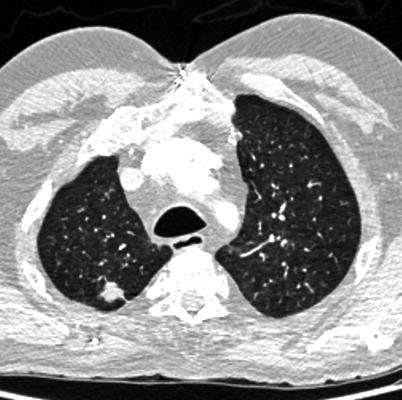

Fig. 18.1

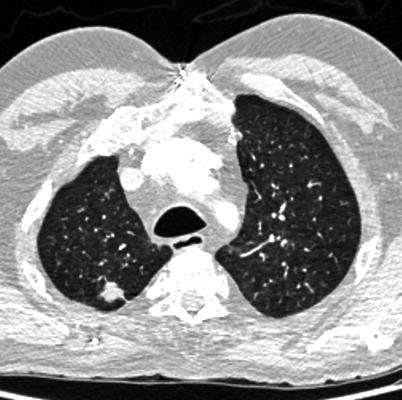

A 72-year-old male, with a 40 pack-year smoking history. MDCT demonstrates severe centrilobular emphysema on the lung algorithm image

Evaluation of Bony Structures

Incidentally discovered thoracolumbar vertebral compression fractures are common, and often underreported, seen in 9–35 % of MDCT evaluations, with the incidence largely related to patient age and gender (Fig. 18.2) [15, 16]. It is valuable to assess the thoracolumbar spine using a bone reconstruction algorithm in the sagittal plane to avoid missing mild or even moderate compression fractures. Seemingly innocuous, such fractures have shown an association with significant morbidity and mortality [17]. The risk of subsequent vertebral and hip fractures rises significantly [18]. Correlation with bone mineral density is recommended in this setting. The institution of pharmacotherapy, to combat osteoporosis, or vertebroplasty, in the setting of ongoing pain, is a possible treatment option [15].

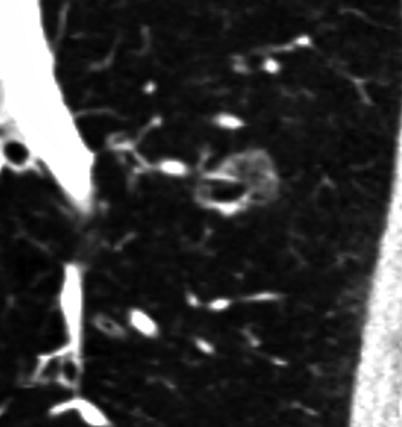

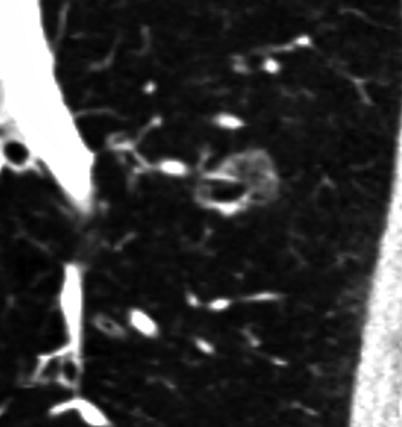

Fig. 18.2

A 60-year-old male patient with a 1.3 cm spiculated right upper lobe lung lesion. This lesion was subsequently biopsied, with pathology in keeping with non-small cell lung cancer (adenocarcinoma)

Pulmonary Evaluation

Evaluation of the lung parenchyma can be divided into assessment of diffuse pathologies such as emphysema or pulmonary fibrosis and detection of focal lesions such as nodules or masses.

Diffuse pathologies such as emphysema increase in incidence with aging (Fig. 18.3). It is estimated that nearly one-third of smokers will develop emphysema by the age of 75, as determined by pulmonary function testing [19]. MDCT is felt to be a more sensitive tool in detection of underlying COPD when compared to standard pulmonary function testing, although it does remain relatively insensitive to early stages of disease [20].

Fig. 18.3

A 79-year-old male, with a 1.6 cm subsolid nodule in the left lower lobe, demonstrating ground glass superiorly and a small solid component inferiorly

Pulmonary nodules are a common finding on CT examinations. Depending on the patient population evaluated, they may be detected in up to 51 % of MDCT examinations which image the entire chest [21]. Unlike many incidentally detected findings, well-established guidelines for follow-up of solid pulmonary nodules do exist [22].

There are a number of features which would indicate a nodule is definitively benign. The first of these is the presence of fat attenuation. If a solid lung lesion demonstrates attenuation of −40 to −120 HU, and no history of a primary fat-containing malignancy is present, such a lesion can be considered to be a hamartoma and will not require follow-up imaging [23]. However, as only 50 % of hamartomas will contain measurable fat attenuation on CT, this finding lacks sensitivity. The presence of calcification also helps to suggest a benign etiology. Patterns of calcification that are traditionally linked to benignity are diffuse, central, lamellated, or “popcorn” appearing. Diffuse, central, and lamellated calcification in a nodule is suggestive of a prior granulomatous process. Popcorn-appearing calcification is associated with hamartomas. A perifissural location of a solid nodule, i.e., contact with a fissural surface, is also a feature which suggests benignity [24, 25].

Unfortunately, features of benignity are present in the minority of incidentally discovered nodules (Fig. 18.4). Most lesions therefore must be considered to be indeterminate in nature. The only current guidelines for their management come from the Fleischner society with follow-up imaging recommended on the basis of nodule size and smoking history. It is important, however, to recognize that these are consensus guidelines, not supported by prospective randomized data. As well, the applicability of these guidelines in a cohort of patients being evaluated for TAVR is unclear [22]. What is known is that nodule size is strongly correlated with risk of malignancy, with nodules of <5 mm rarely being malignant (1 %), 5–10 mm nodules are more commonly malignant (6–28 %), and nodules of greater than 20 mm are often malignant (64–82 %) [26].

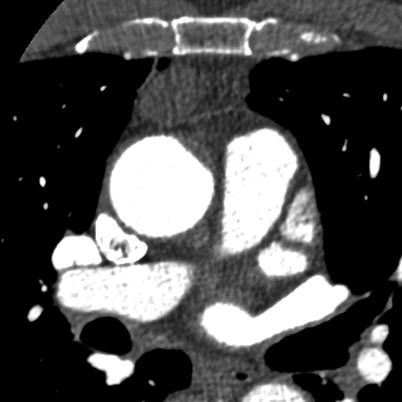

Fig. 18.4

A 71-year-old male patient with acute pulmonary emboli seen in the anterior and lateral segmental vessels to the right lower lobe

Subsolid (semisolid and ground glass) nodules present more of a problem as widely accepted guidelines are not yet firmly established (Fig. 18.5). A 2009 paper by Godoy and Naidich provides interim guidelines for the management of subsolid nodules [27]. This paper suggests no follow-up is required for isolated ground glass lesions measuring less than 5 mm. Solitary ground glass lesions measuring 5–10 mm are followed at 3–6 months and if stable at yearly intervals for at least 3 years; if the lesion increases in size, a surgical opinion may be sought. For ground glass lesions greater than 10 mm in size, a follow-up at 3–6 months is recommended; if the lesion persists or increases in size, a surgical opinion is suggested. Mixed ground glass/solid nodules of any size are found to be malignant in up to one-third of cases, and a surgical opinion is suggested when these lesions are found [28]. Importantly, the biology of these lesions is typically indolent, and therefore, their impact on prognosis in the TAVR patient population is unclear. As such, the presence of such a lesion would not likely prevent TAVR. It may be most reasonable to seek a pulmonary referral for patients with such nodules >6 mm in size for risk assessment and to help provide guidance regarding the value of further imaging or biopsy.

Fig. 18.5

A 78-year-old male, 2.1 cm presumed thymoma, and no associated clinical findings

Although the phase of contrast on an MDCT for TAVR planning is timed to optimally assess the systemic arterial structures, there is commonly adequate contrast in the pulmonary arterial system for the evaluation and exclusion of pulmonary emboli (Fig. 18.6). A meta-analysis of incidentally discovered pulmonary emboli suggests a prevalence of 2.6 % [29]. Hospitalization at the time of examination and the presence of cancer were potential predictors of pulmonary emboli (odd ratios 4.27 and 1.80, respectively) [29]. The clinical significance of such findings, especially if the clot burden is small (i.e., only subsegmental), is uncertain. Despite this uncertainty, convincing PE noted on a TAVR screening examination should be reported to the TAVR team on an urgent basis.

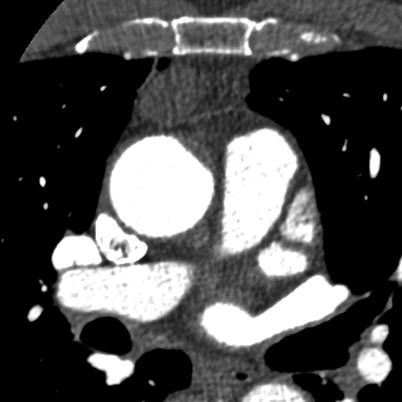

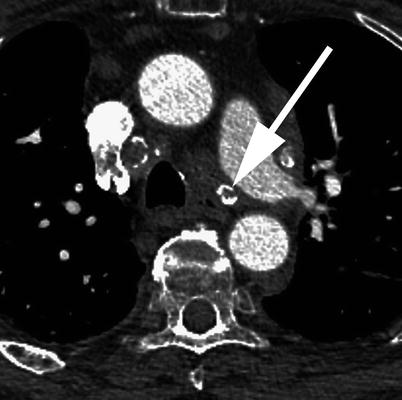

Fig. 18.6

A 82-year-old male, with multiple mediastinal lymph nodes. Some of which demonstrate calcification (arrow)

Evaluation of the Mediastinum

Incidentally discovered mediastinal lesions on MDCT are rare, occurring in less than 1 % of individuals having MDCT for the purposes of lung cancer screening [30]. In this study by Henschke et al., the most common incidental mediastinal lesion detected were lesions of thymic origin (Fig. 18.7). Thymomas account for the most common primary neoplasm of the mediastinum in patients over 40 year of age [31]. They tend to present in the fifth to sixth decades of life. Management remains controversial; however, surgical resection is suggested with lesions approaching 3 cm, due to propensity for recurrence and increase in technical difficulty in removing larger lesions [32]. Lesions smaller than 3 cm can be followed to ensure stability.

Fig. 18.7

A 85-year-old male patient with multiple avidly enhancing lesions in the liver; an enhancing lesion was also seen in the pancreas (not shown), felt to represent metastatic disease. A remote history of melanoma resection was obtained

Incidentally detected mediastinal or hilar adenopathy can be seen in up to 9 % of MDCT examinations of the chest [30]. Lymph nodes in the mediastinum and hilum are considered abnormal or pathologic when their short axis diameter is greater than 1 cm [33]. Evaluation of the lymph nodes for calcification, lung parenchymal findings, and patient history are important first steps in work-up, particularly in regard to discovery of a possible underlying cause (Fig. 18.8) [34]. Size of incidentally detected lymph nodes is correlated with risk of malignancy [35]. A Dutch study indicated that PET was rarely useful in evaluation of incidentally discovered lymph nodes as FDG avidity was demonstrated in 86 % of cases, none of which demonstrated malignancy on biopsy [33]. These researchers conclude that in the absence of a known primary malignancy workup of incidentally discovered adenopathy need not be aggressive, but provide no definitive recommendations with regard to follow-up. Despite the low likelihood of incidentally detected mediastinal adenopathy resulting in an ultimate diagnosis of malignancy if clinical uncertainty persists surgical or transbronchial tissue sampling may be required [34].

Fig. 18.8

A 67-year-old male patient in which the spleen demonstrates a typical serpiginous-appearing enhancement in the early arterial phase

Evaluation of the Solid Abdominal Organs

Liver

Liver lesions are commonly identified at autopsy with an estimated prevalence of 50 % [36]. The evaluation and characterization of focal liver lesions on an arterial phase CT examination, such as a TAVR protocol, are fraught with pitfalls. Enhancement characteristics of a liver lesion are important in determination of the underlying pathology. Early arterially enhancing lesions have a broad differential diagnosis, including both benign entities (hemangioma and fibronodular hyperplasia) and lesions with malignant potential or frank malignancy (adenoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and vascular metastases) (Fig. 18.9). In addition, on early phase examinations, an area of enhancement may represent a vascular shunt, also known as a transient hepatic attenuation difference (THAD). Definitive characterization of focal liver lesions is often not possible owing to the lack of portal venous or delayed phase examination. Another issue with detection of liver lesions on MDCT so soon after contrast has been injected is that lack of enhancement may indicate a truly hypovascular lesion, which may be a cyst (<20 HU), indeterminate solid lesion (>20 HU), or even a hypervascular lesion which is not categorized as such because the phase of contrast is too early for the lesion to demonstrate enhancement.

Fig. 18.9

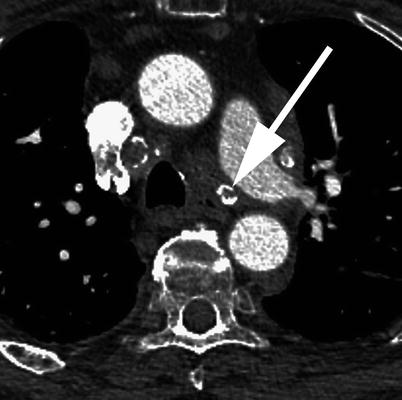

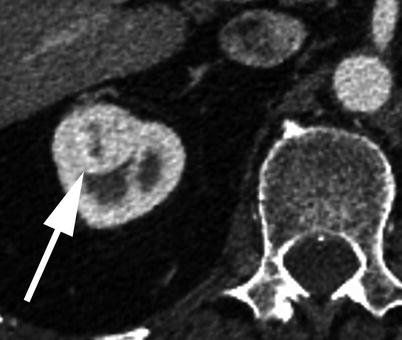

A 84-year-old male patient with a 1.5 cm left adrenal lesion (arrow)

The ACR recently provided a guideline position paper for the management of incidentally detected liver lesions [1]. Lesion size, patient demographics, and patient risk are key factors in determining appropriate management. The ACR group uses 40 years of age as a discriminator between low and average risk patients. The high-risk group includes individuals of any age with known primary malignancy, cirrhosis, or other risk factors which predispose to hepatic malignancy such as hepatitis, sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, hemochromatosis, hemosiderosis, and hepatic dysfunction. If a lesion is felt to require further workup, modalities besides CT can be employed. Ultrasound is of use if based on the MDCT findings it is felt that the lesion is likely to be cystic in nature; however, if the lesion shows enhancement, ultrasound will have limited specificity compared to MRI. Biopsy of focal liver lesions is generally safe but does have an associated morbidity and mortality of 2–5 and 0.05 %, respectively [37].

In a patient without high-risk clinical features, lesion size and morphology are utilized as the primary discriminating factors. Lesions of any attenuation under 5 mm are not to be followed up and simply referred to as “indeterminate.” Lesions 0.5 to 1.5 mm that have no suspicious features (ill-defined margins, enhancement, heterogeneity, enlargement from a prior exam) can be considered benign; lesions in this size range with suspicious features are followed up in 6 months with CT or MR. Lesions 0.5–1.5 mm which enhance avidly and rapidly (i.e., lesions enhancing in the arterial phase) can be considered benign. Lesions over 1.5 cm are considered benign if low attenuation (<20 HU) with no suspicious features. Further evaluation with MRI is suggested in patients over 40 years of age if any suspicious features are present. Avidly enhancing lesions over 1.5 cm may be considered benign in low-risk patients of any age, although, if possible, evaluation with MR may be useful [1].

In high-risk patients, recommendations are to either determine the lesion is benign via further imaging or to obtain a definitive diagnosis via biopsy if the lesion cannot be determined to be nonaggressive and is over 1.5 cm [1].

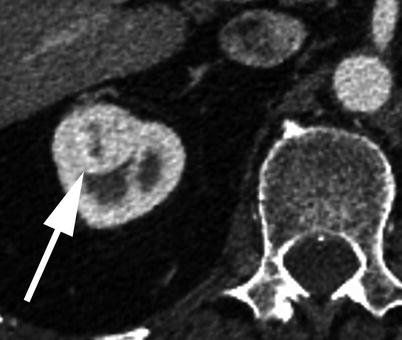

Spleen

The spleen is a particularly difficult solid organ to evaluate on an arterial phase MDCT due to the varied and occasionally bizarre and heterogeneous enhancement during this phase of imaging (Fig. 18.10). Thankfully, the spleen is a rare site of isolated metastatic disease and an uncommon location of primary malignancy. Splenic incidentalomas tend to be rare and when found are usually benign in the absence of a known history of malignancy [38, 39].

Fig. 18.10

A 88-year-old male patient with a heterogeneous solid right renal lesion measuring 2.5 cm (arrow), presumed to represent a renal cell carcinoma

Pancreas

Incidentally detected pancreatic lesions pose multiple issues regarding management. Simple cystic lesions are commonly detected in asymptomatic individuals (up to 3 % of abdominal CT examinations) [40]. Additionally, even when not demonstrating concerning morphology (enhancing septa, nodular solid component, associated pancreatic duct dilatation), there is a reasonable chance the lesion will eventually demonstrate malignant pathology [41]. MRI exams of the abdomen detect pancreatic cysts in nearly 20 % of cases [42]. This discrepancy between imaging modalities provides fodder for the argument that such lesions are unlikely to alter mortality.

One explanation for this is that simple cystic pancreatic malignancies grow extremely slowly, if at all. This knowledge of the natural history has lead to the body of evidence that such lesions can be managed with surveillance [43].

Size of a cystic lesion and symptomatology are important factors in determining management. In the absence of symptoms, it is highly likely that a cystic lesion under 3 cm is benign [44]. It is felt that lesions under 2 cm need only be followed up at 1 year to ensure stability. Lesions 2–3 cm should have a noninvasive study (MRI with contrast and MRCP). The ACR’s Incidental Findings Committee suggests aspiration can be attempted on lesions greater than 3 cm [1].

While lesions greater than 3 cm may be considered for operative management if they cannot be characterized as a stable IPMN or serous cystadenoma, this recommendation may be at odds with other studies evaluating management of such lesions in patients such as those screened for TAVR. A study by Weinberg et al. suggests that in an older patient cohort management beyond surveillance is a detriment to quality of life for asymptomatic patients with pancreatic cysts [45]. This is an important concept to keep in mind with typical TAVR patients.

Solid pancreatic lesions are generally considered malignant until proven otherwise. Lesions that enhance in the arterial phase would include islet cell tumors and metastatic deposits to the pancreas from a vascular primary tumor (i.e., renal cell or melanoma). A history of a primary malignancy or endocrine symptoms should be elicited when such lesions are discovered incidentally on MDCT.

Adrenals

Incidentally discovered adrenal lesions are common, occurring in up to 7 % of MDCTs which image this area [46]. While the adrenal gland is a common site of metastatic disease, the vast majority of incidentally discovered adrenal lesions, even in patients with known malignancy, are nonhyperfunctioning adrenal adenomas [46]. In patients with no known malignancy, greater than 98 % of incidentally discovered adrenal lesions are benign [47]. If further management is felt to be warranted, the first step would be to evaluate the adrenal lesion for findings that would suggest a specific benign diagnosis, i.e., macroscopic fat to suggest a myelolipoma. Given that a TAVR MDCT is performed with the use of iodinated contrast in the arterial phase, caution should be given with regard to assessment of lesion attenuation (Fig. 18.11). On a non-contrast MDCT, if the adrenal lesion in question is homogeneous and measures less than or equal to 10 HU, it can be assumed to represent a lipid rich adenoma, with no further workup suggested [1]. If the Hounsfield measurement is greater than 10, either an MR or contrast-enhanced CT with washout is performed. Although the washout protocol CT is the ultimate diagnostic imaging tool in assessment of adrenal lesions, MRI can be helpful in this algorithm and is an attractive option, especially in younger patients where radiation dose is a concern. Even in lesions that are not “lipid rich” on the basis of the non-contrast CT, a percentage of them will still demonstrate signal loss on out-of-phase MRI, allowing a diagnosis of an adrenal adenoma to be made with confidence [48].

Fig. 18.11

A 84-year-old male patient with marked circumferential thickening of the hepatic flexure of the colon (arrow). A colonic adenocarcinoma was subsequently resected

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree