CHAPTER 8 Fluoroscopic examinations of the pharynx, esophagus and stomach

Introduction

Roentgen’s first publication on the discovery of x-rays and the x-ray absorption characteristics of metals and salts was in 1895. The potential for fluoroscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract with contrast medium was raised immediately after Roentgen’s seminal paper. In 1896, the German physician Wolf Becher utilized Roentgen’s work to develop the concept of using contrast medium to provide an image of the stomach (Thomas, 1998).

Walter Bradford Cannon, a physiologist at Harvard University, studied digestion in animals using bismuth and x-rays. Using heavy metal salts mixed with food, Cannon studied gastrointestinal motility, tracing the fluoroscopic appearance of contrast through the alimentary tract. Changing from bismuth to barium in 1924, Cannon adapted the study for humans (Sebastian, 1999).

The barium swallow

The barium swallow is a simple, safe and effective examination for patients with symptoms of dysphagia. It can provide a significant amount of information both on its own or complementary to endoscopy or esophageal motility studies (Esfandyari et al., 2002; Hansmann and Grenacher, 2006).

The clinical indications for a barium swallow are high (pharyngeal) or low (esophageal/esophago-gastric) dysphagia, the root cause being either neuromuscular or mechanical. Common causes for high and low dysphagia are given in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Potential causes of dysphagia

| High (pharyngeal) dysphagia | Low (esophageal/gastro-esophageal) dysphagia |

|---|---|

CVA: cerebrovascular accident

The objective of the barium swallow is for the practitioner to:

Pharyngeal and esophageal swallow technique

Before commencement of formal imaging, the patient is given an initial swallow of barium, and its passage to the stomach is screened to check there is no mechanical obstruction. The patient is placed in the right anterior oblique or lateral position as this projects the esophagus away from the spine and trachea. In this position, there is a better chance of differentiating barium in the trachea originating from a tracheo-esophageal fistula from that which has been aspirated. Regardless of the cause of the barium in the trachea, the patient will cough if that reflex is present. Coughing will result in the barium coating the trachea which might subsequently make it difficult to determine the cause for the barium being present.

Imaging

As an optimal minimum, imaging patients with high dysphagia should include videofluoroscopy or rapid imaging sequences of the pharynx (e.g. at least 3–4 frames per second). Videofluoroscopic assessment of swallowing disorders is expored further in Chapter 7.

The pharynx is examined in the lateral, the left or right anterior oblique, and the anteroposterior projection. The alternate oblique need only be considered if an abnormality is suggested. If pharyngeal imaging options are limited, the lateral projection provides the greatest breadth of information and can demonstrate aspiration and pharyngeal abnormalities such as pharyngeal pouch, webs, pharyngeal neoplasm, prominence of the cricopharyngeus (Figures 8.1, 8.2, 8.3, 8.4 and 8.5) and osteophyte impression.

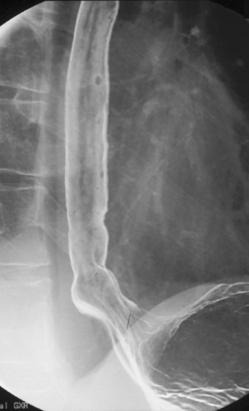

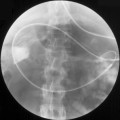

Imaging of the esophagus, esophago-gastric junction and gastric fundus must always be included whether symptoms suggest high or low dysphagia. Turning the patient towards the right anterior oblique position will demonstrate the esophagus away from the spine (Figures 8.6 and 8.7).

Demonstration of the esophagus can be achieved by asking the patient to drink the barium and keep swallowing as quickly as possible. Esophageal distension is maintained by the second swallow inhibiting the first and the third inhibiting the second etc. If the patient cannot cope with continuous swallowing, the alternative is to take a number of separate swallows, overlapping imaging of the distended esophagus.

The importance of obtaining full distenson of the esophagus cannot be emphasized enough as plaque lesions can be missed (Figure 8.8). If full distension is not considered to have been achieved the swallow must be repeated.

Separate images should be taken of the esophago-gastric junction (Figures 8.9, 8.10 and 8.11); the optimal degree of obliquity can be identified from the initial screened swallow. Additional images should be considered as appropriate if an abnormality is suggested.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree