CHAPTER 11 Fluoroscopically guided fine bore intubation

Background

The UK National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) has reported that approximately 500 000 fine bore feeding tubes are distributed annually within the National Health Service (NPSA, 2005). The vast majority of nasogastric intubations are uncomplicated and dealt with by suitably trained practitioners within the ward environment. Patients requiring fine bore intubation for nutritional support are by virtue of the requirement to be intubated, unwell and vulnerable to complications from misplaced intubations or the distress of repeated attempts.

The NPSA reported that they were aware of 11 deaths between 2002 and 2004 resulting from misplaced nasogastric (NG) tubes and, since that time, the NPSA Patient Safety Bulletin has reported a further five deaths and four near misses from misplaced nasogastric tubes (NPSA 2005, 2007).

Accurate information is sparse as to the nature and number of complications associated with fine bore intubation; however, from the serious complications reported to the NPSA, misreading of x-ray checks is a significant factor and it is suggested that interpretation of these images must be carried out by practitioners trained to report them (NPSA, 2005).

Checking intubation siting

There are numerous tests to check the position of the tube tip. Some, such as auscultation or the use of blue litmus paper to test acidity/alkalinity, have been discredited (NPSA, 2005).

In the ward environment, the measurement of the pH of gastric aspirate is currently considered the safest and easiest repeatable means of confirming the siting of a fine bore tube in the stomach. However, gastric pH can be above 5.5 in a number of circumstances, falsely suggesting that the tube might not be in the stomach, for example in patients taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), patients who have pernicious anemia, or who have had a recent fluid intake. The type of fluid, feeding formulae or medication is also relevant (Stroud et al., 2003; Bain, 2005).

Endoscopy can be used to insert fine bore tubes when blind intubation on the ward has failed, although local anesthesia to the pharynx and sedation may be required; additionally, the tube can be dragged back upon removal of the endoscope. In normal circumstances, endoscopically guided fine bore tube insertion could be considered excessive. Diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy has associated complications. Quine and Bell (1995) indicated a mortality and morbidity in the region of 1:12 000 and 1:230 respectively and, more recently, the British Society of Gastroenterology figures reported by Teague (2003) suggested little change.

In discussing the thoracic and non-thoracic complications of gastric and enteric intubation, Pillai et al. (2005) refer to the radiographic check of tube placement as continuing to be the ‘gold standard’.

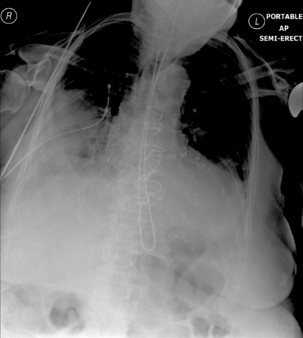

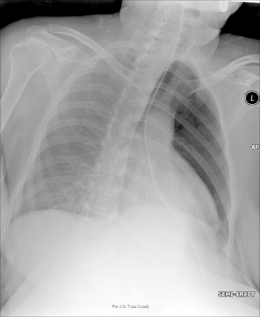

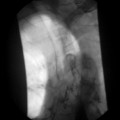

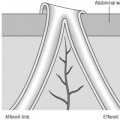

Radiography provides a snapshot of the fine bore tube position at the time of the x-ray, accurately identifying the site of misplaced tube tips (Figures 11.1, 11.2, 11.3 and 11.4).

Figure 11.3 Tube tip passed via right bronchus penetrating the pleural cavity – associated pneumothorax.

However, inexperience in image interpretation can lead to the misreading of tube siting. The benefits of fluoroscopy are shown in a case where misinterpretation of chest radiographs on an unconscious patient in a high dependency unit led to a number of failed blind and endoscopic intubations. The tube was considered repeatedly to be sited in the right side of the chest (Figure 11.5). Fluoroscopic tube guidance and the careful infusion of a water-soluble contrast medium demonstrated a redundant loop of colon and a strictured cologastric anastomosis. The appearance is of a late onset complication from a previous colonic interposition for esophageal atresia of which the clinical team were unaware (Figure 11.6) (Law, 2006).

Radiographer and radiologic technologist involvement

Price and Le Masurier (2007) suggest that 80% of District General Hospitals in the UK have radiographers performing DCBE examinations. Radiography provides an accurate snapshot of the fine bore tube position at the time of the x-ray. As long as the tube is radiopaque, a skilled practitioner can provide accurate information as to whether the tube is in the stomach or not. However, this raises the question of what should happen when an x-ray shows the tube is not correctly placed: should patients return to wards for tube resiting?

Radiographers skilled in GI fluoroscopy are ideally positioned to provide an intubation service and can quickly and easily acquire expertise in nasogastric/enteric intubation. With the wide potential for gaining experience, radiographers may well succeed with nasogastric intubating without recourse to fluoroscopy even if blind intubation on the ward has been unsuccessful.

For correctly positioned tubes:

The role of the clinical radiographer might include:

Fluoroscopically guided intubation of nasoenteric fine bore tubes is a safe and effective technique (Prager et al., 1986; Law, 1990). A core team of radiographers or radiologic technologists skilled in GI fluoroscopy developing expertise in siting problematic fine bore tubes, have the potential to offer major positive changes regarding intubation and to offer the development of a more flexible service.

Tube wire requirements

Fundamental to any intubation, problematic or otherwise, is the design of the fine bore (FB) tube (Law and Longstaff, 1992). The following features should be considered when selecting an FB tube (Box 11.1):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree