Table 4.1 Differential Features of Various Fibrous Lesions with Similar Radiographic Appearances | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Benign lesion of bone composed of spindle-shaped fibroblasts, arranged in a storiform pattern, with a variable admixture of multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells, and occasionally lipid-bearing xanthomatous cells, chronic inflammatory cells, and hemosiderin-laden histiocytes.

The name fibrous cortical defect is used when the lesion is confined to the cortex; if the lesion becomes large enough to extend into adjacent medullary cavity, then the term nonossifying fibroma (NOF) is used.

Age ranged from 6 to 74 years old; 30% to 40% in children.

Children of an average age of 4 years (54% of boys and 22% of girls) had a lesion involving the cortex, and majority of lesions regressed spontaneously over a period of approximately 2.5 years.

Approximately 40% lesions occur in the long bones, with the distal femur and distal and proximal tibia most commonly affected.

As many as 25% of cases involve the pelvic bones, particularly the ilium.

Majority of patients are asymptomatic, and the lesion is accidentally discovered on imaging studies performed for other reasons.

Larger lesion may cause pain that is probably secondary to microfractures or obvious pathologic fracture.

Most pathologic fractures develop through the lesions that involve more than 50% of the transverse diameter of the bone.

The vast majority of lesions are monostotic; approximately 8% of cases are polyostotic.

Polyostotic lesions may be associated with Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome, a condition comprising nonossifying fibromatosis, neurofibromas, and café-au-lait spots.

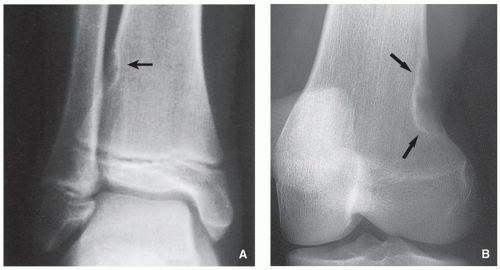

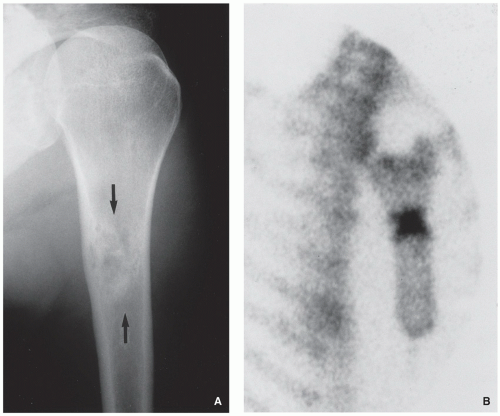

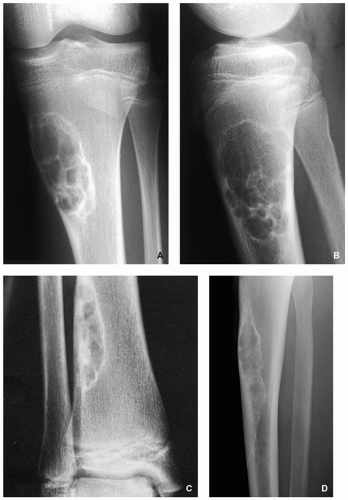

Radiography demonstrates eccentric, radiolucent lesion with sclerotic border centered within the metaphyseal or diaphyseal cortex (fibrous cortical defect) (Fig. 4.1), or extending into the adjacent medullary cavity (NOF) (Figs. 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4); it may exhibits prominent trabeculations (see Fig. 4.2B).

Scintigraphy shows minimal to mildly increased activity.

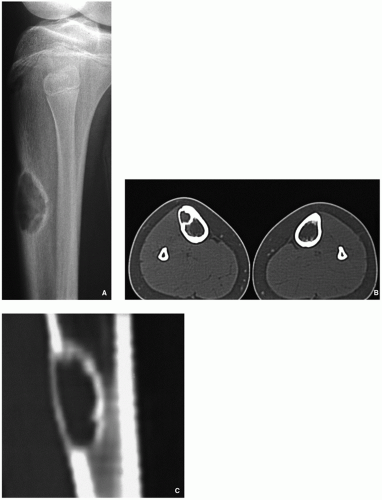

Computed tomography demonstrates to better advantage the cortical thinning and medullary involvement (Fig. 4.5) and may delineate early pathologic fracture more precisely.

Magnetic resonance imaging shows intermediate-to-low signal intensity on T1-weighted and intermediate-to-high signal intensity on T2-weighted and other water-sensitive sequences. After intravenous administration of gadolinium, the lesion exhibits a hyperintense border and signal enhancement (Fig. 4.6).

Central or more often eccentric, well-circumscribed lesion with sclerotic and sometimes scalloped borders.

The lesions are reddish-brown and frequently exhibit areas that are soft and yellow (Fig. 4.7A).

The overlying cortex is thinned out and may be eroded (Fig. 4.7B).

FIGURE 4.2 Radiography of nonossifying fibroma. (A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral radiographs of a 12-year-old girl, show a large elliptical lobulated lesion eccentrically located in the proximal tibia exhibiting well-defined sclerotic border and prominent trabeculations. (C) Eccentrically located lesion in the distal tibia of an asymptomatic 15-year-old boy exhibits a slightly scalloped sclerotic border. (D) In another patient, an 8-year-old boy, lateral radiograph of the leg shows a long radiolucent lesion with sclerotic border affecting the anterior cortex of the proximal tibia and extending into the medullary cavity of bone, similar in appearance to osteofibrous dysplasia (see Figs. 4.39 and 4.40). |

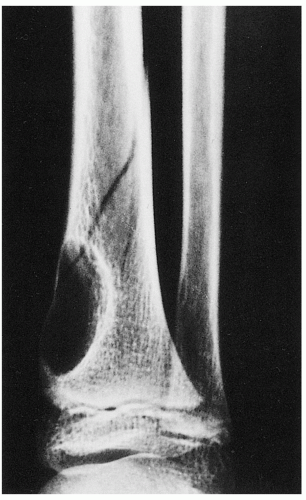

FIGURE 4.3 Radiography of nonossifying fibroma. A large radiolucent lesion in the distal tibia of a 10-year-old boy is complicated by a pathologic fracture. |

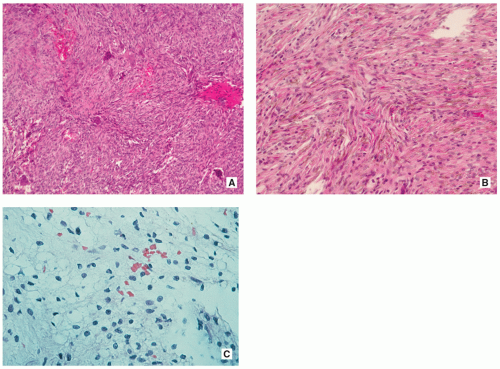

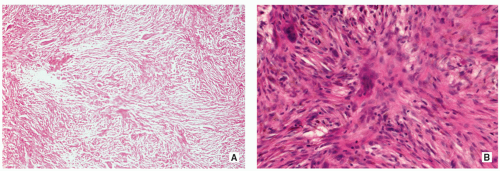

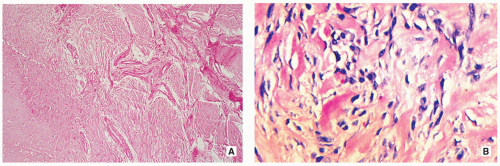

Stroma of spindle-shaped fibroblasts, arranged, at least focally, in a whorled, storiform pattern, with scattered variable number of small, multinucleated, osteoclast-type giant cells (Figs. 4.8, 4.9 and 4.10).

Foam (xanthoma) cells, with small, dark nuclei, are frequently but not always found, interspersed among the stromal cells individually or in small clusters (see Fig. 4.8C).

Siderin-containing macrophages may be present (see Fig. 4.10A).

Scattered inflammatory cells, mainly lymphocytes, are present (see Fig. 4.9B).

Small stromal hemorrhages and hemosiderin may be present.

Excellent.

Many lesions undergo spontaneous healing.

Asymptomatic lesions usually do not need surgical intervention.

Painful larger lesions or those that exhibit an impending or established pathologic fracture are adequately treated by curettage and bone grafting.

A benign neoplasm, which may develop within the bone, subcutaneous tissue, deep soft tissue, or in the parenchymal organs, composed of mixture of fibroblastic and histiocytic cells arranged in sheets of short fascicles and accompanied by inflammatory cells, foam cells, and siderophages.

When located in the skin is also called dermatofibroma.

May occur in any age, but adults over 25 years are most commonly affected.

In the skeletal system—articular end of long bone, flat bones (pelvis, ribs).

In the soft tissues—the lower limb and the head and neck region are the most common sites; most cases involve skin and subcutaneous tissue, but a few cases were described in muscle, mesentery, trachea, and kidney.

In the bones, presents as a painful mass.

In the skin and soft tissues, most cases present as solitary, painless, and slowly enlarging mass.

May occur after minor trauma or insect bites.

Radiography shows well-defined radiolucent lesion with sclerotic borders, similar in appearance to NOF, occasionally exhibiting some degree of expansion (Fig. 4.11).

Scintigraphy shows moderately increased uptake of radiopharmaceutical tracer (Fig. 4.12).

Magnetic resonance imaging features are identical to those of NOF and show the lesion to be of intermediate signal intensity and isointense with the muscles on T1-weighted images and of high signal intensity on water-sensitive sequences.

Osseous lesions similar to NOFs.

Cutaneous lesions are elevated or pedunculated, measuring from a few millimeters to few centimeters.

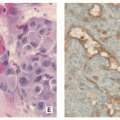

Osseous lesions similar to NOFs but storiform pattern more prominent (Figs. 4.13 and 4.14).

Cutaneous lesions consist of nodular spindle cell proliferation involving the dermis and occasionally subcutis.

Borders of the tumor are sharply demarcated and typically interdigitate with dermal collagen (“collagen trapping”).

Tumor cells are cytologically bland and spindle shaped with elongated or plump vesicular nuclei and eosinophilic, ill-defined cytoplasm.

There is no nuclear pleomorphism or hyperchromasia; mitoses may be seen.

Stroma may show myxoid changes or hyalinization, and some xanthoma-like cells.

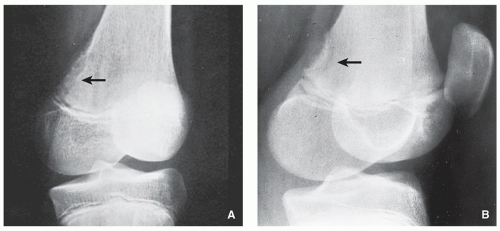

FIGURE 4.11 Radiography of benign fibrous histiocytoma. (A) A 37-year-old man presented with occasional pain in the right knee. An oblique radiograph of the knee shows a lobulated radiolucent lesion with well-defined sclerotic border, located eccentrically in the proximal tibia. (B) A 16-year-old boy presented with a painful tibial lesion, which on radiographic examination looked like a NOF. On the excision biopsy, the lesion was more consistent with benign fibrous histiocytoma (see Fig. 4.13). (C) A 42-year-old woman presented with left hip pain. The radiograph shows a well-defined lesion with sclerotic border located in the supra-acetabular portion of the ilium, similar in appearance to NOF. The excision biopsy was more consistent with benign fibrous histiocytoma.

Deep fibrous histiocytomas usually are similar to cutaneous form but show more prominent storiform pattern and fewer secondary elements like xanthoma cells.

Positive for factor XIIIa, desmin, and CD34.

May recur locally if not incompletely excised.

Tumor-like fibrous proliferation of the periosteum, with striking predilection for the posteromedial cortex of the distal femur.

Age between 12 and 20 years.

Predominantly the boys are affected.

Posteromedial cortex of the medial femoral condyle at linea aspera.

Asymptomatic lesion discovered by serendipity, usually through the imaging studies done for trauma.

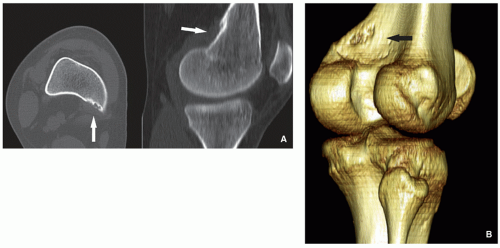

Radiography and computed tomography shows cortical irregularity or saucer-like radiolucent defect with sclerosis at its base (Figs. 4.15 and 4.16). May mimic aggressive or malignant tumor-like osteosarcoma or Ewing sarcoma.

Magnetic resonance imaging shows the lesion to be hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted and other water-sensitive sequences.

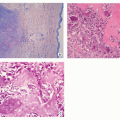

Fibroblastic spindle cells that produce a large amount of collagen. Large areas of hyalinization and fibrocartilage and small fragments of bone may be scattered within fibrous tissue (Fig. 4.17).

Excellent. Spontaneous regression in majority of cases.

Benign medullary fibro-osseous lesion, which may involve one (monostotic form) or more (polyostotic form) bones, characterized by the replacement of normal lamellar and cancellous bone by abnormal fibrous tissue containing trabeculae of immature woven bone.

Children and adults.

No gender predilection.

Monostotic form most common (70% to 80%).

Gnathic (jaw) bones most common.

Long bones are more often affected in women.

Ribs and skull are favored sites for men.

In monostotic form, about 35% involve the skull, 33% the tibia and femur, and 20% the ribs.

In polyostotic form, the femur, pelvic bones, and tibia are most commonly affected.

Polyostotic form can be confined to one extremity or one side of the body or be diffuse.

Polyostotic form often manifest earlier in life than the monostotic form.

The condition is often asymptomatic, but pain and pathologic fractures may be part of the clinical spectrum.

Oncogenic osteomalacia may be associated.

Polyostotic form may manifest as McCune-Albright syndrome, the condition marked by skin pigmentation (caféau-lait spots) and variety of endocrine abnormalities.

If polyostotic form is associated with formation of soft-tissue myxomas, the condition is known as Mazabraud syndrome.

If there is cartilage deposition within the lesion, the condition is known as fibrocartilaginous dysplasia (see below).

The various amount of bone in the fibrous tissue that replaces the cancellous bone imparts a radiographic picture that ranges from radiolucency to radiodensity of the lesion (Fig. 4.18).

More common radiographic presentation is a radiolucent lesion exhibiting a ground-glass, milky, or smoky appearance (see Fig. 4.18A).

In the appendicular skeleton, the margins are usually well defined and surrounded by a rim of sclerotic bone (rind sign) (Fig. 4.19), but some lesions, including those in the craniofacial bones, may have indistinct borders.

Cortex is usually thinned out (see Fig. 4.18A).

“Shepherd’s crook” deformity of the femur is a characteristic feature (Fig. 4.20).

Skull lesions affect primarily the base, causing thickening and sclerosis of the sphenoid wings, sella, and the vertical portion of the frontal bones; less common the vault of the skull is affected (Fig. 4.21).

Scintigraphy shows moderate to markedly increased activity of radiopharmaceutical agent (Figs. 4.22 and 4.23).

CT accurately delineates the extent of bone involvement, with Hounsfield units in the range of between 70 and 400 HU (Figs. 4.24, 4.25, 4.26, 4.27 and 4.28, see also Fig. 4.21).

MRI shows the lesion to be of intermediate to low signal intensity on T1-weighed sequences and of high signal on T2-weighting and other water-sensitive sequences (Figs. 4.29, 4.30 and 4.31). There is enhancement of the lesion after intravenous administration of gadolinium.

In Mazabraud syndrome, MRI shows soft-tissue masses of intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and homogenously bright on T2 weighting, representing myxomas (Fig. 4.32).

Well-circumscribed white-tan lesion of gritty and leatherlike consistency (Fig. 4.33).

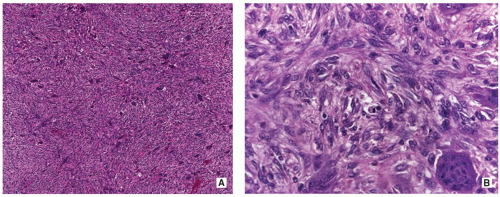

Cellular fibrous tissue is surrounding the irregular, curvilinear bone trabeculae (Fig. 4.34).

The bone trabeculae are discontinuous and are composed of woven bone that is formed directly from the spindle cells with no osteoblastic rimming (“naked trabeculae”) (Figs. 4.35 and 4.36).

In craniofacial tumors, the abnormal bone tends to fuse with the surrounding host cancellous bone.

The spindle cells may be arranged in a storiform pattern and may be associated with collection of foamy macrophages mimicking xanthoma or fibroxanthoma.

Collagen fibers (Sharpey-like fibers) are frequently seen extending from the fibrous tissue into the immature woven bone trabeculae (see Fig. 4.35B).

Cementicle-like pattern, reminiscent of cementifying fibroma of the jaw, is occasionally present (Fig. 4.37).

Cystic changes mimicking aneurysmal bone cyst are occasionally encountered.

Occasionally encountered are foam cells, multinucleated giant cells, and myxoid changes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree