Anatomy, embryology, pathophysiology

The uterus is a thick-walled muscular organ of the female reproductive system that lies in the true pelvis posterior to the bladder and anterior to the rectosigmoid colon. It is divided into the body (corpus) and cervix at the internal os, and it consists of an inner mucosa (endometrium), a middle muscular layer (myometrium), and an outer serosa (perimetrium). The endometrium and the inner one-third of the myometrium, known as the junctional zone, are of Müllerian origin, while the outer myometrium has a non-Müllerian mesenchymal origin. Focal uterine lesions originate from these layers and can be categorized into two groups:

- ◼

Benign

- ◼

Uterine leiomyomas (uterine fibroid): most common solid benign uterine lesion, occurs in 20% to 30% of women, increased prevalence and rate of growth in African-American women, monoclonal proliferation of smooth muscle cells with various amounts of fibrous connective tissue, commonly multiple (85%), based on their location ( Fig. 32.1 ):

- ◼

Intrauterine:

- ◼

Intramural: most common, centered primarily within the myometrium.

- ◼

Subserosal: nearly more than 50% of the fibroid protrudes out of the serosal surface of the uterus.

- ◼

Submucosal: least common, a common source of abnormal uterine bleeding, may also present with reproductive dysfunction (recurrent miscarriages, infertility, premature labor, and fetal malpresentation).

- ◼

- ◼

Extrauterine:

- ◼

Broad ligament leiomyoma: Arises from the smooth muscle elements of the broad ligament, also referred to as a type of parasitic leiomyoma.

- ◼

Cervical leiomyoma: rare (0.6%–10%), clinical symptoms can be identical to those of leiomyomas in the uterine body.

- ◼

Parasitic leiomyoma: presents as a peritoneal pelvic benign smooth-muscle mass, likely originates as a pedunculated subserosal leiomyoma losing its contact with the uterus after twisting around its pedicle.

- ◼

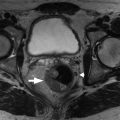

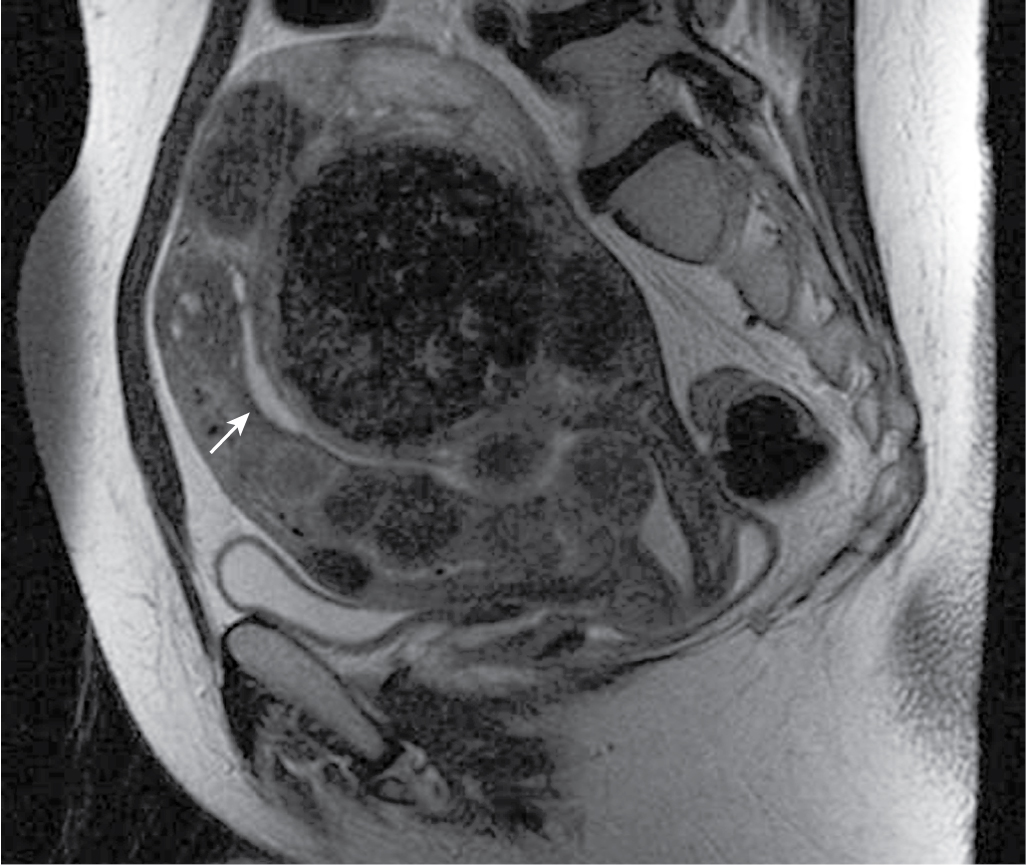

Fig. 32.1

Classification of fibroids on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Despite the presence of numerous fibroids that distort the endometrial canal, the location of the fibroids relative to the T2-hyperintense endometrium ( arrow ) can be readily assessed on MRI. Accurately characterizing fibroids as submucosal, intramural, or subserosal has implications for management.

(From Zagoria RJ, Brady CM, Dyer R.B. Genitourinary Imaging: the Requisites , ed 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.)

- ◼

- ◼

Lipoleiomyoma: rare lesion (0.03%–0.20%), fatty degeneration of smooth muscle cells in an ordinary leiomyoma, typically in a postmenopausal patient ( Figs. 32.2 and 32.3 ).

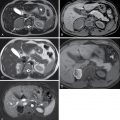

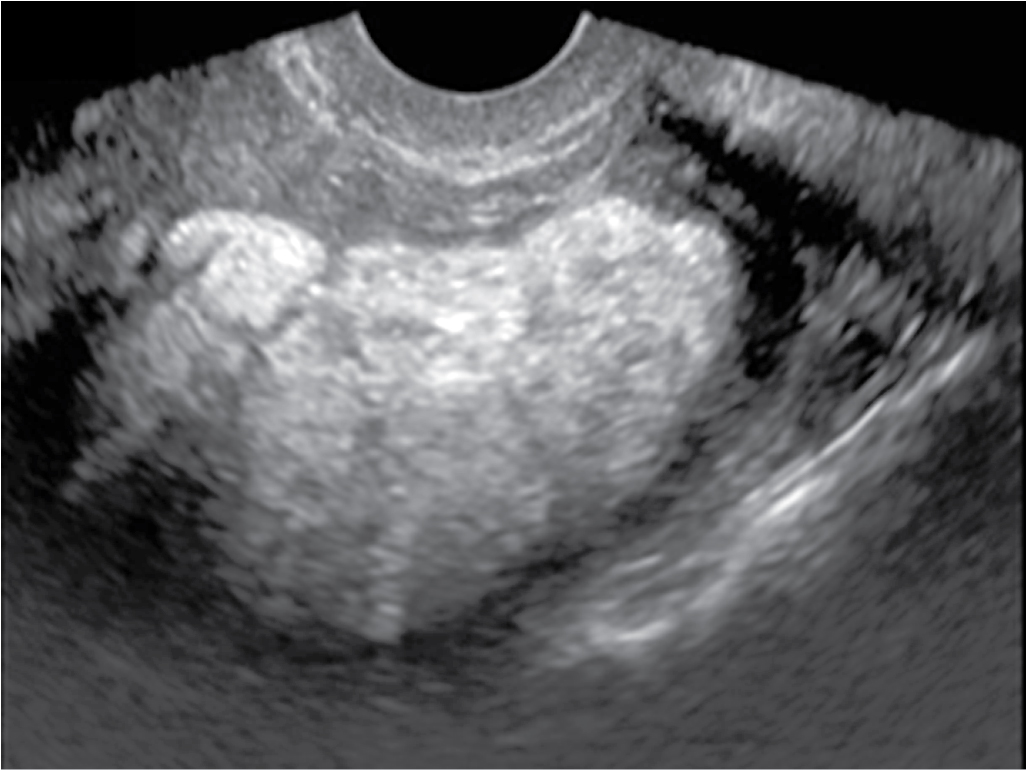

Fig. 32.2

Lipoleiomyoma. Longitudinal ultrasound image of the lower uterine segment shows a large, uniformly hyperechoic, nonshadowing mass, characteristic of fatty degeneration of a uterine fibroid.

(From Zagoria RJ, Brady CM, Dyer RB. Genitourinary Imaging: the Requisites , ed 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.)

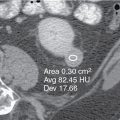

Fig. 32.3

Lipoleiomyoma on magnetic resonance imaging. A, On a coronal T1-weighted image, a large uterine mass is hyperintense relative to myometrium and similar in signal intensity to fat. B, This mass is markedly hypointense on a T2-weighted image with fat suppression, confirming the diagnosis of fatty degeneration of a uterine fibroid (lipoleiomyoma).

(From Zagoria RJ, Brady CM, Dyer RB. Genitourinary Imaging: the Requisites , ed 3. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.)

- ◼

Nabothian cyst: also known as retention cysts of the cervical glands, common, may be seen in up to 12% of routine pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, thought to form as a result of the healing process of chronic cervicitis.

- ◼

Hematometra: uterus distended with blood secondary to obstruction or atresia of the lower reproductive tract.

- ◼

Endometrial polyp: benign nodular protrusions of the endometrial surface, can be sessile or pedunculated, prevalence increases with age, frequently seen in patients receiving tamoxifen, consists of dense fibrous or smooth muscle tissue, thick-walled vessels, and endometrial glands.

- ◼

Endometrial hyperplasia: hyperplasia with increased gland-to-stroma ratio, usually presents as a homogeneous smooth increase in endometrial thickness but may also present as asymmetric/focal thickening with surface irregularity.

- ◼

Hemato-/hydrocolpos: a fluid-filled dilated vagina because of an anatomic obstruction, such as imperforate hymen (most common), vaginal stenosis or transverse vaginal septum.

- ◼

Transient uterine contraction: a physiologic phenomenon that may mimic focal adenomyosis.

- ◼

Uterine adenomyoma: a focal region of adenomyosis resulting in a mass, difficult to distinguish from a uterine fibroid, most commonly occurs at the fundal endometrial-myometrial interface.

- ◼

Early pregnancy.

- ◼

Molar pregnancy (Hydatidiform mole): a common complication of gestation, estimated to occur in one of every 1000 to 2000 pregnancies:

- ◼

Complete mole: 90% are diploid (46XX), egg with no chromosome + single sperm (less commonly two sperms), absence of a fetus.

- ◼

Partial mole: usually triploid (69XXY), normal egg + two sperms, an abnormal fetus or even fetal demise.

- ◼

- ◼

- ◼

Malignant:

- ◼

Cervical carcinoma: thought to arise from the transformation of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), histologic subtypes:

- ◼

Squamous cell carcinoma (80%–90%): associated with exposure to human papillomavirus (HPV).

- ◼

Adenocarcinoma (5%–20%):

- ◼

Clear cell carcinoma.

- ◼

Endometrioid carcinoma: around 7% of adenocarcinomas.

- ◼

Mucinous carcinoma: such as adenoma malignum, which represents around 3% of adenocarcinomas.

- ◼

Serous carcinoma.

- ◼

Mesonephric carcinoma: around 3% of adenocarcinomas.

- ◼

Neuroendocrine tumors: such as small cell carcinoma 0.5% to 6%.

- ◼

- ◼

Adenosquamous cell carcinoma: rare.

- ◼

- ◼

Endometrial carcinoma

- ◼

Type I (80%): unopposed hyperestrogenism and endometrial hyperplasia, 55 to 65 years old, well differentiated tumors with relatively slow progression, most common histologic subtype is endometrioid carcinoma (85%).

- ◼

Type II (20%): endometrial atrophy, 65 to 75 years old, less differentiated and spreads early via lymphatics or through Fallopian tubes into peritoneum, histologic subtypes:

- ◼

Papillary serous carcinoma (5%–10%).

- ◼

Clear cell carcinoma (1%–5.5%).

- ◼

Adenosquamous carcinoma (2%).

- ◼

Adenocarcinoma with squamous differentiation (0.25%–0.50%).

- ◼

Undifferentiated carcinoma.

- ◼

- ◼

- ◼

Uterine sarcoma (1%–6%): composed of part or all mesodermal elements.

- ◼

Pure.

- ◼

Leiomyosarcoma (33%–50%): malignant, women in the sixth decade, mostly arise from uterine musculature or the connective tissue of uterine blood vessels, preexisting leiomyoma can also rarely go through sarcomatous transformation.

- ◼

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (10%).

- ◼

Fibrosarcoma (rare).

- ◼

Rhabdomyosarcoma (rare).

- ◼

Liposarcoma (rare).

- ◼

Angiosarcoma (rare).

- ◼

- ◼

Mixed.

- ◼

Malignant mixed Müllerian tumor (50%–70%): uterine carcinosarcoma, 2% to 8% of all malignant uterine cancers, highly aggressive tumor.

- ◼

Mixed uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma.

- ◼

- ◼

- ◼

Techniques

Pelvic ultrasonography

- ◼

Initial study of choice for workup.

- ◼

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) offers higher-resolution imaging and is the initial imaging study of choice.

- ◼

Limited by:

- ◼

Small field of view (FOV).

- ◼

Obscuration of organs by overlying bowel gas.

- ◼

Operator dependence.

- ◼

Patient-related factors: body habitus, and distorted anatomy secondary to large and/or multiple fibroids.

- ◼

- ◼

Performing a transabdominal ultrasound (US), in addition to TVS can be helpful in evaluating specific uterine lesions.

- ◼

Color and duplex Doppler US allow for the assessment of uterine and endometrial vascularization and may be of added value in further characterizing an endometrial abnormality detected at US.

- ◼

Sonohysterography can also improve diagnostic performance of US for specific lesions.

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

Outperforms US with higher specificity because of its multiplanar imaging capabilities and excellent soft-tissue contrast for tissue characterization.

- ◼

Excellent method for imaging evaluation when US is not feasible or the findings at US are inconclusive.

- ◼

Most valuable for evaluating extent of disease and staging in patients with known or clinically suspected gynecologic malignancy.

- ◼

Perfusion and diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) sequences increase the diagnostic accuracy of conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- ◼

Dynamic contrast enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) using postprocessing subtraction techniques showing early enhancement in solid elements points toward malignancy, while absence of enhancing solid elements is more likely benign.

- ◼

Susceptibility-weighted imaging has a higher sensitivity for diagnosis of extraovarian endometriosis and adenomyosis.

- ◼

Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) measurements on DWI can help in differentiating fibroids from adenomyosis.

- ◼

Three-dimensional (3D) T2-weighted MRI allows volumetric acquisition providing submillimeter sections with multiplanar reformatting capability, with a tradeoff between acquisition time and T2-weighting characteristics.

Computed tomography

- ◼

Not recommended as a first-line test:

- ◼

Low sensitivity and specificity.

- ◼

Effects of ionizing radiation on the reproductive organs.

- ◼

- ◼

Commonly performed in patients with acute symptoms.

- ◼

Used mainly in staging carcinoma.

- ◼

Enhancement patterns of the uterus at computed tomography (CT) are dynamic and versatile, depending on several factors, such as age, menstrual status and acquisition phase.

- ◼

In the presence of morphologic alterations or atypical contrast enhancement of the uterus at CT, a directed study by ultrasound or MRI should be suggested.

Protocols

Protocol considerations

Transvaginal ultrasound

- ◼

Preferred over transabdominal US, unless:

- ◼

In infants, children, and adolescents.

- ◼

Patient preference.

- ◼

Visualization of the uterus at TVS is compromised by large myomas, a high position and fixation because of adhesions, or postpartum enlargement.

- ◼

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

A multicoil array allows for smaller FOV and higher spatial resolution.

- ◼

The patient should fast for 6 hours before the study to minimize bowel peristalsis.

- ◼

Glucagon can also be administered subcutaneously or intramuscularly.

- ◼

- ◼

T2-weighted images are most informative.

- ◼

Fast spin echo (FSE), turbo spin echo (TSE), or their equivalents are recommended in the orthogonal planes.

- ◼

Ultrafast T2-weighted pulse sequences, such as single-shot FSE or half-acquisition TSE may be used to save time at the cost of mildly diminished spatial resolution.

- ◼

Anterior saturation bands over the anterior subcutaneous fat help minimize phase-encoding artifacts.

- ◼

Contrast enhancement is essential for detecting tumor extent.

- ◼

Rapid T1-weighted gradient echo images should be obtained pre- and postdynamic intravenous bolus administration of a gadolinium chelate contrast material to identify disease locations.

- ◼

Arterial and venous phase images can be useful in determining the vascular supply and enhancement pattern of a pelvic mass.

- ◼

DWI with ADC map can also be helpful is evaluating the extent of disease.

Suggested protocols

Ultrasound

- ◼

Transabdominal:

- ◼

Patient in the supine position with a full bladder and the abdomen exposed. Slight flexion of the hips and knees helps to relax the abdominal muscles.

- ◼

Low frequency (2–5 MHz) curvilinear or phased array transducer.

- ◼

- ◼

Transvaginal:

- ◼

Patient in a lithotomy position or a reclined butterfly with an empty bladder and the hips elevated.

- ◼

Mid-frequency (5–8 MHz) endocavitary transducer.

- ◼

Place standard scanning gel on the probe for coupling followed by a transducer cover.

- ◼

Ensure that all air is expelled between the probe head and the transducer cover.

- ◼

Next, place bacteriostatic gel over the cover for lubrication.

- ◼

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ◼

Orthogonal high resolution T2-weighted FSE or a 3D T2-weighted volumetric acquisition.

- ◼

Axial in-phase, opposed-phase and/or fat-suppressed T1-weighted gradient echo.

- ◼

Long- or short-axis precontrast and dynamic postcontrast 2D T1-weighted or 3D T1-weighted acquisition (with fat suppression).

- ◼

Pre- and dynamic postcontrast fat-suppressed 3D T1-weighted gradient echo.

- ◼

DWI with ADC map.

Specific disease processes

Cervical carcinoma

- ◼

Radiographically visible: must be at least stage Ib or above.

- ◼

MRI is the imaging modality of choice.

- ◼

Evaluating the primary tumor and local extent.

- ◼

- ◼

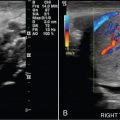

CT or positron emission tomography (PET) are used for assessing distant metastatic disease ( Fig. 32.4 ).