The epidemiology and clinical management of esophageal carcinomas are changing, and clinical imagers are required to understand both the imaging appearances of common cancers and the pathologic diagnoses that drive management. Rare esophageal malignancies and benign esophageal neoplasms have distinct imaging features that may suggest a diagnosis and guide the next steps clinically. Furthermore, these imaging features have a basis in pathology, and this article focuses on the relationship between pathologic features and imaging manifestations that will help an informed imager maintain clinical relevance.

Key points

- •

The radiologic-pathologic correlation of esophageal neoplasms is an important skill for clinical imagers, informing both diagnosis and anticipated clinical management.

- •

The epidemiology and management of esophageal carcinomas are changing, and clinical imagers will have increased specificity and clinical relevancy if they can put these tumors into an appropriate clinical context.

- •

Rare malignancies and benign esophageal neoplasms have distinct imaging appearances because of their underlying histology.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the seventh most common cancer worldwide, with more than 572,000 cases, resulting in more than 508,000 deaths in 2018. In the United States in 2020, the American Cancer Society estimates there will be more than 18,400 new cases of esophageal cancer diagnosed, resulting in more than 16,000 deaths. Although esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) accounts for approximately 90% of cases worldwide, largely attributable to cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption, there has been a shift toward esophageal adenocarcinomas (EACs), especially in North America and Europe. In the United States, the prevalence of EAC has now surpassed that of ESCC, as the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and prevalence of obesity have increased.

At autopsy, benign tumors represent only 20% of esophageal neoplasms. Most are small lesions that cause no symptoms; however, dysphagia, bleeding, or other symptoms can occur, in which case endoscopic or surgical removal may be necessary. Of these, leiomyomas occur most frequently, accounting for more than 50% of all benign neoplasms, and occur nearly twice as often in men. , Tumor-like conditions, such as fibrovascular polyps, also occur in the esophagus and have a distinct clinical presentation and imaging appearance.

This article examines the imaging appearances of esophageal neoplasms, with an emphasis on the pathologic basis of those manifestations. Although accurate diagnosis of esophageal neoplasms typically begins with imaging, the pathologic findings play a key role in determining treatment and prognosis, and imagers should be equipped to discuss this radiologic-pathologic relationship as part of the care team.

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

Clinical Features

ESCC is a malignant epithelial tumor of the esophagus with squamous cell differentiation. The etiology of ESCC is multifactorial and has been shown to be strongly population-dependent. In the United States, the 2 most significant risk factors are tobacco use and excessive alcohol consumption, which together have a synergistic effect. Certain medical conditions, including Fanconi anemia, lye strictures, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, Zenker diverticulum, tylosis, achalasia, and prior therapeutic radiation to the chest, also place patients at higher risk for ESCC.

ESCC has a male predominance and is 5 times more common among African Americans than whites. The median age of presentation is within the seventh decade of life. Patients tend to be asymptomatic early in the disease, but, by the time of presentation, 80% to 90% of patients endorse progressive dysphagia (Hofstetter, 2019). Weight loss results from decreased oral intake and is associated with worse clinical outcomes. Other symptoms include odynophagia, emesis, cough, chest pain, and anemia.

Local tumor extension can manifest as hoarseness secondary to recurrent laryngeal nerve injury or, occasionally, as an esophagorespiratory fistula. Rarely, ESCC patients may demonstrate hypercalcemia secondary to tumoral production of parathyroid hormone–related protein. Distant metastases may be seen in up to 20% to 30% of patients at presentation. The most common locations of distant metastases include the lungs, liver, bones, and brain. Synchronous or metachronous head/neck SCCs are present in 3% to 10% of patients, which are thought to be related to smoking.

Pathologic Reatures

ESCC develops through a stepwise progression from histologically normal squamous mucosa to squamous cell dysplasia and finally to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous cell dysplasia (or intraepithelial neoplasia) is considered a histologic precursor and is characterized by cellular atypia, abnormal differentiation, and disorganized architecture. , Not only is intraepithelial neoplasia found adjacent to invasive ESCC in a majority of cases, but also its presence at biopsy places a patient at significantly increased risk for the future development of ESCC.

With neoplastic cell invasion through the basement membrane, a lesion is considered invasive ESCC. Defining tumor depth of invasion on a microscopic level is an important prognostic factor. As tumor invasion becomes progressively deeper, there is a concomitant increase in frequency of lymph node metastases. The frequency of lymph node metastases nearly doubles as a tumor invades into each progressively deeper one-third of the submucosal layer.

Imaging Features

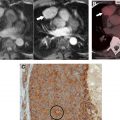

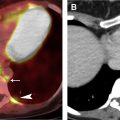

Multimodality imaging plays a crucial role in the clinical staging of ESCC and treatment planning ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). Clinical staging is defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system using TNM subclassifications, which is currently in its eighth edition, for esophageal and esophagogastric carcinomas. Tumor location no longer is considered a factor in determining clinical staging but should be noted, because it determines the expected location of potential regional lymph node metastases and can have an impact on surgical approach. With imaging and endoscopy, the tumor’s epicenter rather than its upper edge is described. A majority of ESCCs are located within the mid-esophagus followed by the lower esophagus.

Traditionally, barium esophagography was considered part of the work-up for esophageal carcinomas. This examination no longer is considered routine but occasionally may be performed prior to endoscopies, acting as a road map. On double-contrast esophagrams, superficial tumors appear as small protruded lesions, manifesting as plaque-like lesions with or without central ulcers, sessile polyps, and/or focal irregularities of the esophageal wall. The more commonly seen advanced tumors are infiltrating, manifesting as irregular luminal narrowing with nodularity and/or ulceration and abrupt shouldering margins. , Morphology on barium studies typically matches those on endoscopy and pathology, and, although not specific, occasionally can suggest depth of invasion and risk of lymph node metastases.

Computed tomography (CT) is an important modality in the work-up of esophageal cancers. Primary tumors are detected on CT through evaluation of esophageal wall thickness, which is considered abnormal if greater than 5 mm. ESCC typically manifests as esophageal wall thickening or a mass that causes luminal obstruction if advanced. Earlier tumors may be difficult to detect but occasionally can present as asymmetric thickening of the esophageal wall. Beyond displaying the primary tumor, CT is unable to illuminate the depth of tumor invasion, particularly in early cancers, significantly limiting its usefulness in T staging. Despite this limitation, CT does have some utility in the assessment of T4 lesions. In general, local invasion is suggested with a loss of fat planes between the tumor and adjacent structures in the mediastinum. For example, if the tumor and aorta have an interface greater than 90°, this can suggest aortic invasion. CT has a moderate sensitivity for detection of locoregional disease and even higher for distant metastases. , CT evaluation of nodal disease is based primarily on size criteria, which characterizes a lymph node as pathologic if it measures greater than 1 cm in short-axis in the presence of known esophageal malignancy. This is, however, neither specific or sensitive and is less accurate than endoscopic ultrasound (EUS).

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET/CT can delineate the location of the primary tumor, because most ESCCs are FDG-avid. Similar to CT, however, this imaging modality has little role in T staging, because it is unable to differentiate among the different layers of the esophageal wall. It can less commonly delineate locoregional disease but is inferior to EUS. FDG PET/CT’s true importance lies in its ability to detect distant metastases and recurrence. It has been shown to be far superior in the detection of distant metastases compared with CT and EUS. Additionally, FDG PET/CT is critical in evaluating treatment response following neoadjuvant chemoradiation, which has been shown to provide prognostic information regarding survival. , For example, patients whose FDG PET/CT scans demonstrated maximum standardized uptake values that decreased by greater than 50% compared with their pretreatment scans had a longer overall survival and decreased risk of death following surgery.

EUS currently is the most accurate tool available in determining depth of tumor invasion (T stage) because it can directly visualize all of the layers of the esophageal wall. ESCC presents as a hypoechoic mass that, depending on its depth of invasion, obscures 1 or more of the 5 alternating echogenic and hypoechoic lines that represent the normal layers of the esophageal wall. EUS also is the most accurate means for determining N staging, with a reported accuracy rate of 72% to 80% (compared with the 46%–58% accuracy of CT). , In contrast, EUS has limited value in the assessment of distant metastases and generally is not recommended for treatment response assessment.

Management

Because a majority of patients present in advanced stages of the disease, the prognosis for ESCC is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 17%. A multidisciplinary approach is considered the mainstay of treatment of ESCC. Esophagectomy alone is recommended for T1-T2 cancers or patients who cannot tolerate combined modality therapy. Endoscopic techniques, including endoscopic mucosal resection and ablation therapy, can be considered as esophageal-preserving alternatives to surgery in patients with T1a lesions. Patients with T1b lesions generally are not considered candidates for these approaches due to their increased risk of lymph node involvement. That said, more recently, an increasing number of select patients with superficial submucosal invasion T1b lesions with additional favorable features are being treated with endoscopic mucosal resection with good outcomes.

For locally advanced cancers, multimodality therapy is the standard of care and consists of neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by restaging and consideration for esophagectomy. Adjuvant chemoradiation may benefit some patients with ESCC, particularly if a patient has not previously received neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

Definitive chemoradiation or, less preferably, radiation therapy without subsequent surgery is a possibility for patients who either opt out of or are not candidates for surgery; this approach has been used increasingly to treat ESCC in the cervical and proximal esophagus. Compared with patients who subsequently underwent esophagectomy, those who solely receive definitive chemoradiation have worse locoregional control, but overall survival does not appear to be significantly different between these groups. A palliative approach generally is pursued for patients with T4b tumors or distant metastases, which can include palliative chemoradiation, surgical debulking, and/or esophageal stenting for better symptom control.

Esophageal adenocarcinoma

Clinical Features

EAC is a malignant epithelial tumor of the esophagus with glandular or mucinous differentiation that typically arises within Barrett esophagus in the lower one-third of the esophagus. It is strongly tied to chronic GERD and the development of Barrett esophagus. The latter is diagnosed in 1% to 2% of the general population and its annual incidence of malignant transformation to EAC is reported to be 0.2% to 0.5% per year. , Other risk factors in the development of EAC include tobacco smoking and obesity.

Similar to ESCC, EAC demonstrates a slight male predominance and a mean age at presentation within the seventh decade of life. Unlike ESCC, EAC is more common among whites. The clinical presentation generally mirrors that for ESCC. It is, however, more common for patients with EAC to endorse chronic reflux symptoms. Furthermore, patients with EAC are more likely to demonstrate intra-abdominal metastases in contrast to ESCC, which more commonly metastasizes to intrathoracic or cervical sites. The prognosis for EAC is variable but generally tends to be poor, albeit slightly more favorable than that for ESCC.

Pathologic Features

Grossly, EACs can be described using the same classification system as ESCCs. EAC lesions tend to be infiltrating, polypoid, or ulcerative. If EAC has developed in a background of Barrett esophagus, this can be visualized on endoscopy as reddish mucosa in the distal esophagus compared with the pale grayish color of the normal esophageal squamous cell epithelium. ,

EAC develops through a multistep pathway characterized by a Barrett metaplasia–dysplasia–adenocarcinoma sequence. Less commonly, it develops within heterotopic gastric mucosa or from esophageal mucosal/submucosal glands. Although other types of columnar metaplasia are possible, it is the presence of intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells that specifically defines Barrett esophagus in the United States.

Similar to ESCC, invasive EAC is defined as the invasion of neoplastic cells through the basement membrane. Microscopically, invasive EAC is characterized by mucinous or gland differentiation. The percentage of glandular formation in the carcinoma forms the basis for EAC grading.

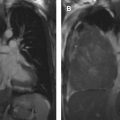

Imaging Features

Similar to ESCC, multimodality imaging is central to the work-up for EAC ( Fig. 3 ). EACs appear similar to ESCCs on each of the imaging modalities. One feature that can suggest one lesion over the other is its location. EAC tends to occur mainly in the distal esophagus and, unlike ESCC, it has a strong predilection for invading the gastric cardia and/or fundus. Another difference is that EACs are more likely to have adjacent strictures secondary to the presence of chronic GERD, a finding that commonly is appreciated on barium esophagrams. Patients with EACs also are more likely to have intra-abdominal metastases, as discussed previously, which tend to be well visualized on FDG PET/CT and CT. Finally, EACs generally are less FDG-avid than ESCCs and tend to be more heterogeneous in their avidity. As was reported for gastric adenocarcinomas, EACs that are poorly differentiated or demonstrate diffuse-type, signet cell, or mucinous patterns tend to be on average less FDG-avid (Stahl and colleagues, 2008). In general, however, imaging cannot reliably differentiate EAC from ESCC.