CHAPTER 12 Fluoroscopic investigations of the small bowel

Introduction

When compared with the high technical standards expected of barium radiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract and the double contrast barium enema, small bowel imaging could be considered to be the poor relation. Maglinte et al. (1996) suggest that small bowel imaging has been ‘performed casually without attention to detail’, ‘for the sake of completeness’. That said, the strengths and weaknesses of barium examinations of the small bowel have all been thoroughly examined in the past and have stood the test of time. Although many of the papers on the subject were published in the 1990s, 1980s or even the 1970s, their conclusions are still relevant today.

Antes (2003) raised the concern that, with the decrease in frequency of barium examinations, ‘the art of performance and interpretation (of these examinations) might get lost’. The development of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) software has enabled cross-sectional imaging to establish a number of techniques to demonstrate the small bowel, but alternative modalities should only replace tried and tested techniques with caution.

Price and Le Masurier (2007) suggest that, in the UK, 80% of District General Hospitals now have radiographers performing barium fluoroscopy, predominantly the double contrast barium enema. Historically, small bowel radiology has been the province of radiologists, but Law et al. (2005) demonstrated that radiographer performance and reporting of small bowel enteroclysis (SBE) has a sensitivity and specificity comparable to published standards.

Unlike upper and lower GI tract investigations, the radiological approach to investigating the small bowel is not well defined and local preference and expediency is more closely involved in the equation to determine what is considered acceptable and best practice. Departments that routinely perform small bowel enteroclysis are still in the minority (Ha et al., 2004).

Bowel preparation

It is not necessary to have the right colon as clear as you might wish for a double contrast barium enema, although marked fecal residue in the ascending colon can inhibit the passage of barium through the distal small bowel and ileocecal valve. A degree of clearance might also enable gross pathology affecting the iliocecal valve or proximal colon to be identified (Law, 1983; Nolan and Traill, 1997).

Flocculation

To maintain barium in suspension, manufacturers provide the barium particles with a protective coating, maintaining them in a separate state from one another. Muco-proteins generated in the GI tract are absorbed by the barium particles and, if prolonged exposure occurs, the absorption breaks down the protective coating of the particles allowing them to clump together. This is known as flocculation.

In normal instances, there is a greater likelihood of flocculation occurring with the BaFT due to the slower transit of barium through the small bowel. Its occurrence is non-specific, but should flocculation occur during the more rapid transit of enteroclysis, there is a greater likelihood of flocculation being relevant to the diagnosis (Lomoschitz et al., 2003).

The per oral barium follow through (BaFT)

The BaFT examination is far more widely used to image the small bowel than enteroclysis. Toms et al. (2001) offered a number of reasons why the BaFT might be advocated:

Ha et al. (2004), in reviewing radiographic examinations of the small bowel and practice patterns in the USA, stated that the BaFT is the dominant small bowel examination in the USA. The main examination technique consists of over-couch radiographs (of the whole abdomen), which should be coupled with fluoroscopic spot images of the terminal ileum. However, the paper also states the BaFT technique advocated by the American College of Roentgenologists is fluoroscopy-dependent, with palpation of all accessible small bowel loops including the terminal ileum, with appropriate images to demonstrate any abnormality or representative images if no abnormality is demonstrated. The technique that is advocated can result in a more time-consuming examination. Maglinte et al. (1996) state that the BaFT as ‘conventionally performed has no place in the practice of cost effective medicine’. The use of the fluoroscopy-dependent BaFT technique is well supported (Maglinte et al., 1987, 1996; Ha et al., 2004).

The BaFT might be considered ‘safer’ and less invasive than the SBE and preferred by most patients as it does not require enteral intubation. Some practitioners consider the BaFT the examination of choice in known Crohn’s disease. In its simplest form, the least advocated BaFT technique requires minimal fluoroscopy room occupation and might thus be considered less labour intensive (Maglinte et al., 1987, 1996; Bernstein et al., 1997; Nolan and Traill, 1997; Toms et al., 2001).

Barium follow through technique

A considered barium solution might comprise 300 ml Baritop 100 (Sanochemia UK), diluted with 400 ml water (75%w/v), 10 ml Gastrografin and 6 sachets of Carbex granules. The combined use of the hyperosmolar Gastrografin and the effervescent agent Carbex can significantly reduce small bowel transit time without affecting the examination quality (Summers et al., 2007); 600 ml of solution is ingested in as short a time as the patient finds comfortable.

Once barium is in the colon, relaxing the bowel muscle by using an intravenous hypotonic agent has been reported as being of value (Bernstein et al., 1997). Focal images are taken of the terminal ileum and any identified abnormality as well as fluoroscopic or over-couch images taken to demonstrate an overview of the whole small bowel (Box 12.1).

BOX 12.1 Single contrast barium follow through technique

A solution of 300 ml of 100% barium (Baritop 100), 400 ml of water, 10 ml Gastrografin and 6 sachets of Carbex granules (23% w/v)

A solution of 300 ml of 100% barium (Baritop 100), 400 ml of water, 10 ml Gastrografin and 6 sachets of Carbex granules (23% w/v) If barium appears to be delayed, it may be due to air trapped within the small bowel; in these instances, it is worth considering intermittently turning the patient into the prone position to aid onward passage

If barium appears to be delayed, it may be due to air trapped within the small bowel; in these instances, it is worth considering intermittently turning the patient into the prone position to aid onward passage Injection of an IV hypotonic agent (1 mg in 1 ml Buscopan or 10 mg in 1 ml glucagon) will halt peristalsis when barium reaches the colon

Injection of an IV hypotonic agent (1 mg in 1 ml Buscopan or 10 mg in 1 ml glucagon) will halt peristalsis when barium reaches the colonLimitations of the barium follow through

Nolan and Traill (1997) and Toms et al. (2001) suggest that because of the nature of the technique, a higher number of BaFT examinations require further investigation to confirm normality or otherwise. Good distension is not usually achieved therefore early strictures, subtle appearances and fine nodules are more likely to be missed.

Maglinte et al. (1987, 1996) report that the sensitivity and specificity of the BaFT is technique and operator dependent, although Maglinte et al. (1982) refer to diagnostic errors being more of a technical nature than perceptual.

Small bowel enema or enteroclysis (SBE)

The word enteroclysis derives from the Greek words ‘enteron’ meaning ‘intestine’ and ‘klysis’ meaning ‘a high enema’. Its use in the context of this examination is of uncertain origin but might be to disassociate from the word enema and the perception that rectal intubation will be required.

Despite advances in other imaging techniques and the limited popularity of small bowel enteroclysis, the SBE is widely accepted as currently being the optimum technique for examining the small bowel. The SBE is also commonly used as the reference point for other small bowel imaging methods (Maglinte et al., 1987, 1992; Nolan and Traill, 1997; Nolan, 1997; Antes, 2003).

The techniques of performing small bowel enteroclysis have evolved over 80 years. Pesquera (1929) published a technique using duodenal intubation as a means of infusing a barium, acacia and water mixture that enabled the demonstration of the whole small bowel. Sellink (1976) mentions Gershon-Cohen and Shay (1939), Scott-Harden et al. (1961) and Bilbao et al. (1967) who, among others, over the intervening years, advanced the development of techniques to examine the small bowel. In the 1970s, single contrast enteroclysis re-emerged, gaining popularity through the distillation of ideas and publications of advocates such as Sellink (1974) who consider the mitigating features of the SBE outweigh the arguments that are put forward against its use.

The patient experience

Principle of the single contrast SBE technique

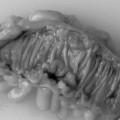

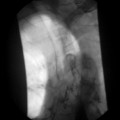

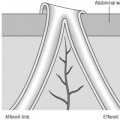

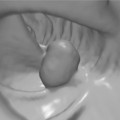

A low density barium suspension of around 20%w/v (such as 300 ml Baritop 100 diluted with 1500 ml water) is infused through the tube at a rate that allows a single column of barium to distend and pass through the small bowel to the colon (Figure 12.1).

Barium transit to the colon is reported as often being less than 35 minutes.

Optimum results are best achieved by: