Epilepsy Imaged with PET and SPECT

Alfred Buck

Heinz-Gregor Wieser

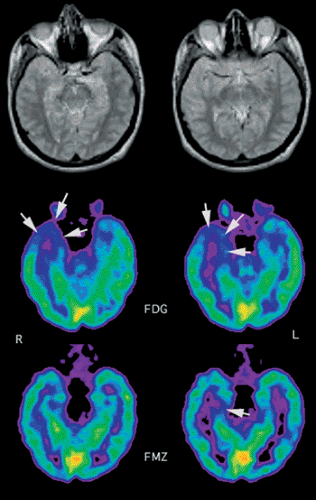

Positron emission tomography (PET) scans are indicated in the presurgical evaluation of epilepsy patients. Most of these patients suffer from temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), where the major pathology is found in the medial temporal lobe. One of the operations performed to cure such epilepsy is selective amygdalohippocampectomy. A prerequisite for deciding on such surgery is that the disease is unilateral, since a bilateral operation would lead to intolerable neuropsychological deficits. The most commonly used tracer in PET epilepsy imaging is fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), and the typical finding in TLE is illustrated in Figure 25.1. The reduction of FDG uptake is not restricted to the medial temporal lobe but extends to the lateral temporal lobe. The important information FDG PET can provide is that the pathology is unilateral. There are indications that carbon 11 [11C]flumazenil, which binds to the benzodiazepine receptors, shows the pathology in a somewhat better circumscribed way. This is illustrated in the bottom panel of Figure 25.1. However, [11C]flumazenil requires an on-site cyclotron, which renders the tracer less available.

Another important application of PET in epilepsy concerns ictal studies. These are usually done with perfusion tracers, and the tracers need to be injected within minutes of the onset of a seizure. This puts a challenging demand on the imaging infrastructure. Most of these studies are performed with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and a technetium 99m (99mTc)–labeled flow tracer. Due to the relatively long half-life of 99mTc, one can prepare the tracer and wait for a seizure to occur. After the seizure and the concomitant tracer injection, the patient can be stabilized and images acquired hours after injection. If seizures can be triggered reproducibly, ictal studies can also be performed with PET. An example is shown in Figure 25.2.

Introduction

Epilepsy represents a considerable health care problem, and in the United States the prevalence is 500 to 800 cases per 100,000. The classification of epilepsies, seizures, and epileptic syndromes uses these categories: primary, generalized, and partial. It is the partial epilepsies where functional neuroimaging is of special interest. Partial seizures originate from one focus. The epileptic discharge may remain localized or may spread over the whole brain. In the latter case, one talks of “secondary generalization.” If partial seizures involve consciousness, they are referred to as “complex partial seizures.” In general, these originate in the medial temporal lobe. Although most epileptic patients are adequately treated with medication, a considerable number are medically intractable. A major subgroup of these patients suffer from temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), which is commonly associated with hippocampal sclerosis. Surgical treatment in these cases has proven to be an effective means of eliminating seizures. There exist various surgical strategies. The standard procedure initially consisted of removing the anterior two thirds of the affected temporal lobe, so-called Falconer’s en bloc anterior temporal lobe resection. In Zurich, the standard operation since 1975 has been selective amygdalohippocampectomy, a procedure pioneered by Wieser and Yasargil (1). For extratemporal refractory epilepsy, surgical therapy is less often performed, although this is changing with improved methods for presurgical evaluation. In general, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging has proven to be useful in candidates for epilepsy surgery.

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Preoperative Evaluation

The aim of preoperative evaluation in temporal lobe epilepsy is to maximize the chances for the patient to be free of postsurgical seizures (or at least have a substantial reduction in seizure frequency) and minimize postsurgical deficits. A prerequisite for surgery is that the seizures always originate from a stable focus. Patients displaying bilateral disease must be excluded from operative treatment since the neuropsychological deficits following a bilateral operation would be prohibitive. The preoperative workup of patients with TLE differs somewhat among centers. At our institution, it includes noninvasive as well as invasive electroencephalographic recording of interictal and ictal events (EEG), long-term video monitoring, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and FDG PET. All these modalities yield complementary information.

FDG PET

The typical interictal finding in TLE is reduced FDG uptake in the affected temporal lobe. The area of hypometabolism usually extends beyond the medial temporal lobe and often includes the lateral temporal cortex, as is illustrated in Figures 25.1, 25.2, 25.3, 25.4 and 25.5. A likely reason for this phenomenon is deafferentation of the cortex functionally connected with the epileptogenic focus. Besides the abnormality in the medial temporal lobe, hypometabolic regions in TLE are also reported: the thalamus, the basal ganglia, and parts of the frontal lobe (2). These examples illustrate that FDG PET is not suitable for localizing the seizure onset zone per se. The important PET information is the lateralization and the exclusion of a pathology on the contralateral side. The incidence of an ipsilateral temporal lobe hypometabolism in patients with TLE is in the range of 60% to 90% (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10).

Flumazenil PET

Flumazenil (FMZ) is a benzodiazepine receptor antagonist. Labeled with carbon 11 (11C), it is an excellent PET marker for cerebral benzodiazepine receptor density. Since the receptors are located on the neurons, reduction in receptor density may indicate neuronal loss, as is typical in a sclerotic region. Examples of FMZ PET images in patients with TLE are shown in Figures 25.1, 25.2, 25.3, 25.4 and 25.5. Whereas glucose metabolism is depressed well beyond the sclerotic medial temporal lobe, FMZ demonstrates a circumscribed defect limited to the affected medial temporal lobe. An interesting case is shown in Figure 25.4. This patient was not seizure free following selective amygdalohippocampectomy. Besides a lack of uptake in the operated area, there is also reduced FDG uptake PET in almost the whole lateral temporal lobe. Although extended reduction in FDG uptake is typical in TLE, the degree and area of reduction in this patient exceeded the usual pattern. The question therefore arose whether there might be neuronal damage in the lateral temporal lobe. Structural damage in this area was excluded on MRI (Fig. 25.4B). The normal FMZ uptake in the lateral temporal lobe clearly demonstrates neuronal integrity. That reduction of FMZ uptake is restricted to the abnormal tissue, was demonstrated in several studies (11,12) and confirmed using the more objective method of statistical parametric mapping (13). In another study, it was shown that by correcting for resolution effects, the sensitivity for detection of unilateral hippocampal sclerosis could be increased to 100% (14). Abnormalities on the contralateral side were present in 30% of cases.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

The main rationale for MRI in epilepsy patients is to identify or exclude underlying pathologies such as tumors,

vascular lesions, and migrational disorders. In TLE, the most common pathology is hippocampal sclerosis, which resisted reliable evaluation with MRI until the early 1990s. This has changed with the advance of MRI technology. There exist qualitative and quantitative approaches to assess hippocampal sclerosis; the latter are more accurate and measure the hippocampal volume. In a study with 41 patients, it was shown that hippocampal volume ratios yielded the correct lateralization of the seizure focus in 76% of cases (15). Although useful, the technique of hippocampal volumetry is rather laborious and therefore not suitable in a clinical setting. Nevertheless, new methods like voxel-based morphometry seem to ameliorate subjective bias (16,17). In addition MRI studies revealed that other structures, such as the parahippocampal area, the entorhinal cortex, and the thalamus, seem to be involved in temporal lobe epilepsy (18,19).

vascular lesions, and migrational disorders. In TLE, the most common pathology is hippocampal sclerosis, which resisted reliable evaluation with MRI until the early 1990s. This has changed with the advance of MRI technology. There exist qualitative and quantitative approaches to assess hippocampal sclerosis; the latter are more accurate and measure the hippocampal volume. In a study with 41 patients, it was shown that hippocampal volume ratios yielded the correct lateralization of the seizure focus in 76% of cases (15). Although useful, the technique of hippocampal volumetry is rather laborious and therefore not suitable in a clinical setting. Nevertheless, new methods like voxel-based morphometry seem to ameliorate subjective bias (16,17). In addition MRI studies revealed that other structures, such as the parahippocampal area, the entorhinal cortex, and the thalamus, seem to be involved in temporal lobe epilepsy (18,19).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree