Fig. 51.1

Alair® Bronchial Thermoplasty Catheter (in expanded position) and Alair RF Controller that delivers radiofrequency energy

It is important at the first bronchoscopy to survey and map the subject’s bronchial tree to enable planning of the treatment sessions (Fig. 51.2, Airway Worksheet). Any variations in anatomy and any irregularities of the bronchial tree, such as cartilaginous spurs or pigmentation or unusual vascularity, should be noted. The airways are treated systematically – starting as distal as possible under direct vision and working proximally, ensuring a continuous treatment effect to the airway wall (Fig. 51.3: BT treatment). As mentioned already, there is usually no immediate visible effect of treatment. Occasionally, a pale streak (blanching) may be seen when the electrode array is withdrawn (Fig. 51.4: blanching at BT treatment site). The array can become contaminated with mucus and epithelial debris after a number of activations. When this happens, it should be removed from the bronchoscope and cleaned with gauze soaked in sterile saline. Bleeding can occur but most often is trivial and self-limited. Preoperative management is aimed at optimizing the patient’s asthma and preventing immediate deteriorations. Thus, patients receive prednis(ol)one 50 mg or equivalent for 3 days prior, the morning of the procedure, and the day following the procedure. Pretreatment spirometry should show that the FEV1 is above 80% of maximum values and bronchodilator – albuterol or equivalent by nebulizer or inhaler – is given routinely before the procedure. Bronchospasm has been noted during treatment and can be reversed with local instillation of a dilute solution of bronchodilator if it interferes with completing the procedure. Postoperative symptoms of bronchitis – dyspnea, cough, sputum, wheeze, and chest tightness – are common and should be treated with inhaled bronchodilators such as albuterol and ipratropium along with protocol-directed 2 days of prednis(ol)one 50 mg/d. Documented infections are uncommon, but clinicians have typically had a low threshold for prescribing antibiotics to patients after bronchial thermoplasty, probably motivated by the knowledge that the bronchial epithelial layer has been breached.

Fig. 51.2

Airway Worksheet for (a) mapping of accessible airways that will be treated, note right middle lobe is not treated, and (b) logging of all complete and incomplete activations of treatment catheter

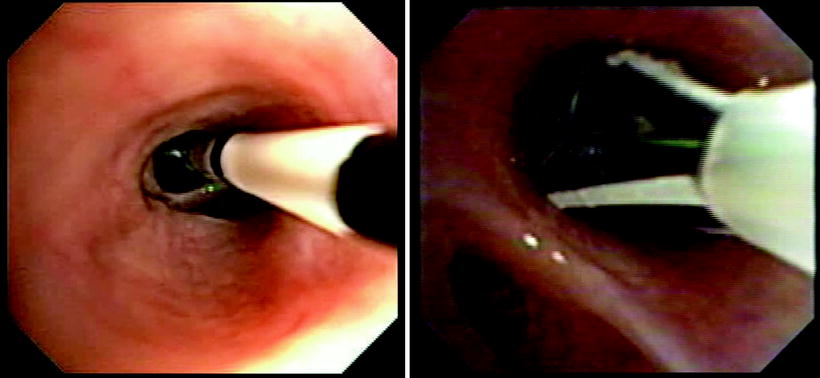

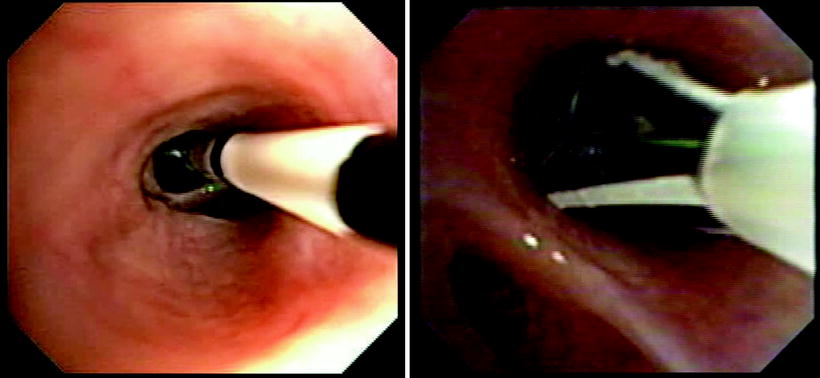

Fig. 51.3

(a) and (b) BT treatment images: Electrodes have been collapsed and catheter will be withdrawn to next treatment site. Note black marker bands on the distal catheter that are 5 mm apart to facilitate precise placement of the electrodes Catheter expanded in situ for activation. Note epithelial and or mucous accumulation on the uppermost electrode. Occasionally, when excessive, this requires removal of the treatment catheter for cleaning

Fig. 51.4

Airway wall immediate posttreatment showing pale streak (blanching) where contacted by the electrode

The first application of bronchial thermoplasty in a patient with asthma was in 2000. Since then, three randomized controlled clinical trials have been completed comprising 260 subjects, with moderate or severe asthma. The published experience documents the safety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty with follow-up out to 5 years. In 2010, both the FDA and Health Canada approved the use of bronchial thermoplasty for the treatment of severe asthma.

The initial report showed it was feasible to carry out bronchial thermoplasty in patients with mild or moderate asthma. Subsequently, three randomized, controlled trials have examined the safety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty in moderate and severe asthma: Asthma Intervention Research (AIR), Research in Severe Asthma (RISA), and the AIR2 trials. Table 51.1 provides demographic data on the subjects enrolled in these trials. The severity of asthma, as indicated by medication needs and airflow obstruction, increased across the feasibility, AIR, and RISA studies. The selection criteria for AIR2 were modified to exclude subjects with highest risk of requiring hospital admission for management of worsened asthma symptoms after treatment. Among the predictive factors for such worsening were higher requirements for oral corticosteroids and lower levels of FEV1. There was evidence of benefit following bronchial thermoplasty in all four studies, and the various outcomes are given in Table 51.2.

Table 51.1

Demographic data on subjects treated with bronchial thermoplasty

Feasibility | AIR | RISA | AIR2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

# Treated with BT | 16 | 55 | 15 | 190 |

Female (%) | 10 (63%) | 31 (56%) | 9 (60%) | 109 (57%) |

Mean age (yrs) | 39 ± 8.6 | 39 ± 11.2 | 39 ± 13 | 40 ± 11.9 |

ICS (μg BDP equiv.) | 900 ± 424 | 1,351 ± 963 | 2,333 ± 817 | 1,961 |

Criterion | N/A | ≥200 | ≥1,500 | ≥1,000 |

LABA (μg salmeterol) | 100 (5)* | 111 ± 36 | 125 ± 60 | 117 ± 34 |

Criterion | 0–100 | ≥100 | ≥100 | ≥100 |

OCS (prednisone) | 0 | 0 | 14.4 ±6.2 (8)* | 6.4 ± 2 (7)* |

Criterion | ≤ 30 mg | ≤ 10 mg | ||

Pre-BD FEV1 (%pred) | 82.3 ± 13.4 | 72.6 ± 10.4 | 62.9 ± 12.2 | 77.8 ± 15.6 |

Criterion | 60–85% | 60–85% | ≥ 50% | ≥ 60% |

Symptoms criterion | Worsening after LABA withdrawal | ≥8/14 days | ≥ 2/28 days |

Table 51.2

Outcomes indicating benefit of treatment with bronchial thermoplasty

Feasibility | AIR | RISA | AIR2 |

|---|---|---|---|

PEF | AQLQ | AQLQ | AQLQ* |

BHR | Rescue meds | Rescue meds | Time lost (work/school) |

Symptom-free days | Symptom-free days | Asthma control questionnaire | E-R visits |