and Arumugam Rajesh2

(1)

Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

(2)

Department of Radiology, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Tr Leicester General Hospital, Leicester, UK

Ovaries

Case 6.1

Brief Case Summary:

25 year old woman, annual check up

Imaging Findings

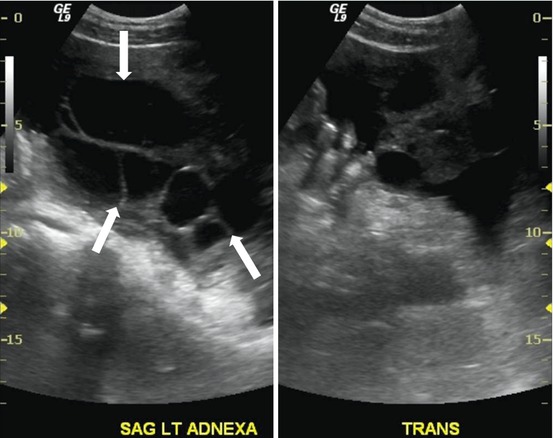

Grey scale transvaginal ultrasound demonstrates several small follicles at cortex of the left ovary (Fig. 6.1).

Fig. 6.1

Grey scale transvaginal ultrasound demonstrates several small follicles (arrow) at cortex of the left ovary

Differential Diagnosis

Polycystic ovaries

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Ovarian Follicles

Ovarian follicles are the basic units of female reproductive biology, and contain a single oocyte (immature ovum or egg). These structures are periodically initiated to grow and develop, culminating in ovulation of usually a single competent oocyte in humans. These eggs/ova are developed once every menstrual cycle.

Approximately 10 ovarian follicles begin to mature in during a normal menstrual cycle and out of these usually one will turn into a dominant ovarian follicle. During ovulation, the primary follicle forms the secondary follicle, then becomes the mature vesicular follicle (also known as a Graafian follicle). After rupture, the follicle turns into a corpus luteum. Rupture of the follicle can result in abdominal pain (Mittelschmerz) and should be considered in the differential diagnosis in women of childbearing age who present with pain.

In the normal physiological state, one of the follicles typically becomes a dominant follicle which subsequently grows up to 2.9 cm. If the follicle is larger than 3.0 cm, then it is considered a follicular cyst.

On ultrasound following maturations under the development of gonadotropins, follicles can be seen as round, thin-walled, anechoic, less than 1 cm. in diameter around the ovary.

On MRI, ovarian follicles and follicular cysts may be seen rounded structures located at cortex of ovary. Signal characteristics within the follicles include T2 high signal intensity.

Pitfalls

The presence of multiple peripheral small follicles on a background of ovarian enlargement and stromal hypertrophy should raise the suspicion of polycystic ovaries although polycystic ovarian syndrome is a clinical diagnosis.. Compared with polycystic ovaries, ovarian follicles tend to be fewer in number and larger, up to 10 mm in diameter.

Teaching Point

Ovarian follicles are typically small, less than 1 cm in diameter, thin-walled, and anechoic on ultrasound and have high T2 signal intensity on MRI.

Case 6.2

Brief Case Summary

30-year-old female; check up, healthy

Imaging Findings

Gray scale transvaginal US (arrow, Fig. 6.2) shows a thin-walled, unilocular well-defined anechoic cyst in right ovary. Transverse contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a well-circumscribed, low attenuation cyst (arrow, Fig. 6.3). Axial T2 MR image (arrow, Fig. 6.4) shows high signal intensity of the cyst.

Fig. 6.2

Gray scale transvaginal US (arrow) shows a thin-walled, unilocular well-defined anechoic cyst in right ovary

Fig. 6.3

Transverse contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a well-circumscribed, low attenuation cyst (arrow)

Fig. 6.4

Axial T2 MR image (arrow) shows high signal intensity of the cyst

Differential Diagnosis

Surface epithelial tumor, Endometrioma, Ovarian dermoid

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Follicular cyst

Occasionally the dominant maturing ovarian follicle fails to ovulate and does not involute. When the follicle is larger than 3 cm, it is considered an ovarian follicular cyst. They are typically 1–3 cm and rarely exceed 6 cm. Follicular cysts can have thin septations, focal thickening of the wall or increased attenuation. No solid nodular components should be present. On MRI, cysts are T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense, however, the content may vary if complicated by hemorrhage. Spontaneous resolution of the follicular cysts is common.

Pitfalls

Clot in hemorrhagic cysts can mimic a solid nodule on US, but should not demonstrate flow on Doppler US.

Teaching Point

Follow-up ultrasound in the premenopausal woman, should demonstrate resolution of follicular cysts after the next menstrual cycle.

MRI is helpful in distinguishing hemorrhagic cystic from solid lesions.

Case 6.3

Brief Case Summary

25-year-old female with pelvic pain

Imaging Findings

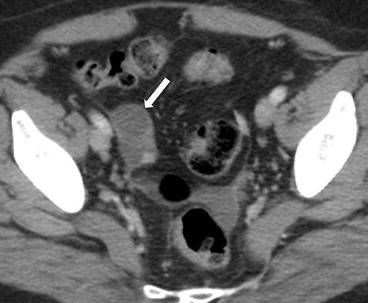

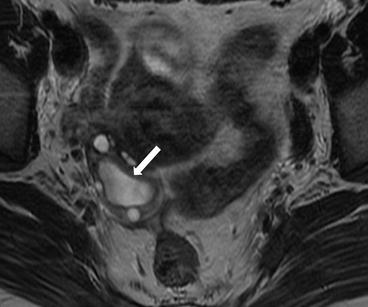

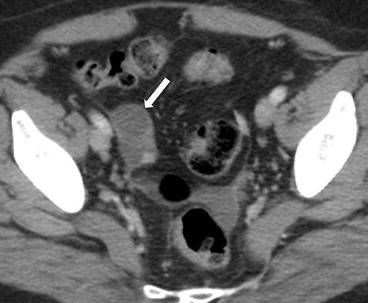

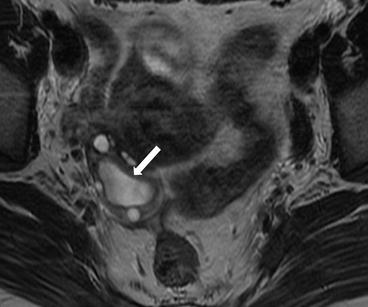

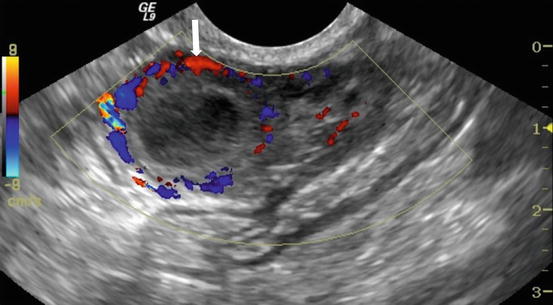

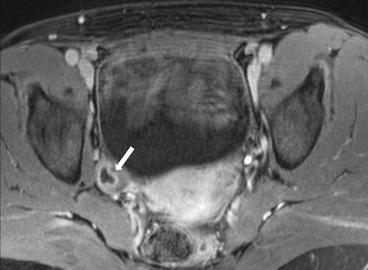

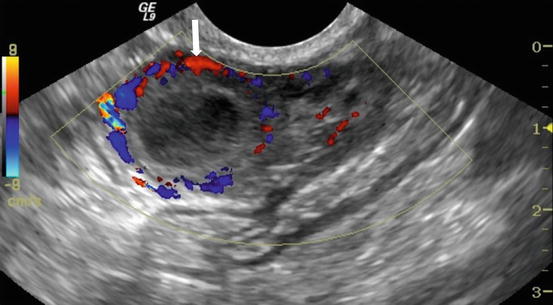

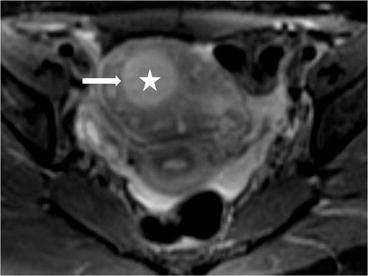

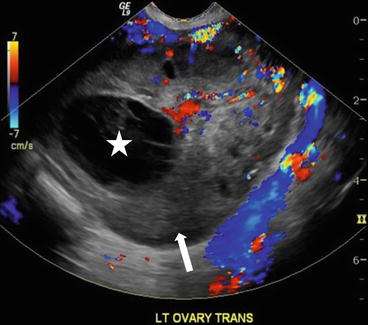

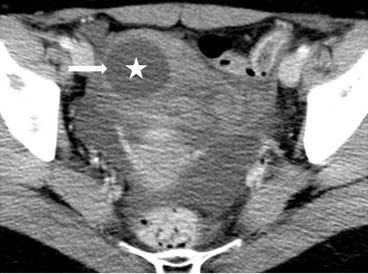

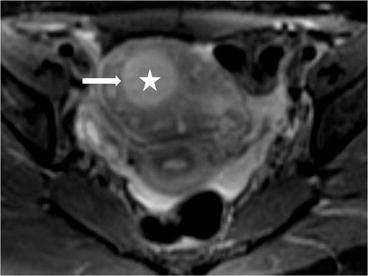

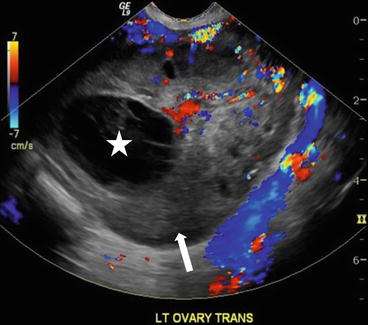

Gray scale transvaginal US shows a thick-walled ovary cyst (arrow, Fig. 6.5). Color Doppler US shows a “ring of fire” of increased vascularity of the thick-walled cyst with internal echogenic content (arrow, Fig. 6.6). Contrast-enhanced CT (Fig. 6.7) and MRI (Fig. 6.8) shows wall enhancement of the right ovarian cyst.

Fig. 6.5

Gray scale transvaginal US shows a thick-walled ovary cyst (arrow)

Fig. 6.6

Color Doppler US shows a “ring of fire” of increased vascularity of the thick-walled cyst with internal echogenic content (arrow)

Fig. 6.7

Contrast-enhanced CT shows wall enhancement (arrow) of the right ovarian cyst

Fig. 6.8

MRI shows wall enhancement (arrow) of the right ovarian cyst

Differential Diagnosis

Endometrioma, Ovarian abscess, Cystic ovarian tumors

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Corpus lutein cyst

After ovulation and release of the oocyte, there is proliferation of the granulosa cells which are along the inner lining of the cyst. The dominant follicle collapses and the proliferation of the granuloma cells form the corpus luteum of menstruation.

The corpus luteum degenerates over 14 days and becomes a scarred corpus albicans. The corpus luteum can seal and contain fluid or blood and form a corpus luteum cyst. The corpus luteum cysts may grow to 1–10 cm in size but are usually less than 4 cm in size.

Corpus luteum cysts are often incidental findings and asymptomatic unless complicated by hemorrhagic or torsion. On US, the appearance varies but commonly they are typically small complex cysts and with color Doppler, the “ring of fire” sign can be seen in the cyst wall where there is increased vascularity. On MR, the cyst is T1 hypointense, T2 hyperintense with a thick wall but the signal can vary depending on the presence of hemorrhage.

Pitfalls

The mural flow seen at Doppler ultrasound or contrast enhancement may overlap that of cystic ovarian tumors

Teaching Point

Most likely diagnosis when a vascular cyst or solid-appearing mass is present in premenopausal women

The wall corpus luteum cysts are usually thicker than those of follicular cysts, a distinction that can be made by ultrasound.

Hemorrhagic corpus luteum cysts may appear similar to the hemorrhagic cysts of endometriosis; on MRI, the older blood products within the more persistent endometriomas are more likely to produce the imaging finding of hemosiderin that shows low intensity in T2W images.

Case 6.4

Brief Case Summary

A 13 week pregnant woman presents with upper quadrant abdominal pain.

Imaging Findings

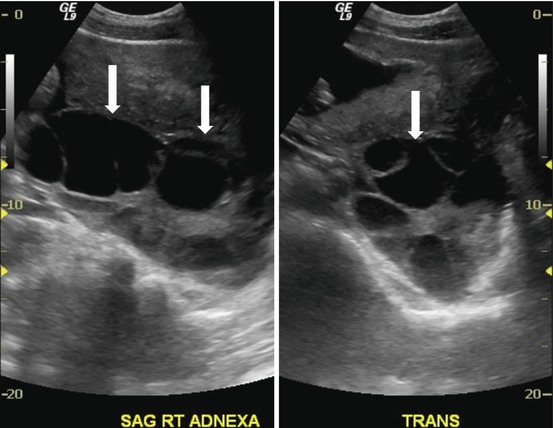

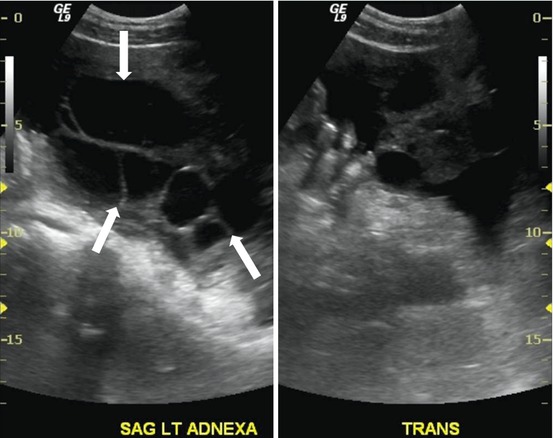

Transverse and sagittal transabdominal ultrasounds show bilateral enlarged multicystic ovaries (Figs. 6.9 and 6.10).

Fig. 6.9

Transverse transabdominal ultrasound shows bilateral enlarged multicystic ovaries (arrows)

Fig. 6.10

Sagittal transabdominal ultrasound shows bilateral enlarged multicystic ovaries (arrows)

Differential Diagnosis

Ovarian epithelial neoplasms, Luteoma of pregnancy, polycystic ovarian disease

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Theca-lutein cysts

Theca lutein cysts are associated with disorders resulting in high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) and are rarely seen in singleton pregnancies. Theses cysts may appear in patients with gestational trophoblastic disease, multiple gestations, and those undergoing infertility treatments that involve administration of ovarian stimulation agents. Theca-lutein cysts are usually asymptomatic. Abdominal pain if hemorrhage, rupture or torsion occurs.

On US, theca lutein cysts manifest as anechoic and multiloculated ovarian cysts in bilaterally enlarged ovaries. There may be thin intervening septations but no solid nodularity or papillary excrescences. The cysts may contain low level echoes if hemorrhage is present. MR findings mirror those on US and the cysts are simple T2 hyperintense lesions with possible thin internal septations. The central ovarian stroma may appear solid and a “spoke-wheel” appearance of the multiple cysts has been described.

Theca lutein cysts develop with complete hydatiform moles in approximately 14–30 % of cases. A uterus with a distended endometrium containing echogenic tissue is diagnostic. Partial molar pregnancies and complete molar pregnancies in the first trimester are not likely to be associated with theca lutein cysts as the β-hCG levels are relatively low.

Pitfalls

Misdiagnosis can result in unnecessary surgical removal of ovaries for suspected ovarian neoplasm

Teaching Point

Presence of theca lutein cysts must be considered before ovarian neoplasm in the setting of a positive β-hCG or history of ovarian stimulation.

They may be distinguished from bilateral ovarian carcinoma by the absence of solid-tissue components or papillary excrescences.

May have hypervascular central uterine mass if associated with molar pregnancy.

Typical regress after causative factor is removed.

Case 6.5

Brief Case Summary:

27 year old female with infertility.

Imaging Findings

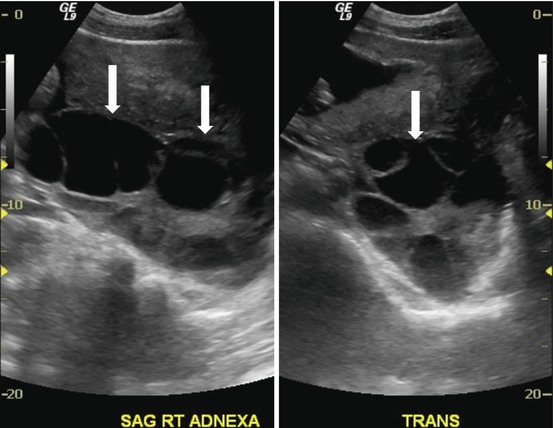

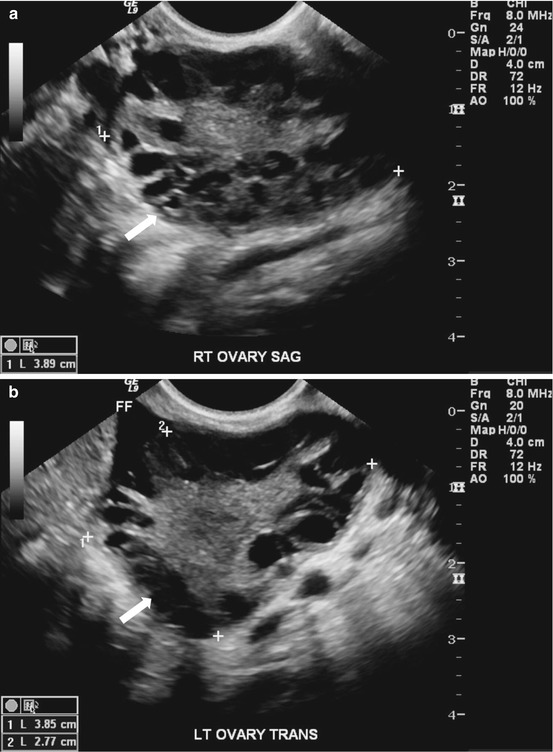

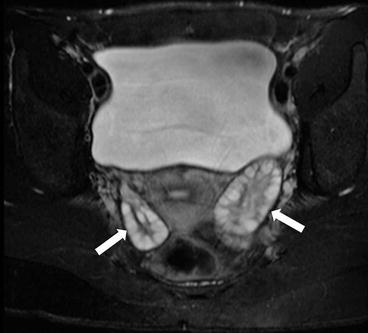

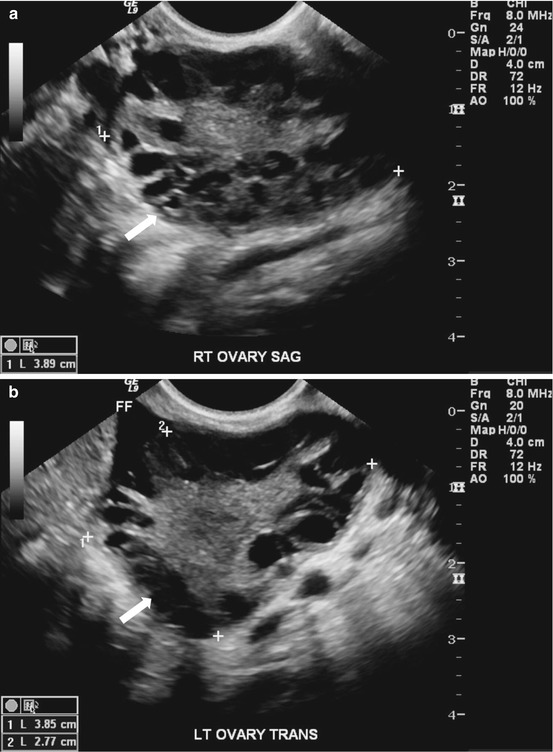

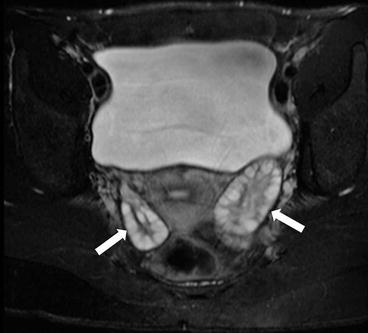

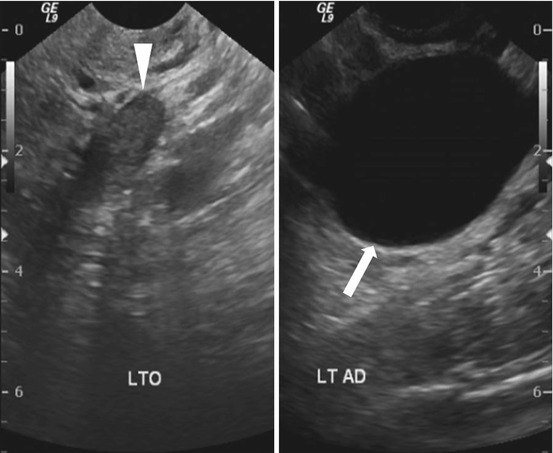

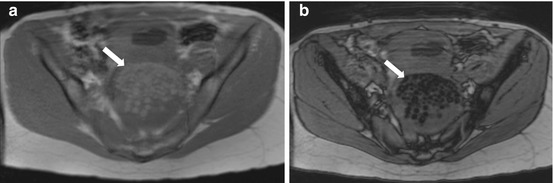

Gray scale US images of the adnexa demonstrate the presence of enlarged ovaries containing multiple peripherally oriented follicles (Fig. 6.11a, b). Axial T2 weighted MR image replicates the ultrasound findings with enlarged ovaries containing multiple peripheral follicles (Fig. 6.12).

Fig. 6.11

(a, b). Gray scale US images of the adnexa demonstrate the presence of enlarged ovaries (arrow) containing multiple peripherally oriented follicles

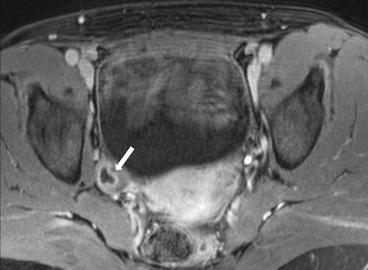

Fig. 6.12

Axial T2 weighted MR image replicates the ultrasound findings with enlarged ovaries (arrow) containing multiple peripheral follicles

Differential Diagnosis

Polycystic ovaries, ovarian torsion, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, theca-lutein cysts.

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Polycystic ovaries

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS, also known as Stein-Lenthal syndrome) represents the most common endocrine abnormality among women of reproductive age, with an incidence of approximately 5–10 %. The current diagnostic criteria for PCOS (Rotterdam criteria) involves having two of the following three conditions: (1) clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism, (2) oligo or anovulation and (3) polycystic ovaries by ultrasound. Clinically, patients often present with signs of hirsutism and irregular menstrual bleeding. In addition, patients are often overweight and have at an increased risk for hypertension, insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus and hyperlipidemia. There may also be an increased risk for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

The goal of transvaginal ultrasound is to diagnose the presence of polycystic ovaries as part of the clinical workup, though patients with normal ovaries may still have PCOS. The presence of an enlarged ovary (with volume exceeding 10 cm3) and/or ovaries with 12 or more follicles measuring 2–9 mm in diameter is sufficient for the diagnosis of polycystic ovaries on imaging. Ovarian volumes may be estimated via the simplified formula for an ellipsoid: 0.5 x length x width x thickness of the ovary. The presence of multiple follicles has been classically termed the “string of pearls” sign, though adherence to a strict objective measurement is advocated. If ultrasound remains inconclusive, MR imaging may be performed. Findings on MRI reflect the sonographic criteria, with enlarged ovaries containing multiple subcentimeter follicles, which are hyperintense on T2 weighted images. The background ovarian stroma is generally of low signal on T2 weighted images.

The imaging findings can corroborate known or clinically suspected PCOS, however, the presence of normal ovaries does not exclude the syndrome. On the other hand, the presence of polycystic ovaries is not diagnostic of PCOS. Ultrasound may also be used to monitor ovarian volumes in patients with known PCOS being treated with ovulation induction agents, with decreased volumes on serial studies potentially predictive of improved fertility outcomes.

Pitfalls

Enlarged ovaries may also be seen with other entities, including ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and ovarian torsion. OHSS is most often seen in the setting of in-vitro fertilization and demonstrates variable sized cysts associated with signs of third spacing including ascites, pleural effusions. Torsion presents with pelvic pain with ultrasound demonstrating an enlarged ovary with a heterogeneous echotexture, peripherally displaced follicles and variable absence of flow. Theca-lutein cysts are typically seen in the setting of gestational trophoblastic disease and demonstrate multiple enlarged cysts on sonographic evaluation.

Teaching Points

1.

Polycystic ovaries are enlarged ovaries with volume exceeding 10 cm3 and/or ovaries with 12 or more follicles measuring 2–9 mm in diameter.

2.

The current diagnostic criteria for PCOS (Rotterdam criteria) involves having two of the following three conditions: (1) clinical or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism, (2) oligo or anovulation and (3) polycystic ovaries by ultrasound. Thus, the presence of normal ovaries by ultrasound does not exclude the presence of PCOS.

3.

A combination of the clinical history and size of the follicles can allow confident differentiation from ovarian torsion, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and theca-lutein cysts.

Case 6.6

Brief Case Summary

35 year-old female with left adnexal mass

Imaging Findings

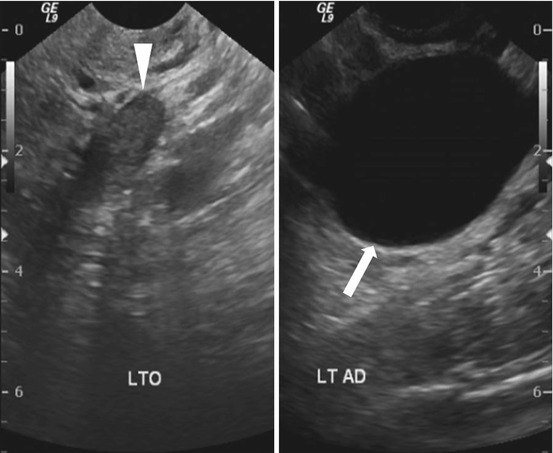

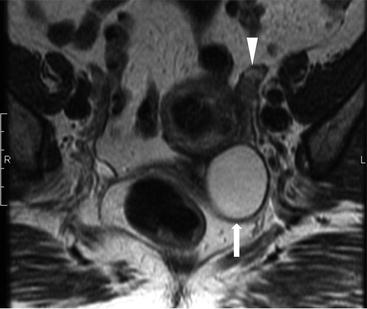

Transvaginal ultrasound (Fig. 6.13) demonstrates a normal appearing left ovary (arrowhead) and a simple cystic lesion adjacent to the ovary (arrow). Axial T2W MR image (Fig. 6.14) show a simple extraovarian cystic lesion in the left adnexa (arrow) and a normal left ovary (arrowhead).

Fig. 6.13

Transvaginal ultrasound demonstrates a normal appearing left ovary (arrowhead) and a simple cystic lesion adjacent to the ovary (arrow)

Fig. 6.14

Axial T2W MR image show a simple extraovarian cystic lesion in the left adnexa (arrow) and a normal left ovary (arrowhead)

Differential Diagnosis

Eccentric functional ovarian cysts, Peritoneal inclusion cysts, Hydrosalpinx

Diagnosis and Discussion:

Paraovarian cyst

Paraovarian cysts arise from the broad ligament, typically from mesothelium of the peritoneum or paramesonephric elements and are covered by a single layer of cells. They account for approximately 10–20 % of all adnexal masses.

Paraovarian cysts are located adjacent to but not originating from ipsilateral normal ovary. Differentiation between ovarian cysts and paraovarian cysts can be challenging but clear separation between the ovary and normal ovary is helpful in the diagnosis of paraovarian cysts. They are anechoic lesions of variable size, up to 20 cm in diameter and can be single or multicystic or unilateral or bilateral.

Malignant transformation has been reported in 2–3 % of paraovarian cysts and the presence of papillary projections growing from cyst wall are suspicious features.

Pitfalls

Clear separation between the ovary and the cystic lesion is helpful in differentiating a paraovarian cyst from an ovarian cyst. An oval configuration of a hydrosalpinx can be confused with a paraovarian cyst. An MR of the pelvis can help in differentiating these diagnoses.

Teaching Point

Dynamic evaluation with transvaginal ultrasound can show movement of cyst relative to other structures separate from the ovary. MR of the pelvis is helpful in ambiguous cases.

Case 6.7

Brief Case Summary

35 year-old female with cyclical pelvic pain.

Imaging Findings

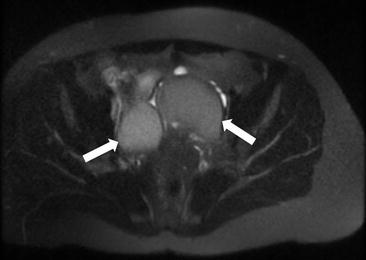

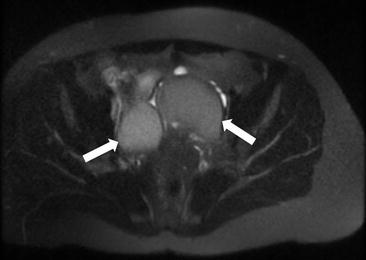

Axial T1 with fat saturation image of the pelvis (arrows, Fig. 6.15) demonstrates bilateral ovarian T1 hyperintense masses (arrows) which are less hyperintense on the T2 weighted images (arrows, Fig. 6.16) demonstrating the “T2 shading” sign.

Fig. 6.15

Axial T1 with fat saturation image of the pelvis (arrows) demonstrates bilateral ovarian T1 hyperintense masses (arrows)

Fig. 6.16

T2 weighted images (arrows) demonstrating the “T2 shading” sign

Differential Diagnosis

Hemorrhagic cysts, dermoid cysts, tubo-ovarian abscess, mucinous tumours.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside the uterus. It occurs as small implants or cystic lesions called endometriomas on the serosal and peritoneal surfaces of the abdomen. The ovary is the most commonly involved structure, followed by the pelvic peritoneum. Extra-abdominal locations have also been described, the most frequent being the lungs and the central nervous system. The disease is more prevalent in childbearing age. It is diagnosed in 17–50 % of patients investigated for infertility and in 5–18 % of those with pelvic pain.

The etiopathogenesis is still controversial. The most accepted hypothesis is retrograde menstruation, with less popular theories being direct implantation after uterine surgical procedures and hematogenous dissemination.

A woman of childbearing age with chronic pelvic pain which may be cyclical in nature or a woman who presents with infertility must be evaluated for the presence of endometriosis given the morbidity associated with delayed diagnosis. Adhesions can lead to bowel obstruction. Patients can also present with extrabdominal manifestations which include catamenial pneumothorax or hemoptysis and recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage.

The pathological lesions include implants, endometriotic cysts and adhesions. Implants can range from a few millimeters up to 2 cm. Endometriotic cysts, also known as “chocolate cysts”, result from repeated hemorrhages in a deep implant, almost always in the ovaries. Imaging is less useful than diagnostic laparoscopy for diagnosis of this condition as there is no relation between the size of the implants and the nature and severity of the symptoms; small implants are often missed, which nonetheless may cause debilitating pain. Moreover, adhesions cannot be imaged but can be seen in a diagnostic laparoscopy.

Ultrasound, often the first modality to image a woman with pelvic pain, often detects the larger endometriomas, but is insensitive for the detection of implants and adhesions. The classic sonographic description of an endometrioma is a unilocular adnexal cystic lesion separate from the ovary with angular margins and homogenous low-level internal echoes. The lesions are often multiple and bilateral. The distribution pattern of the internal echoes has been termed as ‘shading’, which is a graduated change of increasing echogenicity from the non-dependent to the dependent area. Rarely, layering with fluid-fluid level may be seen. Echogenic foci may be noted in the wall of the endometrioma, hypothesised to be cholesterol resulting from breakdown of cell membranes. Mural nodules may be noted, which if vascular, should raise the suspicion of a secondary malignancy.

CT is not useful as a screening or diagnostic modality and findings are usually incidentally noted in the imaging workup of abdominal or pelvic pain. Mixed density adnexal masses, soft tissue nodules in the anterior abdominal wall, and adhesive bowel obstruction may be evident.

MRI is the imaging modality of choice in the workup of suspected endometriosis. T1 and T2 weighted sequences, with fat suppressed T1 sequence form the mainstay of the imaging protocol. Contrast imaging is not routinely required; it is performed in the evaluation of a mural nodule for malignancy, where subtraction imaging is useful.

MRI findings may be pathognomonic. The implants are hyperintense on T1 fat suppressed sequence. Endometriotic cysts exhibit signal characteristics consistent with hemorrhage, frequently hyperintense on both T1 and T2. “The T2 shading sign” is visualized on T2 sequence whereby the T1 hyperintense endometriomas show T2 shortening due to high concentration of protein and hemorrhage from recurrent hemorrhage. A T2 dark spot sign is more specific and is defined as discrete, well-defined markedly hypointense focus within the adnexal lesion on T2-weighted images. Hematosalphinx can be seen. Hemorrhagic foci and areas of scarring are noted in the rectovaginal septum, uterosacral ligaments and the pelvic floor muscles, seen as T2 hypointense foci. Distortion of normal anatomy is often seen with posterior displacement of the uterus and ovaries, angulation of bowel loops, and elevation of the posterior vaginal fornix. Rectal strictures may form and bladder or ureteric involvement can result in hydronephrosis.

Treatment is dependent on the desire for future fertility, stage of disease, symptoms and age. Medical management is reserved for the early stages with analgesics and hormonal therapy to suppress the cyclical hemorrhage. MRI is useful for assessment of treatment response. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis can be performed in case of bowel symptoms. If fertility is not desired, hysterectomy and bilateral salphingo-oopherectomy with attempt at excision of all implants are made.

Pitfalls

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts may mimic endometriomas; shading and a T2 dark spot are useful signs suggesting recurrent hemorrhage in an endometrioma, which are usually absent in the hemorrhagic cysts. Occasionally a 6 week follow up may be needed which will reveal change in morphology in a hemorrhagic cyst with retractile clot formation. A tubo-ovarian abscess, a mimic on ultrasound, can easily be distinguished clinically from endometrioma. Enhancing mural nodule, rapid growth of the endometrioma and disappearance of the T2 shading can portend a malignant change.

Teaching Points

1.

Endometriosis is a disease of the young reproductive age group.

2.

Diagnostic laparoscopy is the mainstay of diagnosis although imaging plays a crucial role in detection of endometriomas where MRI is the modality of choice.

3.

Classic signs in US for an endometrioma are a cystic adnexal lesion, often multiple and bilateral, with diffuse low level internal echoes, hyperechoic wall foci and absence of neoplastic features.

4.

Classic features in MRI for an endometrioma include T1 hyperintense adnexal cysts which have the “T2 shading sign” and “T2 dark spots”.

Case 6.8

Brief Case Summary

33 year old female with an acute pelvic pain

Imaging Findings

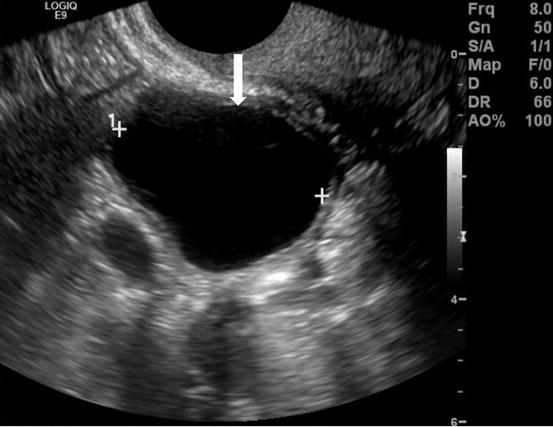

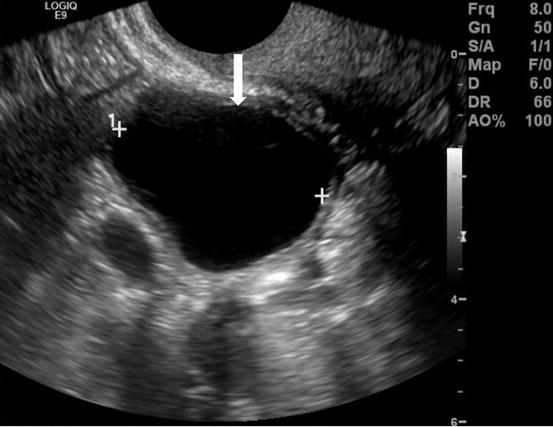

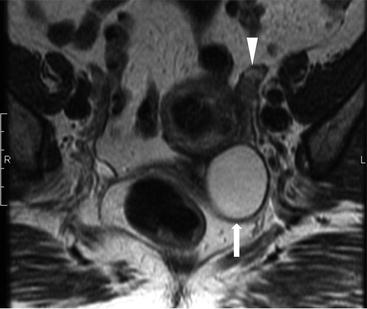

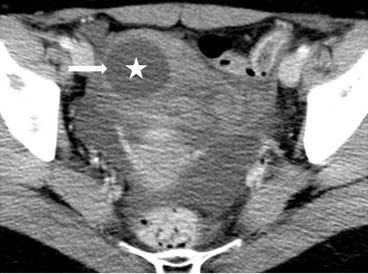

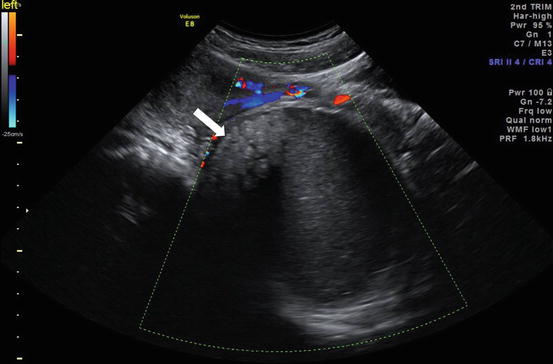

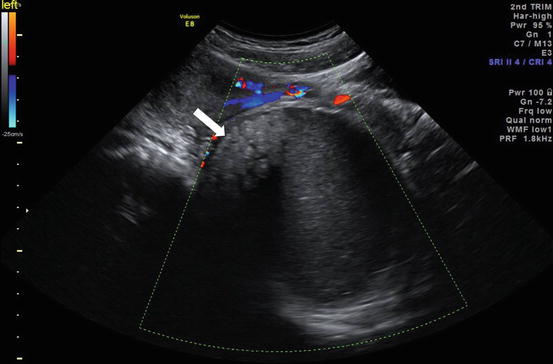

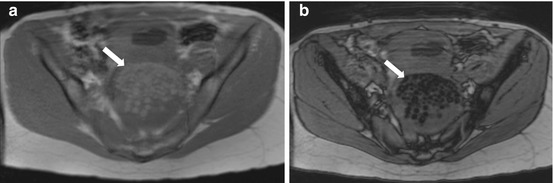

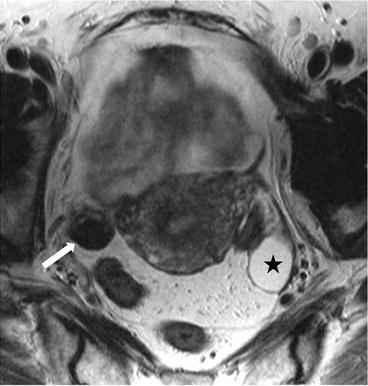

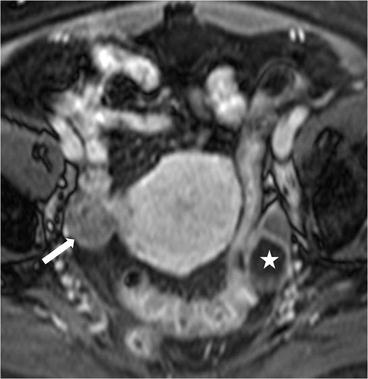

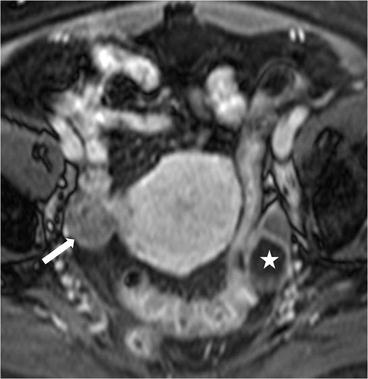

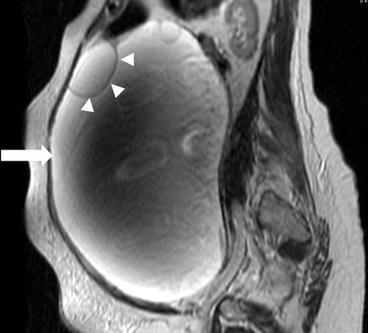

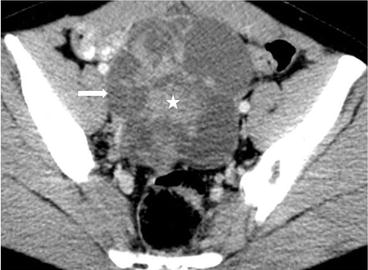

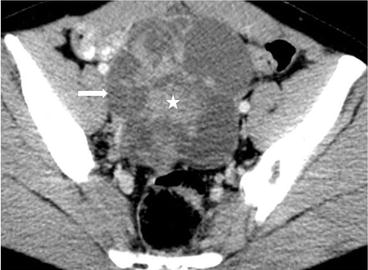

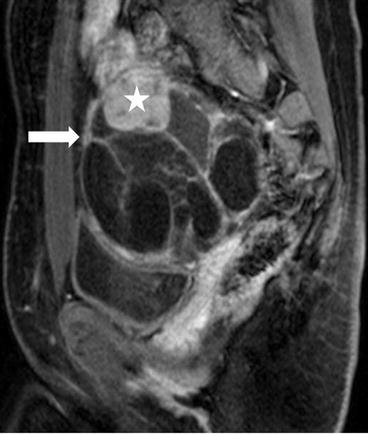

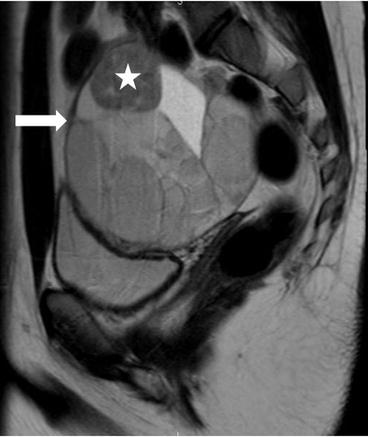

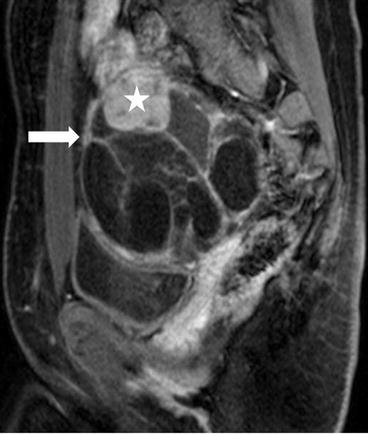

On CT (Fig. 6.17), there is an enlarged left ovary measuring 7.6 × 5.7 cm (arrow) containing a 3.6 cm cyst (asterisk) and follicles that is located to the right of midline, likely representing a torsed ovary. On an axial T2 weighted image (Fig. 6.18), a 8.3 × 6.1 × 6.3 cm cystic and solid adnexal lesion (arrow) superior to the bladder and anterior to the uterus but separate from the uterus is seen and contains multiple peripheral foci of T2 hyperintensity with a dominant 3.6 cm T2 hyperintense lesion (asterisk). On US with color Doppler (Fig. 6.19), the left ovary is enlarged with a twisted pedicle. Several follicles are seen in the ovary with a reticulated pattern (asterisk).

Fig. 6.17

CT showing an enlarged left ovary (arrow) containing a cyst (asterisk) and follicles that is located to the right of midline, likely representing a torsed ovary

Fig. 6.18

Axial T2 weighted image showing a cystic and solid adnexal lesion (arrow) superior to the bladder and anterior to the uterus but separate from the uterus is seen and contains multiple peripheral foci of T2 hyperintensity with a dominant T2 hyperintense lesion (asterisk)

Fig. 6.19

US with color Doppler showing an enlarged left ovary (arrow) and is enlarged with a twisted pedicle. Several follicles are seen in the ovary with a reticulated pattern (asterisk)

Differential Diagnosis

Acute appendicitis, ureteric calculus, diverticulitis, colitis, mesenteric adenitis, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, ruptured ovarian cyst, infarcting broad ligament fibroid, ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, and endometriosis.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Ovarian torsion is the fifth most common gynecological emergency with an estimated prevalence of 2.7 % and 10–20 % cases occur during pregnancy. Ovarian torsion is frequently associated with ovarian stimulation treatment for IVF or ovarian masses. The most common lesion associated with a torsed ovary is a physiologic cyst, accounting for 17 % of lesions, and the most common tumor associated with a torsed ovary is a dermoid, accounting for 17 %. Ovarian torsion is defined as complete or partial rotation of the ovarian vascular pedicle on its long axis. Early and accurate diagnosis must be made to avoid interruption of venous and arterial flow which may lead to edema, ischemia and necrosis of ovary. If untreated, then peritonitis and death may ultimately result. Unfortunately, the clinical symptoms of ovarian torsion lack specificity and is often initially misdiagnosed as other acute abdominal diseases, and the rate of misdiagnosis varies from 23–66 %.

US is typically the first imaging modality and imaging features include an enlarged ovary, ovarian mass, free fluid, follicles at the periphery of an enlarged ovary, thickening of a cyst wall, and a twisted pedicle. The common finding found in 74 % cases is a unilaterally enlarged ovary (dimension more than 4.0 cm or volume greater than 20 cm3 in a postmenopausal woman) with central afollicular stroma and multiple uniform 8–12-mm peripheral follicles. On Doppler US images in 35–93 % of patients with ovarian torsion, an abnormal venous blood flow is detected however altered arterial blood flow may not be seen. Additionally, color Doppler is helpful in looking for a “whirlpool sign” which denotes the twisted pedicle vessels which is the most specific feature of ovarian torsion. This sign also can be optimally showed on multiplanar CT and MRI images, especially after contrast administration. On enhanced images, heterogeneous minimal or absent enhancement of ovary may be identified due to ovarian ischemia to infarction. Besides displaying the above signs, CT and MRI can also demonstrate subacute ovarian hematoma and abnormal or absent ovarian enhancement. Subacute hemorrhage is best detected on unenhanced CT as an ovarian cyst with a layering hematocrit level or an ovarian high-density intraparenchymal hematoma, and on fat saturation T1-weighted MR images as a hematoma with hyperintense rim within an enlarged ovary.

Pitfalls

Although twisting of the ovarian pedicle is a specific sign of ovary torsion, it is identified in less than one-third of patients on CT or MRI. Other signs such as enlarged ovary with multiple follicles and abnormal enhancement, are not specific and can be seen in many other female pelvic diseases. On CT, abnormal enhancement of a solid enlarged ovary can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from a nonenhancing cyst as well as an infarcted broad ligament fibroid. The prevalence of a normal ipsilateral ovary can aid to identify an infarcted fibroid. Some other pelvic diseases presenting as an enlarged ovarian or adnexal mass combined with acute pelvic pain can be confused with ovarian torsion, such as ectopic pregnancy, hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst, and hypervascular nonepithelial primary ovarian tumors. The β-HCG test and enhanced CT or MRI scan may aid in the differential diagnosis. Polycystic ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome presents as massively enlarged ovaries which may also mimic ovarian torsion. The bilaterally enlarged ovaries and the clinical information with ovarian hyperstimulation are helpful in differentiating the two cases.

Teaching Point

1.

A unilaterally enlarged ovary with central afollicular stroma and multiple uniform peripheral follicles is the most common sign of ovarian torsion and the “whirlpool sign” is the most specific feature.

2.

Accurate and early detection of a torsed ovary can prevent ischemia and infarction of the ovary. CT and MRI images can aid to display the twisted pedicle vessels, abnormal blood supply of ovary, and subacute ovarian hematoma.

3.

Ovarian cysts and dermoids are commonly seen lesions associated with ovarian torsion.

Case 6.9

Brief Case Summary

42 year old woman with fullness in pelvis.

Imaging Findings

Color Doppler ultrasound (Fig. 6.20) image shows a large well defined heterogeneous lesion posterior to the uterus with numerous floating echogenic spherical globules.

Fig. 6.20

Color Doppler ultrasound image shows a large well defined heterogeneous lesion (arrow) posterior to the uterus with numerous floating echogenic spherical globules

Axial MRI in-phase (Fig. 6.21a) and opposed phase (Fig. 6.21b) images confirmed the presence of spherical globules within the lesion which are hyperintense on T1 weighted image (Fig. 6.21a) with signal loss on an opposed phase sequence (Fig. 6.21b) consistent with intralesional fat.

Fig. 6.21

(a) Axial MRI in-phase and (b) opposed phase images confirmed the presence of spherical globules (arrow) within the lesion which are hyperintense on in-phase T1 weighted image (a) with signal loss on an opposed phase sequence (b) consistent with intralesional fat

Differential Diagnosis

Malignant ovarian tumor.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Mature cystic ovarian teratoma.

Mature cystic teratoma is the commonest germ cell tumor, it comprises 10–15 % of ovarian neoplasms. It is a benign tumor comprised of derivatives of all 3 germ cell layers, although ectodermal elements predominate, hence the term dermoid cyst.

Sonography is usually sufficient for diagnosis showing cystic lesions with fat-fluid levels, internal echogenic elements, and calcifications. The finding of multiple intracystic echogenic globules is less common but there is sufficient literature to suggest this as a pathognomonic appearance, owing to their low density they tend to float within the cyst. In equivocal cases CT or MRI show these findings to better advantage. Almost all of the case with this appearance have been large cysts suggesting that these globules form when there is sufficient space available for them to act as a nidus with surrounding deposition of sebaceous material and fat. The fat content of these globules can be proven by in and opposed phase images on MRI, with signal dropout in opposed phase images.

Other germ cell tumors of the ovary include embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and endodermal sinus tumor.

Pitfalls

These fat globules if few in number can be confused for a mural nodule of ovarian malignancy. Application of Doppler color flow will aid in differentiation as teratoma fat globules do not show vascularity.

Teaching Point

The finding of floating lipid spherules within a large cyst is pathognomonic for a mature cystic teratoma.

Floating fat globules, no color flow on Doppler ultrasound, and loss of signal on opposed-phase MR images confirm the diagnosis of dermoid and should help in avoiding misdiagnosis.

Case 6.10

Brief Case Summary

52 years old female with clinical stage IIB clear cell adenocarcinoma of cervix.

Imaging Findings

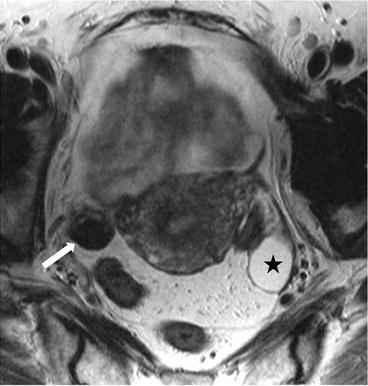

Axial T2 MR image (Fig. 6.22) demonstrates a right ovarian hypointense lesion (arrow) with homogeneous enhancement, on the axial T1 postgadolinium image (Fig. 6.23). In the left adnexa, a 2.8 cm T2 hyperintense nonenhancing lesion is seen in the ovary (asterisk) consistent with a benign cyst.

Fig. 6.22

Axial T2 MR image demonstrates a right ovarian hypointense lesion (arrow). In the left adnexa, a T2 hyperintense lesion is seen in the ovary (asterisk) consistent with a benign cyst

Fig. 6.23

Axial T1 postgadolinium image. In the left adnexa, T2 hyperintense nonenhancing lesion is seen in the ovary (asterisk) consistent with a benign cyst

Differential Diagnosis

Thecomas, fibrosed thecomas, fibrothecomas, cystadenofibroma, pedunculated uterine fibroids and broad ligament

Diagnosis and Discussion

Fibromas account for approximately 4 % of all ovarian tumors and represent the most commonly encountered subtype of sex cord-stromal tumors. They occur at all ages but are most frequently seen in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Fibromas are usually asymptomatic and typically found incidentally. They are rarely associated with hormone production, but not infrequently connected with increased ascites and elevation of CA 125 levels, although Meig’s syndrome (ascites, ovarian tumor, and pleural effusion) only occurs in a small percentage of cases. Pathologically, fibromas are of stromal derivation and have no epithelial component. They are composed of whorled fascicles of cytologically bland spindle cells forming variable amounts of collagen. Fibromas typically reveal a firm, encapsulated, chalky-white, whorled mass with smooth contour, mimicking fibroids. Some of fibromas also contain both solid and cystic (usually only a few) parts, occasionally completely cystic pattern. The appearance of ascites, increased CA 125 levels, and solid components of fibromas can make differentiation from ovarian malignant tumors difficult. Calcifications and bilaterality are seldomly observed in fibromas.

On ultrasound, solid fibromas most commonly manifest as solid hypoechoic masses. The presence of striped shadows is typical of benign fibromas, which possibly can be explained by the cellular bundles and intersecting strips of hyaline-appearing collagen and fibrous tissue. However, owning to the varying degrees of cellularity, collagen content and stromal edema, the US appearance of fibromas is variable, and hyperechoic masses with increased through-transmission may be seen. About 75 % of fibromas manifest minimal or moderate amount of color Doppler signal, but fibromas can show either no vascularity or abundant vascularization. On CT, fibromas manifest as diffuse, slightly hypoattenuating masses, with poor and delayed enhancement on CT scan, which is unlike most other solid masses. Typical fibromas demonstrate homogeneous, isointense to hypointense to uterine myometrium on T1-weighted MR images and well-circumscribed masses with low signal intensity compared with myometrium on T2-weighted images. This low signal intensity results from the abundant collagen content of the tumors. Some cases may contain scattered high-signal-intensity areas representing edema or cystic degeneration, which are more common in the larger tumors (>6 cm). A T2-hypointense capsule can also be noted in about 60 % of cases, especially the larger ones. In premenopausal women, the residual ovary can be seen on MR imaging where 54 % of the remaining ovary shows a crescent configuration along the periphery of the fibroma (i.e., the “ovarian crescent sign”), as well as the others show a preserved, normal-appearing ovoid shape, suggesting exophytic growth of the fibroma from the periphery of the ovary. To the former growth pattern, the presence of peripheral small follicles or cortical inclusion cysts can be noted on T2-weighted images, which can help in differentiation from fibroids.

Pitfalls

Some fibromas are sonographically atypical with a cystic appearance and may be confused with ovarian cystadenofibromas or mucinous cystadenomas coexisting with benign Brenner tumors. Pedunculated uterine fibroids and broad ligament fibroids frequently appear as adnexal or ovarian masses with low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, similar to fibromas. The presence of peripheral follicles and the weak enhancement help differentiate fibromas from fibroids. But in patients with a solid-appearing ovary without visible follicles, the different diagnosis might be difficult.

Teaching Point

1.

A solid, well-circumscribed ovarian mass with striped shadows on ultrasound, homogeneously hypointense on T2-weighted MR images should be highly suspicious as fibroma, especially with delayed enhancement and the presence of ascites.

2.

Compared to ultrasonography and CT, MRI is more useful to display the structural characteristics of fibroma and its relationship with remaining ovary.

3.

The presence of peripheral follicles and the weak enhancement aid in differentiating fibromas from pedunculated uterine fibroids and broad ligament fibroids.

Case 6.11

Brief Case Summary

63-year-old woman with left lower extremity deep vein thrombosis and large right ovarian mass.

Imaging Findings

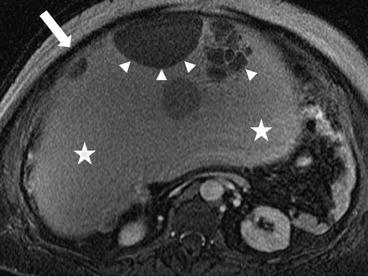

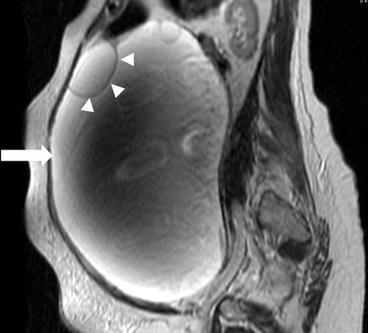

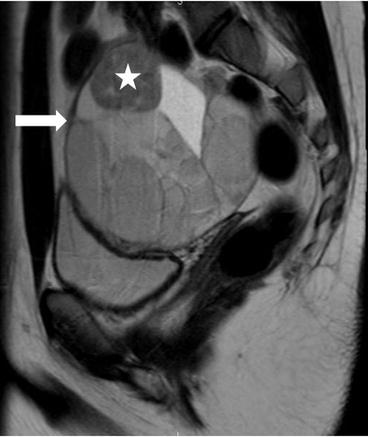

There is a 31 × 31 × 20 cm T2 hyperintense cystic lesion (Fig. 6.24, arrow) of the right ovary. This is multiloculated (arrowhead) with a predominantly large single cystic component. On a postgadolinium T1 weighted image (Fig. 6.25), the mass has a stained-glass appearance (asterisk) with areas of solid nodules (arrowheads). Dependently there is some layering sediment (filled asterisk).

Fig. 6.24

A 31 × 31 × 20 cm T2 hyperintense cystic lesion (arrow) of the right ovary. This is multiloculated (arrowhead) with a predominantly large single cystic component

Fig. 6.25

A postgadolinium T1 weighted image; the mass has a stained-glass appearance (asterisk) with areas of solid nodules (arrowheads). Dependently there is some layering sediment (filled asterisk)

Differential Diagnosis

Adenofibroma, serous cystadenoma, mucinous borderline cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenocarcinoma, cystic teratoma, endometrioma, endometrioid ovarian carcinoma, cystic metastases.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Ovarian mucinous cystadenoma is a type of epithelial ovarian tumor, accounting for approximately 80 % of mucinous ovarian tumors and 20–25 % of all benign ovarian tumors. In contrast to serous cystadenomas of the ovary, mucinous cystadenomas are less common and less likely to be bilateral with only 2–5 % of cases being bilateral. Pathologically, mucinous cystadenoma is composed of a single layer of columnar cells with abundant intracellular mucin and small basilar nuclei lining the cysts. Papillae are unusual, except in occasional examples of mucinous and seromucinous cystadenomas of endocervical-like type, which are highly papillary. Gastrointestinal differentiation is more often noted in borderline tumors and carcinomas than cystadenomas. Typical mucinous cystadenomas are large, multilocular masses with numerous smooth, thin-walled cysts containing proteinaceous or mucus and hemorrhage.

On the ultrasound, mucinous cystadenomas demonstrate low-level internal echoes with multiple thin septa. CT may demonstrate high attenuation in some loculations due to the high protein content of the mucoid material. On the MR and CT images, due to complex contents in the loculations, the tumors often present with various attenuations or signal intensities, which is called as “stained-glass appearances”. The signal intensity of mucin depends on the degree of mucin concentration. On T1-weighted images, loculations with watery mucin have lower signal intensity than loculations with thicker mucin, whereas on T2-weighted images, the loculations with watery mucin have high signal intensity whereas loculations with thicker mucin appear slightly hypointense. Contrast-enhanced images help to distinguish septal wall thickness from cysts. The presence of a thick wall or septation may suggest borderline lesions while the presence of solid components suggests carcinoma.

Pitfalls

Other cystic ovarian benign lesions and neoplasms with hemorrhage or mucus in the cystic portions broaden the differential diagnosis of mucinous cystadenoma based on imaging. As the most representative one of them, borderline mucinous cystadenoma has a multilocular appearance at MR imaging and are indistinguishable from mucinous cystadenomas. Because of overlapping appearances, serous and mucinous cystadenomas are difficult to accurately differentiate on ultrasound alone. Fortunately, T1-and T2-weighted MR images can readily discriminate the “stained glass appearance” loculations of mucinous cystadenomas from water signal loculations of serous cystasenomas. Furthermore, high-signal-intensity loculations may influence the enhancement assessment on precontrast images. Subtraction postprocessing may aid in identifying true enhancement.

Teaching Point

1.

A multilocular cystic mass of the ovary with a thin regular walls and septa, the “stained glass appearance” on MRI, and without endocystic or exocystic vegetations, should be considered to be a benign mucinous cystadenoma.

2.

Comparing with ultrasonography and CT, MRI is superior in differentiating the heterogeneity of the loculations in mucinous cystadenomas.

3.

Borderline tumor and carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis when a thick wall or septation is present.

Case 6.12

Brief Case Summary

20-year-old woman with abdominal pain.

Imaging Findings

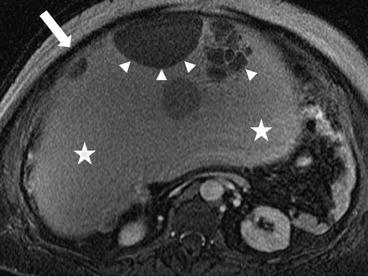

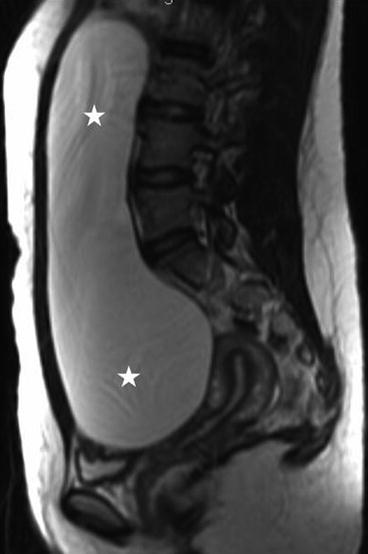

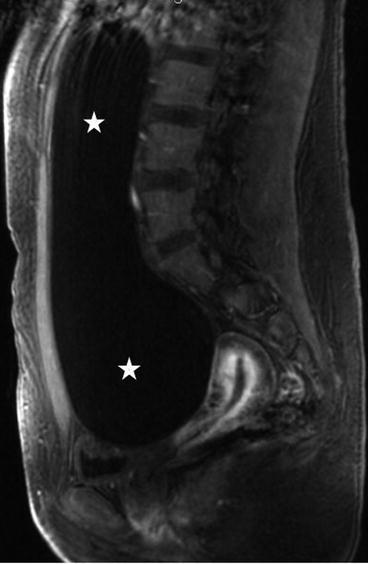

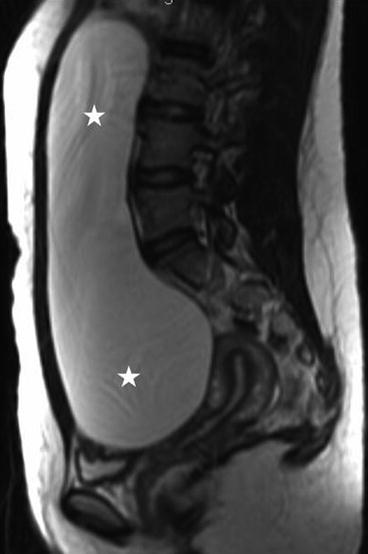

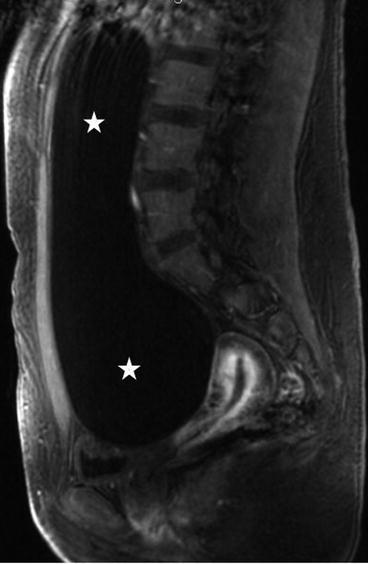

There is a large unilocular cyst that crosses the midline and extends up to approximately the liver, measuring approximately 20 cm × 5 cm. There is no evidence of wall thickening of the cyst and there are no septations.

On the sagittal T2 image (Fig. 6.26), a large T2 hyperintense cystic lesion measuring 20 × 5 cm is seen (asterisks) arising from the pelvis extending into the abdomen. On the T1 post gadolinium image with fat saturation (Fig. 6.27), no enhancement or solid enhancing components are visualized in the cystic lesion.

Fig. 6.26

Sagittal T2 image of a large T2 hyperintense cystic lesion measuring 20 × 5 cm is seen (asterisks) arising from the pelvis extending into the abdomen (asterisks)

Fig. 6.27

T1 post gadolinium image showing fat saturation, no enhancement or solid enhancing components are visualized in the cystic lesion (asterisks)

Differential Diagnosis

Ovarian functional cysts, ovarian inflammatory cystic lesions, mucinous cystadenoma

Diagnosis and Discussion

Serous cystadenoma accounts for approximately 60 % of all the serous benign ovarian neoplasms and is more common than mucinous cystadenoma. It predominantly affects women between 40 and 50 years old. Bilaterality is frequent, occurring in 12–23 % of cases. Serous cystadenomas usually appear as uni- or bilocular cystic masses. Grossly, the tumors consist of a thin-walled unilocular cyst with smooth inner and outer surfaces. Microscopically, the lining of the cyst is flat or may contain small papillary projections. Psammoma bodies (microscopic calcifications) occasionally can be seen at histologic analysis and proved on CT images.

On ultrasonography, serous cystadenomas are usually seen as an anechogenic to homogenously hypoechogenic unilocular cyst that are larger than typical functional cysts. Papillary projections are rare but tend to be thin with a regular surface forming an acute angle with the cyst wall. Some lesions may contain sonographically detectable septations. The typical CT appearance of serous cystadenoma is a thin wall cystic lesion, without soft tissue components or papillary projections. Due to the serous nature of the fluid, CT density of the cysts assume homogeneous low intensity as pure water, except for companying with high-density hemorrhage. In uncomplicated cases, serous cystadenomas show low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Hemorrhage within the cysts can be depicted as iso to hyperintense signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images. Additionally, regular thin walls, minimal septa, and small papillary projections of the tumors can be depicted better with enhanced CT or MR images.

Pitfalls

Serous and mucinous cystadenomas are the two most common types of epithelial neoplasms and have a lot of overlapping pathology, disease course, as well as imaging features. However, some features are helpful to differentiate the two types (see Table 6.1 ).

Table 6.1

Features that help differentiate serous from mucinous tumors

Tumor type | ||

|---|---|---|

Feature | Serous | Mucinous |

Clinical findings | ||

Benign ovarian tumors | 25 % | 20 % |

Malignant ovarian tumors | 50 % | 10 % |

Proportion of malignant cases | 60 % benign, 15 % low malignant potential, 25 % malignant | 80 % benign, 10–15 % low malignant potential, 5–10 % malignant |

Imaging findings | ||

Size | Smaller than mucinous tumors | Often large; may be enormous |

Wall, locule | Thin-walled cyst, usually unilocular | Multilocular, small cystic component, honeycomb-like locules |

Opacity or signal intensity of locule | Stable | Variable |

Papillary projections | Often seen | Rare |

Calcification | Psammomatous, common | Linear, rare |

Bilaterality | Frequent | Rare |

Carcinomatosis | More common | Pseudomyxoma peritonei |

Similar imaging characteristics, such as unilocular pattern, anechoic on US or low intensity on MR, thin and smooth walls, absence of papillary projections, may appear in both ovarian functional cysts and serous cystadenomas. Complex functional cysts, for example, hemorrhagic corpus luteum cyst, also make accurate diagnosis difficult. Follow-up US or further assessment of cyst walls and septa with contrast enhanced MR imaging might help. In addition, when cyst wall thickness greater than 3 mm and/or vegetations are noted, serous malignant neoplasms should be included in differential diagnosis.

Teaching Point

1.

A unilocular or bilocular cystic ovarian mass with a thin regular wall and septa, homogeneous CT attenuation or MR imaging signal intensity of the loculations, and without endocystic or exocystic vegetations, is considered to be a benign serous cystadenoma.

2.

Serous cystadenomas need to be carefully distinguished from complex functional cysts and mucinous cystadenomas based on imaging features.

3.

Owing to its relative high bilateral incidence (approximately 12–23 %), when a serous cystadenoma is suspected, it is of increased importance to evaluate the contralateral ovary.

Case 6.13

Brief Case Summary

35 year old female with complaint of bloating and gastrointestinal issues.

Imaging Findings

Axial CT (Fig. 6.28) shows a complex cystic-solid 10.5 × 10.4 × 13 cm lesion (arrow) located at right adnexal area, with irregular nodular solid enhancing component (asterisk).

Fig. 6.28

Axial CT shows a complex cystic-solid 10.5 × 10.4 × 13 cm lesion (arrow) located at right adnexal area, with irregular nodular solid enhancing component (asterisk)

Differential Diagnosis

Serous cystadenoma, serous cystadenocarcinoma, ovarian endometriosis, endometrioid tumors

Diagnosis and Discussion

Clear cell carcinoma (CCC) is a less common surface epithelial carcinoma, constituting up to 10 % of ovarian cancers and are similar to clear cell carcinomas of the endometrium, cervix, or vagina. The mean age of patients presenting with CCC is approximately 50 years. About 10 % of patients are still associated with hypercalcemia and about 25–50 % of patients are associated with endometriosis. Synchronous carcinoma of the uterus and pelvic endometriosis commonly occur with CCC. As with endometrioid tumors, nearly all clear cell tumors are invasive carcinomas. Kaku et al. reported the prognosis of CCC was despite a majority, approximately 82.6 % of patients with CCC presenting with stage I disease. Both distant organ involvement (40 %) and lymph node involvement (40 %) are frequent in patients with recurrent CCC.

CCCs are more frequently seen as unilocular smooth cystic masses associated with irregular walls, thick septa (>3 cm), solid protrusions on US, CT and MR images. The cystic masses are usually larger than 4 cm. MR is sensitive in differentiating the various cystic contents, such as protein and hemorrhage. The signal intensities of cystic contents vary from low to very high on T1WI, while high on T2WI in all cases. Both US and MR images can clearly display the solid protrusions based on superior contrast between cystic contents and solid protrusions. The solid protrusions are either single or few in number and include round, papillary and irregular shapes, with the round shape being more common. On enhanced CT and MR images, the solid parts homogeneously or heterogeneously enhance.

Pitfalls

The imaging characteristics of ovarian CCC lack specificity when compared to other cystic tumors of ovary, such as serous cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. CCCs also may be misdiagnosed as ovarian chocolate cysts.

Teaching Point

1.

CCCs are often associated with hypercalcemia, endometriosis, and endometrioid tumors.

2.

A greater than 4 cm unilocular smooth cystic mass associated with one or a few solid protrusions should raise suspicious for a CCC, but these signs lack specificity.

Case 6.14

Brief Case Summary

16-year-old woman with right ovarian mass and clinical symptoms of polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Imaging Findings

There is a complex multiloculated cystic lesion (arrow) in the right adnexa measuring 8.6 × 8.0 × 9.6 cm. A normal right ovary cannot be identified separate from this lesion. The lesion contains multiple cysts of varying sizes, some of which demonstrate intrinsic T1 signal that could represent blood or proteinaceous products (not shown). Along the superior margin of the lesion is a solid enhancing component on the postgadolinium image (Fig. 6.29, asterisk) that shows low signal intensity on T2-weighted image (Fig. 6.30, asterisk).

Fig. 6.29

T2-weighted image showing heterogenous multiloculated lesion (arrow) with low signal intensity (asterisk) and high signal intensity components

Fig. 6.30

T1 weighted Postgadolinium image showing a complex multiloculated cystic lesion (arrow) in the right adnexa measuring 8.6 × 8.0 × 9.6 cm, and a solid enhancing component along the superior margin of the lesion (asterisk)

Differential Diagnosis

Granulosa cell tumor, endometrioma, fibrothecoma, cystadenoma, and cystadenoma.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor (SLCT) of the ovary is a rare sex cord stromal tumor, accounting for less than 0.5 % of all ovarian tumors. Its histopathological characteristics are the biphasic proliferation of Sertoli and Leydig cells with varying degrees of differentiation. The prognosis of Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor is closely associated with the stage and degree of tumor differentiation. Pathologically, SLCT are divided into four subtypes: I. well- (11 %); II. intermediately- (54 %); III poorly differentiated (13 %); and IV. containing heterologous elements (22 %). The majority of SLCTs behave in a benign fashion, and 92 % of the tumors are stage I at presentation. Only 10–18 % of SLCTs with subtype III can behave in a malignant fashion. SLCTs commonly affect young females, and approximately 75 % of the patients are less than 30 years old. Most SLCTs (approximately 62.5 %) show endocrine functions (producing androgen or estrogen) and related clinical symptoms, in which virilization is the most common manifestation. In the patients with non-functional SLCTs, the higher proportions of large tumors, tumor rupture, and tumors of poor differentiation may indicate more aggressive biological behaviors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree