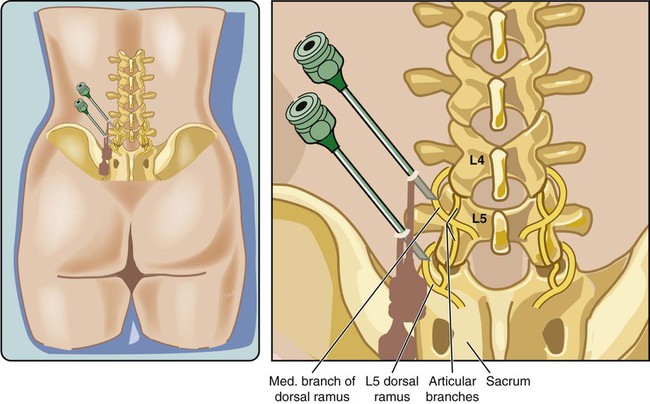

Back and neck pain are among the most common medical complaints in developed countries. Prevalence of spinal pain is estimated at 66% in the general population, with 55% to 90% reported as low back pain, 44% cervical, and 15% thoracic.1–3 Spinal pain is a significant burden on both the individual and society in terms of direct cost, economic loss, and suffering.1–3 Spinal pain is most common in people 18 to 44 years of age and ranks second for chief complaints for outpatient visits, third for surgical procedures, and fifth for hospitalizations.4 Most episodic symptoms resolve over days to weeks with only conservative therapy, but roughly a third of patients will progress to chronic pain, more commonly in smokers, women, and those with psychological distress, low physical activity, and other premorbid conditions.3 Differential diagnosis of spinal pain includes vertebral body pathology, vertebral disc disease, spinal stenosis, nerve entrapment syndromes, paraspinal muscle pain, and facet joint disease, along with extraspinal ailments such as cancer, gastric/duodenal ulcer, pancreatitis, aortic aneurysm, nephrolithiasis, prostatitis/cystitis, and postherpetic neuralgia. Often the etiology of spinal pain is elusive, but facet syndrome is thought to be the cause of chronic spinal pain in approximately 30% of people with low back pain, 55% of those with cervical pain, and 40% of thoracic pain.2,4–7 Diagnostic facet blocks should be part of an algorithmic approach to the clinical management of chronic spinal pain.5,8 Recent trends in utilization have shown exponential growth in the number of patients receiving facet interventions,9 as well as in the performance of facet interventions by non-physicians.10 The facet joint, also called the zygapophyseal or Z-joint, is a true synovial joint involved in the articulation of adjacent vertebral bodies.6 The two facet joints and the intervertebral disc make a tripod support for each spinal level. Involvement of this joint in spinal pain is called facet or zygapophyseal syndrome. The association of facet joint pathology and pain was first described in 1911 by Goldthwait and termed facet syndrome by Ghormley in 1933.6 Etiologies of facet syndrome include trauma, arthritis, inflammation, and degeneration.6 Facet syndrome typically presents as axial low back pain, neck pain, or headaches.11–15 Axial pain of thoracic facet origin has been described but is less common.16 The thoracolumbar juncture is vulnerable to facet injury from the abrupt transition in facet joint orientation from the coronal to sagittal plane that occurs there anatomically. The prevalence of lumbar facet arthrosis increases with advancing age.17 Greater than 50% of adults over 30 years of age demonstrate arthritic changes of the facet joints.18 The most commonly affected lumbar joint is the L4-5 facet joint, possibly owing to its sagittal orientation.19 Comorbid vascular disease is also a risk factor for facet degeneration.20 The symptoms of facet syndrome are nonspecific and overlap with other diagnoses. The pain may be confined to the axial lumbar spine or referred to the buttock and thigh.21 Pain may also have a pseudoradicular component but rarely radiates distal to the knee and is not exacerbated by the straight leg raise test.4–6,21 In the cervical spine, pain is in the neck itself or may be referred to the head (cervicogenic headache), shoulders, or scapula.11,12 Physical examination findings that suggest facet syndrome are pain aggravated by palpation of the paraspinal muscles, standing, spinal extension, and facet joint loading with rotation.4–7,13 Pain is usually ameliorated by sitting and flexing the spine. Diagnostic scoring systems with signs and symptoms of facet syndrome have been developed, but results have not been consistent. Furthermore, some suggest that the physical exam is only sufficient to rule out major neurologic injury but insufficient to diagnose the source of the pain.22 Radiologic or scintigraphic (bone scan) studies are neither sensitive nor specific for diagnosing facet syndrome. Facet syndrome is suggested by findings of degeneration and hypertrophy of the facet joints (spondylosis), but these changes are ubiquitous with aging. Furthermore, many people with radiographic spondylosis have no pain.4–6,17 Yet one study demonstrated that community hospital patients with spinal pain demonstrate an increased prevalence of increased uptake in the facet joint on single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).23 Because of these ambiguities, facet syndrome often is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. Spondylolisthesis may be comorbid with facet syndrome because displacement of the vertebral bodies produces stress on the facet joints.6 Similarly, prior spinal fusion can lead to adjacent segment degeneration (transition zone syndrome) and facet-mediated pain.24 In the acute and early chronic setting, conservative management should be considered. This may include physical therapy, analgesics, relative rest, acupuncture, or chiropractic manipulation.5 If conservative therapy fails after 6 to 12 weeks and there is no evidence of neurologic impairment on physical exam or major radiologic abnormality, the diagnosis of facet syndrome can be considered. Because the physical exam and radiologic studies are inadequate to diagnose facet syndrome, current practice is to anesthetize the nerves to the facet joint to confirm the diagnosis. There is a 30% to 40% placebo response to most pain therapies, including facet block, so a double-block protocol (i.e., repeated injection) with different local anesthetics with different durations of action can be used to reduce the false-positive rate.2,25 Placebo-controlled blocks could be done, but placebo studies are often unacceptable to the patient, physician, or payer. The facet joint may be anesthetized either by injecting local anesthetic directly into the joint capsule or by blocking the medial branch nerves that innervate the joint. Corticosteroid also can be injected into the joint to provide potentially longer-lasting analgesia through its antiinflammatory effect. • Oxygen and monitors (e.g., blood pressure, pulse oximetry, electrocardiography) • Sterile preparation and draping equipment • 25-gauge needle for skin infiltration with 1% lidocaine • 22-gauge spinal needles (3.5-inch length adequate for most blocks, but 5-inch needles may be needed for larger or obese patients) • Local anesthetic for facet block (preservative free): • Corticosteroid for facet injection: A facet is defined as a smooth, flat area of bone that is covered with cartilage and articulates with another bone. Each vertebra has four articular processes (facets), two superior and two inferior, that project from the lamina of the vertebra. Each facet articulates with the opposing facet of the adjacent vertebrae, sacrum, or skull to form a facet joint. Vertebral facet joints are true synovial joints with fibrous capsules that restrict range of motion of the spine and distribute axial weight, particularly with extension.26 The joint is arranged sagittally in the lumbar region, coronally in the thoracic region, and cephalocaudad oblique in the cervical spine. The joints are less defined in the cervical spine, allowing for a greater range of motion. The anterior portion of the joint is in close proximity to the ligamentum flavum and may actually fuse with the joint. Innervation of the lumbar facet joint is from the medial branch nerve at the spinal level of the joint and also from one level above (Fig. 165-1).26 The medial branch nerve is a derivative from the dorsal rami of the nerve root exiting the spinal cord and also innervates the interspinous ligament and the multifidus and rotatores muscles.26 The nerve travels off the dorsal rami, around the inferior base of the superior articular process, then divides such that some fibers travel superiorly to innervate the superior facet joint of its respective vertebrae. Other fibers continue inferiorly to innervate the facet joint of the vertebra one level below. The L5 median branch travels inferiorly over the sacral ala before it travels around the base of the superior articular process of the sacrum.26 Of all lumbar medial branch nerves, the L5 dorsal ramus has the most consistent location over the sacral ala. The remaining medial branches either lie at the junction of the transverse process and the corresponding articular pillar or slightly above or below this junctional location. The thoracic dorsal medial branch nerves (T1-T4, T9-T10) cross the superolateral corners of the transverse processes then pass medially and inferiorly across the posterior surfaces of the transverse processes at each level.27 Exceptions to this pattern occur at the midthoracic level (T5-T8), where the inflection point occurs more superiorly to the superolateral corner of the transverse process. The course of the midthoracic medial branches makes their routine blockade or radiofrequency denervation somewhat unpredictable. The T11 dorsal medial branch courses along the lateral margin of the superior articular process of T12, and the T12 dorsal medial branch assumes a course analogous to that of the lumbar medial branches. Although radiologic imaging cannot reliably diagnose facet syndrome, it is invaluable in performing facet injections and medial branch blocks. Traditional fluoroscopy (x-ray fluoroscopy) is typically used, but other modalities have been described, such as ultrasound28 and computed tomography (CT).29 Similarly, CT-fluoroscopy has been utilized for lumbar diagnostic facet injections29 and facet rhizotomy30 and may provide more accurate needle placement, more reliable blocks, and better pain control. However, a direct comparison between CT and fluoroscopy-guided lumbar facet rhizotomy demonstrated equal reduction in Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores.31 Recently, laser irradiation of the dorsal surface of the facet joint capsule has been shown effective in reducing pain from lumbar facet syndrome.32 Use a radiopaque marker to identify the desired skin entry point. Anesthetize the skin with 1% lidocaine and a 25-gauge needle. With a posteroanterior (PA) view, insert the styleted 22-gauge needle and guide the tip to the superior, posterior, and medial border of the transverse process, (i.e., at the junction of the transverse process and superior articular process). This can be done by intentionally contacting the lamina overlying the pedicle and then walking off the bone superiorly (Fig. 165-2). It is not necessary to move completely off the transverse process, merely approaching the edge is sufficient. Needle tip position can be confirmed in an oblique view as well (Fig. 165-3). After negative aspiration for blood, diagnostic injection is performed with 0.3 to 1 mL of 1% lidocaine or 0.5% bupivacaine. The sacral ala must be identified for L5 medial branch blocks (Fig. 165-4; also see Fig. 165-3

Facet Joint Injection

Clinical Relevance

Indications

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy

Approach

Diagnostic Lumbar Medial Branch Block

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Facet Joint Injection