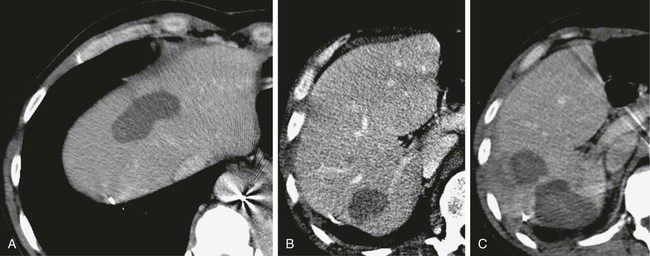

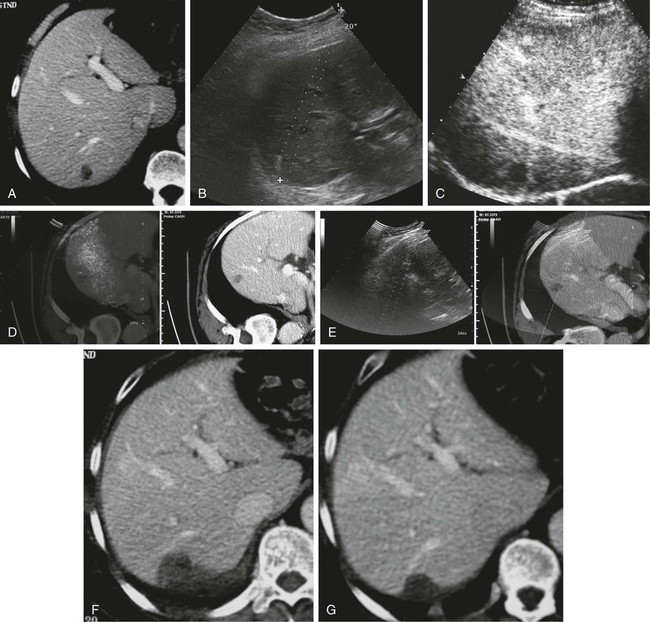

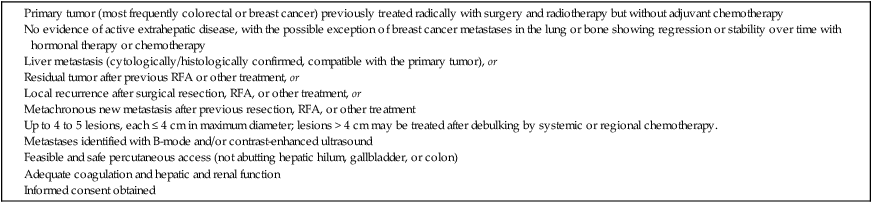

Metastatic liver disease is a very common issue in oncology practice. Currently, multiple treatment options are available, including hepatic resection, chemoembolization, intraarterial and systemic chemotherapy, cryotherapy, laser therapy, and radiofrequency ablation (RFA).1,2 Over the last few years, advances in diagnostic imaging modalities such as contrast-enhanced ultrasound, single- and multidetector helical computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with hepatobiliary and reticuloendothelial-specific contrast agents have allowed early detection and accurate quantification of liver metastatic involvement.3–10 As a result, correct selection of patients for different treatment options is usually possible. When feasible, surgical resection of hepatic metastases is the accepted standard therapeutic approach in patients with colorectal cancer and offers potential for cure in selected patients with other primary tumors.2,11–28 • Feasibility of treatment in previously resected patients and nonsurgical candidates because of the number or intrahepatic location of metastatic deposits, age, and comorbidity • Repeatability of treatment when incomplete and in the event of local recurrence or development of metachronous lesions • Combination with systemic or regional chemotherapy • Minimal invasiveness with a limited complication rate and preservation of liver function Under these conditions, RFA has to be considered a less invasive therapeutic alternative to surgery. Indications for RFA of liver metastases from other primary cancers may follow those of surgical resection. Hepatectomy for liver metastases appears to be favorable in patients with gynecologic, gastric, and testicular primary tumors, with survival rates higher than 20%; unfortunately, no definite selection criteria have been reported in the literature.22,26,27 Indications for ablation of hepatic metastases are summarized in Table 142-1. TABLE 142-1 Indications for Radiofrequency Ablation Treatment of Patients with Liver Metastases Percutaneous RFA is a minimally invasive procedure, so there are few absolute contraindications to its use. Exclusion criteria include the presence of severe coagulopathy, renal or liver failure, portal vein neoplastic thrombosis, and obstructive jaundice. Active extrahepatic disease is a contraindication to RFA, with the exception of bone or lung metastases in breast cancer patients whose disease is responding or is unchanged with systemic chemotherapy.30 Single or cluster (three needles mounted on one handle) 16-gauge internally cooled electrodes are connected to a 200-W, 480-kHz RF generator system (Radionics, Burlington, Mass.). Ablation is impedance guided with an automated pulsed-RF algorithm. The choice of electrodes is based on the size of the target nodule. For lesions smaller than 2 cm, single insertion of a 3-cm exposed-tip single electrode is sufficient. Lesions 2 to 3 cm in size can be treated by single insertion of a cluster electrode or multiple insertions of a 3-cm exposed-tip electrode. Lesions exceeding 3 cm can be treated with only one to two insertions of a cluster electrode and one to two single-electrode insertions.43,44 The applied energy is variable and usually reaches 1600 to 1800 mA for single electrodes and 1800 to 2000 mA for cluster electrodes.45,46 Each application of energy lasts 8 to 12 minutes, and total procedure time ranges from 12 to 15 minutes for small solitary lesions to 45 to 60 minutes for large or multiple ablations.47–49 B-mode and color/power Doppler ultrasound is unreliable in assessing the size and completeness of induced coagulation necrosis at the end of the application of energy. Furthermore, additional repositioning of the electrode is usually made difficult by the hyperechogenic “cloud” appearing around the distal probe. Therefore, we routinely perform contrast-enhanced ultrasound at the presumed end of the treatment session to enable rapid assessment of the extent of tissue ablation and detect viable tumor requiring additional immediate treatment.50 Keeping a “safety peripheral margin,” as in surgical treatment of tumor lesions, is crucial in the long-term outcome. A minimum margin of 0.5 cm is necessary; enlarging the target area by a 1-cm margin when feasible is highly recommended (Fig. 142-1). Real-time ultrasound/CT fusion imaging technology allows targeting of lesions visible only with CT (Fig. 142-2), real-time calculation of the volume to be treated before treatment is undertaken, and guidance of further electrode insertion into the same target, which is often completely obscured for sonography by the gas formed during RFA.

Energy-Based Ablation of Other Liver Lesions

Indications

Colorectal Metastases

Noncolorectal Metastases

Contraindications

Equipment

Technique

Technical Aspects

Radiology Key

Fastest Radiology Insight Engine