premenopausal woman with severe menstrual cramps and menorrhagia. Sagittal (a) and axial (b) T2-weighted images demonstrate a thickened junctional zone with multiple punctate cystic spaces (arrows) consistent with adenomyosis

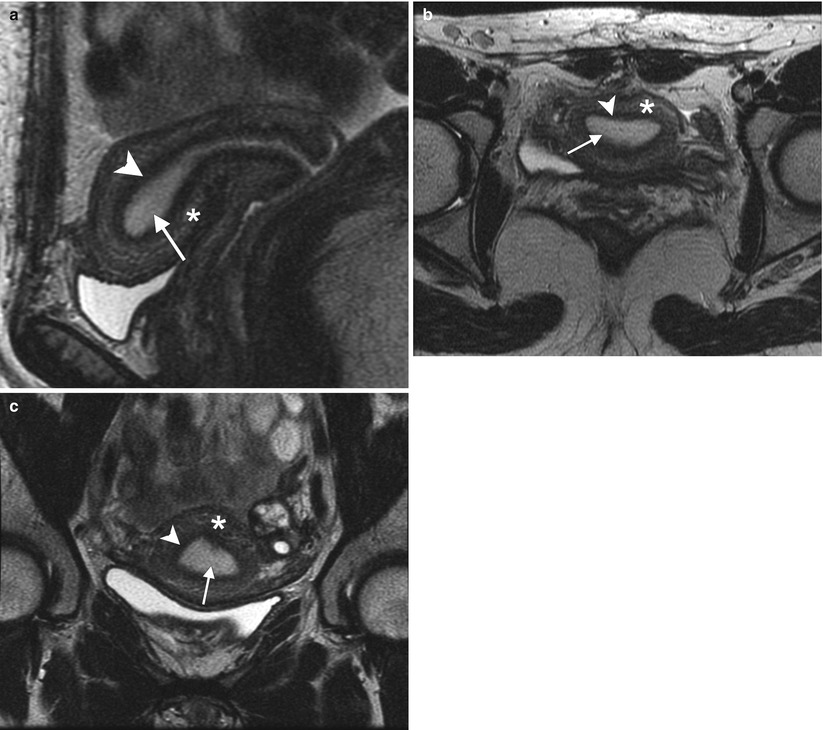

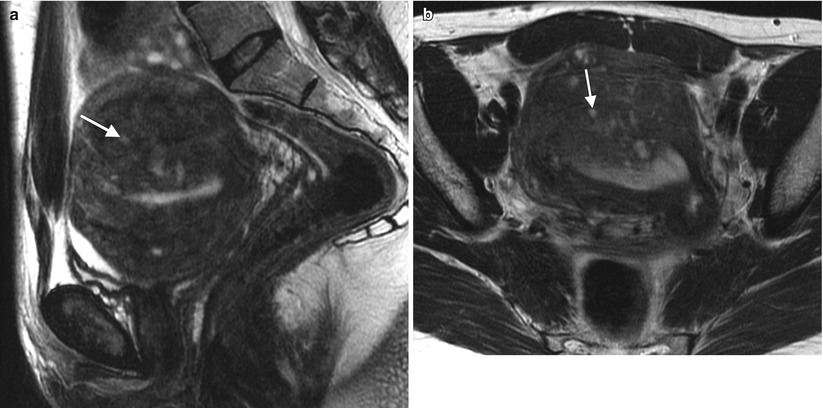

Fig. 2.4

42-year-old woman with a history of appendectomy and myomectomy for dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Sagittal (a), axial (b), and coronal (c) T2-weighted MR images demonstrate thickening of the junctional zone with small T2-hyperintense spaces (arrows) consistent with adenomyosis. There is also retraction and tethering of the soft tissues along the posterior uterine wall (arrowhead) suspicious for endometriosis. A multiloculated cystic structure (asterisks) conforming to the shape of the pelvis probably represents a peritoneal inclusion cyst

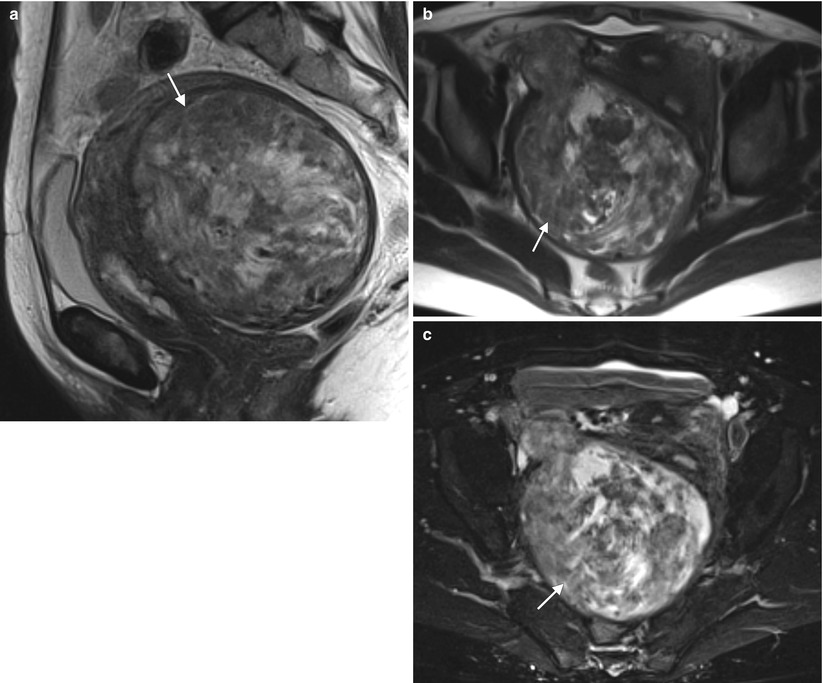

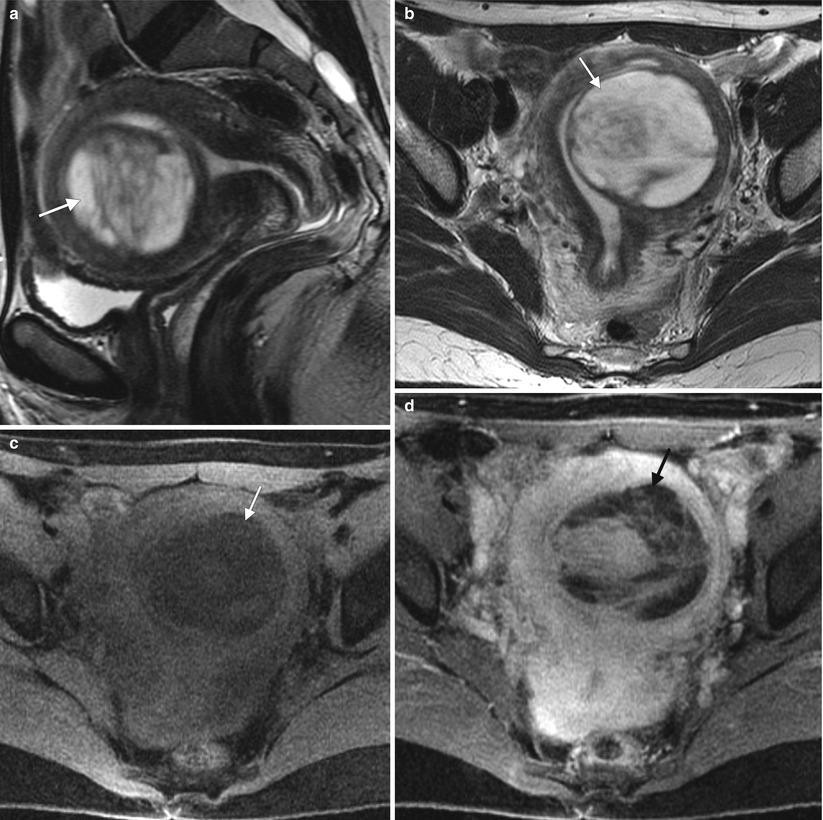

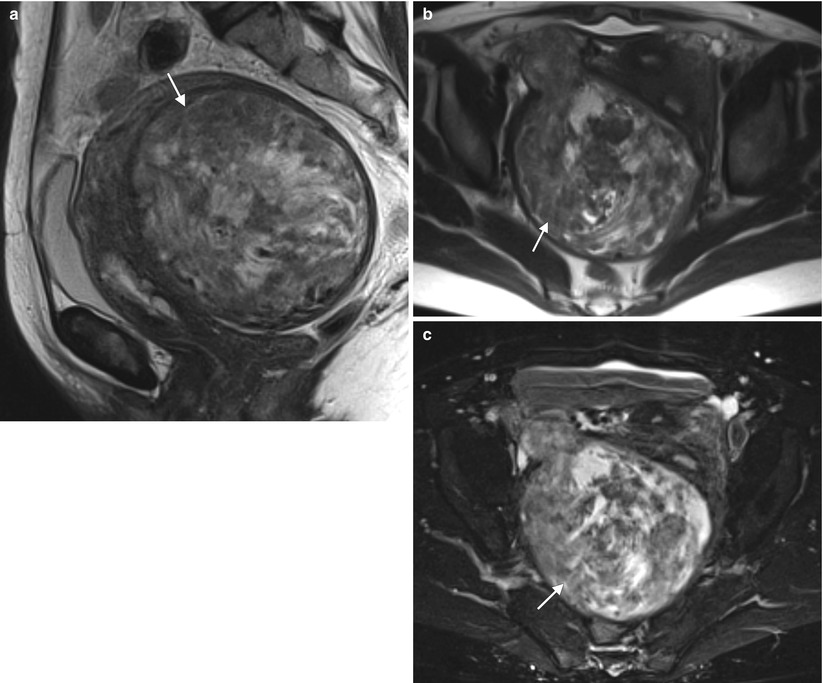

Fig. 2.5

Uterine leiomyomata (fibroids) are the most common tumors in women. They are benign masses originating from the myometrium. Symptoms vary and are related to the size and location of the tumor. The most common symptoms are menorrhagia, pelvic pressure (pain, increased urinary frequency), and infertility. These representative MR images are from a 51-year-old woman with pelvic pressure and dyspareunia. Sagittal (a) and axial (b) T2-weighted images and fat-suppressed T1-weighted images following the intravenous administration of gadolinium (c) demonstrate a heterogeneously enhancing myometrial mass (arrows). The patient underwent a hysterectomy for symptom control. Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of uterine leiomyoma

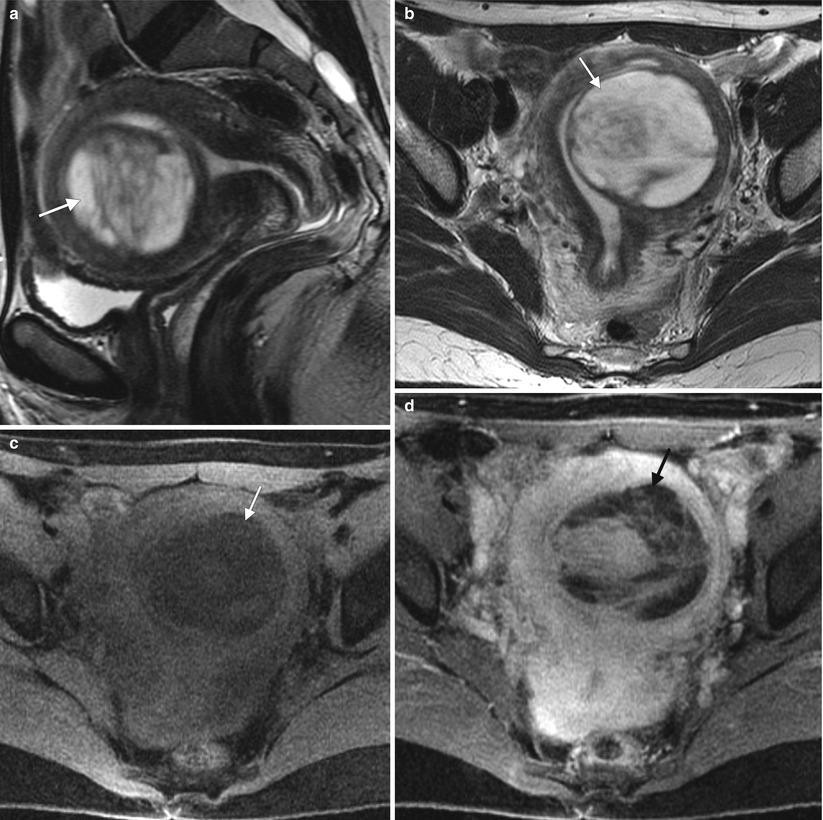

Fig. 2.6

The appearance of uterine leiomyomas is variable. These images show a 44-year-old woman with worsening menometrorrhagia over 3 years. Sagittal (a) and axial (b) T2-weighted MR images and axial fat-suppressed T1-weighted images before intravenous gadolinium (c) and after gadolinium (d) demonstrate a predominantly cystic, well-circumscribed, submucosal myometrial mass in the left uterine body (arrows) with enhancing septations. Pathology showed a degenerating leiomyoma with hydropic changes

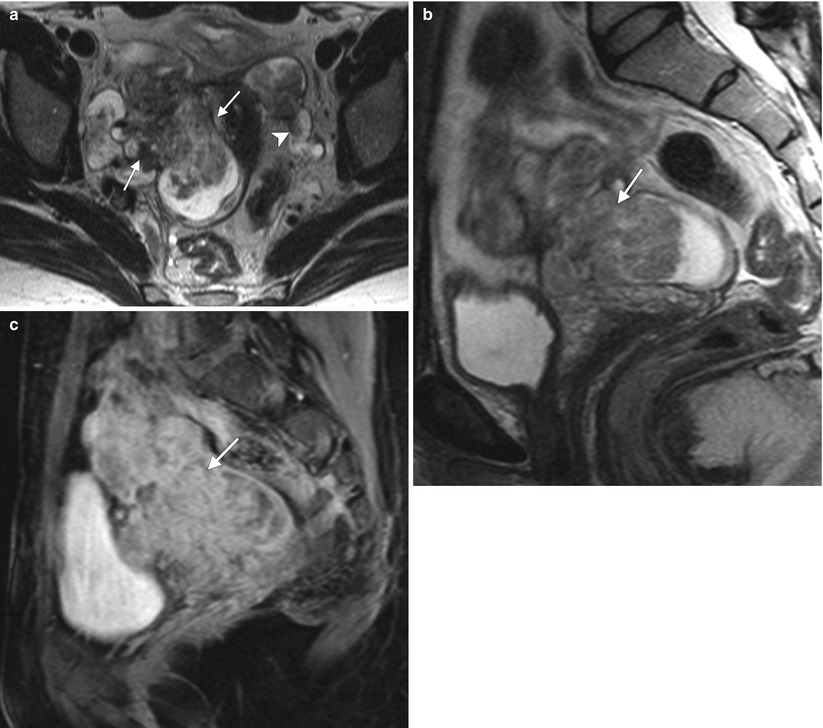

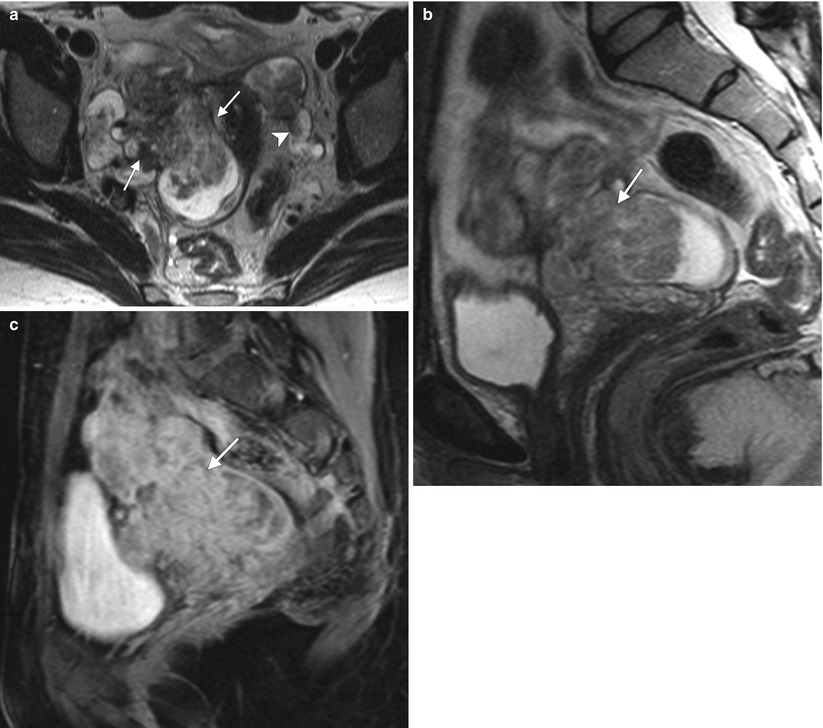

Fig. 2.7

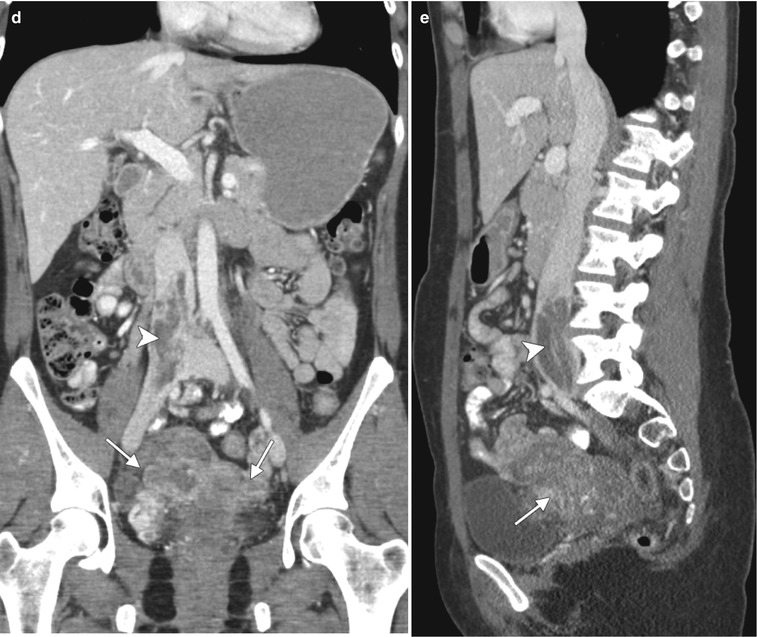

Intravenous leiomyomatosis is a rare form of uterine leiomyomatosis, usually presenting in premenopausal women. It is characterized by intravascular extension of nodular masses composed histologically of benign smooth muscle. Enhancing tumors may extend to uterine, gonadal, and iliac veins, inferior vena cava, and heart and pulmonary vasculature. This pathology is estrogen-dependent, and long-term prognosis is very good after resection. Below are representative images from a 44-year-old woman with multiple previous uterine myomectomies. Axial (a) and sagittal (b) T2-weighted MR images and a sagittal fat-suppressed, T1-weighted image following intravenous administration of gadolinium (c) demonstrate multiple, bilateral, heterogeneously enhancing masses in the pelvis (arrows). Coronal (d) and sagittal (e) contrast-enhanced CT scans demonstrate tumor extension into the right common iliac vein and inferior vena cava (arrowheads). Pathology confirmed the diagnosis of benign leiomyomata with intravenous leiomyomatosis

2.3 Malignant Uterine Pathology

The histologies of endometrial cancer (Table 2.4) are reflected in changed MRI signal characteristics (Table 2.5). The prognosis is suggested by the staging system of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) (Tables 2.6 and 2.7). Imaging findings that should be included in the radiology report are presented in Table 2.8.

Table 2.4

Endometrial cancer histologies

Histology | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 85 |

Serous adenocarcinoma | 10 |

Clear cell adenocarcinoma | <5 |

Uterine sarcomas Leiomyosarcoma Endometrial stromal sarcoma Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed müllerian tumor) | <1 |

Table 2.5

Typical MRI signal characteristics of endometrial cancer in relation to normal endometrium and normal myometrium

Imaging type | Characteristics of endometrial cancer |

|---|---|

Relative to endometrium | |

T1WI | Isointensity |

T2WI | Intermediate signal intensity |

T1WI+C | Earlier enhancement |

Relative to myometrium | |

T1WI | Variable intensity |

T2WI | Hyperintensity |

T1WI+C | Less and more delayed enhancementa |

Diffusion-weighted MRI | Hyperintensity (hypointensity on ADC map) |