Introduction

Like the wrist, most patients with finger pathology are examined seated opposite the examiner. Interventional procedures can be carried out with the patient prone and their hand extended above their head if there is anxiety or fainting risk.

Position 1: Base of Thumb

Imaging Goals

- 1.

Identify the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint (STTJ) and the first carpometacarpal joint (CMCJ).

- 2.

Locate the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and aponeurosis of the first metacarpophalangeal joint (MCPJ).

Technique

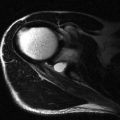

The basal joint of the thumb or the first CMCJ is best examined with the patient seated opposite and placing the ulnar aspect of their hand against the examination couch (karate chop position) ( Fig. 14.1 ). The probe is placed in the sagittal plane aligned along the long axis of the thumb. The first metacarpal is distinguished from the much shorter tripezium and, from this landmark, the CMCJ is easily found. The tripezium separates the CMCJ from the adjacent scaphoid and scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint in between. Degenerative changes in these two joints are a common cause of radial-side symptoms. Both are visualized from the sagittal probe position described above and can be injected together, or separately, as symptoms and ultrasound findings dictate.

The first MCPJ is reinforced by collateral ligaments medially and laterally and by a volar plate on the flexor side. Assessment of the UCL of the thumb is a commonly performed examination as this ligament is frequently injured. The injury will be dealt with in detail in a later section; however, the technique for identifying the ligament, its important relationships and the method for stressing the ligament will be covered here.

The UCL is best examined by asking the patient to place their hand palm downwards on the examination couch. For an examination of the right hand, the examiner sits opposite and places the probe in their left hand and takes the painful thumb in their right hand, raising the thumb and hand off the table slightly. The patient’s first proximal phalanx rests on the examiner’s middle finger in a position that allows the interphalangeal joint to be moved by the examiner’s thumb. The examiner’s index finger is placed on the ulnar side of the patient’s first metacarpal ( Fig. 14.2 ). In this position the examiner can use their thumb to gently flex the interphalangeal joint and can use their index finger and thumb combined to induce valgus stress in the UCL.

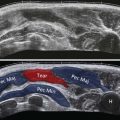

The imaging goals for patients with UCL injuries are: firstly, to determine if the ligament is torn and secondly, to detect displacement. The ligament is displaced if it lies proximal and superficial to the adductor aponeurosis that overlies it. To make this determination, the aponeurosis must be located first. Flexion of the interphalangeal joint moves the aponeurosis over the UCL. It is seen as a thin line with the ultrasound configuration of a ligament moving to the subcutaneous fat and overlying the UCL. It is usually relatively straightforward to identify whether the ligament lies deep to it or has been displaced proximally. Once a torn ligament and overlying aponeurosis have been detected, the extent of the injury can be classified. This is discussed in more detail on page 158, but simply put, if the ligament is disrupted but remains deep to the aponeurosis, the injury can be treated conservatively. If the ligament is disrupted and has been displaced (called a Stener lesion), surgery may be a preferential form of treatment.

Once the correct location of the ligament is confirmed, the next step is to gently stress it. Using the tip of the index finger in the position described above as a fulcrum, very gentle abduction stress is placed using the examiner’s thumb against the proximal phalanx. A small degree of joint opening is normal. This movement can be helpful in depicting the torn ligament end. Some advise against stressing the ligament because of the potential to displace the ligament significantly; however, this is very unlikely to occur with the usual degree of clinical stress used. The radial collateral ligament is easier to visualize as it lies on the radial aspect with no adjacent fingers to impede probe positioning.

Position 2: Flexor Aspect of Fingers

Imaging Goals

- 1.

Identify both flexor tendons.

- 2.

Identify the annular pulleys.

- 3.

Locate the volar plate and collateral ligaments.

Technique

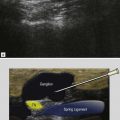

The paired flexor tendons run close together to the level of the proximal end of the middle phalanx ( Fig. 14.3 ). They are easy to separate in the palm up to the point that they enter the common tendon sheath just proximal to the metacarpal head. Distal to this they are often so close together that they may appear as a single tendon. By fixing the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) and moving the distal interphalangeal joint (DIPJ), the deeper profundus tendon moves in isolation and can be seen separately. Compressing with the probe also tends to move the two tendons separately due to their slightly different angle of curvature. Having said that, differentiating the tendons in this way is not particularly clinically important. At about the level of the middle of the proximal phalanx, the superficial tendon begins to divide into its two slips ( Fig. 14.4 ). These gradually separate and deviate away from each other and pass one medially and one laterally to the profundus tendon and to their insertions near the base of the middle phalanx. This anatomy is best observed by holding the probe in the axial plane and gradually tracking distally along the tendon. The profundus tendon then continues on its own to its insertion at the base of the distal phalanx.