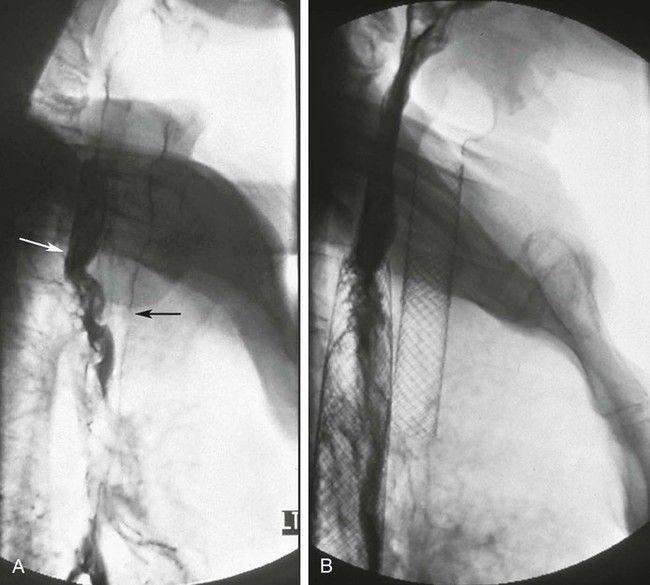

Chapter 129 Tarun Sabharwal, Stavros Spiliopoulos and Andreas Adam Dysphagia is the most common symptom associated with esophageal strictures. Patients typically complain of solid-food dysphagia that may progress over time to include liquids. If patients present initially with solid and liquid dysphagia, a motility disorder rather than an anatomic abnormality should be suspected. Patients may also report symptoms of regurgitation or aspiration, chest pain, abdominal pain, or weight loss. Analysis of the patient’s symptoms can guide the clinician to the correct diagnosis in 80% of dysphagia cases.1 Esophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of death from cancer worldwide.2,3 Because patients may not experience dysphagia until the luminal diameter has been reduced by 50%, cancer of the esophagus is generally associated with late presentation and poor prognosis. The overall 5-year survival rate is less than 10%, and fewer than 50% of patients are suitable for resection at presentation.4,5 The aims of palliation are maintenance of oral intake, relief of pain, elimination of reflux and regurgitation, prevention of aspiration, and minimization of hospital stay.6–8 Current palliative treatment options include thermal ablation,9 photodynamic therapy,10 radiotherapy,11 chemotherapy,12 chemical injection,13 argon beam or bipolar electrocoagulation,14 enteral feeding (nasogastric tube/percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy),15 and intubation using either self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) or semirigid plastic tubes.7,8 Esophageal prostheses have been in use for over a century. Different tubes of the pulsion and traction variety have been described. The earliest device, made of decalcified ivory, was designed by Leroy d’Etiolles in 1845. The first metal esophageal prosthesis was introduced by Charters J. Symonds in 1885.16 Modern esophageal stenting utilizes either rigid plastic tubes or SEMS. Benign strictures of the esophagus occur as the result of collagen deposition and fibrous tissue formation stimulated by esophageal injury. Peptic strictures, caused by esophageal exposure to gastric acid, account for 70% to 75% of benign esophageal strictures.17,18 Other common causes of benign strictures include Schatzki ring, ingestion of corrosive agents (including certain medications), external-beam radiation therapy, sclerotherapy, photodynamic therapy, reaction to a foreign body, infectious esophagitis, and surgical trauma.19,20 • Grade I: shelf strictures involving a short segment but not circumferential • Grade II: annular strictures less than 1 cm in length • Grade III: dense annular strictures less than 1 cm long extended through all layers • Grade IV: tubular strictures with periesophageal adhesions The following symptoms and signs characterize achalasia: • Dysphagia: the most common presenting symptom; dysphagia for solids is more common than for liquids. • Regurgitation: Many patients with achalasia experience spontaneous regurgitation of undigested food from the esophagus. • Chest pain: 25% to 50% of patients with achalasia report episodes of retrosternal chest pain that are frequently induced by eating. Patients with long-standing achalasia are at increased risk for esophageal cancer. Treatment is directed toward symptomatic relief of the disorder, which is achieved by disrupting the muscle fibers of the LES, usually by using surgical cardiomyotomy or balloon dilation.21 The therapeutic results after either technique are broadly similar,4 but balloon dilation has several advantages: thoracic or abdominal surgery is avoided, the average hospital stay is shorter, and there is a lower incidence of subsequent esophageal reflux.22 Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a very rare skin fragility disorder characterized by blister formation following minor mechanical trauma. The clinical subset varies from only mild skin reactions to severe mutilating deformities such as pseudosyndactyly and fatal forms, depending on the genotypic subtype of the disease. In severe types, gastrointestinal, urologic, and corneal abnormalities have been also noted.23 In general, two major categories are recognized: inherited (IEB) and acquisita (EBA). The inherited type is more common and can be divided into four principal types: EB simplex, dystrophic EB, junctional EB, and Kindler syndrome.24,25 It is calculated that IEB affects 1 to 3 births in every 100,000 live births; nearly 5000 patients in the United Kingdom suffer from the disease.26 EBA is an autoimmune primary blistering disease associated with immunoglobulin G (Ig) autoantibodies against type VII collagen, the basal membrane zone (BMZ) of the skin and the malpighian mucosa. Collagen VII is a major component of esophageal epithelium, so high-grade esophageal strictures resulting in severe dysphagia and malnutrition are noted in various EB subtypes. Esophageal involvement is more frequent in the recessive dystrophic EB subtype; almost 70% of these patients will develop at least one esophageal stricture by the age of 25.27 Diagnosis of esophageal involvement in patients suffering from EB is based on clinical symptomatology (various grades of dysphagia) and can be radiologically documented with a barium esophagogram. Typical EB stenotic lesions are present in the upper esophageal segments at the level of C5-C7 and can be either smooth, usually short stenotic lesions or weblike, tight, focal, fibrotic strictures.28 High strictures are more frequent because of the physiologic narrowing of the upper part of the esophageal canal, which is therefore more exposed to mechanical trauma during deglutition; however, stenosis of the lower parts of the esophagus are also possible. A differential diagnosis of a true weblike stricture and the presence of transient indentation of the anterior cricopharyngeal wall should be obtained. Treatment options for the esophageal stenosis include conservative medical management in the acute phase using steroids and phenytoin, esophageal dilation, and surgical replacement. With the latter being reserved only for few selected cases, fluoroscopically-guided or endoscopic balloon dilatations are the most common management methods of dysphagia in EB. However, fluoroscopically guided dilatation offers a less traumatic approach because the lesion is crossed using floppy guidewires, in contrast to endoscopic dilatation, which may cause a significant degree of pharyngoesophageal trauma while advancing the endoscope. In addition, the procedure can be performed under heavy sedation without use of an artificial airway when intubation is impossible or not deemed necessary by the anesthesiologist. In cases where a gastrostomy tube is in place, the procedure can also be performed retrograde via the preexisting tube. Use of balloons ranging from 18 to 26 mm in diameter has been reported to be safe and effective.29 The main indications for esophageal stenting in malignant disease are: • Intrinsic esophageal obstruction • Tracheoesophageal fistula. Spontaneous malignant fistulas between the esophagus and major airways occur as a result of local tumor invasion from the esophagus or tracheobronchial tree (Fig. 129-1) or may be secondary to surgery or esophageal stent placement. Esophageal leaks or perforations are usually iatrogenic following esophageal dilation or surgery, but may also be caused by local tumor invasion. Leaks and fistulas in benign disease should not be stented because leakage occurs around the stent. In many such cases, there is spontaneous healing. However, without definitive treatment, malignant lesions will not heal, and most patients would die of malnutrition and thoracic sepsis within weeks. Until recently, therapy for malignant leaks and fistulas has been unsatisfactory. Attempted surgical repair has a high morbidity and mortality. Parenteral nutrition or feeding via a gastrostomy were often used, but continuing leakage of esophageal contents resulted in mediastinitis in many patients. Attempts to seal the esophageal defect with plastic stents were usually ineffective. Covered self-expanding metallic stents are the treatment of first choice in patients with malignant leaks and fistulas, because the metallic stent expands to the diameter of the esophagus, and the covering material seals the defect. • Extrinsic esophageal compression by primary or secondary mediastinal tumors • Esophageal perforation, usually iatrogenic, from direct endoscopic trauma or following stricture dilation • Symptomatic gastroesophageal anastomotic leaks • Radiotherapy during the previous 6 weeks, which is associated with increased hemorrhage and perforation rates if stents are inserted • Malignant obstruction of the gastric outlet or small bowel • Strictures above the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle • Severe tracheal compression that would be made worse by esophageal intubation

Esophageal Intervention in Malignant and Benign Esophageal Disease

Indications

Benign Esophageal Strictures

Corrosive Strictures

Achalasia

Clinical Presentation

Treatment

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Diagnosis

Treatment

Malignant Esophageal Strictures

Contraindications