Extremity Patterns

EX2. Calcified Intraarticular Loose Bodies

EX3. Change in Size and Shape of Epiphyses

EX4. Cystic Lesions of Extremities and Ribs

EX5. Aggressive Osteolytic Lesions of Extremities and Ribs

EX6. Osteosclerotic Bone Lesions

EX8. Radiodense Metaphyseal Bands

EX9. Radiolucent Metaphyseal Bands

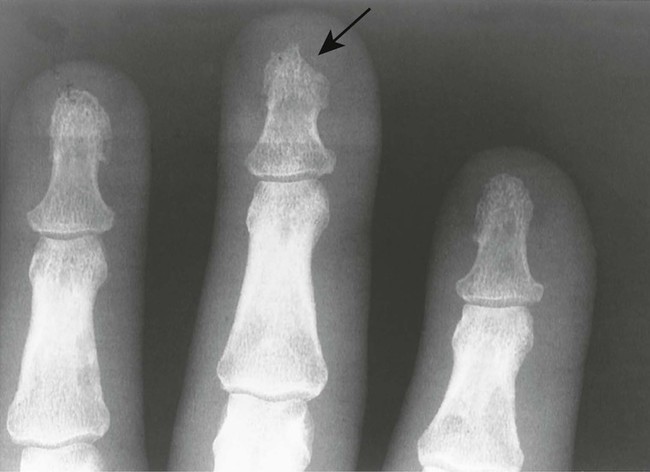

EX1 Acro-osteolysis

Acro-osteolysis represents bone resorption of the distal phalanges of the hands and feet. A wide range of congenital and acquired etiologies are responsible. Swelling or atrophy of the overlying soft tissues may be present.

| Disease | Comments |

| More Common | |

| Hyperparathyroidism (Fig. 18-1) (p. 928) | Overproduction of parathormone resulting from primary or secondary factors affecting the parathyroid glands; the disease is marked by osteopenia, osteosclerosis, bone resorption, and soft-tissue and vascular calcification; vertebrae appear osteopenic with characteristic, homogeneous, radiodense bands traversing horizontally at each end of the vertebrae (“rugger jersey” spine); resorption of the distal tufts and radial side of the digits is characteristic |

| Neurotrophic disease (p. 606) | Bone resorption secondary to diabetes, leprosy, tabes dorsalis, syringomyelia, meningomyelocele, and congenital indifference to pain |

| Psoriatic arthritis (p. 520) | Arthritis occurring in fewer than 7% of patients with psoriasis; this condition involves the carpal, interphalangeal (distal interphalangeal common), and less commonly the sacroiliac joints; the digits are marked by nail pitting, swelling of the soft tissues, and less commonly erosions of the distal tufts, which result in a tapered appearance of the distal phalanges |

| Scleroderma (progressive systemic sclerosis) (Fig. 18-2) (p. 498) | Disease of small vessels and organ fibrosus; the soft tissues of the hands and feet undergo atrophy and calcification in addition to resorption of distal phalanges |

| Thermal injury (Fig. 18-3) | Resorption of the distal phalanges secondary to burns or frostbite injury; characteristically, the thumb is spared in frostbite injury because the individual makes a fist around the thumb, protecting it from low temperatures |

| Less Common | |

| Arteriosclerosis obliterans | Arteriosclerosis producing narrowing and occlusion of the arterial lumen; the resulting ischemia causes bone resorption |

| Lesch-Nyhan syndrome | Disorder characterized by hyperuricemia and uric acid urolithiasis, mental retardation, spastic cerebral palsy, and biting (self-mutilation) of fingers and lips |

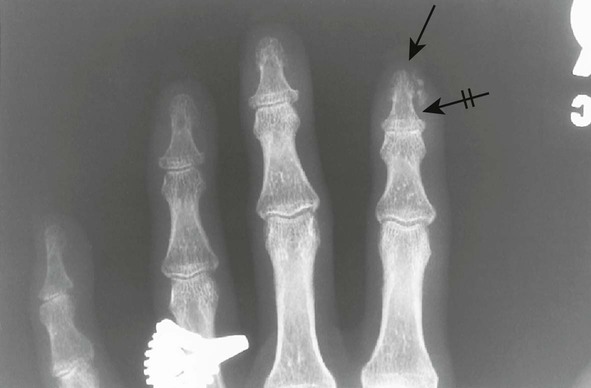

| Pyknodysostosis (Fig. 18-4) (p. 462) | Hereditary sclerosing dysplasia of bone marked by short stature, dense bones (often with transverse fractures), hypoplastic angle of mandible, wormian bones, delayed closure of the fontanelles, and hypoplasia of the terminal phalanges |

| Raynaud disease | Spasms of the digital arteries leading to distal tuft resorption, blanching, and pain in the hands; condition is associated with scleroderma |

| Sarcoidosis (Fig. 18-5) (p. 1240) | Systemic granulomatous disease most pronounced in the lungs; less commonly, the disease involves arthritis or acro-osteolysis of the hand with coarsened trabeculae and well-defined osteolytic lesions |

| Vinyl chloride exposure | Systemic toxicant, abbreviated VC, which is particularly noxious to endothelium and is used for polyvinyl chloride (PVC) synthesis; occupational exposure is associated with acro-osteolysis and neuritis; the acro-osteolysis presents as transverse, band-like radiolucent defects of the distal phalanges, usually the thumb |

EX2 Calcified Intraarticular Loose Bodies

Loose intraarticular bodies typically are found in the large weight-bearing joints (e.g., knees). Degenerative disease probably represents the most common etiology. Noncalcified intraarticular bodies are not visible on plain film radiographs and require specialized imaging to detect their presence. Symptoms are variable, ranging from acute joint locking to asymptomatic states.

| Disease | Comments |

| More Common | |

| Degenerative joint disease (p. 544) | Very common, progressive, noninflammatory disorder involving the large weight-bearing joints and smaller joints of the hand; the radiographic appearance is characterized by joint subluxation, articular deformity, nonuniform reduction in joint space, marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, subchondral bone cysts, and intraarticular loose bodies; the knee is most commonly involved; this disease usually is seen in elderly patients |

| Trauma | Single or multiple loose bodies representing bone, ligament, or meniscal fragments arising from trauma; fragments may not be calcified and therefore are not visible on plain film radiography |

| Less Common | |

| Neuropathic (Charcot) joint (p. 606) | Destructive arthropathy secondary to altered joint sensory innervation, resulting in either unchecked repetitive injury as a result of absence of pain or loss of trophic influences of innervations with local hyperemia and bone resorption; varieties are atrophic and hypertrophic; hypertrophic changes include premature and advanced degeneration marked by dislocation, destruction, intraarticular loose bodies (debris), and disorganization; the knee, hip, ankle, and lumbar spine are commonly affected |

| Osteochondrosis dissecans (p. 743) | Complete or incomplete separation of a portion of the joint cartilage and subjacent bone from a traumatic or osteonecrotic etiology; occurs in adolescence; the knee usually is involved, classically the lateral aspect of the medial condyle; fragments that do not reunite exist as intraarticular loose bodies |

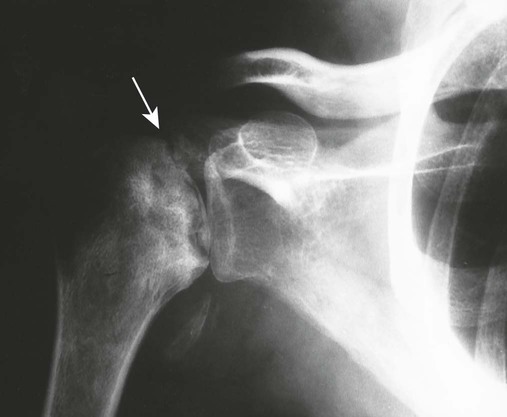

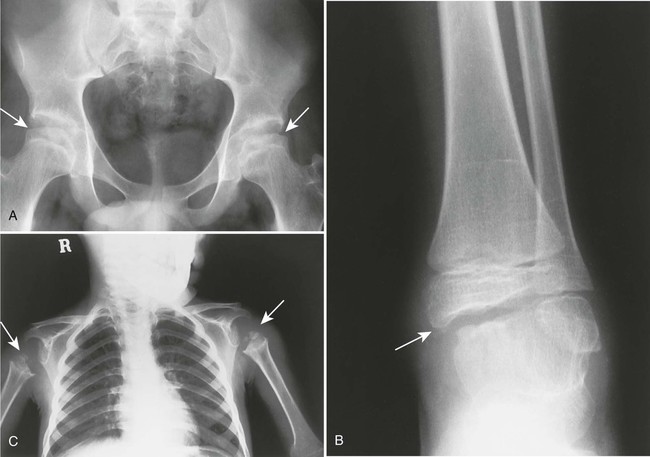

| Synovial osteochondromatosis (Figs. 18-6 and 18-7) (p. 875) | Nonneoplastic hypertropic metaplasia of synovial tissue, producing multiple cartilage nodules, which eventually may ossify; nodules detach to become loose bodies in the joint, bursal, and tendon sheath spaces; this condition may be asymptomatic or produce acute pain with joint locking; in adults, the knee, hip, ankle, and elbow are most commonly affected |

EX3 Change in Size and Shape of Epiphyses

Alterations in the size and shape of epiphyses are related to traumatic, congenital, and metabolic disturbance of bone growth or may represent normal variants of bone growth and development. Joint effusion or bleeding may cause overgrowth, as is the case in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and hemophilia. A long list of eponyms is applied to irregularity of the epiphysis associated with avascular necrosis.

| Disease | Comments |

| More Common | |

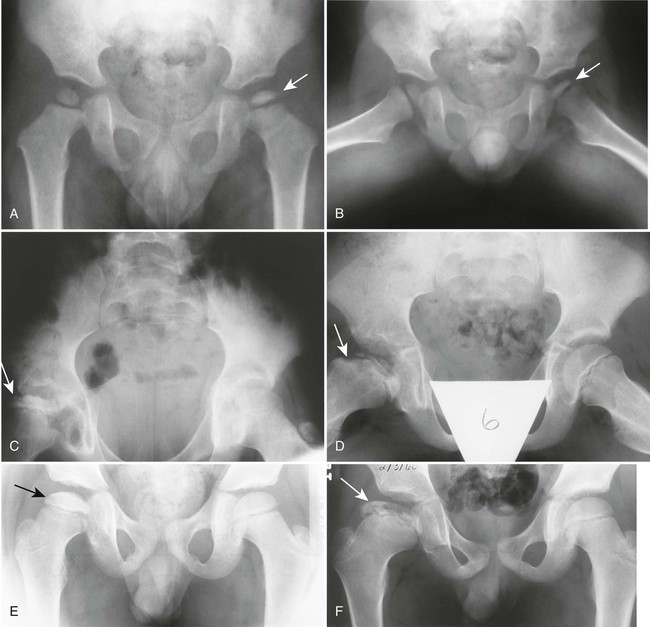

| Avascular necrosis (Figs. 18-8 to 18-12) (p. 766) | Etiologies related to vascular insufficiency (e.g., sickle-cell disease, steroid therapy, trauma, alcoholism); necrosis gives the epiphyses a fragmented, radiodense, thin, and small appearance; proximal femoral epiphysis is most common; weight bearing, joint effusion, and decreased range of motion cause pain |

| Trauma | Traumatic separation or changes in the size and shape of the epiphysis; including battered child syndrome |

| Less Common | |

| Achondroplasia (p. 425) | Congenital defect of enchondral bone formation, producing characteristic rounded lumbar “bullet-nosed” vertebrae, lumbar kyphosis, posterior scalloping of the vertebrae, increased intervertebral disc height, flattened vertebral bodies, and narrowed spinal canal; the pelvis may appear hypoplastic; epiphyses may appear “cone shaped”; cone-shaped epiphyses also are seen with sickle-cell disease, various congenital dysplasias, and as a normal variant |

| Congenital syndromes (Fig. 18-13) | Chondrodysplasia punctata (Conradi disease), multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (Fairbank-Ribbing disease), Down syndrome, and other congenital syndromes associated with irregularity, fragmentation, and stippling of multiple epiphyses |

| Cretinism (p. 934) | Juvenile hypothyroidism during the first year of life resulting from thymic agenesis or low maternal iodine intake during pregnancy; delayed skeletal and mental development result; epiphyses appear stippled during infancy and fragmented during childhood; cone-shaped epiphyses may develop; the proximal femoral epiphyses are most commonly involved |

| Hemophilia (p. 779) | Inherited X-linked defect of blood coagulation marked by a permanent tendency toward hemorrhage; hemarthrosis is associated with red swollen joints, osteoporosis, precocious degeneration, and an enlargement of the epiphyses; knee, ankle, and elbow are most common; rarely, osteolytic expansile bone lesions (hemophilic pseudotumors) develop |

| Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (p. 490) | Chronic arthritis beginning in childhood (before 16 years of age) manifesting as one of several clinical types; characteristic large, overgrown, “ballooned” epiphyses, osteoporosis, joint fusion, periostitis, and gracile long bones are secondary to hyperemia |

| Normal variant | May be represented by symmetric, fragmented, or irregular appearance of the epiphysis; these variants may mimic osteonecrosis |

| Rickets (Fig. 18-14) (p. 944) | Infantile or juvenile osteomalacia secondary to vitamin D deficiency, characterized clinically by irritability, listlessness, and generalized muscle weakness; an overproduction and deficient calcification of osteoid tissue results in disturbances of bone growth with resulting deformity; fractures are common; epiphyses may appear indistinct, epiphyseal plates are wide, and metaphyses appear frayed |

| Scurvy (Barlow disease) (Fig. 18-15) (p. 946) | Defective osteogenesis occurs secondary to abnormal collagen from vitamin C deficiency, beginning between 6 to 14 months of age; the disease is marked clinically by irritability, bleeding gums, tendency toward hemorrhage, and tenderness and weakness of lower limbs; epiphyses appear radiolucent with surrounding sclerotic rim (Wimberger sign or ring epiphyses) |

EX4 Cystic Lesions of Extremities and Ribs

This pattern lists lesions occurring mainly in the epiphyses and metaphyses of long bones that appear as solitary or, less commonly, multiple well-defined holes in the bone. The age of presentation, host bone, presence of calcification, and symptoms are useful discriminators for the list of lesions. The popular mnemonic FEGNOMASHIC includes many of this list: fibrous dysplasia, enchondroma (and eosinophilic granuloma), giant cell tumor, nonossifying fibroma, osteoblastoma, metastatic disease (and multiple myeloma or plasmacytoma), aneurysmal bone cyst, simple bone cyst, hyperparathyroidism (and hemophilic pseudotumors) infection, and chondroblastoma (and chondromyxoid fibroma).

The full list may be modified if the presentation is of multiple lesions or is epiphyseal in location. Multiple lesions suggests the following etiologies: infection, fibrous dysplasia, metastasis, multiple myeloma, subchondral cysts, hyperparathyroidism, enchondromatosis, and eosinophilic granuloma. An epiphyseal location suggests infection, giant cell tumor, chondroblastoma, subchondral cyst, pigmented villonodular synovitis, and interosseous ganglion. Cystic bone lesions occurring in patients younger than 30 years of age most often result from eosinophilic granuloma, aneurysmal bone cyst, simple bone cyst, chondroblastoma, and nonossifying fibroma or fibrous cortical defect.

The mnemonic FAME describes cystic rib lesions: fibrous dysplasia, aneurysmal bone cyst, metastatic disease (and multiple myeloma), and enchondroma.

| Disease | Comments |

| More Common | |

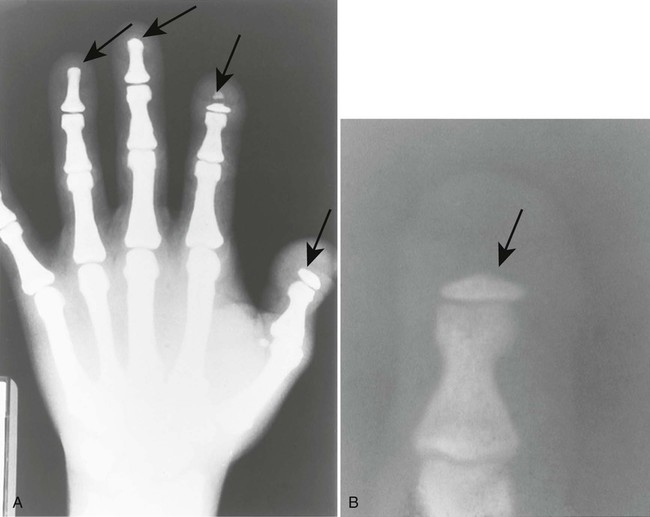

| Enchondroma (Fig. 18-16) (p. 843) | Solitary or multiple benign cystic cartilage lesion(s), appearing most often in the small bones of the hands and feet; stippled cartilage matrix is seen typically; no periostitis or pain is present unless fractured |

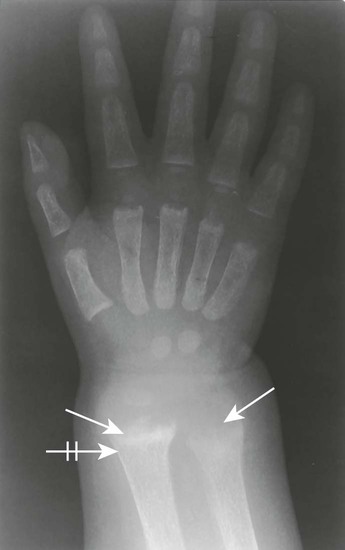

| Fibrous cortical defect or nonossifying fibroma (Figs. 18-17 and 18-18) (p. 868) | Very common, benign asymptomatic cystic bone lesions seen before the age of 30 years; marked by a thin sclerotic border without matrix calcification; common in the lower extremities, particularly around the knee |

| Fibrous dysplasia (Fig. 18-19) (p. 861) | Disturbance of bone maintenance in which bone is replaced by abnormal proliferation of fibrous tissue, possibly involving one or multiple bones; the matrix often has a characteristic “ground-glass” radiodensity; lesions may be surrounded by a thick rind of bone sclerosis; the most common locations are femur, ribs, tibia, craniofacial bones, and pelvis; lesion should not be painful |

| Infection (Fig. 18-20) | May occur at practically any location during any age; if found in a subarticular location, the joint is often involved with effusion; soft-tissue mass and central bone sequestrum often are present; appearance varies from cystic to sclerotic; alternatively, infections may present as aggressive bone lesions |

| Metastatic disease (Fig. 18-21) (p. 1415) | Common cause of one or more osteolytic bone lesions in patients older than the age of 40 years; atypical presentations of expansile, bubbly, solitary geographic lesions are associated with primary lesions of the thyroid and kidney; purely blastic lesions occur most often from breast, prostate, gastrointestinal, bladder, and lung neoplasms |

| Simple (solitary) bone cyst (Figs. 18-22 and 18-23) (p. 900) | Fluid-filled cyst of uncertain etiology; the majority of cases are discovered before the age of 20 years; 90% of simple bone cysts are found in the proximal humerus and femur; bone cysts appear as mildly expansile, well-marginated, geographic lytic lesions in the metaphysis, less frequently in the diaphysis, or rarely in the epiphysis; fracture causes pain, otherwise, it is usually painless |

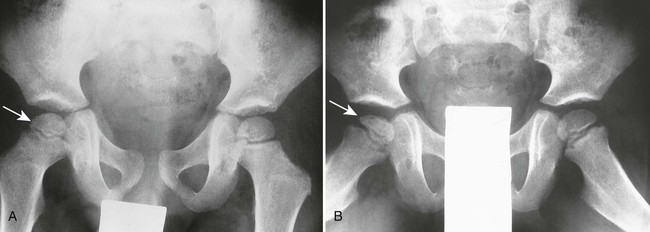

| Subchondral bone cyst (Figs. 18-24 to 18-26) | Related to arthritic or synovial disorder (osteoarthritis, gout, calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease, rheumatoid arthritis, hemophilia, intraosseous ganglion, amyloidosis, and avascular necrosis); this well-defined cyst is located in the epiphysis subjacent to the articular cortex |

| Less Common | |

| Adamantinoma (p. 904) | Also known as angioblastoma, a rare, locally aggressive or malignant lesion composed of epithelium-like cells in dense fibrous stroma; 90% are found in the middle third of the tibia; lesions appear as central or eccentric, slightly expansile, well-circumscribed, osteolytic lesions |

| Aneurysmal bone cyst (p. 892) | Solitary, benign, osteolytic lesion of bone characterized by cortical expansion, usually found in patients younger than 20 years of age; this bone cyst most commonly presents as an eccentric lesion in the metaphyses of long bones; typically it causes pain |

| Chondroblastoma (p. 848) | Rare, benign bone tumor arising in the secondary growth centers of long bones; usually in patients younger than 25 years of age; 50% demonstrate matrix calcification and a rim of surrounding sclerosis |

| Chondromyxoid fibroma (p. 851) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree